Tag: Charlie Parr

The BGS Radio Hour – Episode 215

Welcome to the BGS Radio Hour! Since 2017, this weekly radio show and podcast has been a recap of all the great music, new and old, featured on the digital pages of BGS. This week, the Radio Hour features a song that reclaims the image of the magnolia tree, we enjoy some blues and southern rock from folks like Charlie Parr, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, and Larkin Poe, plus hear a “Wichita Lineman” cover by Colin Hay, and much more.

Gregory Alan Isakov – “Salt And The Sea”

To celebrate the birthday of Dualtone Music Group, Gregory Alan Isakov covers The Lumineers’ “Salt And The Sea” on a new compilation record, Amerikinda: 20 Years of Dualtone, which features many of Dualtone’s artists from the past and the present performing each other’s songs in a whimsical, jovial tribute to the work and achievements of this beloved record company.

Adia Victoria – “Magnolia Blues”

On a new track inspired by the last year and its intentional pausing, Adia Victoria explores the magnolia as a symbol of the South: “The magnolia has stood as an integral symbol of Southern myth making, romanticism, the Lost Cause of the Confederates and the white washing of Southern memory. ‘Magnolia Blues’ is a reclaiming of the magnolia…”

One of the most eloquent tracks on Jim Lauderdale’s new album Hope — a collection reminiscent of dreamy ‘70s folk rock records — celebrates the legendary Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, a longtime friend and collaborator of Lauderdale’s who died in 2019. As one of the final songs they wrote together, “Memory” arrived on June 22, just one day before what would’ve been Hunter’s 80th birthday.

We caught up with singer-songwriter Carrie Newcomer for a 5+5 — that’s five questions and five songs — on growing up creative, writing stories, poetry, and essays, taking comfort in nature and its imagery, and more.

Larkin Poe & Nu Deco Ensemble – “Every Bird That Flies”

Larkin Poe grew up drawing inspiration from a wide range of genres, so they always dreamt of honoring their classical upbringing with orchestral arrangements of their music. Their first ever live album features Nu Deco Ensemble combining those classical elements with Larkin Poe’s Americana, blues, and Southern rock songs.”In hearing our Roots Rock ‘n’ Roll repertoire reinterpreted through an orchestral lens, it felt like a creative circle was being completed.”

Christone “Kingfish” Ingram seemed to come out of nowhere with his 2019 Alligator Records debut, Kingfish. At 20 years old, the native of Clarksdale, Mississippi, emerged as a fully-formed guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter and was quickly hailed as a defining blues voice of his generation. Now his new record, 662, pays tribute to his upbringing and his home turf.

Jesse Lynn Madera has written a lot of sad, emotional songs, but writing “Revel” changed the way she approaches songwriting, recognizing the opportunity artists have to positively impact a person. She reflects, “Being human is rollercoaster enough without a pandemic to further complicate the experience. We’ve all suffered through our share, and hopefully we’ve all experienced the sun coming up over the horizon of despair. This will be no exception. The glow shall return, and we’ll all be reveling in it.”

