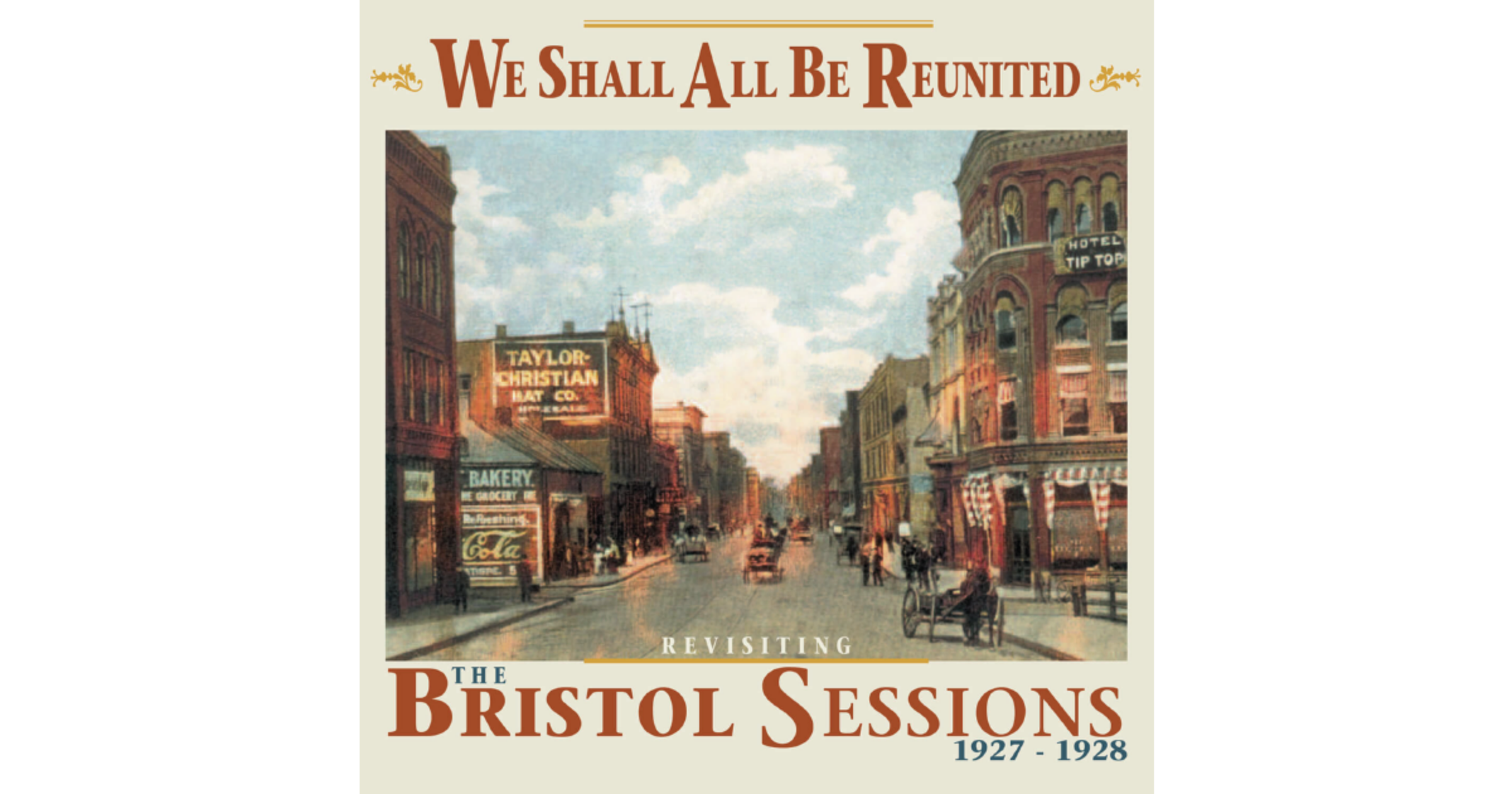

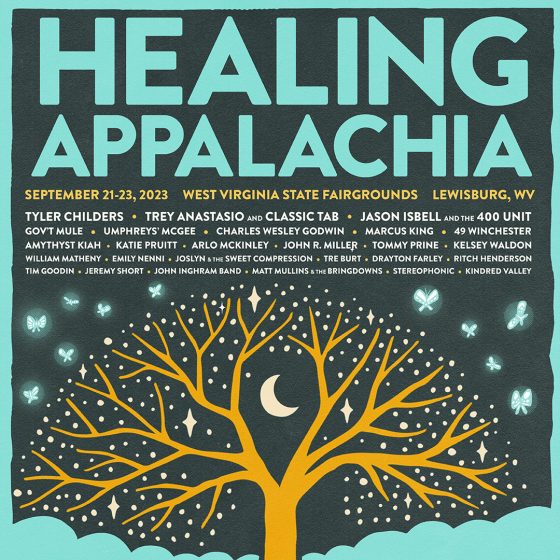

This weekend, September 21, 22, and 23, at the West Virginia State Fairgrounds in Lewisburg, West Virginia, ascendant, down home country star Tyler Childers and his cohort will gather for an event begun in 2018 called Healing Appalachia. The benefit festival, put on by West Virginia based non-profit Hope in the Hills, will include performances by some of the biggest and buzziest names in American roots music: Jason Isbell & the 400 Unit, Trey Anastasio Band, Marcus King, Umphrey’s McGee, Amythyst Kiah and many more.

Healing Appalachia is just one of many such community-led, collective efforts born from within the region in recent years that is working towards effecting positive change while offering local, ground-up solutions to big, systemic problems. Their social media and website put it elegantly and succinctly: Their vision is a prosperous Appalachia, free from addiction. The opioid crisis has hit Appalachia, especially West Virginia and Childers’ home state of Kentucky, incredibly hard. When 26 people overdosed on one day in Huntington, West Virginia, in 2016, the mission for Hope in the Hills and Healing Appalachia was born.

At the time, Childers and his hardscrabble team were still climbing the music industry ladder, building connections and community that would eventually grow and blossom into the multi-day event Healing Appalachia has become today. Childers’ friend and manager, Ian Thornton – who founded WhizzbangBAM, the booking and management company that represents Childers – together with festival program director Charlie Hatcher, Hope in the Hills board president Dave Lavender, and others took that tragic day in Huntington and turned it into an accretion point, around which they gathered and took action. Now, the festival has a local, annual economic impact approaching $3 million while raising thousands of dollars to be distributed to local, on-the-ground organizations and non-profits that specialize in addiction programs, recovery, support, and healing for this long-oppressed region of the world.

We spoke to Ian Thornton and Dave Lavender for a two-part interview preview of Healing Appalachia, that dives into the work of Hope in the Hills and explores this grassroots music event’s community-first mission, that hopes to heal these music-steeped, underestimated communities in Appalachia from the inside out. Read our conversation with Dave Lavender below, read our conversation with Ian Thornton here.

