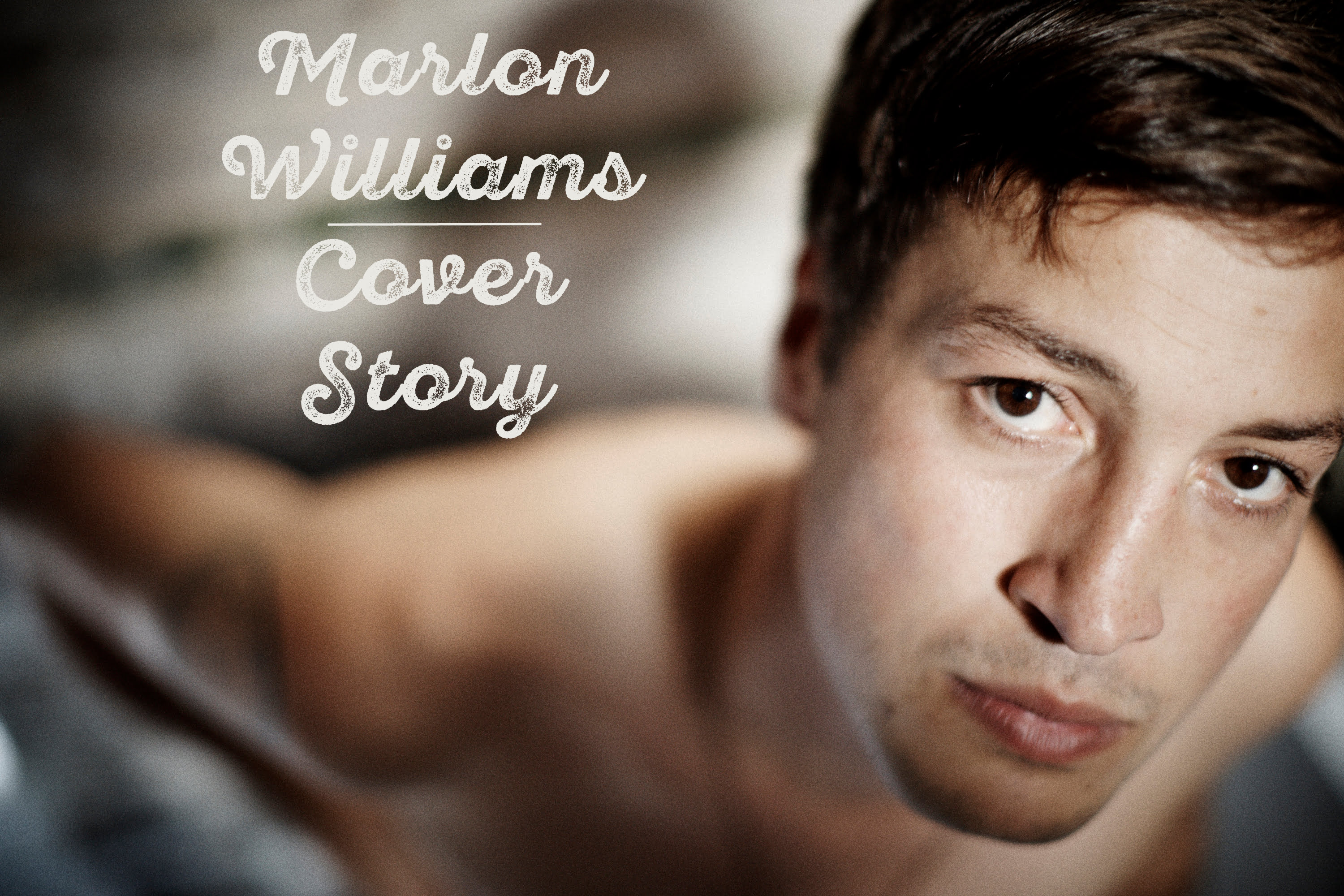

When he was in his early twenties, Marlon Williams watched a series of major earthquakes flatten Ōtautahi/Christchurch, the largest city in Te Waipounamu (the South Island of New Zealand). In the wake of that tragedy, the Māori New Zealand artist ascended onto the national and later international stage as a singer-songwriter, guitarist, and actor with a million-dollar smile and a golden, heaven-sent voice.

