I’ve had the good fortune of knowing Kentuckian country queen-in-waiting Kelsey Waldon for almost the entire time I’ve lived in Nashville — more than eight years at the time of this writing. I’ve stood over her unfathomably enormous cast iron skillet, filled to the brim with bubbling, sizzling battered fish. I’ve sung harmony on one too many choruses of “Smoky Mountain Memories” after perhaps one too many slugs of Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey with her, too.

And yet, in listening to her brand new album, White Noise/White Lines, I still found myself picking up fresh tidbits of her extraordinary yet downright ordinary approach to musicmaking, songwriting, self-expression, and artistic exploration. Waldon, despite limitless comparisons to almost every female country forebear to ever growl through a lyric, remains a paragon unto herself, a true singularity in realms of American roots music.

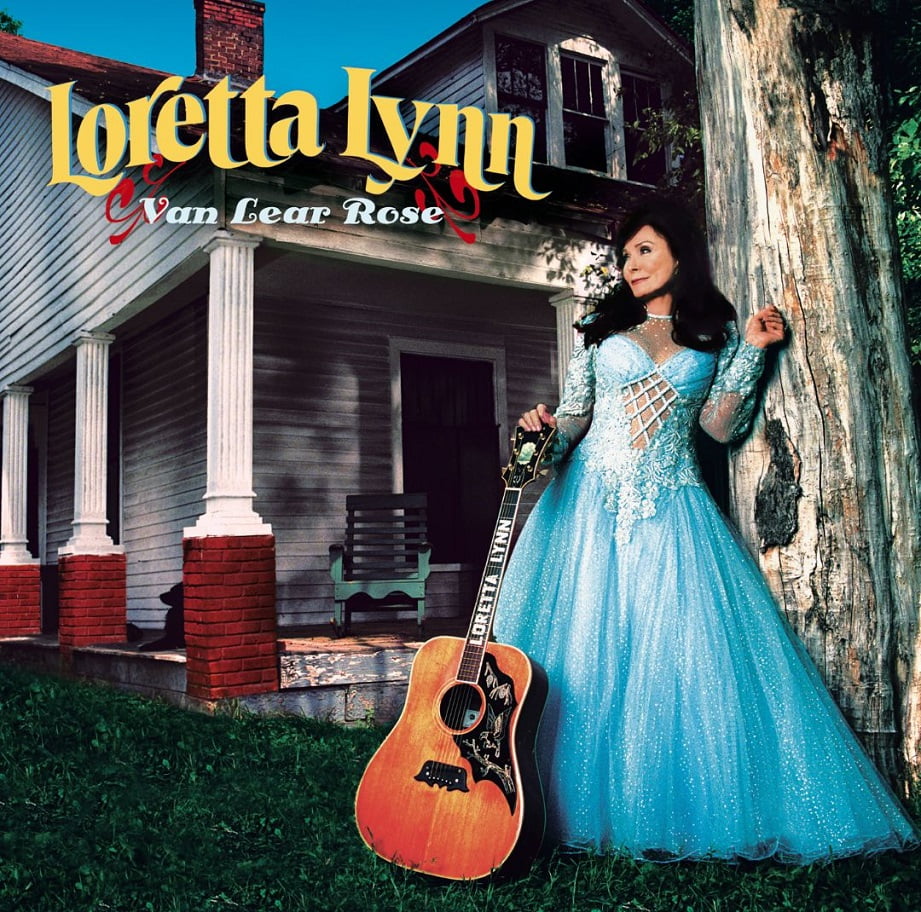

White Noise/White Lines cements the fact (which has always been plain as day to those who dug deep enough) that Waldon will refuse tidy, one-for-one comparisons to any/all other country stars and writers who have come before her or who count themselves among her contemporaries. Except perhaps two: Loretta Lynn — whose “Coal Miner’s Daughter” inspired Waldon’s own “Kentucky, 1988” — and John Prine. The latter is fitting, in so many ways, now that Waldon makes her label home with Oh Boy Records, label of the denizen of Kentucky songs, meat and threes, and plain spoken oracle-like wisdom through lyrics.

