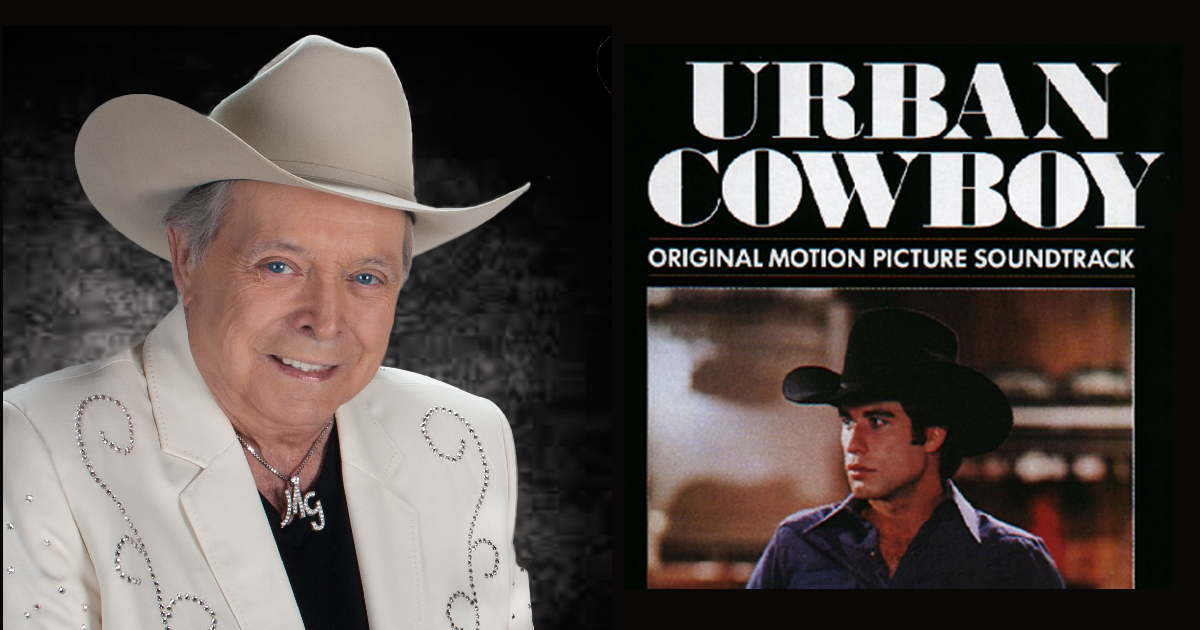

Mickey Gilley admits he wasn’t keen on the idea of installing a mechanical bull at his namesake honky-tonk on the outskirts of Houston, Texas. Nor is he shy about admitting just how wrong he was. That rodeo training device transformed Gilley’s Club into a cultural force. “The mechanical bull was never meant to be in an entertainment establishment like ours,” says the 84-year-old country star. “I thought it was a mistake, but it turned out to be a blessing. Without the mechanical bull, we never would have gotten that film with John Travolta.”

Every night there was a line for the mechanical bull. Demand was so high they installed a second bull and briefly considered buying the rights to the device in order to market it to honky-tonks around the country. Those would-be cowboys — called Gilleyrats after their favorite gathering spot — would compete to see who could stay on the bucking bull the longest, and that contest became the centerpiece of James Bridges’ 1980 film Urban Cowboy, featuring John Travolta in his follow-up to Saturday Night Fever. Exchanging the New York City discos for this dusty, Lone Star honky-tonk, he stars as Bud Davis, a small-town kid who moves to the big city and becomes a master of the mechanical bull.

The film culminates in a showdown with his nemesis, played by Scott Glenn, over the affections of a scene-stealing Debra Winger. As drama goes, this test of saddle skill is anticlimactic, as there is nothing at stake beyond macho pride. Bud isn’t fighting to escape his life (as his character in Fever did) nor to stay at Gilley’s. He’s just fighting. Though never quite satisfying as drama, Urban Cowboy is still fascinating 40 years later as a documentary about Gilley’s and the particular culture that grew up around it.