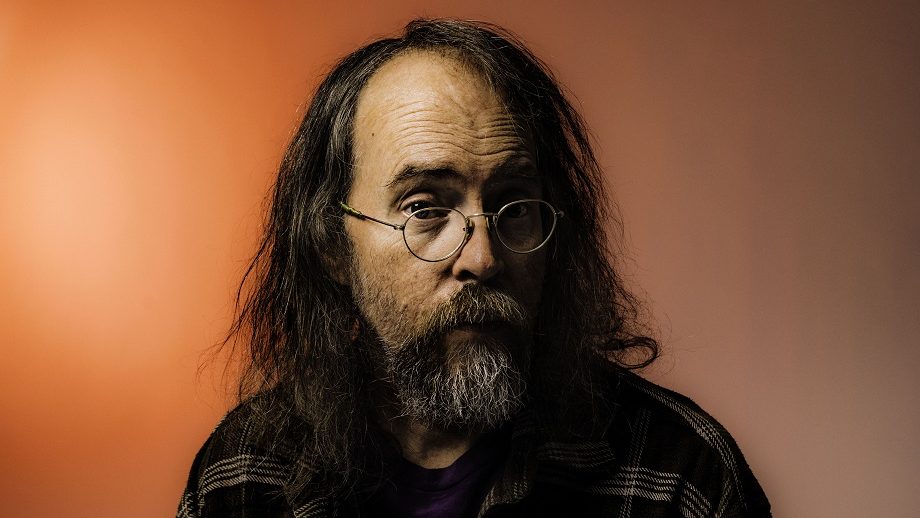

Charlie Parr – “Last of the Better Days Ahead”

Blues picker Charlie Parr reflects on the days he’s currently living in on “Last of the Better Days Ahead.” As he tells us: “I’m getting on in years, experiencing a shift in perspective that was once described by my mom as ‘a time when we turn from gazing into the future to gazing back at the past…'”

“Wichita Lineman” was the first song where Colin Hay (of Men at Work) realized the importance of the written song, in and of itself. He tells us the song “spoke of things I could only wonder at. The geographical vastness of the land, the hopes and dreams of the man working the line, and indeed of all people who inhabit this country. And, a love story contained within achingly beautiful music and melody. I can’t think of a better song.”

For a big part of their life, Dillbilly grew up feeling like country and bluegrass were genres that they could never be a part of even though the music has always felt like home. But in writing “Countries,” it felt so good for them to lean into those roots.

The Isaacs – “Turn, Turn, Turn”

Powerhouse bluegrass (and beyond) family The Isaacs have returned with new music, including their rendition of a Pete Seeger classic that Lily Isaacs recalls from her days of growing up as a folk music fan in 1960s New York City.

Photos: (L to R) Larkin Poe by Josh Kranich; Charlie Parr by Shelly Mosman; Adia Victoria by Huy Nguyen

WATCH: Charlie Parr, “Last of the Better Days Ahead”

Artist: Charlie Parr

Hometown: Duluth, Minnesota

Song: “Last of the Better Days Ahead”

Album: Last of the Better Days Ahead

Release Date: July 30, 2021

Label: Smithsonian Folkways

In Their Words: “Last of the Better Days Ahead is a way for me to refer to the times I’m living in. I’m getting on in years, experiencing a shift in perspective that was once described by my mom as ‘a time when we turn from gazing into the future to gazing back at the past, as if we’re adrift in the current, slowly turning around.’ Some songs came from meditations on the fact that the portion of our brain devoted to memory is also the portion responsible for imagination, and what that entails for the collected experiences that we refer to as our lives. Other songs are cultivated primarily from the imagination, but also contain memories of what may be a real landscape, or at least one inspired by vivid dreaming.” — Charlie Parr

