(Editor’s Note: This story was first published in November 2023 by our friends at Roots Radio WMOT 89.5. Visit their website to hear the best in listener-powered independent American roots music and to read more by journalist and producer Craig Havighurst.)

Sixty years ago, an 18-year-old David Grisman made his way to a place called the Coral Bar in West Paterson, New Jersey. He brought with him a portable Wollensak reel-to-reel tape recorder and a good measure of youthful chutzpah. He found the dressing room of his quarry – bluegrass stars the Osborne Brothers – and asked Sonny and Bobby if it would be okay if he recorded their show that night.

“And Sonny Osborne looked at me and said, ‘You can record the show. But if that ever comes out on a record, I’ll find you and I’ll kill you.’”

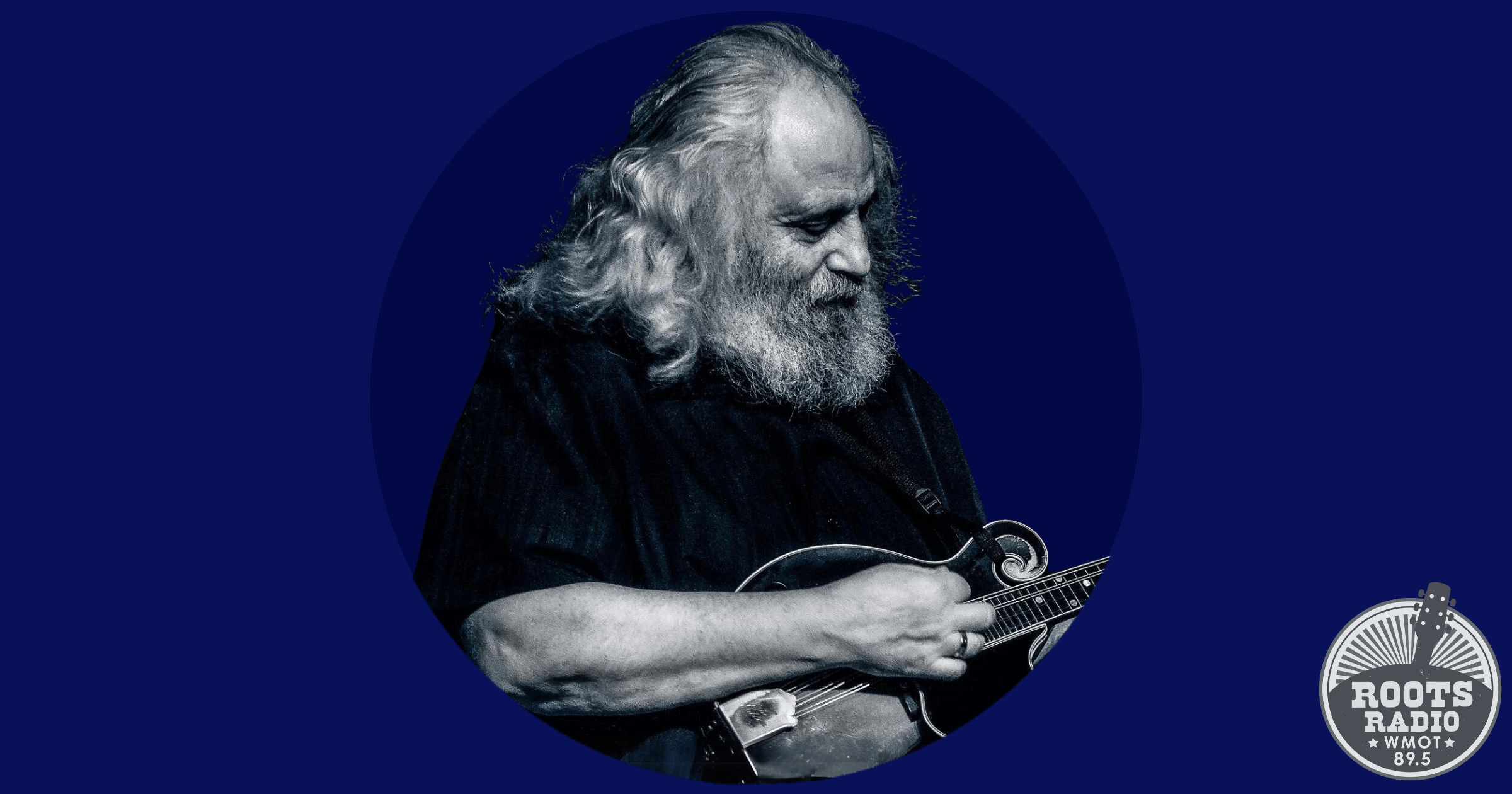

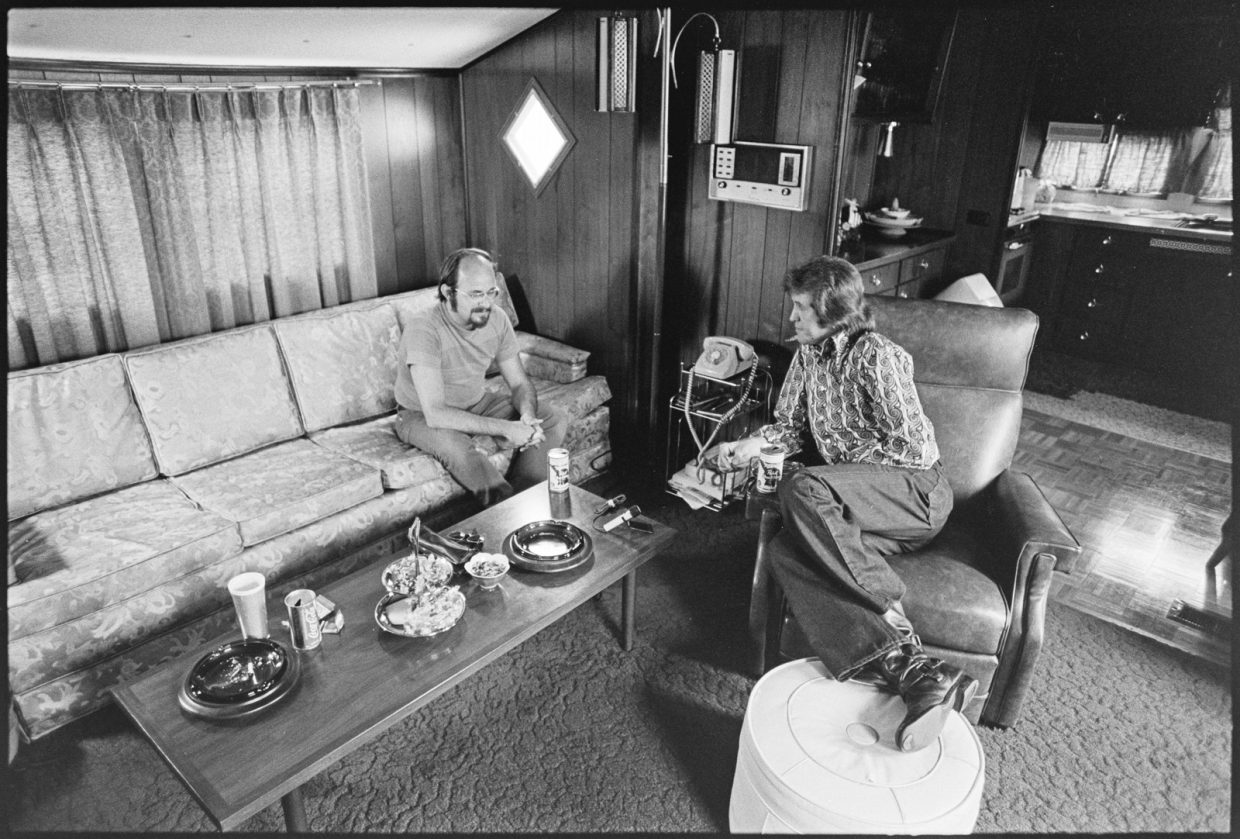

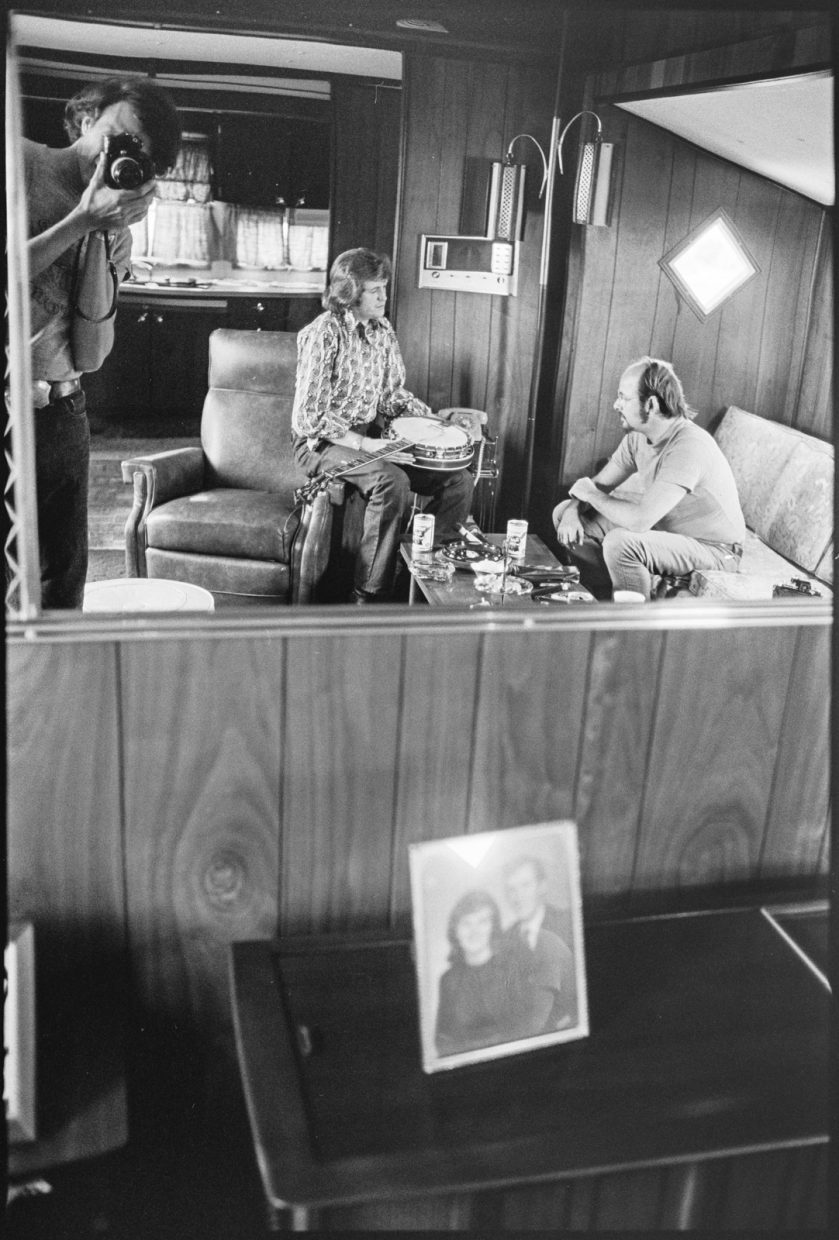

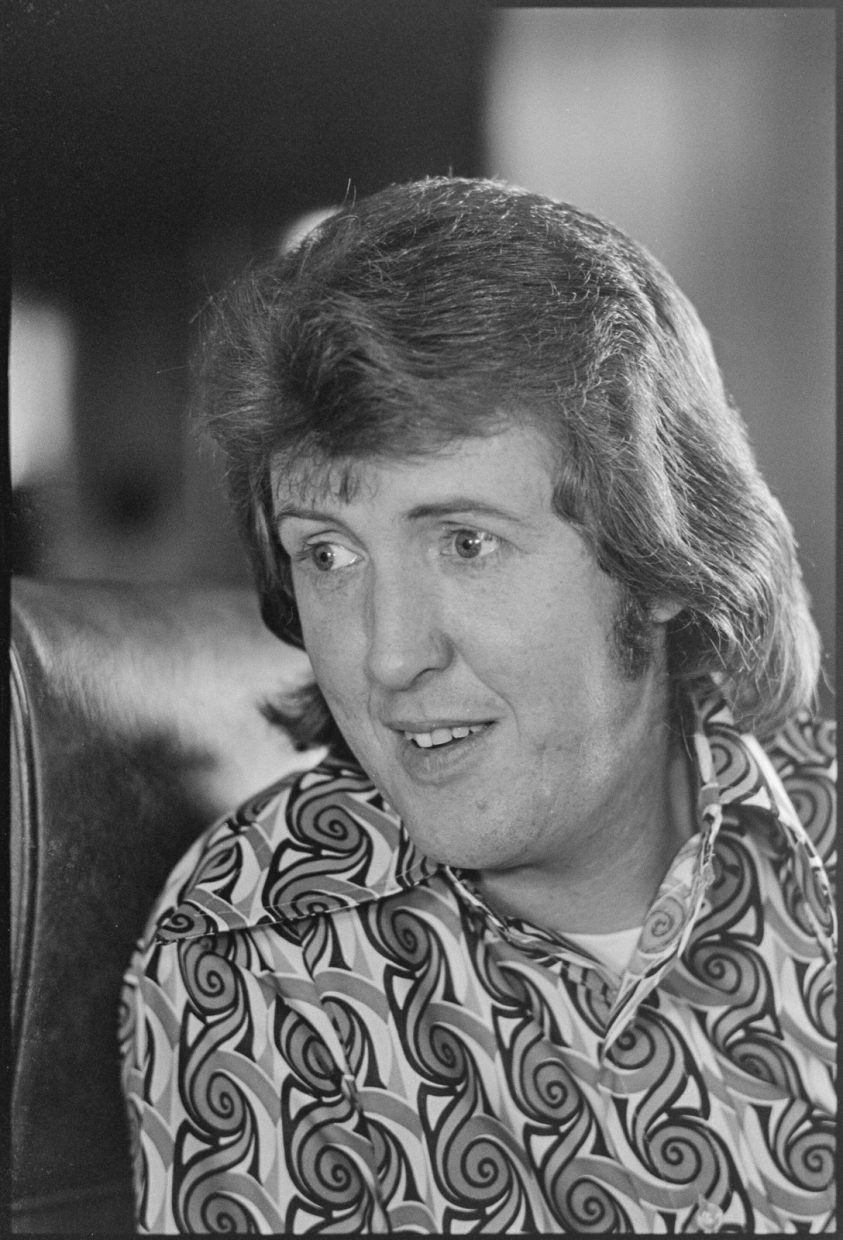

Grisman, now 78, recounts this memory at his home in Port Townsend, Washington. It’s a turn-of-the-20th century house with high ceilings, period furnishings and beguiling, music-themed paintings on the wall by David’s wife Tracy Bigelow Grisman. I got to visit the master mandolinist this summer, just weeks before he was announced as one of 2023’s inductees into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame, an honor that was consummated in late September during the IBMA Awards.

