On Ma, the new album by folk-globalist Devendra Banhart, there are appearances by singer-songwriter Cate Le Bon and 1970s English folk-rock cult heroine Vashti Bunyan. Lyrics reference his love for Brazilian stars Chico Barque and Caetano Veloso as well as Japanese electro-art-pop pioneer Haruomi Hosono. And no less than Carole King is a presence in a co-write nod via lyrics drawn from “So Far Away.”

But when it comes to guest stars on the album, there’s one that’s hard to top: the Pacific Ocean.

Yup. That noted body of water is credited, fittingly, for “ocean sounds” on the song “October 12.” It’s a song of grief after the death of a friend, and Banhart, who spent much of his youth in Venezuela, his mother’s native country, sings it in Spanish.

“Actually, on every track there is the ocean,” he says, freshly landed at home in Los Angeles after flying across that very ocean from Singapore. “You don’t really hear it, but it is throughout the whole record. What inspired us to do that in the beginning, we recorded in a Buddhist temple in Kyoto with no walls. It is open to a garden. We wanted to create that feel on the album.”

Working with his longtime producer Noah Georgeson and several of his regular musical cohorts, Banhart was invited to record in that temple for just one hour, after a brief Asian tour. The experience was something they wanted to extend through the whole of the album, which they later accomplished by recording in a studio in a house along the Northern California coastline.

“You could hear the Pacific,” he says. “We had the windows open. That’s the big support system for the songs.”

It’s a nurturing presence, even in its most subtle ambience, it being the primal source of life. And as such, it represents the life-giving concept at the heart of the album: motherhood.

“Maternity is the theme,” he says.

There’s more than that here, of course. There is grief in songs such as “Memorial,” about his father, with temple bells mixed in the music, and “The Lost Coast,” about death and loss. The magic of serendipity permeates the album, as does the state of being open to what the world offers. None of the songs are explicitly about motherhood, per se. The notion, in many poetic manifestations, ties it together.

“There’s the relationship one has with a country,” he says, distressed about devastating political and economic strife of the nation in which he was nurtured. “Venezuela has been a constant issue on this record. Moments before now I was talking with my family and reading about what is going on there. It’s a truly apocalyptic situation. My way of writing about it is so related to my mother. At this point I can’t separate my own mother from Venezuela.”

His mother is not currently living there and the last time he visited was two years ago, but he has aunts and uncles and cousins who are there, seeing their country and its people suffer greatly. For him, it’s hard to separate that situation, with which he has such a deep personal relationship, from suffering elsewhere, whether from his own roots or in places where he has spent considerable time (Nepal and Tibet, among them) or that he has merely seen on the news.

“There is the insane suffering of the Venezuelan people, the political madness of the situation in the U.S., Duterte in the Philippines, China and Tibet suffering so much, and the people in Hong Kong.” Banhart seeks solace in the connections he’s made through music, “There’s music and art as the parent-and-child relationship. I turn to music to be consoled, to be less alone, to feel loved and nurtured.”

In that regard, few are more significant to him than Vashti Bunyan. The English singer came from the same folk-rock scene that gave us Fairport Convention, Nick Drake, and the Incredible String Band. Her 1970 album, Just Another Diamond Day, languished in obscurity until the late 1990s when it was “discovered” by musicians in a nascent movement that came to be called freak-folk, a young Banhart among its numbers. That brought about the album’s reissue, and various new recording projects, some involving Banhart. Now in her mid-70s, Bunyan sings with him here on the album’s closing “Will I See You Tonight?”

“Within that maternal theme, I don’t think anyone in my life encapsulates the archetype of the wisdom of artists as much as Vashti does, in terms of that nurturing quality of music,” he admits.

Banhart also seeks to make, or embrace, connections in music itself, some coming quite by surprise. This album is threaded with inspirations from and references to music from many lands and cultures, often connecting in ways wondrous, delightful, and serendipitous. Rarely is any of that planned — at least consciously.

“Sometimes the lyrics come first,” he says. “The music is a platform for the lyrics. As you start, as the song starts to take shape, there’s some collaborative element with other musicians, but also with the song itself, in that way. I don’t mean to be oblique, but it’s this strange way that it takes you in these certain directions. It’s out of your hands.

Sometimes it’s easy, he says, as in the song “Carolina,” which cites an earlier song that has influenced him.

“It’s a song for a song, a song written for the song ‘Carolina’ by Chico Barque,” he says. “It’s an homage to Brazilian music and South American music. There’s a samba feel to it, and me really singing about wanting to hear that song and saying I should probably learn Portuguese someday. In those lyrics it was easy to see the shape of that music.”

Others have more convoluted paths, but in them reveal the global pathways he has so openly relished in his music and in his life.

“In some songs I was quite surprised what was coming out.”

“Kantori Ongaku” offered several such surprises. In the chorus, sung in Japanese, he uses words from a song by Hosono, one of the founders of Japan’s landmark trio Yellow Magic Orchestra. At one point in the cited lyrics, Hosono sings, in English, the words “country music.” That planted some ideas for Banhart as he wrote his song although he wished to sidestep literalism.

“I wanted to do a Buck Owens thing here but that wouldn’t work out,” he says. “J.J. Cale was a great hero of mine so I took J.J. Cale as inspiration, not literally, but that kind of platform emerged for the song. Those things aren’t really done consciously. There are people who are inspirations I’ve been listening to for so long that it enters into the music, naturally.”