As a narrative device, it would be easy to enshrine his experiences during the earthquakes as a baptism by fire, a star emerging from the flames. However, as he puts it, “It’s tempting to say that experience fostered the folk scene here, but we’d been building something for a while before the earthquakes. When you look backwards through the haze of time, it’s easy to start telling yourself stories.” It’s a fitting reminder that things are never as simple as they look on the surface.

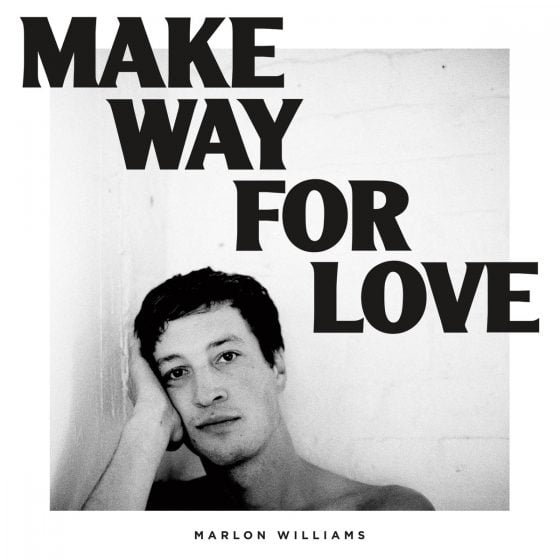

Now, fifteen years on, Williams is on the brink of showing us how deep things go with the release of his fourth solo album, Te Whare Tīwekaweka (The Messy House). In a similar tradition to the outdoorsy, range-roving sensibilities of his previous three records, the album represents an antipodean blend of country and western, folk, rock and roll, and mid-to-late 20th-century pop, connecting the musical dots between America, Australia, and Aotearoa (New Zealand).

This time around, however, Williams – a member of the Kāi Tahu and Ngāi Tai iwi (Māori tribes) – made the decision to step away from English and sing in his indigenous tongue, te reo Māori. Therein, his guiding light was a traditional Māori whakatauki (proverb), “Ko te reo Māori, he matapihi ki te ao Māori,” which translates into “The Māori language is a window to the Māori world.” As displayed by the album’s lilting lead singles, “Aua Atu Rā,” “Rere Mai Ngā Rau,” and “Kāhore He Manu E” (which features the New Zealand art-pop star Lorde), he’s onto something special.

During the reflective, soul-searching process of recording Te Whare Tīwekaweka, Williams found solidarity in his co-writer KOMMI (Kāi Tahu, Te-Āti-Awa), his longtime touring band The Yarra Benders, the He Waka Kōtuia singers, his co-producer Mark “Merk” Perkins, Lorde, and the community of Ōhinehou/Lyttelton, a small port town just northwest of Ōtautahi, where he recuperates between touring and recording projects.

From his early days performing flawless Hank Williams covers to crafting his own signature hits, such as “Dark Child,” “What’s Chasing You,” and “My Boy,” Williams’ talents have seen him tour with Bruce Springsteen and the Eagles, entertain audiences at Newport Folk Festival and Austin City Limits, and appear on Later with Jools Holland, Conan, NPR’s Tiny Desk, and more. Along the way, he’s landed acting roles in a range of Australian, New Zealand, and American film and television productions, including The Beautiful Lie, The Rehearsal, A Star Is Born, True History of The Gang, and Sweet Tooth.

From the bottom of the globe to the silver screen, it’s been a remarkable journey. The thing about journeys, though, is they often lead to coming home, and Te Whare Tīwekaweka is a homecoming like never before.

In early March, BGS spoke with Williams while he was on a promo run in Melbourne, Australia.

Congratulations on Te Whare Tīwekaweka. When I played it earlier, I thought about how comfortable and confident you sound. Tell me about the first time you listened to the album after finishing it.

Marlon Williams: It was that feeling of nervously stepping back from the details and seeing what the building looks like from the street. I felt really pleased with how structurally sound it was.

What do you think are the factors that allow you to inhabit the music to that level?