Photo credit: Shelly Mosman

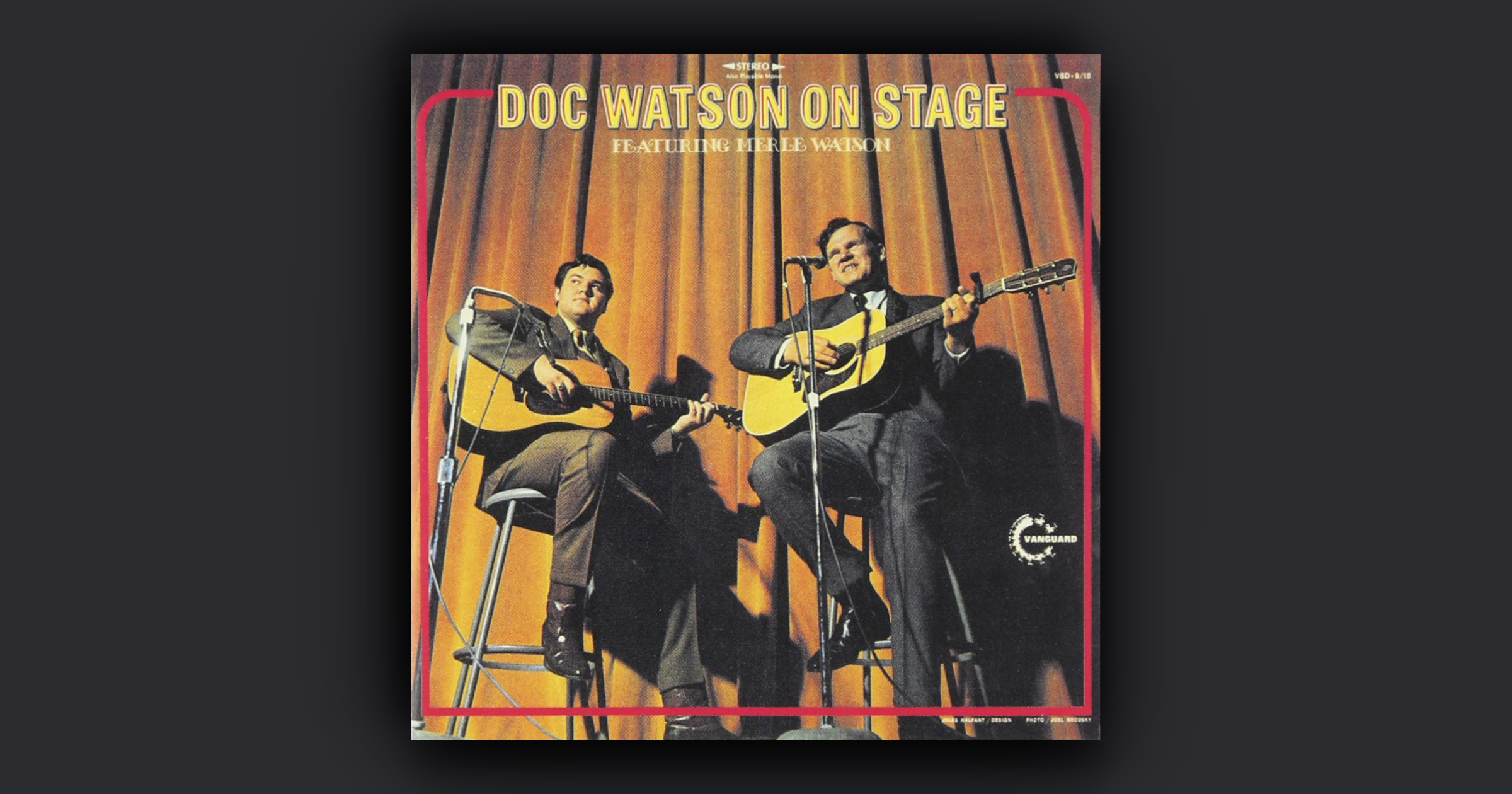

Doc Watson: Live Moments and Memories

While the late great Arthel “Doc” Watson released scores of albums over the course of his career, he only made the main Billboard charts once and peaked at a modest 193 (for his 1975 album, Memories). But Watson made a far bigger mark as a performer, often in some unusual settings — from the most prestigious concert stages down to humble living rooms.

Even though Watson wasn’t a huge record seller, few artists in the history of American music ever generated more transcendent moments. He remains revered as one of the best flatpick guitarists of all time, and MerleFest (the festival he founded in memory of his late son) stands as an essential acoustic-music event.

Here are some of Watson’s signature moments of performance, captured for the ages. (Listen to the playlist below.)

“Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms” – The Three Pickers: Earl Scruggs/Doc Watson/Ricky Skaggs, 2003

We begin with a collaboration between Watson and his fellow North Carolina legend, master of the bluegrass banjo Earl Scruggs, with the old Flatt & Scruggs warhorse “Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms” — the closing track from the live album they recorded together in Winston-Salem in 2002. The picking is as hot as you’d expect, especially on this track where Ricky Skaggs urges a solo by calling out, “Try one, Doc!” He gets gone.