A brief album by many measures, White Noise/White Lines captures technicolor moments of Waldon’s life, her joys, her musings, and her homeplace, encouraging listeners to lean into the record’s brevity and engage wholly with each constituent moment therein. Because truth needs no more than a moment.

For BGS I made the trek out to Waldon’s cabin outside of Nashville and after a quick stroll around the vegetable gardens and a tour of the many Kentucky-themed decor items imported from one state north, we settled in the kitchen, sipping water out of mason jars, to talk.

People routinely refer to you as being similar to Loretta, similar to Tammy Wynette, Kitty Wells, Patsy Cline. People are constantly making these comparisons to these kind of foremothers of country and I wonder how that makes you feel, to be a bookend against someone like Loretta or Tammy Wynette?

Kelsey Waldon: Honestly, I think that’s an incredible compliment. Those are all, you know, my sisters that have gone before me, women that I’ve looked up to quite a bit. Especially in the country music realm. However, I also kind of feel like, especially with this new record, I think it’s apparent that hopefully I’m also finding quite a bit of my own thing.

Sometimes when people say things like that to me it’s like, well maybe their scope of country music isn’t that wide. When someone would be like, “You sound like Patsy Cline!” I’d be like, “Uh, no I don’t.” [Laughs] I mean, I love Patsy Cline and I hold her up as something sacred, I wouldn’t ever even sing Patsy just because nothing touches that.

I think it can kind of be, dare I say, a lazy comparison to just kind of name [some popular woman country star.] It’s definitely there. Even sonically, I was so inspired by them. Especially Loretta, absolutely.

I hope the new record showcases that with the years we’ve spent on the road — just using even my own touring band. It starts at country with me, I can’t just flip off a light switch and say, “Oh, it’s not country!” I guess some people can do that, but I don’t see it that way. Country is just so much embedded in me. No matter what form my artistic expression comes out, that’s still gonna be there. It just may not be cookie cutter, it may not be formulated. It may not even sound exactly like that. One thing that I think the growth of this record shows, hopefully, is that these are my songs, I’m not a throwback artist. I’m not a retro artist. I am an artist making music in 2019.

I did want to talk about your band, I think it’s remarkable. It’s getting more and more rare that folks tour with the folks who played on the record, because — and it’s not the fault of anybody — they’re trying to make money on the road. So if they stack their record, of course they aren’t bringing those people on tour. Why is it a priority for you to have the same band?

There are obviously all of these amazing musicians out there who are session musicians and a lot of people I’ve been fortunate enough to play with myself. I’ve learned a lot from [them]. This time around, this was always a goal of mine, to have a record that had a band I wanted on it. I worked really hard to find the band to really fit those pieces together. It took me a while… just trying to figure out really what I wanted. My last record, I’ve Got A Way, caused the right people to gravitate towards my music. I mean, I eventually found the band that I have now because they heard those earlier records and they were like, “I would love to be a part of this.”

The band I have now, which is Mike Khalil, Nate Felty, and Alec Newnam — and Brett Resnick played on the record, but he doesn’t get to play with us a lot anymore, he plays with Kacey Musgraves, which is wonderful. But with the band I have now I just knew it. I was like, “I think this is it.” We all knew it. Even Brett. People were like, “We think this is the right combination.”

In that way, too, there’s nothing wrong at all with using session players, I just think, honestly — and I might be a little biased — my band is just as good as any. I think they could, and they will be one day, they will be those session players. They care so much about their craft and they work hard. I’m very lucky.

One of the things that excites me most about this record is that I’ve always heard the bluegrass influences in your music, but they’re really forward in this record. Especially in your rhythm playing, in your rhetorical style in your writing, in your vocal phrasing, even in the arrangements with the twin fiddles and there are a couple of “fast waltzes” on the record. I love that “Lived and Let Go” really could be played on bluegrass radio.

I think that is such a huge compliment, thank you.

It’s bluegrass! I wanted to ask, and not just because we’re The Bluegrass Situation, but in general, because this is a huge part of the canon of music you reference and that you listen to. Who in the bluegrass sphere influences you now and who has in the past — and I’m gathering Ola Belle Reed is at least one of them.

