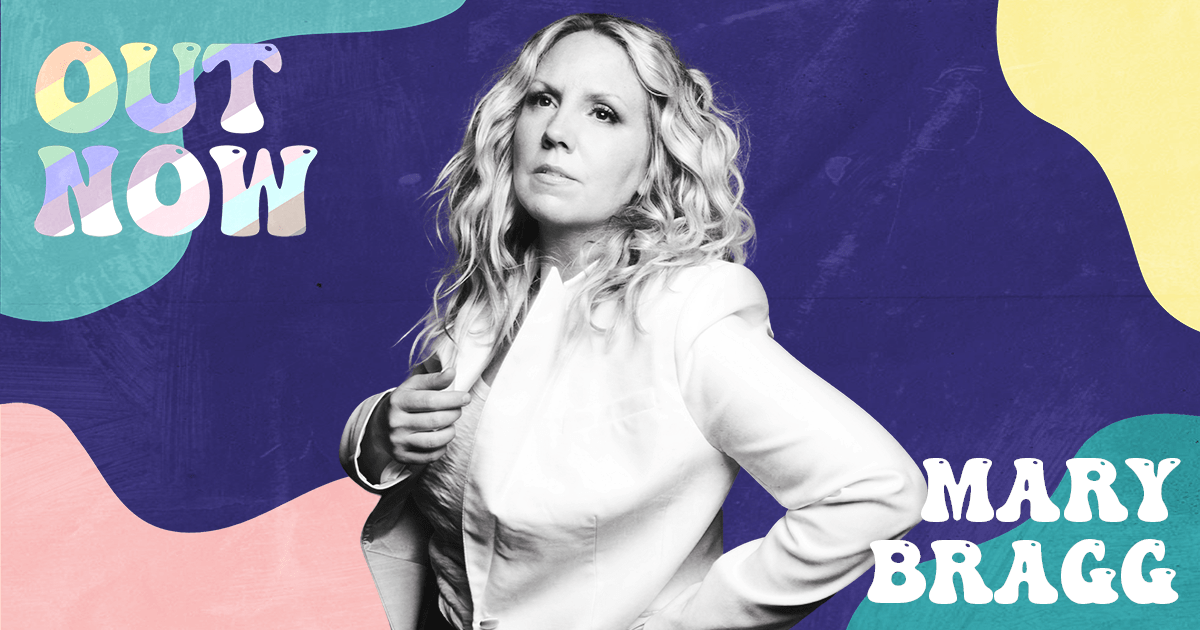

Mary Bragg crafts music with beauty and pain, vulnerability and authenticity, and raw emotions. Mary played Queerfest 2022 at The Basement East in Nashville. Tonight, January 23, 2024, she will be back on stage at The Basement to celebrate her new single, “Only So Much You Can Do.”

In addition to being a phenomenal songwriter and vocalist, Mary is also a producer. In 2022, she earned a Master of Arts in Songwriting and Production from Berklee NYC, elevating her skills to the next level. Her self-titled album centers around self-discovery with tender lyrics that touch on love, loss, and self-esteem. Mary writes compelling music filled with nostalgia and honesty. We’re delighted to feature this incredible artist, Mary Bragg.

What would you say is your current state of mind?

Mary Bragg: Wow, what a way to start the conversation; I love it. My current state of mind is as follows: Grateful – for my life, my love, my work. Steady – managing a wonderfully robust docket of creative work while continuing to establish balance in my everyday life and internal dialogue. Excited – always, about a song. Several actually, new ones, ever percolating.

When I co-write, songs typically arrive at a near-complete form pretty quickly, but when I write alone, I’m much more patient with the process. I move through the world keeping my antennae up, looking for a way back into a lyric I’m working on that gets me in the gut. I’m obsessed with it.

What would a “perfect day” look like for you?

Being a touring musician is a funny thing, because touring life is very, very different than home life. I’ll frame the “perfect day” for you on the road beginning at 2 or 3 p.m., when we load in and have a perfect soundcheck with a killer engineer. Doors at 6. Show at 7. (Did I mention I love early shows?). Merch table mayhem at 9. Cocktail at 10. In bed by 11:30, sleep until 8. Drive, fly, etc. to the next town, repeat.

