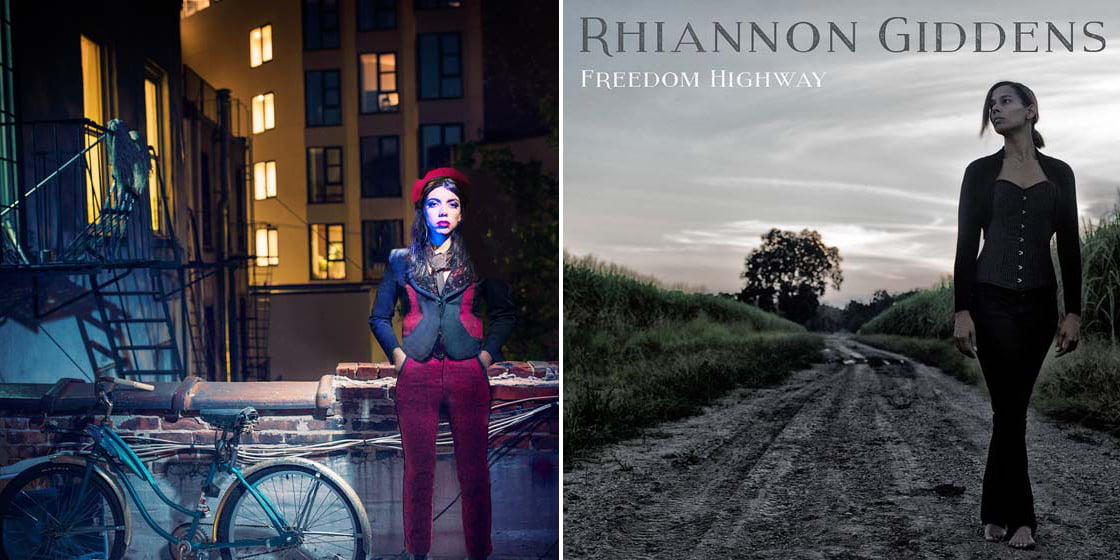

Way back in January, we proclaimed 2017 to be the “Year of the Banjo” and predicted it would be a stellar year for women in roots music, as well as the more justice-minded songwriters in our midst. All these months later, our intuition proved correct on all counts. And we are thrilled by that. Having Alynda Segarra and Rhiannon Giddens reign supreme in our BGS Class of 2017 is an absolute honor. Both women took on tough thematic terrain with grace and gravitas, and we couldn’t be more proud to support them and all the other fantastic artists who make the BGS roots community so artistically inspiring and culturally important. — Kelly McCartney, BGS Editorial Director