I love Ola Belle, obviously, we did an Ola Belle song on the record. Well, I love that you can pick that out. To me, I feel like it’s plain as day that there’s a bluegrass influence all over it. To some people it’s not as apparent, I guess. I’ve had some people just be like, “What is this thing that you’re doing?” It’s because they don’t listen to bluegrass. I’m like, “I STOLE that!” [Laughs]

I guess I understand now why they don’t put those two together, if you’re talking about mainstream country, because that’s clearly not. But to me, I’m always like, “Of course bluegrass is country.” It’s also bluegrass, but it’s also country. It’s like the OG country music.

I would say one of my favorite influences, one of my favorite singers ever, is Dale Ann Bradley. She’s up there for me. I really think Dale Ann should be a legend, honestly. And Ralph Stanley, and obviously I love Bill [Monroe], and Jim & Jesse, and all those groups. And early Keith Whitley, I’ve been obsessed with that for a long time.

I think it’s interesting that you mention both Ralph and Keith back to back like that, because you can hear elements of both of their vocal phrasing and vocal techniques, in what you do singing-wise.

The same thing with Dale Ann. They have such unique registers of their voices and it’s something that I really relate to. Sometimes I didn’t really know what it was that I was doing. I could kind of hear my own voice in [their vocals]. If that makes sense? I could really relate to that. It’s so soulful.

I feel like Keith could sing on anything. [Laughs] He sounded exactly like Keith. That’s the beautiful thing about a country singer to me, he could sing on an R&B track and it would be sexy as hell. It’s like George Jones — and Dolly can sing on anything, as far as I’m concerned. That’s a great singer, to me. Ralph, I’ve always said that he is like the Pop Staples of mountain music. It’s like he doesn’t even have to be loud, but he is so loud. He’s barely singing. He’s just projecting. I love Flatt & Scruggs as well.

New artists… Molly Tuttle, I love what she’s doing. That new record. She’s really taking a genre and making it her own. Something that’s not worn out or tired. Doing something fresh. She has accomplished making this new for people. In my own way, I hope to do that as well.

I don’t guess there’s anybody else completely new, besides like Sister Sadie, and Dale Ann! [Laughs] They are some BAD girls!! Dale Ann, man. The mark of a true artist is that she can sing all of the covers she does. Like I said, I think Dale Ann should be a legend.

Words are clearly your priority in your songwriting. You’re prioritizing what you’re meaning to say first and foremost, then making the melody and music and everything work around what you’re trying to say. It sounds effortless when you listen to it, but I wonder what kind of intention goes into that?

Songwriting is kind of interesting to me in that way. I’ve actually heard a couple people be like, “It sounds effortless.” Sometimes, it is effortless and you’re just like, “Wow that kind of poured out of me. I didn’t realize it was in there but it poured out of me in like five to ten minutes.” With this record, though, there were definitely a couple of things I had to go back to. I had the meat and taters, but there were a couple of things I rewrote and made sure made exactly the sense I wanted them to make. There’s a balance there, too. You don’t want to kind of go too far, over-analyzing the whole thing.

With “Kentucky, 1988,” I think your songwriting up to this point has felt so personal, and so tightly intertwined with who you are, that I almost didn’t realize that you hadn’t written this exact kind of song, yet. What brought you to the point of wanting to be that direct with telling your origin story? Was it more intuitive or more purposeful?

That was definitely purposeful. That is awesome that you’ve observed that, because I’ve felt the exact same way. I was writing new songs and I felt like, “You know, I haven’t written my ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter.’” I don’t really have something that is kind of like this definitive origin story. I just set out to write it. The title was actually kind of inspired by someone I forgot to mention, Larry Sparks — one of my favorite singers.

Oh my gosh!! “Tennessee, 1949!!”

Yeah! Yeah, it was inspired by that. That and a Tom T. Hall song that has Kentucky and a year in the title, with the comma and everything. In my head all of that sounded so cool. Everything about it, the rhythmic feel, it all rolled right off my tongue great. I just had to write it. People always [say], “That’s very vulnerable and transparent.” Well yeah, isn’t that what we’re supposed to do? [Laughs]

I know a lot of artists say this, but I definitely think this is the most personal thing I’ve done so far. I think all of it has been very transparent, in a way. I want to completely embrace that. I want to be as much of a freak as I want to be. It’s not like I was afraid to before, I just don’t think that I was ready. My mom always said I was a late bloomer, but she said, “When you bloom, baby, you’ll bloom!”