I’ve spent my entire life singing Māori music. No matter my shortcomings in speaking the language fluently and having full comprehension in that world, the pure physiology of singing in te reo Māori has been my way in. There’s a joy and a naturalness that has always been there. That gave me the confidence to take the plunge and really enjoy singing those vowel sounds and tuning on those consonants.

We’ve talked about this before. Part of what facilitated this was singing waiata (songs) written in te reo Māori by the late great Dr. Hirini Melbourne when you were in primary school (elementary school).

Those songs are so simple and inviting, especially for children. They really help you get into the language on the ground level. A lot of what he did for this country can feel quite invisible, but most of us have some knowledge of the sound and feeling of the language as a result. It feels like a really lived part of my upbringing. His songs gave me a push forward into something that could have otherwise felt daunting and deep.

For those unfamiliar, could you talk about who Dr Hirini Melbourne was?

Hirini Melbourne was a Tūhoe and Ngāti Kahungunu educator and songwriter from up in Te Urewera [the hill country in the upper North Island of New Zealand]. He was born with a real sense of curiosity about the world and a sense of braveness and self-belief about taking on Te ao Māori [the Māori world] and bringing it to people in a really straightforward way. Hirini decided the best way was writing songs children could sing in te reo Māori about the natural world around us.

If you listen to his album, Forest and Ocean: Bird Songs by Hirini Melbourne, you’ll also see a lot of Scottish influence in terms of balladeering, melodies, and instrumentation. Later, he started collaborating with Dr. Richard Nunns. They’d play Taonga pūoro [traditional Māori musical instruments] and go into some very deep and ancient Māori music. Hirini’s whole career was this beautiful journey that was tragically cut short [in his fifties].

When I think about your music, I think about historical New Zealand country musicians like Tex Morton and John Grenell, who emerged from Te Waipounamu before finding success in Australia and America in the mid-to-late 20th century.

I wasn’t super aware of that tradition until I learned about Hank Williams and completely fell in love with country music. After that, I realised there was a strong tradition back home. I guess it gives you a sort of reinforcement, a sense of history, and a throughline you can follow to the present moment.

I also think about New Zealand’s lineage of popular singers. People like Mr Lee Grant, Sir Howard Morrison, John Rowles, and Dean Waretini, who I see as antipodean equivalents to figures like Roy Orbison, Scott Walker, and Matt Monro. What does it say to you if I evoke these names around your album?

A lot of the celebration around this record is the celebrating the ability of Indigenous people – in this case, Māori specifically – to absorb what is going on in the world and make something from it. You can think about it in other terms, but I think about it in the sense of creativity. If you think about Māori religions like Ringatū [a combination of Christian beliefs and traditional Māori customs], there’s this willingness and this sort of epistemological elasticity to be able to go, “Oh, these things make sense together.” I can wield this tool. I’m going to come to it with my own stuff and create something unique and strong that is a blend of worlds. The main energy that was guiding me on this record was that tradition of synchronisation.

When do you consider to have been the starting point for Te Whare Tīwekaweka?

The literal start point was May 2019. That was the first time I sat down, had the melody and the structure of “Aua Atu Rā” and realised there was an implication in the music of what the song was about. This lilting lullaby was emerging. I’d say it was boat stuff. That was the first moment when I realised I was writing a waiata. I didn’t quite have it yet, but the phrasing was in [te reo] Māori, and I knew where it was telling me to go. At the time, I had a [Māori] proverb in my head, “He waka eke noa,” which means, “We’re all in this boat together.” I’ve always struggled with it. I believe it’s true, but we’re also completely alone in the universe.

From there, everything locked into place.

It strikes me that feeling connected could be considered an act of faith. You have to believe that it’s more than just you.

If I think about faith, I think about surrender, being humble, having humility, and going to a place I can acknowledge as new ground. I think faith is a useful word here.

Tell me about the conditions under which Te Whare Tīwekaweka came together.

It was pretty patchy in terms of the momentum of it. Once I had “Aua Atu Rā” loosely constructed, I took it to Kommi [Tamati-Elliffe], who helped me make sense of the grammar. After that, it sat there for a bit.

Kommi is a writer, rapper, poet, activist and lecturer in Māori and Indigenous Studies and te reo Māori. They perform te reo Kāi Tahu, the dialect of the largest iwi (tribe) within Te Waipounamu (the South Island of New Zealand). How would you describe them?