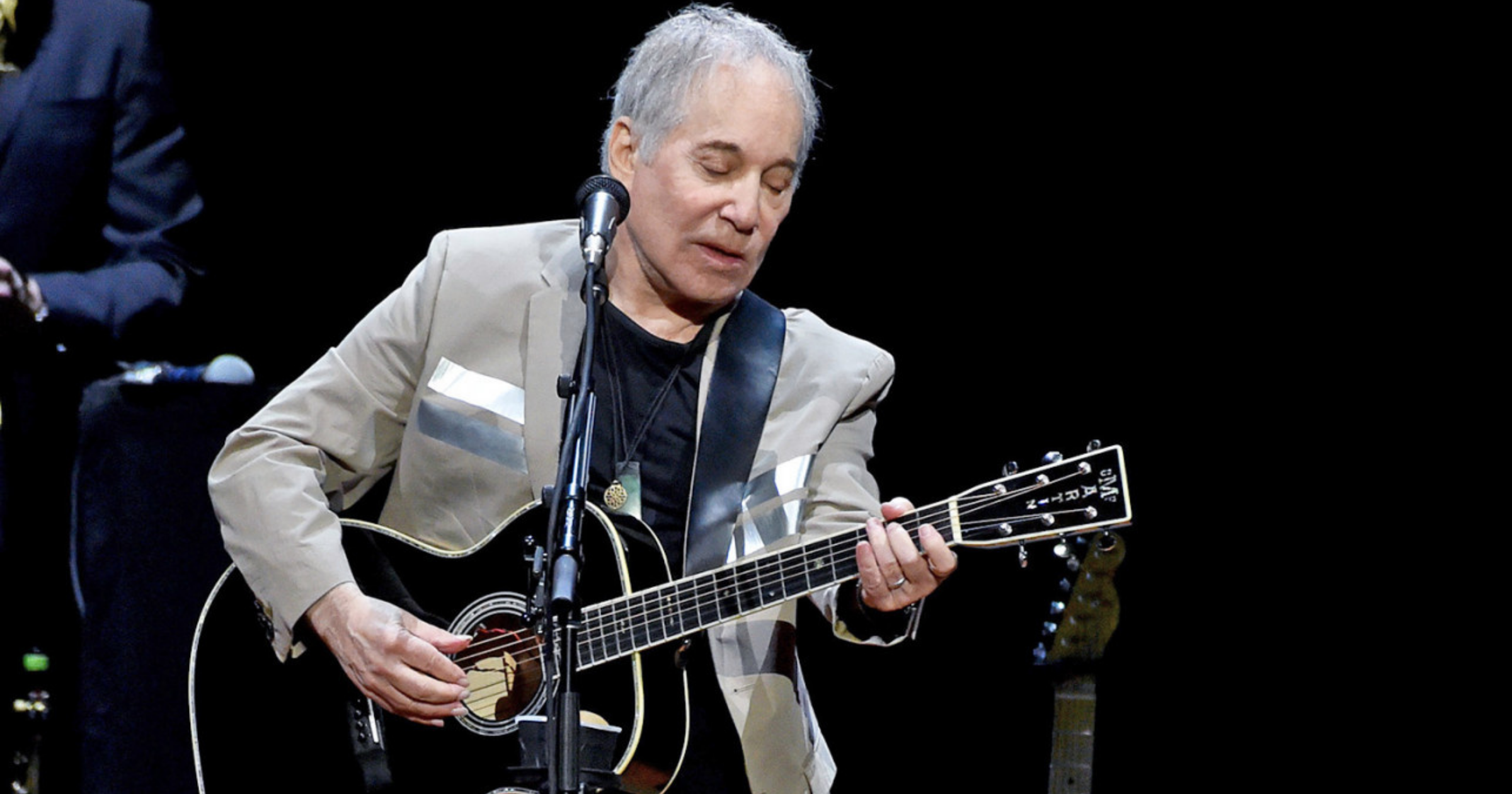

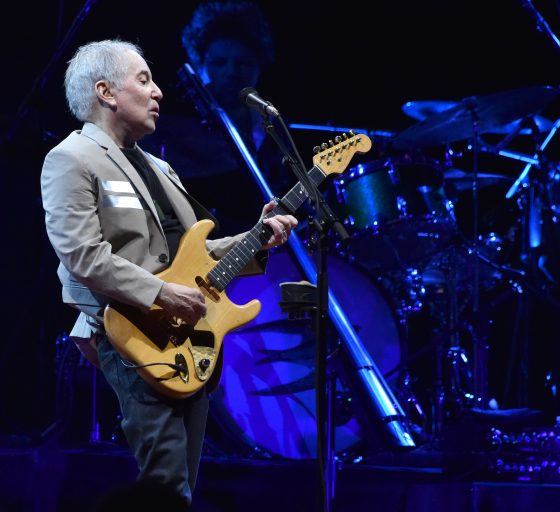

Co-Valedictorians: Hurray for the Riff Raff, The Navigator / Rhiannon Giddens, Freedom Highway

In a year rampant with talk of division — coasts vs heartland, white vs people of color, red vs blue — many artists, thinkers, and activists have attempted to bridge these divides by zooming out and broadening perspective, pointing to the core commonality of our humanity. With The Navigator, Hurray for the Riff Raff accomplishes this same unifying goal, but with the exact opposite approach. Led by Puerto Rican-American Alynda Segarra, they zoom in, viewing these divisions, these cultural and societal rifts, through a microscope trained on New York City, magnifying a Puerto Rican neighborhood and a fictitious young Puerto Rican girl, Navita. The album’s concept — granular, focused, and minute — doesn’t alienate listeners with this specificity. Rather, it plays like a colorful movie entirely enclosed within its own soundtrack, relating Navita’s heart, soul, and story to an audience that, for the most part, would feel they could never relate to a woman like her. Segarra and Hurray for the Riff Raff demonstrate through The Navigator that we ought not shy away from the intensely personal, singular, individual aspects of identity and identity politics for the sake of “coming together.” What’s more, they’ve posited a record that, taken separately, the message, concept, and music each stand on their own respective feet, but together, amplify and augment each other. The message is incredibly clear: We need not gloss over the intricate elemental parts of our differences to understand, appreciate, and love each other. Pa’lante! — Justin Hiltner

If 2017 saw an influx of banjo-centric projects, it also turned out to be a year when music’s political stakes rose ever higher. Singer/songwriter Rhiannon Giddens pairs both, using her instrument as a historical beacon that traces a line from slavery to the growing spate of police brutality. Through narratives about slave mothers, church singers, young men in the crosshairs, and more, Giddens uses these personal stories to explore their ongoing political resonance. Beginning with “At the Purchaser’s Option” — written from the vantage point of a slave mother forced to contend with her baby’s future as a commodity rather than a consciousness — Giddens sews together a quilt of American roots music that is as varied as the stories it encompasses. She explores old-time songs, reels, blues, funk, gospel, and more, stitching her way into and through the rich traditions that inform her craft and comprise her heritage. “Better Get It Right the First Time” blends funk-blues, a rap intersection, and Giddens’ authoritative vocals to challenge how states view and police Black male bodies, while the instrumental “Following the North Star” says everything about that experience through a rhythmically charged dialogue between banjo, drums, and castanets. The relationship between art and politics on Giddens’ new album is not an explicit call to action, but a reminder about the power of stories — both melodic and lyrical. As Giddens admits on “Birmingham Sunday” — about the 1963 church bombing — “All we can do is sing you a song.” — Amanda Wicks