I did want to ask you about the significance of the Chickasaw Nation members singing on the record. We hear them at the end of “White Noise, White Lines.” What’s the personal significance of that for you? And are you a tribal member? Is anybody in your family a tribal member?

No. All of the Rollins side of my family, which is my granny’s side, they were all of French and Native American descent, but I never claimed anything like that. I just think it’s been something that’s been such a part of where I grew up, culturally. Even just hunting for points [arrowheads] and having such a respect for that way of life and culture.

It’s always really hard to keep this story short, when people ask me about the song, because I wrote it right after this amazing experience I had back home in Monkey’s Eyebrow, Kentucky, my hometown. When I went back to watch a ceremonial dance that the Chickasaw from Ada, Oklahoma [performed]. They came to re-bless the Wickliffe Mounds. They ended up lodging at my Dad’s that night, for free, [he was] cooking the food, doing the catering and stuff. I ended up staying down there and visiting.

We just became friends with the members of the tribe. We had so much fun. They’ve kept in touch… My dad took them arrowhead hunting for the first time, and they were doing ceremonial dances out on my dad’s land as well. I think he really really was appreciative of that. We were kind of the only people who ever lived down there in those river bottoms, maybe besides [the Chickasaw]. I mean, it’s the river bottoms. That’s why we find all these artifacts. No one has been down there except us.

I just remember thinking about how awesome the weekend had been and the radio had been on white noise for literally fifteen minutes and I had no idea. I was just in this tranquil moment. The song is just a detail of all these things. The solar eclipse had also blown my mind that weekend. Just realizing how small we actually are, compared to what is even going on in this universe.

Naturally, I included the details. “Chickasaw man got a buffalo skin drum,” because Ace — Ace Greenwood and Jesse Lindsey, that’s who’s on the song — actually did have a buffalo skin drum. It was pretty badass. My dad asked them to sing some songs on the porch. I love Ace’s voice, it reminds me of Ralph Stanley. It’s a voice that just feels like it’s been there for a long time. It’s so pure. I just loved it, I was really touched.

He sang a song that had been in his family for generations. The message of the song was basically, “Though I’m far away I’m still near you. No matter where I am. We are together.” In that moment that really was something I needed to hear. I put that [on the record] not only because I thought it was beautiful, and I wanted people to experience what I felt, but I also wanted the record to feel like an experience.

Ace told me one time when we were down there that the media likes to tell his people who they are and that’s not who they are. I think in a way, perhaps it’s also why I thought it would be really beautiful to have that at the end as well. I hope it doesn’t seem like it was for my own reasons, I guess. I was just writing about that weekend and I felt like it was so beautiful to me I wanted it to be documented.

I think it makes a lot of sense. And I’m not saying it’s not a complicated thing to talk about, or that it doesn’t trip into some territory that we as settlers will never fully understand, but I do think that it follows perfectly with you bringing your whole entire self to your music. So much of what you do is tied to place and is tied to coming from Kentucky.

That was another part of it, showcasing where I’m from. And the cultural background of it.

And not just the colonial background of where you’re from?

No. I mean absolutely not. To me, that’s exactly how I saw it. Nail on the head. It might cause a little bit of question, but I think that’s good. ‘Cause then I’ll get asked about it. And then I’ll tell ‘em. [Laughs]

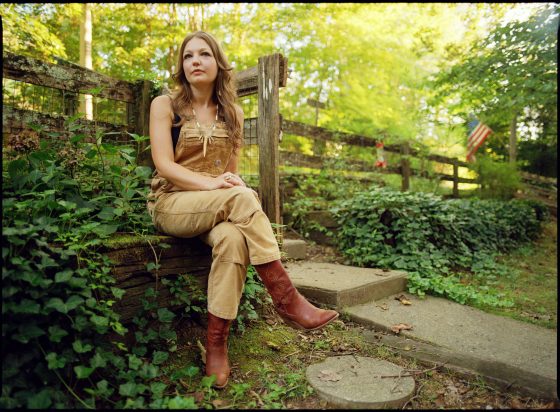

Photos by Laura Partain for BGS. See the entire photo story.