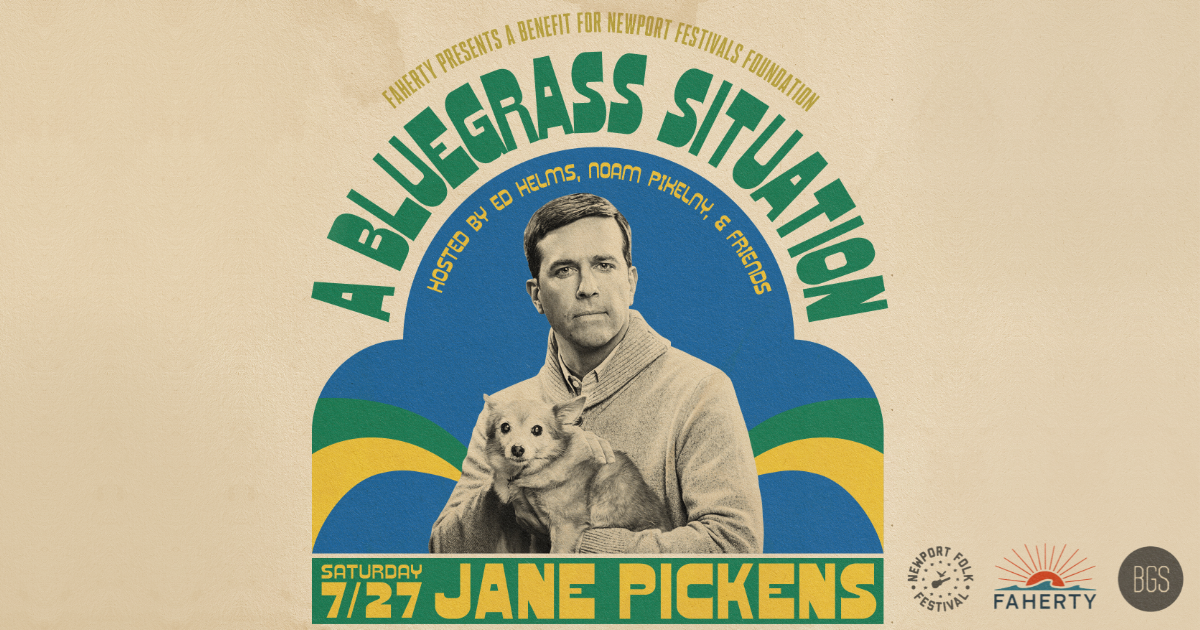

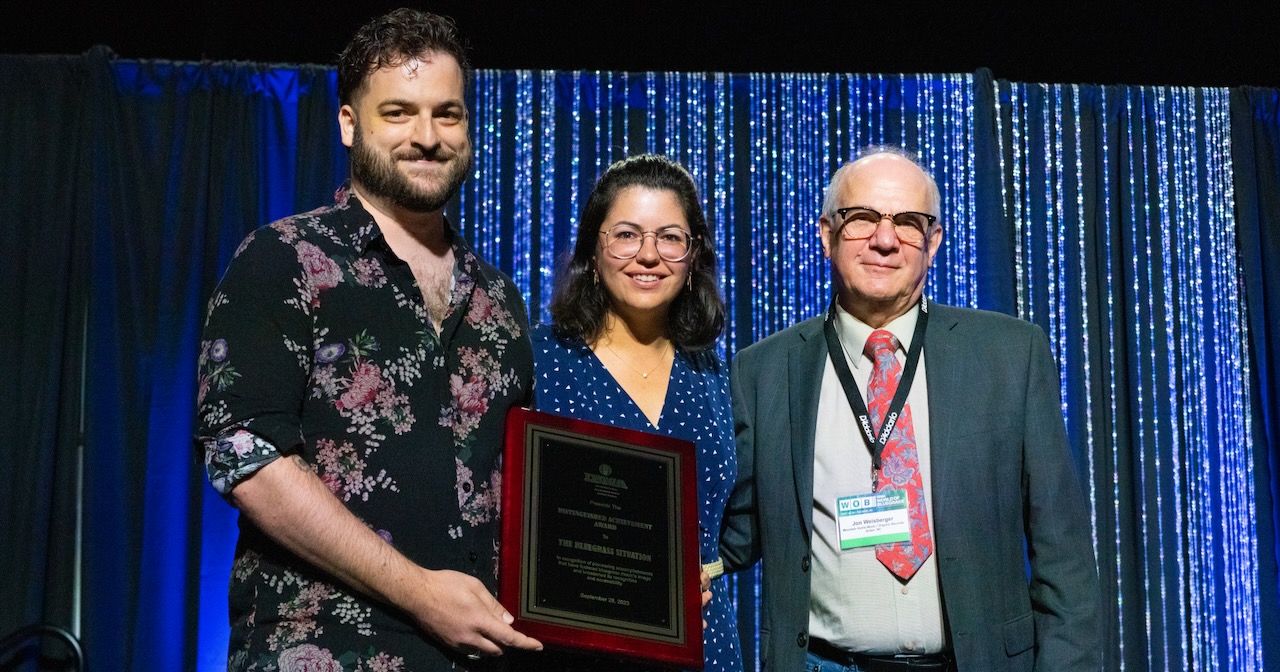

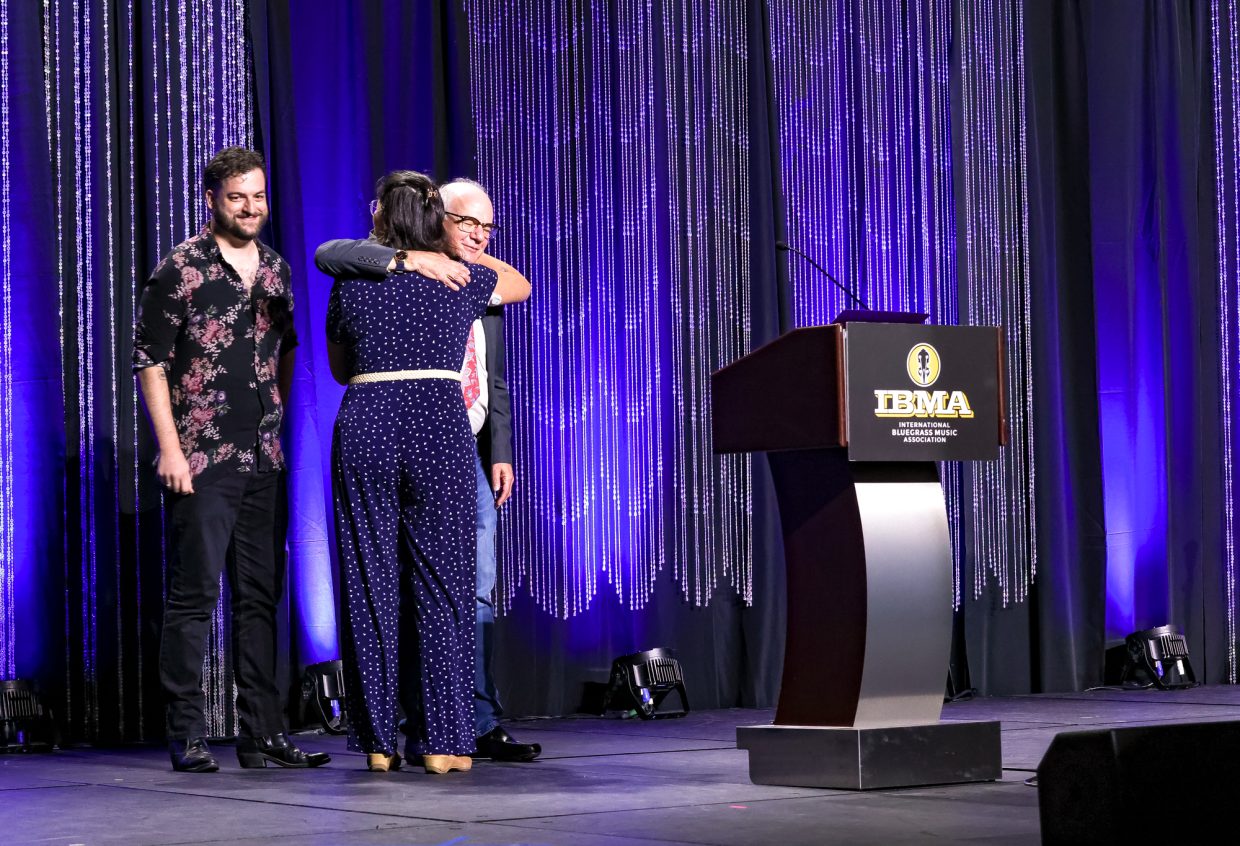

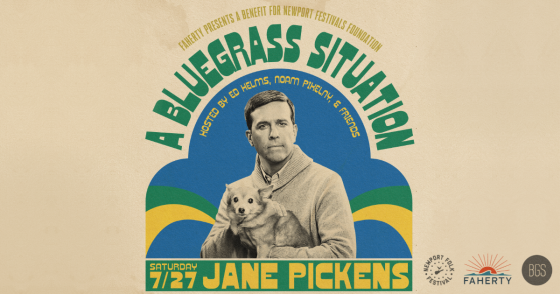

On the evening of Saturday, July 27, BGS returned to the fabled Newport Folk Festival for the first time in a decade to host a very special after show event, A Bluegrass Situation, hosted by our co-founder Ed Helms, Noam Pikelny, and friends. Held at the Jane Pickens Theater in Newport, Rhode Island, the evening – which benefitted the Newport Festivals Foundation – was produced by BGS executive director Amy Reitnouer Jacobs in partnership with the festival team. The star-studded concert sold out almost instantaneously.

“In today’s overcrowded music festival market, it can be rare to find that place that maintains both comforting familiarity and curatorial daring do,” said Reitnouer Jacobs. “One of the last bastions of this kind of audacious event production is Newport Folk Fest… Saturday marked exactly ten years to the day since the last time BGS curated a stage for Newport. Here’s hoping our next return to Fort Adams will be far sooner!”

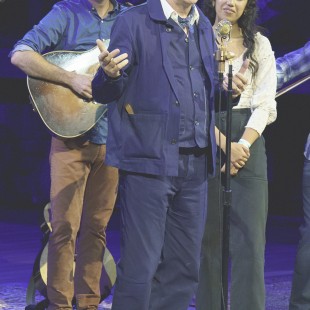