Unable to attend the festival this weekend? You can donate to support the cause here.

Can you talk a bit about the impetus or inspirations for Healing Appalachia?

Dave Lavender: Hope in the Hills, our non-profit, was started in 2017, and then the first Healing Appalachia was held in 2018 as it took a minute for Ian Thornton, Keebie Gilkerson and Charlie Hatcher, and the other OG board members to get the all-volunteer non-profit going.

The birth of the group is rooted in the events of 2016 – two historic things happened that year. In June 2016, central West Virginia got record flooding that killed 23 people. Shortly thereafter, the Huntington music scene, which was really getting built-up in a mighty way with touring bands, came together and raised more money in one night at the V Club than some big corporate fundraisers had in a couple weeks. I think all of us there saw a ragtag bunch of musicians could really make a difference banding together. Interestingly, Tyler Childers and the Food Stamps’ first New York City trip was that August as well, for a West Virginia flood fundraiser organized by our friend, Michael Cerveris, the two-time Tony winner from Huntington.

As that was happening in August 2016, Huntington, West Virginia, hit the world’s headline news with 26 overdose calls within four hours. It might have been a shock to the world, but we were all living around it in West Virginia so Ian, Tyler and Charlie Hatcher, Healing’s co-founder and show producer, knew how bad it was, and knew it was time to project the “bat signal” in the air, and unite their super friends in music to gather again and put on a show to help out the boots-on-the-ground folks overwhelmed and trying to assist in this opioid crisis.

One thing that struck me about the organization and the event is how y’all are from the region and building support systems, resources and pathways for folks from within the region – can you talk about the importance of mutual aid and community to the org and also the event?

DL: Everyone in the world knows the West Virginia theme song is “Country Roads,” but I would say the West Virginia and Appalachian motto is a song from Slab Fork, West Virginia-native Bill Withers. He wrote “Lean on Me” about being raised in the coal camp where you rely on your neighbors. Being from Appalachia, we know help is not on the way and that we are also better and stronger together.