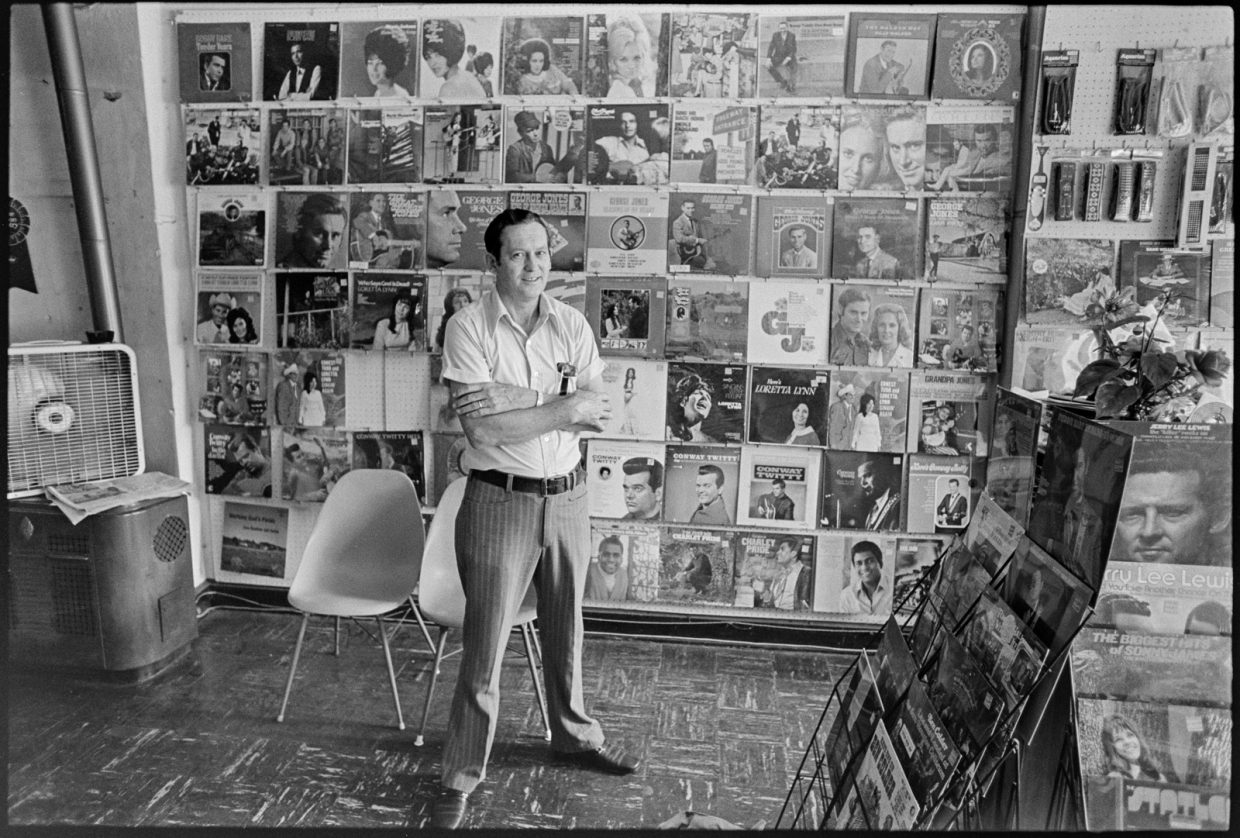

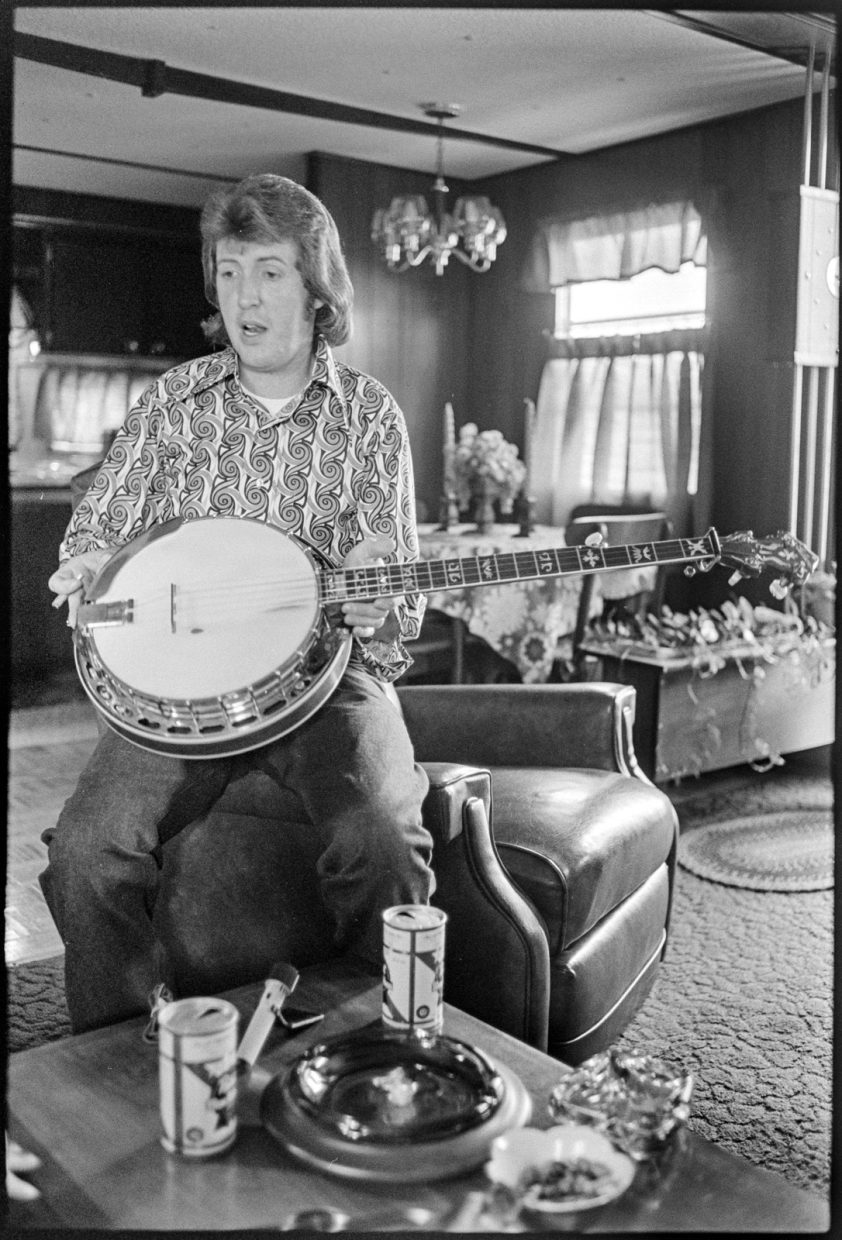

While he was hailed by the bluegrass establishment for his “distinctive and influential” mandolin playing, his visionary advances in string band music, and the creation and cultivation of an offshoot of bluegrass so particular that Jerry Garcia dubbed it “Dawg Music,” Grisman’s legacy also includes a lifelong passion for recording acoustic music. Taking cues from his mentor, the folklorist Ralph Rinzler, Grisman has captured live shows, friendly jams, and studio sessions across six decades. Many of his best tapes have been released since 1990 on his own record label, Acoustic Disc.

Artist-owned labels are rare enough in their own right, but there may never have been a label that documented an artist’s own influences and output across time as abundantly as Acoustic Disc does for Grisman. He’s reissued historic music that touched him, including that of mandolinist Dave Apollon and Argentine jazz guitarist Oscar Alemán. He’s documented his personal mandolin heroes and pals like Jethro Burns and Frank Wakefield. But at its core, Acoustic Disc is a catalog of Grisman’s various collaborations, as leader of his David Grisman Quintet, in his influential bluegrass supergroup Old and In The Way, and in duos with Jerry Garcia, Del McCoury, Andy Statman, Tony Rice, and Doc Watson.

For several decades Grisman partnered in the label with longtime friends Harriet and Artie Rose, but in 2020 he and Tracy acquired full ownership and took it all digital, which Grisman says “has allowed me to triple my production of new releases.” The newest, out last week, is a 50th Anniversary Edition of Old & in the Way Live at Sonoma State, recorded in November of 1973. That follows on a recent digital release of an informal 1976 session that Grisman calls the New Smokey Grass Boys with Darol Anger on fiddle, Tony Rice on guitar, Todd Phillips on bass and Robert Bowden on banjo. Also recent, the six-volume collection Dawg Works covering all of Grisman’s instrumental compositions recorded with a who’s who of acoustic and bluegrass pickers.

