To make his eighth proper album as Hiss Golden Messenger, M.C. Taylor left his adopted hometown of Durham, North Carolina, and went… everywhere? He booked studio time in Nashville, tracked songs in New Orleans, and headed north to upstate New York, where he recorded at the studio owned by The National’s Aaron Dessner. There might have been even more cities in that list, but logistics and time cut his traveling sessions short.

“I wanted to make a record anywhere other than Durham,” he says. “I felt like I needed a change, and it felt like the songs were asking for a change. This is a wandering record. It just felt like the songs were wandering around a little bit. So I felt like maybe I should, too.”

Travel is a major theme of his music, both as inspiration and consequence. Working as a musician means touring; providing for his family means leaving them. Out on the road, however, he finds new reasons to make music. Taylor peppers Hiss Golden Messenger songs with place names, references to home and elsewhere. For Terms of Surrender he decided he needed to make that part of the creative process, which meant recording wherever he landed.

Taylor’s wanderlust extends to the music, too, which draws from a range of roots traditions: psychedelic folk and rural funk, southern soul and classic rock, American primitive guitar and ‘60s frat rock, J.J. Cale and the Staple Singers, Neil Young and composer Harry Partch. The result is a sober but hardly somber album that surveys America at the end of the 2010s, during a moment that is — to say the very least — tumultuous.

BGS: Place always feels so important to your music, so it made me wonder if getting away from a place was as important as getting to a place. Could you have made this record back home in Durham?

Taylor: Yeah, I could have made it in Durham. Definitely. But it would have a very different character. I try not to think of the records as the final form of the songs. I think of them as snapshots of the songs, snapshots in time — a documentation of the tunes as they exist among a certain group of people on a certain day in a certain city. So this particular version of Terms of Surrender is a document of that particular time in my life.

Given that these are wandering songs, and given that you’ve talked about the album coming out of a very hard year, how did that inform the music?

The trials and tribulations I was experiencing are obviously threaded through the songs. Some of that is maybe obvious lyrically, and some of it is a little more coded. It’s something that is obvious only to me. I was dealing with those issues in the composition of the songs, but the making of the record was pretty joyous. Actually, the writing was, too, because it’s always a cathartic experience.

So I can’t really say that I went into the writing of the songs in a tortured place and came out with all the answers. The songs were just a way for me to speak about that stuff, to process it in a way that made me feel like I was evolving emotionally. Not that I was solving my problems, but I was at least beginning to understand what they were. We don’t find an answer in an instant, but we can identify the issue and over time find ways to address it.

To what degree can you talk about the events that informed this album?

It’s a tricky question, because it was something that was part of the fabric of my life for the last year or two. It’s something that comes up in the one-sheet because every record has to have a story, but then when it comes time to talk about it, it’s tough. You never know how much you want to reveal, you know what I mean? I’m a pretty open person but there’s this curtain between all of the stuff that I make public and all the stuff that I keep private.

So I’ll just say that I had some personal problems with someone that I worked very closely with. It felt like over the years they had become an emotionally abusive person. I couldn’t even put a name to the things I was feeling because of that relationship. I thought I had lost my way a little bit. Over time I came to understand what was going on and was able to extricate myself from that relationship. That was important. And then to have all that against the backdrop of the way our country feels right now… it was a lot. I’m a sensitive guy, I guess.

That definitely seems like something that informs these songs, but it’s not a political record. It’s more about living at a certain time when these things are encroaching on your mental health.

And I want to be clear: I’m one of the fortunate ones. I’m a white man in this country. I’m living on Easy Street compared to people of color, queer people, women. But that was a question that came up on the last record, Hallelujah Anyhow. That wasn’t really a political record either, unless you realize that everything is political. The personal is political; the emotional is political. But that record and the new one were made a different times, so the relationship to hope is different.

That’s something I picked up on: this sense of optimism as well as something like joy. That’s not necessarily a word that I associate with this time in history, but it comes through on a lot of these songs.

On Hallelujah Anyhow joy and hope seemed like these bright, sharp things, a nice glinting in the sunlight. They could cut through just about anything. But they work differently on this record, I think, because you realize that we have to work at them every day. If we don’t, they’ll become dull and unwieldy.

And hope and joy are things that I have to work at. Some of these songs are reminders to myself to work at these things that bring me hope and joy. You have to keep that bright thing sharp. It’s like marriage: If you stay in a marriage long enough, you realize that it takes a lot of hard work to keep it going. I’m pretty sure that that’s the way forward for me if I want to survive.