“Railroad Bill” – Legacy, 2002

Legacy was the Grammy-winning retrospective album Watson made with his longtime, late-period accompanist David Holt, with songs and stories going all the way back to his earliest days playing music. The package includes a live show recorded in Asheville, North Carolina in 2001, with one of his best-ever versions of the Etta Baker Piedmont blues classic “Railroad Bill.” Watson could indeed play about as fast as a runaway train, and this features some of his swiftest guitar runs ever captured.

“Corrina” – Doc Watson and Gaither Carlton, 2020

Watson’s newest release is this live recording of some of his earliest shows in New York City, 1962 in Greenwich Village, when he was one of the rising stars of the budding folk revival. Watson performs here with his father-in-law, the renowned old-time fiddler Gaither Carlton. But what’s really notable is that Watson is playing banjo in the old style rather than guitar. It turns out he was almost as formidable on five strings as six.

“Tennessee Stud” – Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken, 1972

This Americana landmark captured a revolutionary moment, an intergenerational, country-rock summit with the Dirt Band on one side and the country/folk/bluegrass establishment on the other. And it wasn’t live onstage, but live in the studio, with the tape machine left running to record between-song conversations. That captured some of Watson’s priceless homespun pearls (“That’s a horse’s foot in the gravel, man, that ain’t a train!”), as well as what stands as his definitive recording of this stately, well-worn standard. “Tennessee Stud” made Watson a star all over again to yet another generation of roots-music enthusiasts.

“I Am a Pilgrim” – Doc Watson on Stage, featuring Merle Watson, 1971

Watson had many fine accompanists over the years, but none better than his son Merle, who was always on Doc’s wavelength. Ever modest, Doc always claimed that Merle was the better player. He was, of course, wrong about that, but Merle was a great picker in his own right. Recorded live at Cornell University, this is an excellent version of the old spiritual that also appeared on Circle. “I Am a Pilgrim” would remain an evolving onstage set piece for Doc over the years. After Merle’s tragic death in 1985, Doc would customize the lyrics in performance: “I’ve got a mother, a sister and a brother and a son, they done gone on to that other shore.”

“Blue Smoke” – Doc Watson at Gerdes Folk City, 2001

Another track drawn from one of Watson’s early-period excursions up to New York City, this was recorded during 1962-63 engagements at the legendary Gerdes Folk City nightclub. And this cover of the instrumental by Merle Travis (for whom Doc named his son) is aptly named. When he really got to cooking, Watson could play guitar so fast he just about left a vapor trail.

“Every Day Dirt” (from The Watson Family, 1963)

Ralph Rinzler, the musicologist who first discovered Doc in the early 1960s, recorded this album live at the Watson family homestead in North Carolina. It captures some of what life must have been like growing up singing and playing with Doc; son Merle, wife Rosa Lee and father-in-law Gaither Carlton are among the relatives present. “Every Day Dirt” shows off just how personable a vocalist Watson could be, although as always the real draw is the obligatory killer guitar-picking.

“The Cuckoo Bird” – The Watson Family, 1963

From that same recording, Doc plays guitar accompanied by his son Merle on banjo, covering the old Clarence “Tom” Ashley song that appeared on Harry Smith’s epochal Anthology of American Folk Music. Thanks to the familial radar that comes when blood relatives play together, the instrumental interplay is perfect. This is also a great example at Watson’s mastery of the art of call-and-response between his guitar and voice.

“What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul?” – Bill Monroe and Doc Watson, Live Recordings 1963-1980: Off the Record Volume 2

Watson’s modesty was such that his natural inclination was to regard himself as a sideman — even though he was rarely if ever not the best picker and singer in the room. But he plays the role of foil perfectly here, vocally as well as instrumentally, to Monroe’s rippling mandolin and high lonesome tenor on this live version of the first song The Father of Bluegrass ever recorded.