Acoustic Disc (encompassing the legacy CD releases in physical and digital form) and its sister label Acoustic Oasis (all download) offer a thread of immersive snapshots from the life of a man who seemed to be everywhere that mattered in bluegrass from the early 1960s into the 21st century. And we might not have this rich portrait of Grisman’s influential career if fortune hadn’t brought him early on into the world of renowned folklorist, artist manager, and promoter Ralph Rinzler as he grew up in Passaic, New Jersey.

“I was really into early rock and roll. You know, Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis,” Grisman said. “It was being born really. And so I was one of those young, impressionable kids. But around 1958 or ‘59 it started evaporating. Buddy Holly got killed, you know? Little Richard got either busted or became religious. Elvis went to the Army. And pop music got very vapid.”

Into the vapid void came folk music, first the polite kind like the Kingston Trio but soon this rougher, richer sound called bluegrass began to reach teenaged Grisman. He and some friends formed a folk music club at his high school, and the cousin of his favorite teacher came to talk and demonstrate records and instruments. That was Ralph Rinzler, and the encounter changed Grisman’s life. Rinzler, 10 years older, hosted late night listening sessions at his home, which happened to be four blocks away, sharing music by Jimmy Martin and the Stanley Brothers, until Grisman’s mother telephoned to call her son home.

In 1961, Rinzler invited Grisman along on a road trip to the New River Ranch for an outdoor show with Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys and another blazing mandolinist named Frank Wakefield. “There was a small backstage. I heard them play mandolin duets,” Grisman said. “And that really blew my mind. The whole experience blew my mind.”

In Rinzler, Grisman had latched onto a key figure in American folk music. He was a mandolinist with the popular Greenbriar Boys at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village. He’d go on to manage Monroe and Doc Watson, promote many shows, and run the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and Folklife Program. His passion as an archivist rubbed off.

“I got this all from Ralph, you know? He was going on these field trips, finding these musicians and recording them,” Grisman says of their early years together. “For a while, Ralph lent me his Nagra, the premier portable Swiss tape machine. I made a tape of Jesse McReynolds and Bobby Osborne playing duets in a shed outside a show in Maryland in 1965 that I still have.”

So Grisman was thinking like a producer by the time he started at New York University in Greenwich Village, and at age 18 he officially became one. First he took a recorder to Wakefield’s Hyattsville, Marylad home where he captured an informal jam session with great songwriting bluegrass star Red Allen. His young partner on that trip Peter K. Siegel, another acolyte of the music, worked with Grisman to gather the personnel and repertoire for the album Bluegrass by Allen, Wakefield and the Kentuckians on Folkways Records in 1964. The jam tape, which Grisman used as a practice guide for his own mandolin playing, was released by Acoustic Disc on CD and download as The Kitchen Tapes.

Grisman produced two more Red Allen albums and played in his band for a bit before the next major shift in his life, one that reflected the times. In 1967, he conspired with fellow bluegrasser Peter Rowan to go electric with the psychedelic folk-rock band Earth Opera. They made two albums for Elektra before disbanding, and by 1970, Grisman had moved to the Bay Area, where he’d spend most of his life. A fellow he’d met back east in ‘64 or so was out there making quite a name for himself in rock and roll, but Grisman knew that Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia’s first instrument was banjo and that he was good at it. That led to the first project that truly set Grisman apart as one of the great influencers of bluegrass music.