Best Travel Buddy: Becca Mancari, Good Woman

Becca Mancari’s debut album is a world unto itself. Over the course of 33 minutes, the Nashville singer/songwriter crafts atmospheric Americana imbued with a haze that brings to mind the faded edges of a sepia-toned photograph. Born in Staten Island, raised in rural Pennsylvania, and having spent time in Florida, the Appalachian region of Virginia, and even India, Mancari has experienced firsthand the significance of place. It’s only fitting, then, that on each of the album’s nine tracks, Mancari has created an environment to get lost in. It’s a notion that extends beyond Good Woman’s sonic palette and is carried out visually in the album’s music videos. In the video for the title track, Mancari embarks on a snowy walk in the Arizona wilderness with the plaintive landscape providing the perfect backdrop for her rumination on what, in fact, constitutes a “good woman.” Mancari seemingly walks right out of that snow storm and into Arizona’s breathtaking sunny expanse for the accompanying video for “Golden,” while the slow-burning “Arizona Fire” also finds its staging area in Arizona’s canyons. On the standout “Summertime Mama,” which waxes poetic about a warm-weather crush, Mancari sticks closer to home by offering a glimpse into a carefree summer day she spends in Nashville with her girlfriend and fellow songwriters Jesse Lafser and Brittany Howard, with whom she plays in a side project dubbed Bermuda Triangle. Cruising with the windows down en route to an impromptu fishing trip and then onto a nighttime gig, Mancari’s adventures mirror the song’s breezy veneer. Just as Good Woman expands and contracts across terrains, Mancari crosses sonic bounds with her dream-like reflections, making her one of the most significant songwriters to come out of Nashville this year. — Desiré Moses

Best Reminder to Stop and Breathe: Bedouine, Bedouine

There’s no point in talking about Bedouine’s self-titled debut in anything other than colors. Between the rose-tinged “Heart Take Flight,” the dusty blue “Back to You,” the gold-flaked “Summer Cold,” and the silver-inflected “Solitary Daughter,” singer/songwriter Azniv Korkejian’s album hangs like a painting. That’s all thanks to her dusky voice, an easy, somnambulant tone that fits colorfully against Virginia label Spacebomb’s trademark strings. In between songs about her native Syria and her life in Los Angeles, the nomadic Korkejian details a romantic relationship that caught her off guard and encouraged her to stay. Rather than train her gaze on her lover, though, she holds up a mirror to herself and traces the effect love has on her. She defiantly projects her independence on “Solitary Daughter,” gives herself permission to enjoy new love on “Heart Take Flight,” and inevitably questions her lover’s commitment on “Skyline.” Bedouine reflects notes of Leonard Cohen, Nick Drake, and other poetically driven but somber-toned singer/songwriters, but in the end, its creator has captured a colorful mood that remains solely her own. — AW

Most Likely to Kick Your Ass While Breaking Your Heart: Caroline Spence, Spades & Roses

In a year that kicked off with the Women’s March and seems to be ending on scores #MeToo moments, Caroline Spence‘s “Softball,” from Spades & Roses is an anthem for any woman who is sick of battling on a different playing field. In the hands of the Nashville-based Spence, this is done through the artful metaphor of softball: an unnecessarily gendered sport that keeps women from even having a shot at the big leagues. With a delicate chug of guitar and the soothing coo of Spence’s voice, it’s just one timeless moment from Spades & Roses, a collection of stunning folk songs that explore both the world inside of her own bedroom and the world at large. Spence is self-aware in romance on “All the Beds I’ve Made,” ready to surrender on “Slow Dancer,” and eager to fight on “Softball,” showcasing a keen knack for folk songs often dripped in rock and packed with poetic, artful lyricism. Produced by Neilson Hubbard (The Apache Relay, Matthew Perryman Jones) and featuring Grand Ole Opry fiddler Eamon McLoughlin and cellist David Henry, the album puts Spence’s pitch-perfect, breathy vocals at the center of songs which effortlessly jump from personal confessions to feats of narrative storytelling. “I’ve been playing shows out West with no guarantee that anybody’s ever gonna give a damn about me,” she sings on “Hotel Amarillo,” a track that encapsulates the experiences of any musician who’s slugged through date after date with barely enough money made to keep on the road. But, in her hands, it’s also a study of choices, and all that we’re left to leave behind when we follow our dreams. It’s well worth giving a damn about, indeed. — Marissa Moss