“Wabash Cannonball” – Doc Watson on Stage, featuring Merle Watson, 1971

Before he started playing guitar, Watson’s first childhood instrument was actually a harmonica, which he wore out so fast from playing it so much, his parents had to give him another one at Christmas. A new harmonica became a perennial favorite gift. This version of the venerable folk-music classic features Watson blowing a mean harmonica and his descending runs on guitar are also a thing of beauty.

“Your Lone Journey” – Steep Canyon Rangers’ North Carolina Songbook, 2019

We close with a bit of a wild card, in that it’s a performance by someone else. But it’s one in which the presence of Watson’s spirit looms large enough to be felt. “Your Lone Journey” is a song that Doc and Rosa Lee wrote, and it bids a poignant farewell to a loved one at the moment of death. It is performed here by Watson’s fellow North Carolinians Steep Canyon Rangers, recorded on the main Doc Watson Stage to close out the 2019 MerleFest.

Editor’s Note: David Menconi’s Step It Up and Go: The Story of North Carolina Popular Music, from Blind Boy Fuller and Doc Watson to Nina Simone and Superchunk will be published in October by University of North Carolina Press.

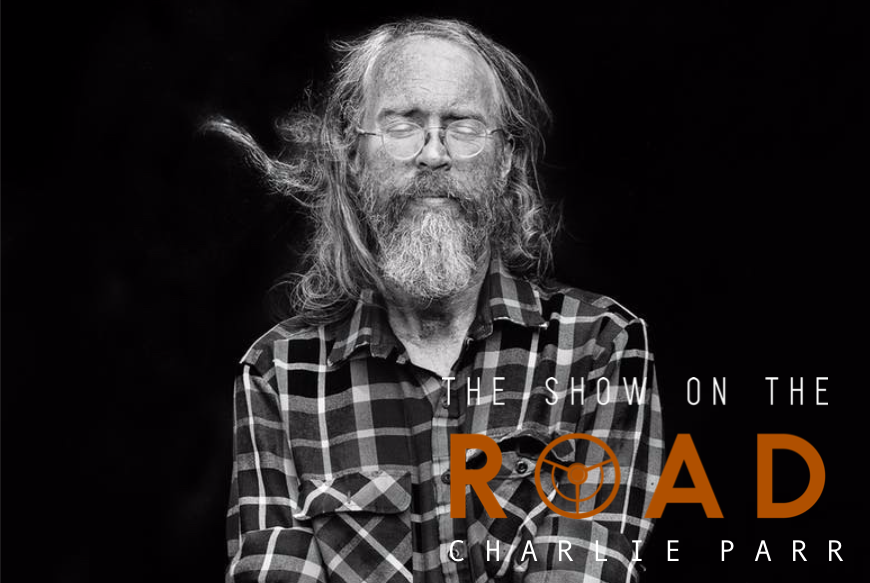

The Show On The Road – Charlie Parr

This week on The Show On The Road, Charlie Parr — a Minnesota-based folk blues lifer who writes novelistic, multi-layered stories that shine a kaleidoscopic light on defiant, unseen characters thriving in the shadows all around us.

LISTEN: APPLE PODCASTS • MP3

Parr has a new record with only his name on it, and it isn’t shiny and perfect and commercial and catchy. It’s him. It’s pure Charlie Parr and maybe that’s enough. He hasn’t moved to LA or Nashville; he’s stayed in the cold grey north of Minnesota, because that’s his home. Take a second wherever you call home right now and listen to his episode — and his new record. You might hear something different every time.

BGS 5+5: Charlie Parr

Artist: Charlie Parr

Hometown: Duluth, Minnesota

Latest album: Charlie Parr

Personal nicknames: Jeff, my actual first name. My mom calls me Jeff.