In some ways, Ma is a culmination of Banhart’s past work in a career from the two shambling albums he released in 2002 through 2016’s ambling Ape in Pink Marble that’s seen him go from neo-hippie troubadour to bossa nova evangelist, from playful folkiness to, well, playful electro-pop. He’s been a part of collaborations with kindred spirits from Beck to Brazilian tropicalia great Gilberto Gil, with whom he shared the Hollywood Bowl stage one highly memorable evening, to the Strokes’ Fabrizio Moretti to Antony and the Johnsons.

Yet the range and depth of Ma extends beyond even that, particularly in its emotions, the sense of loss in some songs not just complementing the joy in others, but expanding upon it in ways that truly honor the maternal wonder of the world.

How to make that work? How to bring all that together so naturally?

Well, now we get to the other concept of Ma. Yes, the title is a word generally associated with mothers. Banhart’s use of it comes from something else.

“The word ma is actually born from a different meaning,” he says. “It’s a philosophical term for space in Japanese. Starting the record in Kyoto, that’s where I learned the word. I’ve always failed but have strived to get a type of space in the music. How do you create spaciousness in music? Ma is a term of how essential it is to an object, and in music the space between the notes is essential. I really got into that word, and it also happened to be the perfect word for the theme of the album.”

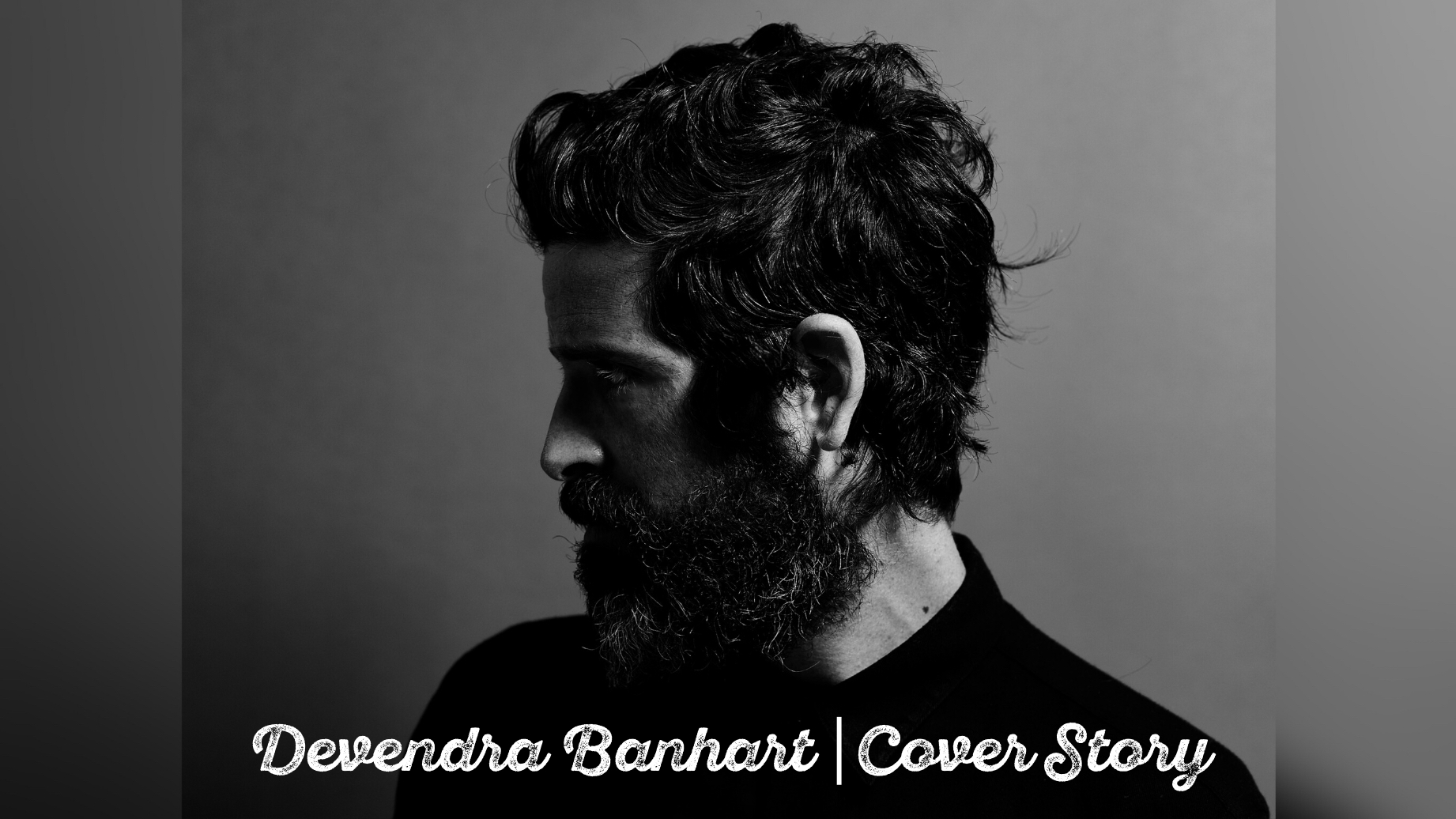

Photo Credit: Lauren Dukoff