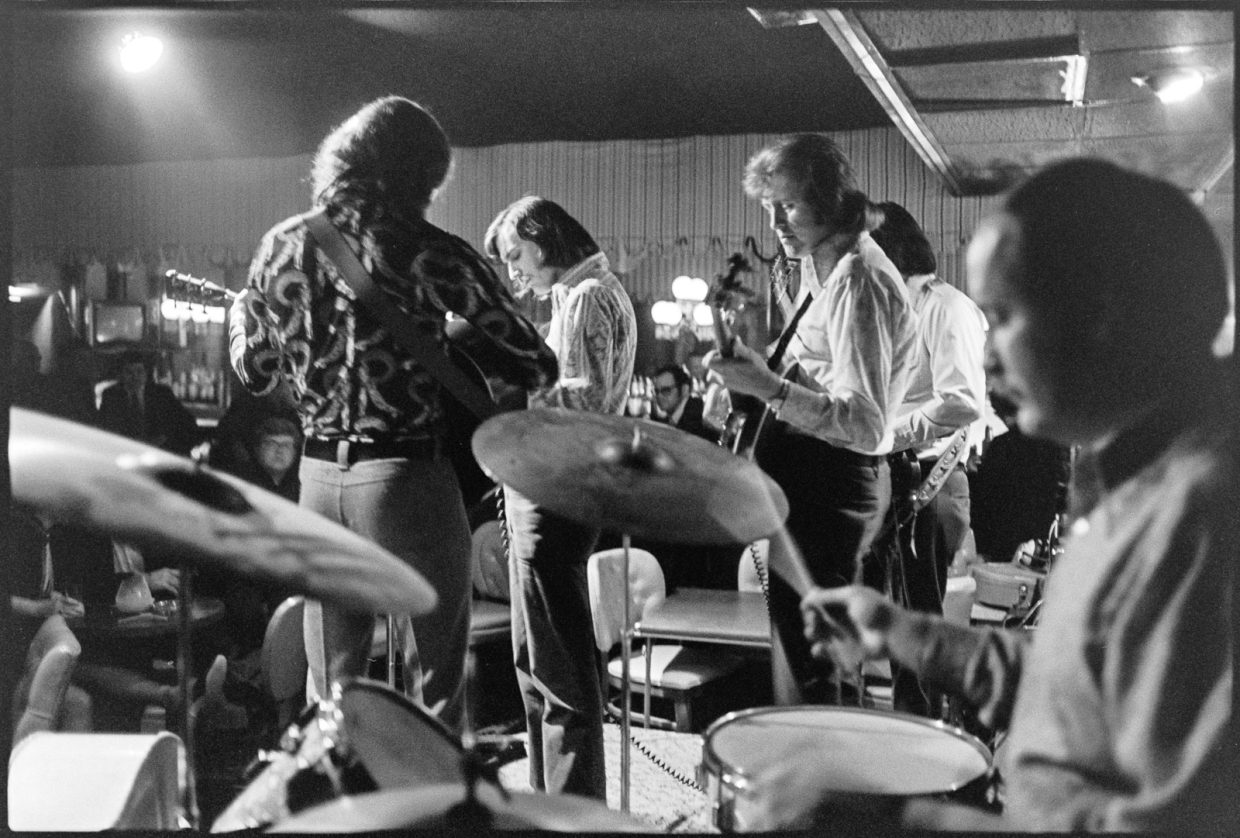

It wasn’t Grisman’s tape recorder that was running on October first and eighth of 1973 at the Boarding House in San Francisco, but Owsley “Bear” Stanley knew what he was doing as sound engineer for the Grateful Dead. Grisman was on stage with Garcia on banjo, Peter Rowan on guitar, Vassar Clements on fiddle and John Kahn on bass. The set lists blended classic repertoire with Rowan originals like “Panama Red” and “Midnight Moonlight” that would become standards.

Ten tracks from those two live sets were put out in 1975 on the Dead’s in-house record label as Old And In The Way, which became by some reckonings the best-selling bluegrass album of all time. With its reach from rock and roll through the songwriting sensibility personified by Rowan and the daring improvisation of Vassar Clements, it was certainly among the most influential. Grisman released both shows in their entirety for the first time as Live At The Boarding House – The Complete Shows in high definition digital download. It’s an extraordinary time capsule of a pivotal confluence in roots music.

The Mill Valley, California house where Grisman settled became a hub for musicians where the mandolinist got to work out the sound and approach he’d been thinking about for years, one grounded in the sounds of stringed instruments working together more than the high lonesome singing of traditional bluegrass music.

“At some point early on, we realized that we could play instrumentals if we made it interesting enough,” said Grisman about a stretch in a band with the innovative fiddler Richard Greene. “And so we would do ‘Lonesome Moonlight Waltz’ (by Monroe). We’d do a Duke Ellington tune. We’d do Django (Reinhardt) and Stéphane Grappelli tunes. We started mixing it up. And then I guess I always had this composer in me. And as soon as I had this outlet for it, I had a list of tunes.”

Original tunes and another reel-to-reel tape recorder played a role in bringing Grisman together with Tony Rice, an early ’70s hotshot bluegrass guitarist whose Kentucky tutelage with traditional band J.D. Crowe & the New South was coming to an end.

“I had put together an album of the music I had written – all these tunes that I later did with my first quintet. And I had this tape with me. And Tony wanted to hear it and we’re in this living room filled with people,” is how Grisman remembers their first encounter. So instead, they did some picking, and Grisman was astonished, overwhelmed with memories of the master flatpicker Clarence White, who had recently been killed by a drunk driver. (“I figured I’d never hear that (style) again,” he said.) Eventually, Grisman was able to play his recorded music for Rice. “I put the tape on,” said Grisman. “And he listened to it and said, ‘I’d give my left nut to play that music.’”