For Hope in the Hills as a granting organization, we try to stay acutely aware of the ever-changing recovery ecosystem and fill the gaps where we can. For instance, I think the general public thinks of the opioid crisis as, “That’s the guy with the backpack at the recovery house.” Yes, true. But, the opioid crisis has created deep and wide fall-out – from historic numbers of kids in foster care (addressed by Barbara Kingsolver in her latest Pulitzer-Prize winning book, Demon Copperhead), to an overloaded prison system with non-violent drug offenders to many governments not wanting to fund harm reduction – even though they know through countless studies that it saves lives. Without harm reduction, communities are likely to get horrific spikes in hepatitis and HIV.

We try to put what funds we have into the gaps to provide a little help, but to also let folks know through our socials about some of these amazing programs happening across the region with things like camps for kids in trauma, and innovative recovery-work programs.

As for the event, I think that “Lean on Me” spirit is really palpable everywhere you look at Healing Appalachia. We’ve modeled ourselves in the spirit of using music to create social change, after Farm Aid. Healing is shining a light on a crisis that many choose to ignore. We’re highlighting amazing people who help daily to deal with that crisis. We’re inspiring attendees through the music, testimonials from the stage, and the dozens of service providers there, to go forth and be the change when they get home from the concert, wherever home is. And that home is widespread – last year we had folks from 38 states and 3 countries.

The message I hope the casual music fan receives in their heart and acts upon from Healing Appalachia is that the opioid crisis is not “us and them,” it’s just us. Last year, we lost more than 109,000 in the United States to overdose. Music is a powerful vehicle for conveying with love that message of empathy. Even if you haven’t lost someone personally to overdose, we lost Prince, Tom Petty, Whitney Houston, and a long list of beloved musicians to opioid overdoses. So I hope that at the very least the casual music fan who comes just to see some amazing bands, goes back home with an improved empathy muscle that allows them to lay down the proverbial stones and jokes and judgment they were set to throw at someone suffering from Substance Use Disorder and in active addiction.

For the recovery service groups coming to Healing – and this year we will have more than 40 from 13 states – I want them to know, that as Mavis Staples sings, “You’re Not Alone.”

That they hopefully will meet folks from organizations like them who are in the trenches everyday, doing the hard, tedious and often-unsung work of helping someone along their journey, and that they may pick up some best practices, some group to ally with, and some friends from across Appalachia who know their struggles and can be an encourager.

Do you have a favorite anecdote or story about a partner organization or individual or program that was particularly impactful, or a perfect representation of why you do what you do?

DL: At Healing Appalachia last year, Kenney Matthews, the ONEBox coordinator for Drug Intervention Institute was one of our main speakers. I’m typically running around taking care of a lot of back-end stuff at the fest, but I was out there with him before he went out. He was really nervous, but I hugged him and told him he was going to crush it. He did, and threw down this beautiful line about “the opposite of addiction is connection.” It really was electric, so real and so true. I was talking with my wife, Toril, after Healing and Kenney – who spent 15 years in prison – told her about running into a prison guard who knew him on the inside at the festival. The guard tells Kenney he never did think he would change and that he was really proud of him, and they both had a moment of healing at Healing. We’ve had LOTS of moments in doing this work and the fest is full of them, but I loved hearing both sides of Kenney’s story and its impact to spread hope.

How do you – either individually or as a group – see music and the arts (especially arts with regional ties, like folk and country music and folk arts) as part of these regional solutions to regional problems?

DL: In Appalachia, storytelling and music are so grapevine-wrapped in who we are, how we think, what we do, so connecting and teaming up with those artists who are using their music with intent and purpose is what we want to do.

As a group, Hope in the Hills, we’ve been building out a Music Is Healing program that has active music therapy programs in East Tennessee with Cecilia Wright (who plays cello with Senora May and who has her own band), and in Eastern Kentucky at ARC and West Virginia with Huntington-based music therapist Margaret Moore (a multi-instrumentalist folk artist who also teaches the Wernick Method bluegrass jams). She also happens to be an expert in forward facing trauma.

The inspiring thing is we are bringing folks like Cecilia and Margaret – with that intersectionality of professional musicianship and therapy – to team up with other regional artists of all genres and do sessions not only at drop-in centers and recovery houses but also at regular music festivals to spread the fact that music is therapy and can be tapped into to get on a higher spiritual plateau.

At Addiction Recovery Care (ARC) Centers in Eastern Kentucky, Margaret gets to work with world-class bluegrass artists Don and John Rigsby, long-time nationally-touring bluegrass artists who are sharing their music to inspire folks on their recovery journey. Through ARC, Don’s built out a studio in Lawrence County, Kentucky, where he is teaching some of the ARC guys the recording industry. Along those career pathway lines, at Recovery Points in West Virginia, Hope in the Hills (Dave Johnson and Charlie Hatcher) have been working with folks there who have in years past helped build Healing’s stages and do stage-hand and festival security work, get paid for additional festival work as a career pathway build-out as an employment option.