Is it difficult to get into that mindset when you’re writing, to remind yourself of these larger goals?

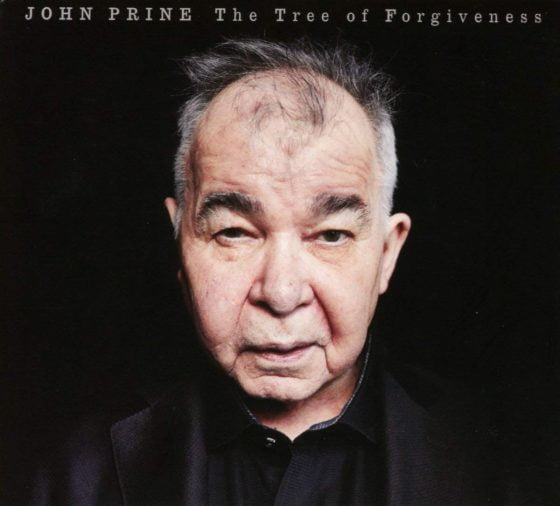

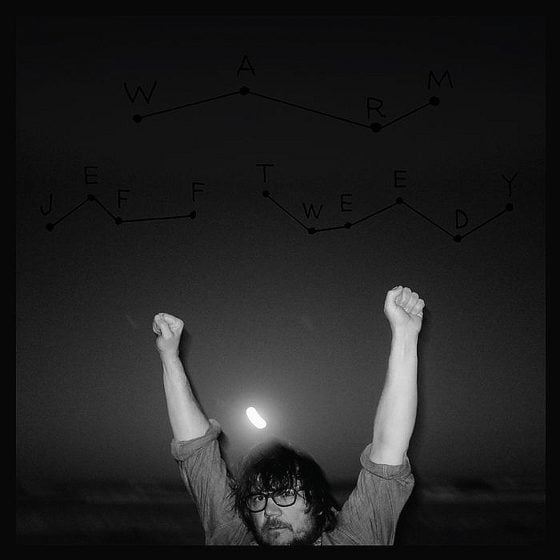

There are days when I wake up and think, I don’t want to make this music anymore. I don’t want to make any music anymore. This isn’t something that’s making me happy anymore. There’s too much competition, too much saber-rattling, which is all so superfluous to what we all actually do. I guess I’m interested in people who have been making music for a long time, because I want to be in this for the long haul. How does their language change over time? How do they adapt to survive in the world?

You mentioned that you wrote these songs as reminders to yourself. Does that change how you relate to them on the road, when you have to perform them night after night?

That’s why I try to approach records as snapshots. I know the songs are going to change every night, because of the emotional content in them. That changes the phrasing of how I sing certain things. Part of that comes from my emotional understanding of the songs, you know? The other part of that is that my favorite songs are the one I write without totally understanding. Usually I’m not very satisfied with them when I get them down on paper, but eventually I realize that if I live with that dissatisfaction, it’ll becomes something different.

It’s like there’s a hand that is guiding this stuff. It’s not God-like; it’s more an unconscious feeling that it’s okay to feel that way. It’s OK to feel like, “OK, this is as good as I can do right now. I don’t have the time or the emotional capacity right now to make this any better.” And then you just leave it. It’s like planting a seed. It grows even though the words on the page don’t change.

Is there a particular song in your catalog that changed or grown like that?

I would say most of the songs that are in live rotation remain in the set list because there is that element of discovery from day to day or week to week. “Blue Country Mystic” [from 2012’s Poor Moon] is a good one. And there’s one on the new record called “Down at the Uptown,” which is about this dive bar where we all used to hang out in the Mission District in San Francisco. This was many years ago, late ‘90s. It was a formative place for many of us.

I knew that I wanted to write about that time in my life, and I did the best I could. But it felt clunky. I thought, I’m just going to leave these words here and hope that if something better does come along, it’ll be better than what’s on the page now. But the process of singing it in rehearsals has made me realize that no, this is really good. Not a great song, but for me it’s good. It does the thing that I needed it to do.

That one did stand out because it seemed like a very specific reference to a very specific place. I thought it might be in North Carolina, but I was on the wrong side of the country.