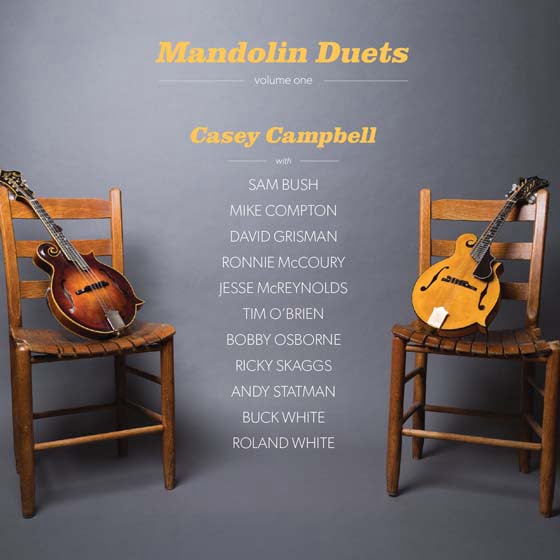

Best Addition to the Time Capsule: Casey Campbell, Mandolin Duets, Vol. 1

Bluegrass is unique among genres in that its living legends — the men and women who helped create and shape it — have never been set apart from the fans, amateur players, and up-and-coming talents. They not only mingle and interact freely with all of the above, but they actively facilitate the future of the music and the greater community, as a whole, by mentoring and shepherding young people. Mandolinist Casey Campbell quite literally grew up at the feet of a host of these living legends, so it’s fitting that, for his first album, Mandolin Duets, Vol. 1, he called upon 11 of these heroes and mentors, each showcased in their own intimate, beautifully pared-down duet. The record is a treasure trove of bluegrass mandolin and the players who have pioneered the form. Grand Ole Opry members Jesse McReynolds and Bobby Osborne hold down the traditional end of the spectrum, while David Grisman and Sam Bush test the waters on the fringes of bluegrass, with all iterations and styles in between represented. Campbell’s own Monroe-infused, clean, studied picking anchors each track, providing the perfect artistic sounding board for each of his guests. This is, by all accounts, a niche album within a niche genre, but the music doesn’t necessitate a bluegrass history lesson or individual bios for each mandolin guru to be fully appreciated. If the future is fair, this record will join the ranks of Skaggs & Rice and Bill Monroe & Doc Watson’s Live Duet Recordings as one of the most important bluegrass duet records ever made. — JH

Most Likely to Cause Shivers, Sobs, or (Whiskey) Sips: Chris Stapleton, From A Room: Volume 1

Chris Stapleton’s magnetic vocals find new forms of expression on From A Room: Volume 1. Mainstream country songs like “Them Stems” prove he can play the game alongside fellow chart-toppers like Thomas Rhett and Luke Bryant, but he’s most successful when he bucks popular trends and follows his own proclivities. With emotionally strained songs like “Either Way,” which reinforce comparisons to George Jones, Stapleton not only shows off his magnanimous voice, but also its ability to communicate the most painful of experiences. “Either Way” examines the nebulous area in between love and loss, when two people realize the plateau they’ve reached as a couple won’t be overcome. Whether they stay together or decide to leave, Stapleton admits, “I won’t love you either way.” It’s the resigned dip in his vocals before he admits the line that rings forth with such agonizing honesty. He treads in a bluesy tradition with “I Was Wrong” and “Death Row,” both of which find his voice exploding past the rafters with howling pleas. Thematically, the album toes country music’s preferred line, touching on drunken nights, bad decisions, whirlwind love, and regret, but in Stapleton’s hands, these subjects don’t feel worn. His voice infuses them with an emotional mastery that creates chills. — AW

Most Likely to Hasten the End of the World: David Rawlings, Poor David’s Almanack

David Rawlings’ third solo album is as sure a harbinger of the apocalypse as any other musical release of 2017. Not because it’s so bad (it’s actually very, very good), and not because it’s that good, either (it’s actually not oceans-boil-over good). It’s because you could buy it on vinyl the day it hit stores and digital outlets. Poor David’s Almanack is the first Acony album to get a simultaneous LP release, which brings to an end Rawlings and Gillian Welch’s nearly 20 years of agonizing over pressings and sound quality. I predicted a global plague would precede such an occasion, and I’m relieved to lose that particular bet. So give these songs a spin on the turntable, which is obviously where they belong. Almanack is an endlessly inventive and lively collection of new folk tunes that sound old, as though Rawlings hadn’t written them but had found them in the back of some old antique store in the middle of nowhere. And yet, just like the old LP technology experiencing its own resurgence, these old-sounding songs somehow sound current, relevant, prescient: “Money Is the Meat in the Coconut” pokes fun at some of our swamp-draining politicians, “Good God a Woman” slyly inverts gender politics, “Come On Over My House” turns class warfare into a randy come-on. Rawlings knows these issues have been driving civilization since before we invented fire, and it’ll continue to drive the last handful of humans staving off the hordes of zombies. — Stephen Deusner

Most Likely to Soundtrack Your Next Roadtrip to Who Knows Where: Hiss Golden Messenger, Hallelujah Anyhow

M.C. Taylor’s favored subjects are home and hearth, family and faith, yet his songs are as much about the lure of the road as the comforts of home. His latest as Hiss Golden Messenger, recorded in a matter of days in North Carolina, is a highway record, an album about being lost out in America in the Anthropocene Age and trying to navigate by moral compass. What do we owe other people, strangers, and loved ones, alike? What do we owe ourselves? On “I Am the Song” and “Harder Rain,” Taylor understands those questions don’t have concrete answers — that they change from one song to another, from one person to another, from one highway to another. But that doesn’t diminish the importance of posing those questions. Instead, the slipperiness of these ideas enlivens his music, which plays with rock and folk history without putting a record collection between Taylor and the listener. “Gulfport, You’ve Been on My Mind” slyly rewrites Bob Dylan, while Van Morrison goes through the wringer of “Domino (Time Will Tell).” Best — or at least, most unexpected — may be the shoutout to the gloriously ridiculous goth act Sisters of Mercy. In his responsibility to his heroes and to his listeners, Taylor finds joy and humility and the special fulfillment of a noble calling, especially when he can rebuke a certain leader of the free world: “What’cha gonna do when the wall comes down?” he asks, not at all rhetorically. “It was built by man, and you can tear it down, tear it down.” — SD