Hope in the Hills is also helping fund the WVU School of Medicine’s music therapy program at the opioid unit. We’re also contributing to the inspiring Troublesome Creek Stringed Instruments program with Doug Naselrod in Eastern Kentucky, where Doug is doing music therapy while also carving out recovery-to-work opportunities for his world-class luthier shop making traditional music instruments.

Specifically for Healing, we’ve leveraged the fact that we have a large audience to help train them on using Naloxone. Last year (the first year back after two years off because of COVID), we teamed up with the WV Drug Intervention Institute to have a Naloxone training tent that really broke down the stigmas of Naloxone with a festival spirit. Our buddy Joe Murphy got Gibson Gives involved and we loaded up swag bags with Tyler CDs, water bottles from Healing, and then additional swag from other artists.

Are there particular bands/artists/acts on the lineup this year you’re especially excited about?

DL: Gotta give crazy props to Charlie Hatcher and Ian Thornton for pulling aces and connections to reel in an insanely good lineup that includes 24 national acts. This is only our fourth Healing Appalachia, so to have Marcus King, Umphrey’s McGee, and Warren Haynes and Gov’t Mule back-to-back-to-back – would be the envy of jam band festival in the world! Truly a guitar lover’s feast on Friday. And opening act Joslyn and the Sweet Compression is one of my favorite R&B bands out there.

I’m really knocked out that 49 Winchester (who’s up for Americana Group of the Year) are throwing down for two nights in a row hosting our Late Night Jam with some killer bands and songwriters on those bills.

As far as really impactful musicians and people in that recovery space, we feel beyond blessed to have Jason Isbell & The 400 Unit on Thursday as the headliner and then Trey Anastasio and Classic TAB on Saturday headlining with festival co-founder Tyler Childers and The Food Stamps. Isbell, who was on a recovery panel at SXSW 2022 with our good friend Jan Rader, has put in the hard work to become increasingly more comfortable and sure-footed in that space and has Weather Vanes fresh out — the album to prove it. That’s been inspiring to watch.

We’re over the moon to have Trey (who is 15 years in recovery) with us and bringing Classic TAB, after a full summer of Phish shows, and with the great news that his 40-bed recovery center Divided Sky Foundation is on the way to opening in Ludlow, Vermont.

As a West Virginian, I’m super stoked to get Charles Wesley Godwin back on home turf to do something so real. I think he could grow into the biggest thing out of West Virginia since Brad Paisley. His new 19-song album, “Family Ties,” drops the day after he plays Healing on Thursday.

What does a healed Appalachia look like to you?

DL: The problems are many, but the power of collective hope is growing and change is in the air all over Appalachia.

A healed Appalachia spends its riches and resources on mental health and particularly on children, making sure they are loved, nurtured, yet independent, and have all of the coping skills needed. We are now in an era of record kids in foster care and, as we know, childhood trauma is a thread that runs through folks who suffer with Substance Use Disorder. So first order for a healed Appalachia would be a widespread movement and budget shift to help kids in trauma now.

A healed Appalachia is one that has abundant opportunities within a clear line of sight for everyone in the community. A healed Appalachia gives everyone a seat at the table regardless of their past.

I’m a big fan of Brad Smith, who along with John Chambers and others, helping launch and rebrand West Virginia as the start-up state, where we create a really robust small business economy that allows folks here to dream big and launch those dreams here, like Ian, Tyler and the WhizzbangBAM team have done in Huntington, building out a business that builds spiderwebs of creative economy supporting regional musicians and artists.

A healed Appalachia has ample and good-paying sustainable green-energy jobs that pay a living wage and that brings wealth and health and that are not destructive to our beautiful Appalachian Mountains and to the workers.

A healed Appalachia is one with nature, gardening, exercise and healthy lifestyles that bind us to our beloved mountains and valleys.

A healed Appalachia talks less about politics and more about community and being a good neighbor – as the wonderful new Tim O’Brien song, “Cup of Sugar,” suggests we should do.

A healed Appalachia is full of true forgiveness, grace and second chances for folks, making forgiveness not just an often-trotted out word in a book but something real and necessary to heal our communities.

I think that’s probably enough healing or I’ll have to send you a doctor’s bill… [Laughs]

(Editor’s Note: Read part one, our conversation with Hope in the Hills board vice president and WhizzbangBAM founder Ian Thornton, here.)

Photos by Hunter Way / Impact Media