Which artist has influenced you the most … and how?

Koerner, Ray & Glover have probably had the biggest impact on me as a musician, and it’s hard to put into words exactly how. When I moved to Minneapolis in the ’80s there was so much amazing music everywhere you looked and each scene had a certain vibe to it, from jazz, funk, the beginning of whatever they were calling alt-country then, punk, hardcore to the incredibly unique West Bank folk/blues scene. I loved it all, but I lived on the West Bank and that sound that K,R&G made either together or in their parts (K and/or R and/or G) changed my life.

What’s your favorite memory from being on stage?

I’ve been lucky to have had mostly good and great experiences performing; there are so many nights that stand out it’s hard to say I have a favorite. This summer an audience in Bozeman, Montana, threw flowers on stage after my set and it really made me happy. Normally I just want to play and that’s the primary mover, but when I feel like an audience likes what I’ve done and responds with that kind of love it’s just about the most amazing thing I’ve ever felt.

What other art forms — literature, film, dance, painting, etc — inform your music?

I read a lot, mostly novels and short stories, some history and biographies, a little philosophy, and that all goes into the pot. I go to galleries when I can, and occasionally see a film, but not as often as I’d like. Everything tends to influence the music.

What rituals do you have, either in the studio or before a show?

I drink a little coffee, walk a little if there’s time and room, or at least pace. I like to warm up on the guitar if there’s a place to do that. I also really like spending time in the venue, I like to see who else is playing and meet some folks who came to the show.

Which elements of nature do you spend the most time with and how do those impact your work?

I live near Lake Superior, which is a powerful force up here for everyone, and I really like getting to go walking near the lake. When I’m on the road and there’s time I like to walk wherever there’s water; it grounds me and gives me a sense of balance.

Blue Ox Festival Stretches Bluegrass Boundaries

The Blue Ox Festival is bringing the good stuff to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, on June 13-15, with headliners like the Infamous Stringdusters, Trampled by Turtles, and Railroad Earth. Nearly all of the bands on the three-day lineup share a strong acoustic music influence. And while more than a few of these bands are stretching the boundaries of bluegrass, they’re also picking up thousands of new fans along the way.

Here are some highlights from this year’s lineup:

THURSDAY: The Infamous Stringdusters (pictured above) are back with Rise Sun, their first album since winning a Grammy. They’ll top off the night on Thursday, taking the stage at 10:30 pm and playing until midnight. Earlier in the night, fans can catch local favorites Horseshoes & Hand Grenades, approaching a decade together after meeting in college in Stevens Point, Wisconsin. The Lil Smokies and The Lowest Pair will also perform on the Main Stage, while Old Salt Union and Grassfed play the Side Stage. After midnight, Black River Revue and Chicken Wire Empire take on the Backwoods Stage.

FRIDAY: Trampled by Turtles, the pride of the upper Midwest music scene, are making their first-ever appearance at Blue Ox this year, just after a set from their friends in Pert Near Sandstone. The exceptional lineup also boasts the Travelin’ McCourys, who will play a set dedicated to Sam Bush (who bowed out of the festival to recover from a recent surgery), along with their own material. The roster also features Fruition, the Del McCoury Band, and Jeff Austin Band, as well as Americana favorites Sarah Shook & the Disarmers and Pokey LaFarge. Check out the Side Stage for sets by the Larry Keel Experience, Cascade Crescendo, Barbaro, and David Huckfelt. Once again, night owls can swoop down to the Backwoods Stage for more music — this time from Horseshoes & Hand Grenades and Jeff Austin Band.

SATURDAY: One of the most entertaining bands on the festival trail, Railroad Earth effortlessly connect fans of quality songwriting, awesome jamming, and exceptional musicianship. They’ll follow Pert Near Sandstone on the main stage – but this is not the day to arrive late. The inspired afternoon lineup features the innovation of Billy Strings, the undeniable power of The Dead South, cool insight from acoustic blues artist Charlie Parr, and the straightforward bluegrass sounds of The Earls of Leicester featuring Jerry Douglas. Grab some lunch and check out Peter Rowan’s Carter Stanley’s Eyes as well as Them Coulee Boys as the festival grounds start to fill up.