Most Likely to Make You Buy a Shruti Box: House and Land, House and Land

When Shirley Collins recorded “The False True Love” 50 years ago, she made it sound crisp and mournful, as if she were looking out over a frosty morning. You can see her breath hang in the air, and you can sense sorrows as heavy as the clouds. When Louise Henson and Sally Anne Morgan tackle the song on their debut as House and Land, it warms up only slightly, thanks to the interplay between guitar and banjo. It’s less lonely, but no less sorrowful. It sounds more existential, as though romantic woes might blot out their souls. So call House and Land a supergroup: Morgan plays with the Black Twig Pickers and Pelt, two Virginia string bands redefining roots and folk music away from the Americana set, and Henson may be one of the most compelling folk guitarists to pluck a string in 2017. They’ve been collecting songs for a few years now, and they’ve assembled them into an album that mixes banjo, guitar, and rustic drones from a Shruti box in some ways that are familiar and other ways that are entirely new. Just as they straddle folk and avant garde, the duo also contemplate the spiritual crises of this life and the next. Songs like “The Day Is Past and Gone” and “Home Over Yonder” examine faith and its celestial reward, depicting the afterlife as a lonely place. “There was nobody there to answer for me,” they lament on “Listen to the Roll.” “I had to answer for myself.” — SD

Best Fireside Chat: Iron & Wine, Beast Epic

Sam Beam has a stately way of drawing the listener close. Beast Epic, Beam’s sixth project as Iron & Wine, opens with his whispered count in on “Claim Your Ghost” before launching into the warm reverberations of “Thomas County Law,” which boasts poetic musings like, “Every traffic light is red when it tells the truth. The church bell isn’t kidding when it cries for you.” In fact, each track on Beast Epic is rendered with such startling care and intimacy that the listener may as well be sitting fireside with Beam. With lush acoustic arrangements bound by touches of percussion, piano, harp, and cello, Beam wields a gorgeous album brimming with some of the finest songwriting to come out of Iron & Wine’s 15-year trajectory. One highlight, “Bitter Truth,” is packed with hard pills to swallow from a narrator who’s looking in the rearview mirror: “Our missing pieces walk between us, when we were moving through the door. You called ‘em mine, I called ‘em yours.” Those “pieces fall in place” on the album’s pinnacle and lead single, “Call It Dreaming.” By returning to Iron & Wine’s stripped-down roots, Beam reminds us that power can come from the quietest corners. — DM

Most Masterful Finger-Pointing: Jason Isbell, The Nashville Sound

When you make what people universally agree is an absolute masterpiece of a record fairly early on in your career, how do you ever again pick up a pen? Well, if you’re Jason Isbell trying to follow up 2013’s Southeastern, you set an entirely different bar for yourself to clear … which he did, with 2015’s Something More Than Free, and which he has done again, with The Nashville Sound. While both are filled with common-man character studies and captivatingly personal confessionals, The Nashville Sound uses some of those tales to take on politics and privilege in beautiful, bold ways. In both “Hope the High Road” and “White Man’s World,” Isbell points a finger of blame, including one at himself, to show how all of us are accountable to ourselves and to each other. Thing is, as part of the same motion, he opens his hand and extends it to anyone willing to grab on. Hard to think of other songwriters who could accomplish that feat while also rocking their asses off. It’s also hard to think of other songwriters who can switch gears so effortlessly to write some of the most stunning love songs to ever exist. As with “Cover Me Up” and “Flagship” before it, “If We Were Vampires” takes on love, Isbell-style, by turning it inside out. Dave Cobb has used the word “devastating” to describe various songs and songwriters he’s produced. In Isbell’s case, it is very often an understatement. — Kelly McCartney

Most Likely To Flip The Script: Laura Marling, Semper Femina

Since releasing her debut in 2008 at the mere age of 17, UK folkie Laura Marling has garnered a reputation as a prolific artist and a deep thinker. Her knack for intricate guitar work and lyrical allegory has solidified her place among music’s greatest storytellers, and her latest album, Semper Femina, is a layered masterpiece that serves to further bolster her prolific body of work. Here, she works to subvert the male gaze, just as she did in an interview-based podcast exploring women’s experiences in the arts called Reversal of the Muse. Only, on Semper Femina, she does so by taking up the perspective often employed by men in artistic traditions — that is, by admiring and lusting after the women who serve as the album’s centerpiece. But that’s not to say that the album lacks introspection. The collection is just as much an effort for Marling to tap into her core self, as it is an exploration of how women are viewed and portrayed in society. Sonically, Marling’s signature fingerpicking and warm vocals remain, but this collection of songs reflects a marked growth from her previous output. By playing with percussion and making use of space, Marling gives her ideas room to breathe and expand. Whether through bits of spoken word on “Wild Once” or elegant falsetto on the album’s standout “Always This Way,” each song beckons you closer and is imparted like a secret that you’re lucky to be in on. — DM

Most Likely to Soothe and Summon the Spirit of George Jones: Lee Ann Womack, The Lonely, the Lonesome, & the Gone