Gilley and his business partner, Sherwood Cryer, opened the place in 1970. At the time Gilley was only a regional star, with his own TV show in Houston and enough name recognition to open a club. (Being cousins with both Jerry Lee Lewis and Jimmy Swaggart didn’t hurt, either.) In 1974 he had a surprise hit with “Room Full of Roses,” which only brought more attention to his honky-tonk. He played there regularly and invited friends to fill in for him when he was on the road. The place grew into something like a theme park, with a dance floor roughly the size of a football field, several bars, tons of games, even a rodeo arena. “This place is bigger than my whole hometown,” Travolta’s character says when he first steps foot in the place.

Urban Cowboy captures the energy of Gilley’s Club in frenetic long takes that put you right at the bar or out on the dance floor. You can almost smell the sawdust and beer. Gilley even performs during a couple of scenes, as does Charlie Daniels, and the shots of couples shuffling across the floor in tight, fluid choreography are among the film’s highlights.

By the time a suspicious fire destroyed Gilley’s in 1990, the place and the film had already left a deep impression in popular culture. It introduced western wear as high fashion: tight jeans and big hats worn by guys who never rode the range (or a bull, for that matter), but still bought into the mythos of the American cowboy. And its soundtrack, featuring Bonnie Raitt, Boz Scaggs, and Kenny Rogers, peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 and produced chart-topping country singles such as “Lookin’ for Love” by Johnny Lee, “Could I Have This Dance” by Anne Murray, and “Stand by Me” by Gilley himself.

For our latest Roots on Screen column, we chatted with the club’s namesake about accidentally recording a hit single, flying with Travolta, and assaulting the sausage king.

BGS: How did you get to a point where you could open a massive honky-tonk with your name on it?Gilley: I grew up in Louisiana and got two famous cousins, Jerry Lee Lewis and Rev. Jimmy Swaggart. Jerry Lee was my hero, because without him I probably wouldn’t have gotten in the music business. He came to Houston in ’57 and I saw how well he was doing. I was working construction making $1.25 an hour and that’s when I threw my hat in the ring. Seventeen years later I cut “Room Full of Roses” by mistake and it turned out to be my first No. 1 song. After that I got to tour with Conway and Loretta and next thing I knew John Travolta came knocking on my door. Everything broke loose.

How does somebody cut a hit single by accident?

I had a little TV show in the Houston market. One night I walked into Gilley’s and the lady who had the jukebox called me over and says, “Today on your TV show you did my favorite song, ‘She Called Me Baby All Night Long.’” It’s a Harlan Howard tune. She told me she’s in the jukebox business and if I would record that song, she’d put it on every one of her jukeboxes. I said, “Ma’am, I ain’t made a record in probably three years. The show is doing well. The club is doing well. I don’t really make records anymore.” She said, “Just make that one song for me.”

Well, as you know, back then they had 45s and you had to have an A side and a B side. I went in to cut “She Called Me Baby All Night Long” and for the flip side, I picked “Room Full of Roses.” It’s an old George Morgan song from the late ‘40s or early ‘50s. Lorrie Morgan’s father. I started the arpeggio on the piano and got maybe 30 seconds into it and then stopped. My bass guitar player looked over and said, “What’d you quit for?” I told him it sounded too much like Jerry Lee. And he says, “Who cares? Nobody’s going to hear it. It’s a B side!” So I recorded it. Didn’t think anything about it.

I took the record around to radio stations where we were buying time to advertise the club — “Gilley’s! 4500 Spencer Highway! Pasadena, Texas!” — and I asked if they would play the record when they did the spot on the club. I remember Bruce Nelson at WKNR asked me which side I wanted him to play. I said, “Either side you want. Doesn’t matter to me.” He looked at both sides and said, “I think I like that flower song.” He played it and it shot up the charts. Playboy Records picked it up and took it national for me in 1974.

What was a typical night like at Gilley’s during its heyday?After the film Urban Cowboy came out, it was packed every night. I never seen anything like it in my life. It went on for about three and a half years. It was totally jam-packed, seven nights a week. People wanted to be a part of what it was all about. They just came out to have a good time. We had a lot of things in the club you could do, too. We had the two mechanical bulls, plus we had quite a few pool tables spread out through the club. Pinball. Punching bags… you know, things of that nature that people would get a kick out of.

How many stages did you have?