I don’t even know if the Uptown is still there. When my friends and I moved to San Francisco in the late ‘90s, we found this bar on the corner of 17th and Capp in the Mission District. It was pretty scuzzy, you know. But the Uptown was this little hidden waystation where all of us learned to drink. There were a lot of promises made at that place, some of which we kept and some of which we didn’t. It was a clubhouse. And the jukebox was very educational. Lots of stuff on there was way above my pay grade. That’s where I heard Patti Smith’s “Horses” for the first time. I’d be lying if I said I loved it immediately. But all of my favorite music is not something that’s immediate.

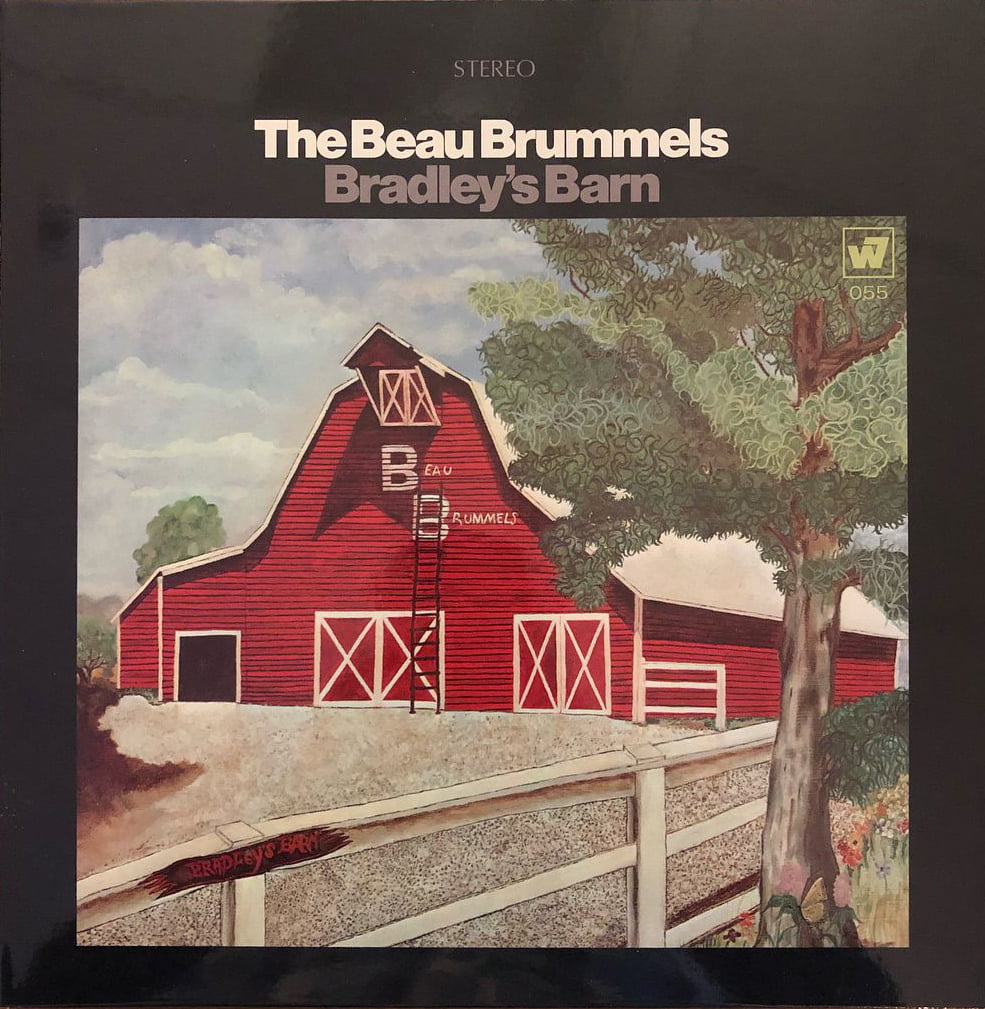

I was an adult, but I was still a child in a lot of ways. I was out of the punk rock phase of my life — at least musically, not spiritually. I wanted more, but I didn’t know how to do it. It was a time when I was discovering all of the music that has continued to inform my life. So Patti Smith, but also the Silver Jews, Johnny Paycheck, Merle Haggard. All of that stuff was coming into my life at that time, and it was overwhelming in the most beautiful way.

That discovery of oneself is thrilling. It’s exhilarating to find a formative record one day and the very next day it’s another record that brings a similar emotional resonance. It happens less now because I’ve heard more. But every time I have that feeling, it’s wonderful.

