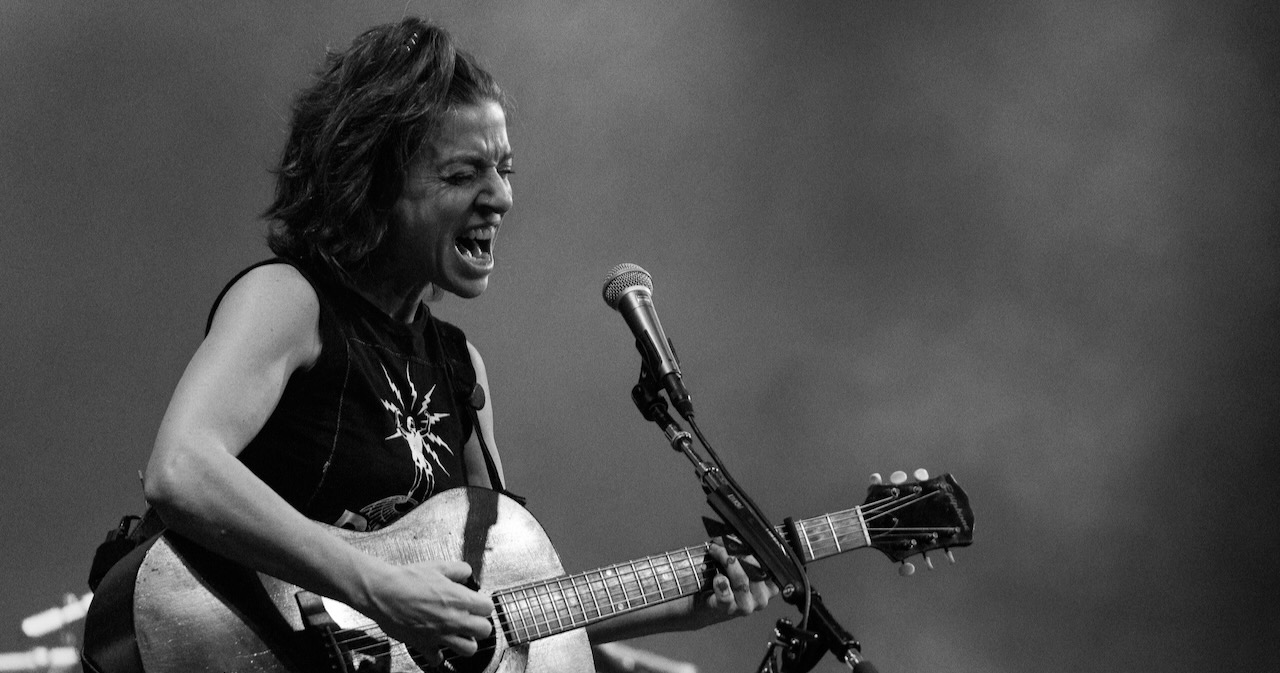

Dar Williams toured a spice farm in Belize amid pristine jungles and primordial Mayan ruins. At a bumpy junction, the driver told the passengers that there were three possible options: steering east, veering west, or sticking to the middle road, which he called the Hummingbird Highway. The instant wholly seized Williams’ attention. Something about the trail choices resonated, especially the enticing description of the middle one, striking her as a vivid metaphor of human life.

Williams, one of folk music’s most cherished gifts, titled her newest LP Hummingbird Highway (her 11th album). It’s an homage to the interdependence of boundless getaway and eternal return and another impressive offering from someone whose heart first journeyed to music long ago and whose emotional vigilance and poetic vigor seems to only intensify with age.

Indeed, the more Williams thought about the variety of roads, the more similarities she hit upon between herself and the hummingbird. “Hummingbirds have these fantastic migrations and hummingbirds need constant fueling,” said Williams.

Shortly after her Belize trip, Williams met a woman who had a matching hummingbird tattoo with her daughter, which the woman described as symbolic of distance and closeness, departure and arrival, the desire to fly in each and every direction with an understanding that the lucky ones can always ground again at home. Williams treasured the richness of all of this imagery. Once again, she contemplated the hummingbird, finding scores of analogies to the human experience and extracting her own correlations.

“Curiosity, love, longing, we’ve got all of these ways of getting around,” she said. “And it’s not always going forward. Like an artist, the hummingbird goes upside down and goes inside out… Flexibility, creativity, fastness, travel – they all make for a complicated person and parent. Hummingbird Highway was written from the perspective of a child, one with a peripatetic, depressed – perhaps bipolar – frenetic, creative, generous, loving parent.”

In a recording career that began with a demo tape in 1990 titled I Have No History, Williams has long leaned on songwriting and other forms of writing (she has written several travelogues and non-fiction books) to cast off and expose her blood and beauty to the world. Her creative journey was nurtured early in childhood bolstered by the support of parents who, as she said, “leaned into the commons culturally.” Born and raised in Westchester County, New York, music was always in the air at home. So, too, was love and praise.