At home, I’m an early bird. Up by 6:30 or 7, coffee, eggs, journal, write, attempting to avoid technology for a few hours. 11 a.m. workout. Afternoon – back to work – emails galore, phone calls, Zooms, everything. I wear a lot of hats (artist, writer, producer, occasional teacher), so there’s a lot of juggling to do. By 7 p.m. I force myself to stop working; my darling fiancé, by this point has probably created a ridiculously beautiful meal for us. I used to think I was a good cook until I met her. She blows me away every time she prepares a meal for us. It’s the best. And I’m a great dishwasher. Watch a little TV after dinner (okay sometimes during), and hit the sack by 10 p.m., otherwise I turn into a pumpkin on the couch.

Why do you create music? And what’s more satisfying to you, the process or the outcome?

The process is exhilarating – as a writer, the actual singing and playing in a small room, making music and hearing it travel through a space is one of my favorite things. No audience, just the song in a room. Hearing your thoughts as you’re framing them in melodic form is a bit of a head trip that has its own immediate reward. In the studio, there’s a whole other bag of satisfying tricks to uncover and of course performing live has its own rewards as well, mostly connecting with other people who feel what you feel. And, on the road I’m able to focus more on the enjoyment of singing; pushing my voice to try new things on the fly is incredibly fun. Up until that moment of live-show-exhilaration, I’m so focused on the writing and producing, but by the time I take it to the stage, I can really let go and dig back in to the music itself.

Could you tell us about your single that came out today?

Ah, my new single! “Only So Much You Can Do” is about chasing joy in the company of another person. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about that New York Times article about the secret to happiness – and how relationships are the key to it. We are pack people; we need each other; we need other human beings around us in order to be our best, happiest selves. Friends plus community plus honesty equals joy. I wrote this song with my dear friend, Bill Demain, during the pandemic over Zoom; we craved connection again, waited eagerly for it to return. Now that we’re out from under it, the song is a nice reminder to spend time – actual face time – with your people; it sure does a lot of good.

Who are your favorite LGBTQ+ artists and bands?

Rufus Wainwright, The Indigo Girls, Brandi Carlile, Aaron Lee Tasjan, Jobi Riccio, Liv Greene.

What does it mean to you to be an LGBTQ+ musician?

Well, I’m a person who is a songwriter and artist who is also bisexual living in a world that, at the moment, likes to extend a great to deal of judgment, disdain, disapproval, and harm to people in the LGBTQ+ family. Most of the time I feel as happy as the next person, then I’m reminded of the threats to our community, to my own family, and I remember how important it is to speak my experience, write through my own pain, and sing about the things that break my heart.

I think every human being deserves to tell their story, express their feelings, and be heard. If I can do that – tell my own story of coming out, leaning in to love while experiencing deep, simultaneous loss, then reclaiming joy and autonomy – maybe some additional jolt of kindness, empathy, and love will be injected into the world.

In 2021, you moved from Nashville to New York City to pursue a Master of Arts in Songwriting and Production at Berklee NYC. How did this educational pursuit impact your creative process and the way you approach your work today?

It’s funny – getting a masters degree might suggest you’re taking your work very seriously, going deeper on process and theoretical approaches to your craft. While I did very much feel that way during the program, by the end of it I felt a newfound sense of taking myself less seriously. I wanted to reconnect with a sense of lightness, play, curiosity, remembering that songs are a gift, that humans have so much in common, and we all just need to be acknowledging those commonalities more frequently and willfully. The more I can get to the heart of those feelings, and sharing them, the better.

Also, at the end of my thesis defense, one of my professors said to me, “Remember who you are.” It was such a nice thing to hear, because I do know who I am, what I stand for, and what I want to do with my life. All I have to do when I get distracted, spin out, or lose track of my focus is remember who I am.

Your latest album addresses the universal themes of self-love, acceptance, discovery, loss, beauty, and pain. How did you personally grapple with these concepts during your own transformative journey, especially in the context of your relationships and coming out to your family?

Woof, the grappling was tough, but my gut was clear: I knew who I loved, what that meant for my place in a world that is obsessed with classifications, and how hard it would be for some people that I love deeply to accept.

I was raised in a huge, very conservative Christian family in South Georgia and coming out to them was the hardest thing I’ve ever been through. I love them so much, they love me so much, but many of them feel quite strongly that I’m, you name it, “living in sin,” “going to hell,” “choosing a ‘lifestyle’ that is wrong.” What I know in my bones is that none of that is true. The love I have for my partner and soon-to-be wife is as real and deep as any hetero relationship I’ve ever had or witnessed. Standing firm in that belief while also trying to hold on to relationships in my family that I don’t want to lose is pretty tough, but I’m grateful that my gut speaks very loudly and I have no interest in tamping it down.

Photo Credit: Anna Haas