That gets at something I’ve been thinking about regarding Hiss Golden Messenger. You’ve got eight albums in ten years, which is very prolific. How do you manage to keep things fresh for yourself?

Just trying to remember why I started doing this in the first place is usually the best way. I try to make sure what I’m doing feels vulnerable and genuine. Whether or not it feels fresh to other people? I don’t know if that’s something that I necessarily feel I should concern myself with. I hope people continue to find things in my music that moves them, because I’m still discovering new things in the music.

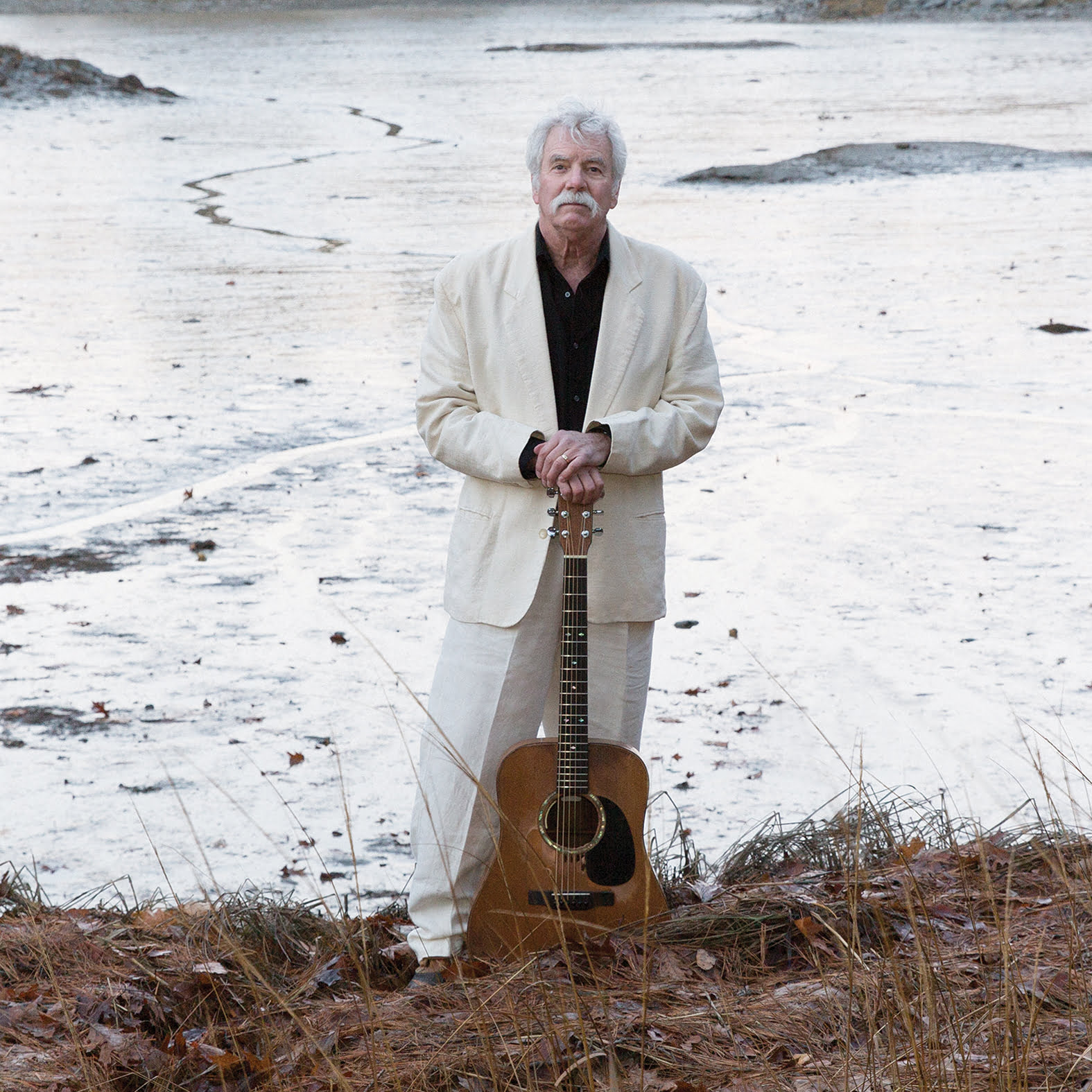

Photo credit: Graham Tolbert