Lee Ann Womack could win awards for her song selection alone: Throughout the course of her career, she’s sniffed out some of the finest scribes in country music and put tracks by Brent Cobb and Chris Stapleton on her records far before the rest of the world caught on to their powers. Like Linda Ronstadt and George Strait, it was the potent combination of her legendary vocal abilities and her nose for talent that left us with jewels like her 2000 hit, “I Hope You Dance.” Which is why it was surprising to see her own name listed in the credits more than ever on The Lonely, the Lonesome, & the Gone, a personal progression of a record that proves her pen is as mighty as her vocal sword. There’s a touch of mystery and melancholy across the songs of The Lonely, the Lonesome, & the Gone — from the gorgeous balladry of the title track to the simple plucks of “End of the End of the World” where Womack’s twang churns out on glorious full display. Produced by her husband, Frank Liddell, and recorded at Houston’s Sugar Hill Studios, the album lets Womack walk through classics old (a version of “Long Black Veil,” made iconic by Lefty Frizell, that is most welcome) and new (the album opener “All the Trouble,” which is a moody, gospel tour through her stunning range). It’s thrilling to see an artist this deep into her career prove that she still has treasure trove of surprises up her sleeve. — MM

Most Likely to Have Hats Actually Made in the USA: Margo Price, All American Made

On her debut LP, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, East Nashville’s Margo Price became one of country and Americana’s breakout stars with her honest-to-the-core songwriting that was never afraid of being uncomfortable. She spoke of devastating loss, disappointment, and being done wrong in one of the most revealing, personal albums in years. For her follow-up, All American Made, Price looks outward, surveying the world outside her tour bus window to tackle everything from wage inequality to the plight of rural America, brazenly using her voice to drive conversation in an increasingly perilous political environment. “No one moves away with no money. They just do what they can,” she sings on “Heart of America.” “To live in the heart of America, getting by on their own two hands.” Recorded at Sam Phillips in Memphis, Price weaves everything from gospel to R&B and honky-tonk into the songs, often co-written with her husband Jeremy Ivey, coming out with an album that captures the urgency of late ’60s protest anthems but with heaps of Tennessee soul. With one stellar duet partner, Willie Nelson, on “Learning to Lose” and help from the McCrary Sisters, Price bends and twists the shape of the genre into her own rock band-rooted form, centered around a dynamite set of pipes that can belt, howl, and softly whisper through whatever lies ahead of her. “Wild women don’t worry,” she sings … and Price doesn’t. Like Woody Guthrie, she’s a prophet of the people, not the establishment. — MM

Best Call to Order, Not Arms: Mavis Staples, If All I Was Was Black

Who could’ve known that pairing gospel/soul legend Mavis Staples with alt-country anchor Jeff Tweedy would be darn near perfect? On If All I Was Was Black, Tweedy’s production provides a wonderful warmth and gorgeous grit to match Mavis’s iconic voice. While last year’s Livin’ on a High Note showed Mavis off in all her feisty, funky glory, If All I Was Was Black turns that down a notch to make room for a more heart-centered approach. After all she’s witnessed in her life, Mavis somehow manages to hold fast to hope and continue pleading for peace. If she’s angry about the two-steps-forward-three-steps-back phenomenon currently overtaking the world, you would never know it from listening to her records. Now, that’s not to say Mavis doesn’t see the problems we face. She does. She always has. It’s just that she would prefer we muster all the love we possibly can, and use that to fuel our fire rather than rage. The compassion and patience embedded within “We Go High” — sparked by Michelle Obama’s comment of “When they go low, we go high” — is almost unimaginable in light of the utter cruelty and devastation being heaped upon marginalized populations in 2017. But there it is. Songs like “No Time for Crying” and “Build a Bridge” also lay it out in the clearest of terms. And, with the title track, she calls out the problem of judging people by their skin and not their hearts, as doing so causes us to miss the beauty and goodness that each of us has to offer. All through this album, Mavis implores us to let our better angels be our guides. What she may not understand is that she, herself, is our better angel. — KMc

Most Likely to Carry around a Battered Copy of My Side of the Mountain: Mipso, Coming Down the Mountain

Mipso find themselves at a moment in their lifespan when a rootsy band discovers that a bluegrass-driven aesthetic is no longer quite enough to channel all of their creativity and curiosity. (See: Nickel Creek, Sierra Hull, Mandolin Orange, etc.) But as they fully incorporate drums, electric bass, and guitar into their sound, they aren’t walking directly away from the North Carolinian acoustic traditions that have informed them all the way. This refining of their folk-rooted, definitively Americana sound refutes the idea that doing so means relinquishing the raw authenticity of bluegrass and old-time, by default. On the contrary, Mipso’s finesse allows the more subtle aspects of their constituent influences to shine through on Coming Down the Mountain, undaunted by the “electric” embellishments. The title track epitomizes this down-to-earth sheen with tales of fishing, disdain for the fools of the city, and pictures of rhododendron thickets in the mountain hollers, all dressed up in dreamy, effervescent duds. There’s honky-tonking, California vibes, train whimsy, sad ballads, haunting alt-folk, and much more woven into this record and these songs. With the love and care they’ve invested in its creation, it hits you like a beautiful kaleidoscope, rather than the dull brown of every color of paint combined willy-nilly. If the current commodification of “roots” music has sent you running for the hills, looking for a refuge and a respite, Coming Down the Mountain might just compel you to hang up your fishing pole for a while and come back to the city, even if for only 10 songs. — JH