The Side Stage offers a compelling roster as well, with sets by the People Brothers Band, The Wooks, Feeding Leroy, and Dusty Heart. After midnight, Armchair Boogie settles into the Backwoods Stage, along with the Blue Ox Superjam.

Even if you can’t make it to the festival, you can watch key sets from the weekend on The Bluegrass Situation via JamgrassTV!

Photo of Infamous Stringdusters: Aaron Farrington

Photo of Trampled by Turtles: David McClister

Photo of Railroad Earth: Jason Siegel

The Bluegrass Situation, JamGrass TV Team Up for Live-Streaming at Blue Ox Music Festival

The Bluegrass Situation is thrilled to announce a partnership with Blue Ox and JamGrass TV for live-streaming from the main stage at this year’s Blue Ox Music Festival, to be held June 13-15 in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. BGS will be on hand throughout the weekend to give followers an exclusive behind the scenes glimpse of the fest’s impressive lineup of regional and national artists in bluegrass, roots, and Americana music.

Fans will be able to watch live performances at the Blue Ox Festival from the BGS homepage, in addition to seeing extensive coverage on BGS social media during each day of the festival. Camping is available on site.

In addition to multiple performances by Pert Near Sandstone, this year’s music lineup includes: Trampled by Turtles, Railroad Earth, Sam Bush Band, Del McCoury Band, The Infamous Stringdusters, The Dead South, The Earls of Leicester featuring Jerry Douglas, Billy Strings, Peter Rowan’s Carter Stanley’s Eyes, Charlie Parr, Pokey LaFarge (solo), Sarah Shook & the Disarmers, and many others.

Stay tuned to the BGS homepage June 13 to 15 for live stream updates, or check it out for yourself in person — get your tickets at www.blueoxmusicfestival.com

GIVEAWAY – Win tickets to Willie Watson and Charlie Parr at the Troubadour (LA) 12/5

Best of: Folk Alley Sessions

In 2003, Folk Alley began streaming music online to bring the best acoustic, Americana, singer/songwriter, Celtic, traditional, and world music to listeners across the globe. While their website has a whole host of things to check out, from playlists to radio shows and blog posts, we always end up on the sessions tab watching live performances by our favorite artists. Here are five performances you don’t want to miss:

The Secret Sisters — “The Tennessee River Runs Low”

We at the BGS have not been shy about showing our love for the Secret Sisters. In this performance of “The Tennessee River Runs Low,” Lydia and Laura Rogers show off their vocal blend and knack for awe-inspiring harmonies.

Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn — “Shotgun Blues”

Husband-and-wife duo Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn truly are the king and queen of the banjo. Washburn puts us in a trance right from the start of “Shotgun Blues” with her haunting vocals and steady beats on the banjo.

Twisted Pine — “Easton”

Between the mandolin chops of Dan Bui, the steady drive of bassist Chris Sartori, and the vocal harmonies of front-women Rachel Sumner and Kathleen Parks, Twisted Pine is bound to take roots music by storm in the years to come. Check out this performance of “Easton” from their debut album, Twisted Pine, to see for yourself!

Charlie Parr — “Delia”

Charlie Parr and his trusty silver resonator guitar are a perfect pair. Add in a slide, and the results are magical. In this video, Parr performs “Delia” from his 2015 album, Stumpjumper, showcasing his forward-moving picking style and beautiful but sad lyrics.

Laura Cortese & The Dance Cards — “California Calling”

Girl Power! String Power! These two phrases come to mind every time we watch a video Laura Cortese & the Dance Cards. Their arrangements and tight harmonies leave us speechless every time.