That extreme sacrifice wouldn’t be necessary. A short time later, Rice had decamped for the Bay Area and joined what became the David Grisman Quintet with Todd Phillips on second mandolin and a young Bay Area fiddler named Darol Anger (now a Nashvillian). Soon, the great Mike Marshall took over the second mando seat with Phillips shifting to bass, where he’d have an outstanding career. With this, Dawg Music really took off, with its fusion of bluegrass, gypsy jazz, and classic swing. It was all instrumental, with all the architecture and improvisational freedom of a jazz band, played on bluegrass instruments, propelled by a fierce sense of timing and dynamics. Acoustic Disc offers a triple-length, 20-year retrospective DGQ compilation and a 1979 live show at the Great American Music Hall.

Also in that decade, Grisman decided to build a studio in his home, a rarity at the time. A San Francisco recording studio he’d worked at was closing down and he was able to make a deal for the recording console and tape machine, opening up the prospect for sessions that could be spontaneous and unbounded by budget. The most historic of them might be his duo recordings with Jerry Garcia. The two had been out of touch for about a decade when Garcia sponsored Grisman for an artist grant from the Dead’s foundation, which prompted a call and a get together.

“(Jerry) walked in the door, and he said, I know what we should do. We should make a record. And so I said, Wow, I just started a record company, and I have a studio in the basement. He said, Great, we’ll do it for you. And we walked downstairs. And I put two microphones up, and I still have the tape of what we played for the first time,” Grisman said. “Anyhow, it’s just been kind of serendipitous like that. And then we did over 40 sessions for the next five years until he passed away.”

The seminal release in 1991 was simply called Garcia Grisman, with vocal/instrumental arrangements including the blues standard “The Thrill is Gone,” Irving Berlin’s “Russian Lullaby,” and an acoustic “Friend of the Devil.” Like Old And In The Way, this album circulated like mad among open-minded bluegrass and roots aficionados who adored its mellow swing, its fascinating repertoire, and the chance to hear Jerry Garcia play acoustic guitar in a manner so different from the Dead. They also released a jazz forward album called So What and an ostensible children’s album called Not For Kids Only that became, according to Grisman, his label’s all-time best-seller.

In early 1993, Tony Rice spent a few days at Grisman’s home making an album that tapped those masters’ love of great vintage instruments. Tone Poems featured 17 instrumentals, each with a pairing of guitars and mandolins made between the 1890s to the 1990s. (Acoustic Disc offers an expanded edition.) And what else to do in the evenings but invite Jerry Garcia over to meet and pick with Tony Rice? Recordings from those picking parties circulated among bluegrass nuts for years as bootlegs but were finally released formally as The Pizza Tapes, and Acoustic Disc offers the complete recordings as a 170-minute download. Other iconic duo sessions paired Grisman with Doc Watson (Doc And Dawg was another guidepost album for me and others) and Grisman with Del McCoury.

Grisman moved from California to a small seaside town on the Olympic Peninsula about a decade ago, but he still has a studio where Dawg magic happens. One recent project with implications for Grisman’s family legacy is the Dawg Trio with dissident banjo player and songwriter Danny Barnes (also now a Puget Sound resident) and Grisman’s son Sam on bass. Their collection Plays Tunes & Sings Songs is a multi-generational romp that shows the grooving power of Sam, who has his own Sam Grisman Project, a band that’s touring with a mix of original music and Dawg meets Dead repertoire.

While Grisman avows that he’s never been a Grateful Dead fan per se, being generally uninterested in electrified music, he’ll forever be part of the Dead’s story and reach because of his relationship with Garcia. As such, Grisman will play a key role in the upcoming exhibit Jerry Garcia: A Bluegrass Journey, which opens in March of 2024 in Owensboro, Kentucky. It will tell the story of Garcia’s acoustic roots, including Old and In The Way and the Grisman/Garcia sessions, establishing what a historic relationship it was.

Speaking of museum-worthy stuff, Grisman told me that he donated most of his studio multi-track masters to the Southern Folklife Collection at UNC Chapel Hill a while ago. The rest of the archive lives in his climate-controlled studio, where he works with Tracy and a small team to produce releases for Acoustic Disc and Acoustic Oasis. The growing collection assures us that Grisman’s diverse musical legacy will be available in perpetuity. They’re even talking about releasing that Osborne Brothers bootleg tape from 1963 – with permission of course.

(Editor’s Note: Read more writing by Craig Havighurst and listen to The String at WMOT.org)

Craig Havighurst is WMOT’s editorial director and host of The String, a weekly interview show airing on WMOT 89.5 Mondays at 8 pm, repeating Sundays at 7 am. He also co-hosts The Old Fashioned on Saturdays at 9 am and Tuesdays at 8 pm. Havighurst has been a regular contributor to BGS over the past decade.

Photo Credit: Eric Frommer