It’s summer, our second in the “after times,” where road trips, national parks, and scenic byways are king. As you head off on your COVID-aware vacations this summer, don’t leave all the driving music to indie, easy listening, country & western, or rock ‘n’ roll. The chop of the mandolin, thump of the doghouse bass, and rapid-fire roll of the five-string banjo are just as suited to soundtrack your sunny forays. To prove that point, here are 16 bluegrass songs perfect for inclusion on your summer vacation playlists. (Listen to the full playlist on Spotify below.)

“Highway” – Claire Lynch

Bluegrass being an itinerant livelihood and a nomadic community, traveling songs are just as expected a feature as murder ballads, train tunes (a form of travel song unto themselves!), and moonshine running tales. This modern classic via Claire Lynch — written by Lynch and Irene Kelley — is a perfect example of the form, more ‘90s country offered by a string band than a traditional, four-on-the-F-style grassy track. It’s delightful — and perfectly winsome and longing when you find yourself listening while traveling down the highway.

“Handsome Molly” – Tim O’Brien

Our July 2021 Artist of the Month Tim O’Brien’s rendition of this bluegrass classic is a far cry from, say, a Flatt & Scruggs’ cut. O’Brien’s has a slight transatlantic bent — with a distinct island detour, perhaps through the sunny Caribbean. If you’ve found a craving to set your foot on a steamboat and sail the ocean ‘round deep inside your soul, this one’s for you.

“1952 Vincent Black Lightning” – Del McCoury Band

Another track with a transatlantic story, this ever-popular, most-requested number covered by the Del McCoury Band is a road trip staple — whether you get in or on your vehicle to hit the highway. It would be a sin to make a bluegrass summer vacation playlist and not include “1952 Vincent Black Lightning!”

“Val’s Cabin” – Laurie Lewis

A rare example of a bluegrass song actually about summer vacations, this Laurie Lewis original, “Val’s Cabin,” begins as a simple retelling of childhood memories — nostalgia being a common rhetorical device (and when attempted by many other writers, a well-worn trope) in bluegrass. But Lewis, a veteran through-hiker, wilderness excursioner, and backpacker as well as a Grammy-nominated bluegrass singer and songwriter, tinges the story with melancholy and the existential questions raised by the ever-worsening climate crisis. The song is as evocative as it is gorgeous; though the singer can’t find the way to “Val’s Cabin” any longer, every listener can.

“Paddy on the Turnpike” – Vassar Clements

If you ever happen to find yourself Crossing the Catskills on a summery jaunt, “Paddy on the Turnpike” must be in your listening rotation. Avoid the tolls, but still go for a ride on the turnpike with Vassar Clements’ wild, unpredictable, jaw-dropping, wonky fiddling. “Paddy” is a blank canvas for Clements and a study in bluegrass’ unending affinity for flat seven chords.

“Don’t Give Your Heart to a Rambler” – Tony Rice

A hit in nearly every jam circle that ever circled, “Don’t Give Your Heart to a Rambler” is almost as if “Gentle on My Mind” had been written by a much less kind or compassionate protagonist. Tony’s solo vocal stylings are as iconic as his six-string licks, nearly obliterating any memory of this song ever having been sung by anyone else. What’s more, the titular advice of the track still stands. Just don’t.

“Highway 40 Blues” – Larry Cordle & Lonesome Standard Time

Because “Interstate 70 Blues” just doesn’t roll off the tongue. And that melodic hook should go down in history as one of the best country licks to ever lick! Cordle wrote one built for the long haul with “Highway 40 Blues.” It’ll keep you good company as you go wherever and back.

“Banjo Pickin’ Girl” – Annie Staninec

Is there any better reason to go around this world than being a banjo picker? There are never enough banjo pickin’ girls and this anthem, no matter how many times it’s picked up, studied, and retooled by another banjo pickin’ girl, always SLAPS. (Clawhammer pun intended.) Fiddler and multi-instrumentalist Annie Staninec, who’s traveled around the world making music quite a bit herself, gives an excellent old-time rendition of this favorite.

“A Crooked Road” – Darrell Scott

Darrell Scott turns a literary device pretty common in songwriting on its ear, with a tender eye for detail and emotion that he brings into all of his musicmaking. Life is, after all, about the journey — not the destination. Why not take the crooked, and thereby, the road less traveled?

Plus, take this song as suggestion: The Crooked Road, Virginia’s Heritage Music Trail, is well worth a visit. Put this song on and take the Crooked Road.