Helm’s own band, the Lonesome Trio – with Jacob Tilove and Ian Riggs – served as the evening’s house band, including pal Noam Pikelny (Mighty Poplar, Punch Brothers) on banjo. They kicked off the evening with a pair of bluegrass classics and were on hand throughout the show to back up many BGS friends & neighbors, including Rett Madison, young mandolin phenom Wyatt Ellis, frequent BGS collaborator Langhorne Slim, bluegrass banjo trailblazer Tony Trischka, and more.

Festival mainstay Billy Bragg made an appearance (appropriately covering Bob Dylan), as did Alisa Amador, who also joined singer-songwriter Kaia Kater on a performance of Kater’s original song, “Nine Pin.” Kater was back on stage again later in the evening for a banjo throwdown with Helms, Pikelny, Trischka, and Rhiannon Giddens all picking “Cluck Old Hen,” which brought down the house. Andrew Bird and Madison Cunningham, who performed Buckingham Nicks at the festival during the weekend, stopped by for two songs, while elsewhere in the set Giddens called on her musical collaborator Dirk Powell – and Powell called on Giddens – for a pair of selections as well.

“Ed and Noam gathered a gaggle of old friends and buzzy new talent for one of our best bluegrass jams yet,” Reitnouer Jacobs continued. “Rhiannon Giddens and Langhorne Slim warmed up backstage alongside artists making their Newport debut, such as Wyatt Ellis and recent BGS Artist of the Month Kaia Kater (whose supergroup New Dangerfield would take the main stage the next day). Rett Madison dazzled us with sartorial style and voice, and surprise guests dropped by – like Tony Trischka and John C. Reilly. Like any good bluegrass jam, you never quite knew who was going to take the next break, but you knew it was going to be damn good.”

Reilly – arguably best known as an actor/comedian – is also an accomplished Americana songster, and joined his old friend Helms on a rendition of the Stanley Brothers’ “It’s Never Too Late,” to the delight of the Jane Pickens Theater crowd. To close the evening, the full cast of stellar artists, musicians, and creators came together to jam on a few rousing group numbers, including a touching a capella encore of “Amazing Grace.”

Newport Folk Festival is a sacred space in our roots music community; we were so proud and honored to return to the event to host A Bluegrass Situation and offer a stage to so many of our dearest friends in bluegrass, folk, and Americana. Relive our special after show with these photos from the evening:

All photos by Nina Westervelt and Josh Wool, as noted. Lead Image: Nina Westervelt.