Best Reminder to Bake Right with Hot Rise: Molly Tuttle, Rise

On the surface, it feels like 2017 was Molly Tuttle’s breakout year. In a matter of months, she went from releasing her debut LP, Rise, to winning the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Guitar Player of the Year award — becoming the first woman in the organization’s history to ever receive the honor. But her poetic, evocative lyrics and her confident, firecracker flatpicking are unmistakable markers of what really has been a life-long career. The firm foundation laid by growing up in bluegrass, performing and touring from a young age, shines through each and every track on the record, assuaging the fears of would-be naysayers who could find the occurrences of lap steel, full drum kit, or electric guitar to be bluegrass disqualifiers. Her haunting vocals, at once ethereal and authoritative, are utterly confident, each artistic choice precise without falling into measured sterility. The distinct voice of Rise — whether emanating from Tuttle’s lips or her pick and strings — isn’t first-timer’s luck; it’s the product of a lifetime of work and expertly honed talent that is simply, at long last, reaching the ears of a broader audience. And, where other burgeoning artists may falter in their first few projects, attempting to pinpoint the perfect vehicle for their artistic personalities, we can sense, feel, and hear that no matter which stylistic direction she may take in the future, we will all be watching Molly Tuttle rise, unencumbered and unwavering. — JH

Most Heartfelt Look at the Heartland: Natalie Hemby, Puxico

Sometimes records sound exactly like you want them to: The songs, the singer, the production … everything just fits and flows. That’s Natalie Hemby‘s Puxico. Equal parts front-porch folk and heartland rock, this album was inspired by the small Missouri town where Hemby spent her childhood summers fishing with her grandpa George and dancing at the annual Homecoming. And it’s infused with the songwriting skill of Nashville where Hemby honed her craft writing cuts for Miranda Lambert, Lee Ann Womack, Maren Morris, Johnnyswim, and others. With Puxico, though, Hemby writes closer to home, metaphorically and musically. No commercial country artist like so many of her friends, Hemby is cut from the Sheryl Crow cloth (with some Tom Petty patches, to be sure). Her voice is warm and soulful, powerful and edgy, all at once. And the songs … the SONGS. From “Time Honored Tradition” to “Cairo, IL” to “This Town Still Talks About You,” the songs are rich with remembrances of lives, loves, and losses. Hemby’s deep, deep fondness for the people and places of her youth is filtered through the lens of time and distance, allowing her to trace the edges of what was and overlay that image upon what still is. The space between the two is where these songs live. — KMc

Best “Year of the Banjo” Brand Ambassador: Noam Pikelny, Universal Favorite

Punch Brothers’ co-founder Noam Pikelny takes “solo record” to another level, playing every instrument on his fourth LP, Universal Favorite. He even sets down the banjo a few times to try his hand at electric guitar — turns out he’s ridiculously good at everything he touches. And would you believe it … he can sing, too! Pikelny’s PB bandmate and frequent producer Gabe Witcher keeps a tight rein on the record’s crystal clear sound, but gives his friend plenty of room to explore and expand his musical horizons. While the songs range from trad/old-time to classical sounds, and include covers from the likes of Elliot Smith (“Bye”), Josh Ritter (“Folk Bloodbath”), Roger Miller (“I’ve Been a Long Time Leavin’ (But I’ll Be a Long Time Gone)”), amongst others, the virtuosic solitude that pervades this fully unaccompanied project allows the whole thing to feel cohesive, complete, and brilliant. — Amy Reitnouer

Most Likely to Not Give Any Fucks: Rachel Baiman, Shame

With the co-founding of Folk Fights Back in Nashville and the release of her second solo album, Rachel Baiman has earned a reputation as a radicalized bluegrass player, although neither of those labels is exactly apt. Her background is in bluegrass, and she’s a dexterous and sensitive fiddler, but that particular musical style is merely a foundation on which she builds songs informed by pop and folk and country, by Gillian Welch and John Hartford and Phil Ochs. And she barely even plays the fiddle on here, instead switching between banjo and acoustic guitar. As for politics, she tackles that topic only because she recognizes that it’s unavoidable. Being a woman and being an artist have become fundamentally radical activity in late-2010s America, which means Baiman is simply following Woody Guthrie’s old adage: “All you can write is what you know.” She knows touring, for instance, and turns that into the rousing “Never Tire of the Road.” She knows about writing songs and writes a song about writing songs, the sing-along “Getting Ready to Start (Getting Ready).” And she knows about old white men using religion as a bludgeon, and she not only makes that the central idea of the title track, but delivers the chorus with a steely defiance: “They wanna bring me shame. Well, there ain’t no shame.” On Shame, she sounds like the voice we need to hear right now, in roots or any other genre. — SD