“Up and Down the Mountain” – David Parmley & Continental Divide

Work life doesn’t suit you? Does “paradise” mean a fiddle and the open road? If so, “Up and Down the Mountain” is for you and your road trip playlist. Especially if you’re planning on trekking through the Rockies, Sierras, Ozarks, Applachians, or what-have-you. Turn off cruise control, watch for the runaway truck ramps, and go up and down those mountains! David Parmley & Continental Divide know something about geography and topography, after all…

“Roving Gambler” – The Country Gentlemen

Not sure why you’d be headed to Las Vegas during one of the hottest summers on record, but if you’ve got your sights set on a casino — wherever it may be — crank up “Roving Gambler” and hope your 2 a.m. slot machine binge or your evening “re-learning” blackjack ends more amiably than with gunfire. Speaking of which, perhaps “Blackjack” deserves a slot on this playlist…

“Travelin’ Prayer” – Dolly Parton

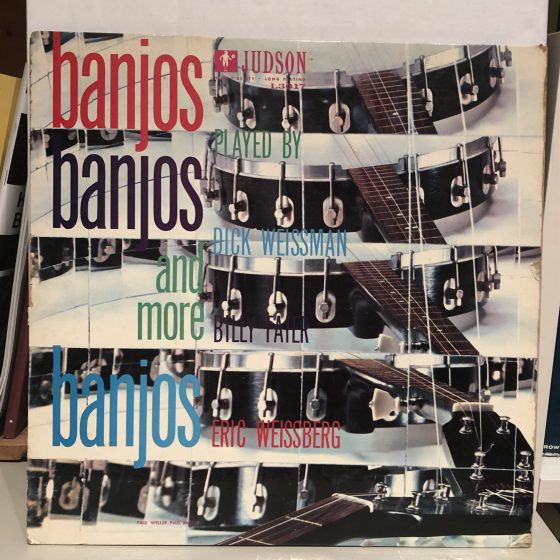

The kick-off of one of Dolly Parton’s masterpieces, her 1999 bluegrass album The Grass Is Blue, “Travelin’ Prayer” was actually written by Billy Joel. Yes, that Billy Joel. The original, from 1973’s Piano Man, featured banjo playing by Eric Weissberg and Fred Heilbrun. So of course the tune stands up to the bluegrass treatment and then some, between Stuart Duncan’s haunting fiddle cadenza to begin the track, the rip roarin’ tempo and train whistle harmonies, and the lonesome feeling of being away from your baby while he travels the world. We’re gonna assume Dolly’s blessed pen and ink added the lyric: “And keep him away from planes / cause my baby hates to fly!”

“Road to Columbus” – Kenny Baker

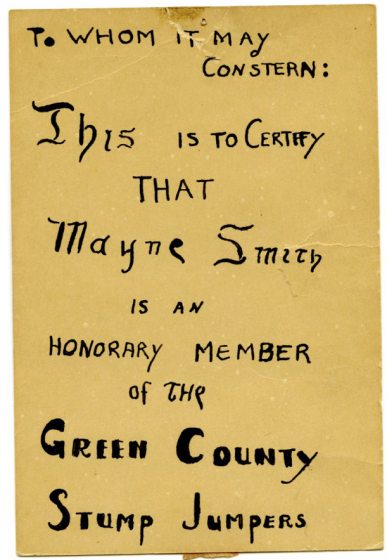

Growing up this writer frequented a bluegrass jam in Granville, Ohio, about 25 miles east of the state’s capital, Columbus. Like clockwork, every week as the jam wound down around noon on Wednesdays, Troy Herdman — a local bluegrass community stalwart, Doc Watson-style flatpicker, and mentor of many who lived in or around Columbus — would call this tune. Everyone would chuckle, and we’d play “Road to Columbus” as everyone, but especially Troy, hit the road to Columbus.

Herdman passed away last week at the age of 91. I certainly wouldn’t be the musician I was today if it wasn’t for Troy, and I know quite a few others who would say the same. So no matter where I travel, I always keep “Road to Columbus” nearby. Especially when I’m headed home to Ohio.

Many pickers speculate over whether Kenny Baker and Bill Monroe were referencing Columbus, Ohio, or Columbus, Indiana. But, according to Roland White — who introduces the song with an anecdote from his time on the road with Monroe — it’s about Ohio. For this Ohioan, that’s confirmation enough!

“That’s How I Got to Memphis” – Tom T. Hall

His own recording of one of his most popular hits may sound more like straight up and down country than ‘grass, but even the most casual fan of Tom T. Hall knows that this Bluegrass Hall of Famer is bluegrass to his core. If you’re headed down I-40 from Nashville — or, really, towards Memphis from any direction, no matter how direct or circuitous, this song is a must-add for your road trip playlist.

“Where Rainbows Never Die” – The SteelDrivers

This song is about a decidedly different kind of journey, not often referred to as a “vacation,” but even so it’s a poignant, encouraging, and downright delicious song to background any journey. If you’re road weary — or life weary — “Where Rainbows Never Die” is a certified pick-me-up that doesn’t shy away from reality, like the grit and coarseness in Chris Stapleton’s lead vocal wrapping you in its warmth. There’s a comfort in life not being sugar-coated — and in knowing somewhere, west of where the sun sets, rainbows never die.

“Home Sweet Home” – Flatt & Scruggs

Home never feels so sweet as when you’ve just returned after a long, restful, relaxing vacation. So we’ll close our summer vacation playlist with Flatt & Scruggs’ rendition of this tune pulled directly from the American songbook, “Home Sweet Home.” We hope a banjo roll always greets you at your door, and if not, this playlist will at least cover that for you. Wherever you roam, there’s no place like home! And no music like bluegrass.

Editor’s Note: Check out our follow up playlist, Take the Journey: 17 Songs for a Sunny and Warm Summer Vacation