Kommi is a shapeshifter. I can’t work out how old they are. I found it hard to work out what they thought of me, but I knew there was this lovely softness there that belies a lot of deep thinking and some real sharpness. They’re very enigmatic as a person and a creative entity. One time, we got drunk at a party and talked about some work they were doing on phenomenology through a Te ao Māori lens. We were talking about that and making the most crass puns imaginable. There was this dichotomy of high-level and low-brow thinking that felt really playful.

What you’re telling me is you felt safe with them?

I guess. That’s all I can hope for in a collaborator.

Let’s get back to Te Whare Tīwekaweka.

After I’d been sitting on “Aua Atu Rā” for a while, my My Boy album came out. In retrospect, you can also hear a lot of the direction that eventually went into Te Whare Tīwekaweka was already starting in My Boy. That took off for a bit, but all the while, I was back-and-forthing on songs in [te reo] Māori with Kommi. They’d send me lyrics all the time and I’d play around with them without really committing anything to paper.

Once I was near the end of touring My Boy, I started to turn my attention back to Te Whare Tīwekaweka. Then I agreed to let the director Ursula Grace Williams make a documentary about me [Marlon Williams: Ngā Ao E Rua – Two Worlds]. I thought, “Right, they’re filming me, so I better do what I’m saying.” Part of the intentionality was that the documentary would frame it into a real thing and make it happen. There was nowhere to hide.

Across the album, you sing about living between worlds, love, the land and sea, the weather, solitude, and travel, often through metaphors that invoke the natural world. Why do you think you gravitate towards these themes?

On a very basic level, I’m a very sunnily disposed person in terms of the way I comport myself. I feel desperately in love with people in the world and feel terrified of losing people, situations or understandings. These are the things I think about. The fact that I write songs like this is my outlet for ngā kare-ā-roto [what’s going on internally] and my darker side. I like to be warm and friendly in how I deal with people, but a little bit more severe when it comes to matters of the heart.

What do you think it has meant to make an album like this right now in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu (New Zealand)?

Personally, I have a sense of achievement from having built something in that world. It also does something for my sense of family, in terms of representing a side of them very publicly that hasn’t always been accessible to them. There’s a lot of Kāi Tahu dialect on the album, so in terms of iwi, it feels good to put something on the map that speaks directly to the region. At the same time, this all sits within a very heated and fractious national conversation. On one level for me, it’s by the by; on another level, it’s great to have Māori music accepted into the mainstream. Whatever the political conversation going on is, if you can compel people with music, you’re really winning the battle on some level.

Taking things further, what do you think it means to be presenting Te Whare Tīwekaweka to a global audience?

Most places I go overseas, there is a sense of goodwill and excitement about marginalised languages being platformed. There’s a broader appetite due to people having instant access to a range of music through the internet. The threads you can draw together now are so vast and ungeographically constrained that I think people’s Overton window of what they’ll sit with and take in, even without knowing they’re not fully comprehending it, has shifted. I think people are generally either really open to that or completely shut off, which is something I don’t personally understand.

We can’t get around talking about Lorde singing on “Kāhore He Manu E.” It felt like she really met you where you were standing.

This speaks to the album in general. It was about bringing things to where I was standing. I didn’t want to jump into anyone else’s world. I had it in the back of my mind that I wanted her to sing on it. In the past, she kindly offered, “If you ever want me to sing on something, I’ll do it.” I could hear her on it from the moment I started writing it. There have been a few songs like that which have been very easily labored. They don’t take much writing and are always my favorite songs. It was important to me to get her involved in a way that wouldn’t be a post-hoc addition. She had to be part of the stitching of the record itself.

How do you feel in this moment, as you prepare to see what happens next?

I’m just excited to get these songs out into the world and see what they morph into when I start getting on stages and seeing what they do in a room. That’s going to change the way they feel and the way they want to be played. The second creative part of it is getting to the end of the tour and realising that the songs have become completely different from on the record. That can be a fun thing. Sometimes, it leads to remorse that you didn’t record them in the way they’ve gone. Other times, you realise you’ve completely ruined the song and gone away from what was good about it. I’m excited for the deployment.

Well, there’s always the live album.

Exactly.

Photo Credit: Steven Marr