Most Likely To Break Free: Ryan Adams, Prisoner

A case can be made that love and sex are the backbone of music, so it naturally follows that the other side of the coin carries equal weight. For every song written about relationships or lust, there’s one about the counter moment when everything comes crashing down. Ryan Adams is one of those artists who’s no stranger to the nuances of dissolution. After all, the North Carolina singer/songwriter made his solo debut outside of Whiskeytown in 2000 with a sweeping masterpiece dubbed Heartbreaker. Widely regarded as his best work, Heartbreaker received a deluxe reissue last year while this year saw the release of a companion album of sorts in Prisoner. Written as a means of salvation during Adams’ highly publicized divorce from actress/singer Mandy Moore, Prisoner is a foray into loneliness that embraces the post-breakup fallout headfirst. The mid-album stunner, “To Be Without You,” is a portrait of perfect songwriting that smoothly unfurls amidst lines like “It’s so hard not to call you. Thunder’s in my bones out in the streets where I first saw you. When everything was new and colorful, it’s gotten darker.” That just stings with familiarity. Elsewhere, “Broken Anyway” is a mature attempt at shaking off the remains: “What was whatever it became? Whatever, we will still be together in some way. It was broken anyway,” sung by a narrator who acknowledges the pains of both inflicting and falling victim to heartbreak. Crafted with Adams’ penchant for the sonic flair of the ‘80s, Prisoner toils in the confines of human emotion and comes out triumphantly on the other side. — DM

Best Trip through the Bluegrass State’s Bardo: Tyler Childers, Purgatory

It can be difficult to stand up to Kentucky’s esteemed history of songwriters and performers — which includes everyone from the legendary Bill Monroe to Sturgill Simpson — but Tyler Childers lives up the legacy of his home state with as keen an eye for its past as for its future. On Purgatory, produced by Simpson and one-time Johnny Cash engineer David Ferguson, Childers emerges with a voice that can cut with the innocence of a child but the knowledge of an aged man and an eye for painting stories of people shaping their identities in small towns and searching for love amongst the ruins. In Childers’ hands, modern roots music can meld into some rock ‘n’ roll fury (“Whitehouse Road,” “Universal Sound”) or striking, chill-inducing romantic opuses like “Lady May,” always centered on those spectacular vocals and an uncannily creative lyrical sense: When he sings “get me higher than the grocery bill” on “Whitehouse Road,” he manages to rouse images of intoxication and the desolation of a segment of America where a simple trip to the grocery store can be a financial burden. Melding the bluegrass roots of his home state with Simpson’s abandonment of genre altogether, Purgatory is a coming of age record for everyone grasping at the space between shelter and freedom, between freedom and commitment to another, between commitment and the fragile promise of eternal love. — MM

Best Musical Evidence That Black Girl Magic Is Real: Valerie June, The Order of Time

Valerie June is an other-worldly artist with a seemingly cosmic connection to her muse. Her songs are full of whimsy, wonder, and wisdom, all grounded in a garden of earthly musical delights. Blues, folk, gospel, soul, country, and more all sneak into June’s work, colliding in a kaleidoscope of sounds and colors. Sputtering guitars bump into stuttering keys on one song, while ethereal strings ebb under ambient steel on another. Harmonium and horns?! Hell yeah. African rhythms and clawhammer banjo?! Ya damn right! She’s from the melting pot of music — Memphis, Tennessee — after all. Nobody else is making music like this. Listening to June’s records feels almost intrusive, as if peering into a private diary filled with poems and doodles that betray the artist’s inner world in its utterly pure, stream of consciousness form. Except that The Order of Time is more refined and restrained than that. Such is this album’s perfection, that it would be a fool’s errand to attempt choosing standout tracks. The booty groove of “Shakedown” or the gentle drone of “If And”? The mystical dance of “Astral Plane” or the bluesy sway of “Love You Once Made”? Not even Sophie could make that choice. Nor should she — or we — ever have to. — KMc

Best Open Diary: The Weather Station, The Weather Station

If other songwriters fight to fit their words within a song’s measure, Tamara Lindeman takes the opposite tactic as the Weather Station. Her verbose songs are chock full of words — their inflections adding rhythmic scope, their syntax unraveling deeply personal confessions. “I don’t know what to say, so I say too much,” she sings on “I Don’t Know What to Say.” Somehow, though, Lindeman keeps her music from feeling overcrowded. Her vocal cadence works in tandem with rhythm guitar (as on “Thirty”) or drums (as on “Complicit”) to reinforce a singular meter rather than stuff each song to the brim. With her self-titled album, she told the BGS that she focused on “figur[ing] out how to be okay when things are not okay.” A central relationship thrums at the album’s center, filling her with all manner of declarations. Lindeman is, at turns, self-deprecating (“My love is the heaviest thing” on “Keep It All to Myself”), regretful (“We never figured out the questions” on “You and I”), and adamant (“I guess I always wanted the impossible” on “Impossible”). But the album’s most devastating addition takes place at the close with “The Most Dangerous Thing About You.” It’s quiet for an album charging forward, either lyrically or rhythmically, and focuses on the aftermath of what she has spent the previous 10 tracks parsing out. For all the communicating Lindeman does on The Weather Station, words don’t offer a magical resolution, but there’s something fiercely beautiful about the effort to keep searching. — AW