We had just the one big stage for music. Of course, my business partner built a rodeo arena back in ’85 or ’86 and hitched it onto the club, because he wanted to stay ahead of Billy Bob’s down in Fort Worth. The concerts we had in there worked out pretty good, because we had Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, George Jones, George Strait. People like that do real good in a rodeo arena, but other than that, it was just a big building that we didn’t need.

How often were you playing the regular stage?

I worked the club up until 1985. But I got into a squabble with him about the way the club was running and what was going on, and we got in a lawsuit. I got the club closed down, I got my name off of it, and later it was set on fire and burned. It was arson, but I don’t know who did it, you know? It went up in flames and no more Gilley’s in Pasadena, Texas. But we have a Gilley’s in Treasure Island in Vegas. We have two in Oklahoma and one in Dallas.

What do you remember about filming at Gilley’s?The main thing I remember was that we had to do it during the day, daylight hours, because we operated the club at night as the regular nightclub. They closed all the doors and tried to make it as dark as they could. I remember the director hollering, “More smoke! More smoke!” to make it look more like a night at the club. They’d start early in the morning and go all day, shooting the parts they had to have. I never had been in a film of that caliber before, so it was different for me. But it was fun.

Was the Urban Cowboy Band something you put together especially for the film?

We had a band there that was playing the club, but I took them on the road with me and renamed them the Urban Cowboy Band when the film came out. Paramount Pictures told me it was OK to use it, so that’s what we did. We were awarded a Grammy for the song “Orange Blossom Special,” which I played piano on. But there were some great songs in the film. “Hello Texas” was written by a Texas guy by the name of Brian Collins and sung by Jimmy Buffett. That’s a great song. We also had Charlie Daniels doing “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” in the film.

Your version of “Stand by Me” was a big hit as well.

It was originally recorded by Ben E. King and written by Leiber and Stoller. The song was brought in by the producer, who was wanting to do what he called a “grudge dance” in the film. They picked “Stand by Me” and asked me to do the song. I was a little reluctant but the arrangement they put on it made it a different song than the Ben E. King version. When we got the song recorded, people were raving about it, and it turned out to be a hit. Now I close my shows with it.

What was it like having someone like John Travolta in your club every day? What was he like to work with?Well, the one thing that John and I had in common was we both loved aviation. At the time, he was working on his pilot’s license, and I got to fly with him. I was so excited about the fact that I was getting to fly with the star of Urban Cowboy. He had just come off of Saturday Night Fever and Grease, so I’m in awe. I’m just an old country boy that’s had quite a few No. 1 songs, but I never had the popularity John Travolta had. He was working on his pilot’s license at the time, so I went up with him a few times. He went on to fly the big jets, which I’m sure is exciting for him. I never got that far in my career. I got to fly some jets, but they were like the LearJet and the Citation — nothing like the 747 he was flying.

How did the success of that movie and the soundtrack change your career?

It changed my life, because the record company put me with a different producer and he started picking songs like “You Don’t Know Me,” “That’s All That Matters to Me,” “Headache Tomorrow (Heartache Tonight),” and “Put Your Dreams Away.” They were all hits for me and opened more doors for me, as far as casino dates in Reno, Vegas, and Atlantic City. I wasn’t just known as a honky-tonk piano player anymore. I was known as a country performer and it gave me a little more clout. I got to play for two presidents. They gave me a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, invited me to come to Hollywood and do some acting roles, and I did The Fall Guy, Fantasy Island, The Dukes of Hazzard, and Murder, She Wrote. I had a scene in Murder, She Wrote where I grab Jimmy Dean, the sausage king! I grab him by the collar and shake him. Sometimes I show that clip in my show and say, “Look at that! I’m trying to shake the sausage out of Jimmy Dean!”

You’re still playing a lot of those songs from Urban Cowboy on tour, right?

Johnny Lee and I have done well by doing the music from that soundtrack and we called it the Urban Cowboy Reunion Tour. I wish we could have gotten more people involved, maybe Charlie Daniels or Bonnie Raitt. But we did pretty good just the two of us. I remember playing a casino down in Louisiana, and at the end of the show I looked at Johnny and said, “Do you realize those people out there dancing wasn’t even born when we did the film?” I think they come out here to see if we’re still alive!

Photo credit: Courtesy of 117 Entertainment