Her mother was a preschool teacher who believed in letting her students and children choose their instruments first and then take lessons to learn how to play them, not the other way around. Her parents always backed their community’s arts programs, on one occasion selling grapefruit to raise funds for the local orchestra.

“I think that that influenced my love of working with coffeehouses,” said Williams. “It has influenced my love of things like art spaces that somehow figured out how to run a complex sound system, places that were community crowdfunded by a bunch of people who retrofitted it themselves from an old shoe store.”

Most of the music shaping Williams’ preferences she first heard long ago in her parents’ vinyl collection. At age 17, home from school one afternoon, she pulled out a couple of Judy Collins’ records. She fell in love with Collins’ Wildflowers (1967), which featured powerful orchestral arrangements by Joshua Rifkin and included her nourishing tone on songs by Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen. She remembers lines to “Sons Of,” a track from the 1970 album Whales & Nightingales as if she had just heard them moments ago.

“On these two albums by Judy, there were songs about lost sons and going to war and never coming back and brilliant, classical arrangements by Rikfin. There was poetry, peace. Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen, Jacques Brel. A song with whales in it… Music made around that time, the musicians literally considered themselves to be turning the wheels of life and death, of culture and civilization. I wanted to be a part of that fabric.”

Williams treasured the pomp and flaming fire of Marvin Gaye, his charged, sexualized characteristics, and his Motown expression, as well as his connection to the wider world of society and humanity. Because of him, music became more to her than just what was present in her home and town. Music could represent the fullness of the planet. She was no longer merely listening to voices and sounds, but comprehending human dignity. Simon & Garfunkel were key early influences, too.

“Paul Simon’s iconography of urban life and ordinary things, buildings, people, and food, influences me to this day,” she said. “The idea of trying to create a sacred landscape from our daily lives comes directly from Simon & Garfunkel.”

Hummingbird Highway is classic Williams, a fresh supply of drink from the ever-flowing spring, exemplifying all of the strong points that make her music enjoyable. Spot-on humility supplies the nourishment of every song. Some express gladness, some are heavy, some are weightless, and others reflect her attempt to reconcile everything in her person. Breadth and beauty reside in all of them, displaying and epitomizing a songwriting mantra that Williams has practiced for a while, which is to allow each song the latitude to grow and shine on its own terms.

“My personal motto is to stick to writing the song that you are writing,” said Williams. “You shouldn’t just bat away a perfectly delightful song about a dragonfly landing on your shoulder, right? You can get to the bottom of a song whether it is a lighthearted or not-so-lighthearted song. Just keep yourself in the shoes of the characters, and find out what’s really happening. Songwriting is committing to the world that you find yourself in.

“We go to music that makes us cry, helps us laugh, helps us bang our heads around and makes us forget things, or makes us be in the ecstatic moment and escape from the murky depths. Feel that first inspiration and keep on going. It ends up being deeper than you thought anyway, even if it’s a flaky song. It’s a way into your inner blueprint and there is a reason it surfaced at that moment. Who are we to say what’s deep and what’s not deep?”

Williams doesn’t journal or write every single day. She does, however, seek to be inspired daily, constantly looking for something surprising or special in the ordinary flashes of day-to-day life, a need that she can satisfy sitting at a museum or on a park bench.

“That’s part of the honest struggle between pedestrian things and poetic things,” she said. “The artist decides all of that on a personal level and decides what in their life it is that they would like to turn into poetry.”

The deeper that she dips into her career, the more that Williams realizes that there is a holy motion guiding each and every recording, pushed forward by an intention that’s both specific and accumulated.

“Music is like archeology, where there are a lot of layers,” she explained. “And each album is a layer and an album is an eon of my life. Looking back, I can pinpoint times of my life, depending on what album I was writing or touring with, and what issues were coming up. Like archeology, it all sort of seems to make sense in its own world, even though it doesn’t at the time [the album] comes out. There is a certain palate, a certain feel, a certain personality, and a certain neuroses attached to each album. It is another way to keep a chronicle of a life and another way to gauge a life.”

Many of the songs on Hummingbird Highway were written during the pandemic and hold numerous references to birds, indicative of a point when Williams spent hours alone staring at and refilling the bird feeder in the garden. There’s also “Tu Sais Le Printemps,” a French bossa nova tune, and “All Is Come Undone,” a piece of writing which came to Williams as she was breaking up earth in the backyard, attempting to convert an idle plot of dirt into a thriving meadow, listening to Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Later Autumn.” Williams’ stab at modern Americana, “Put the Coins on His Eyes” was inspired by the storied history of early labor unions, movements, and revolutions in the U.S., and all of the agitation, suppression, and violence marking their expansions and downfalls.

The joy of taking a batch of new songs on the road is still compelling to Williams, who approaches every night with an alchemist’s urge for transformation, worship of experimentation, and spiritual curiosity about the core quality of things.

“It is a great thing to walk out and feel the energy of the people,” said Williams. “It’s best when there is no skepticism and no suspicion. But some audiences are tentative. You can feel it within the first couple of songs, like a massage therapist who feels tension; you feel the accretion of awareness for what kind of energy field you are walking into. The goal is to get to another place musically together with the audience.”

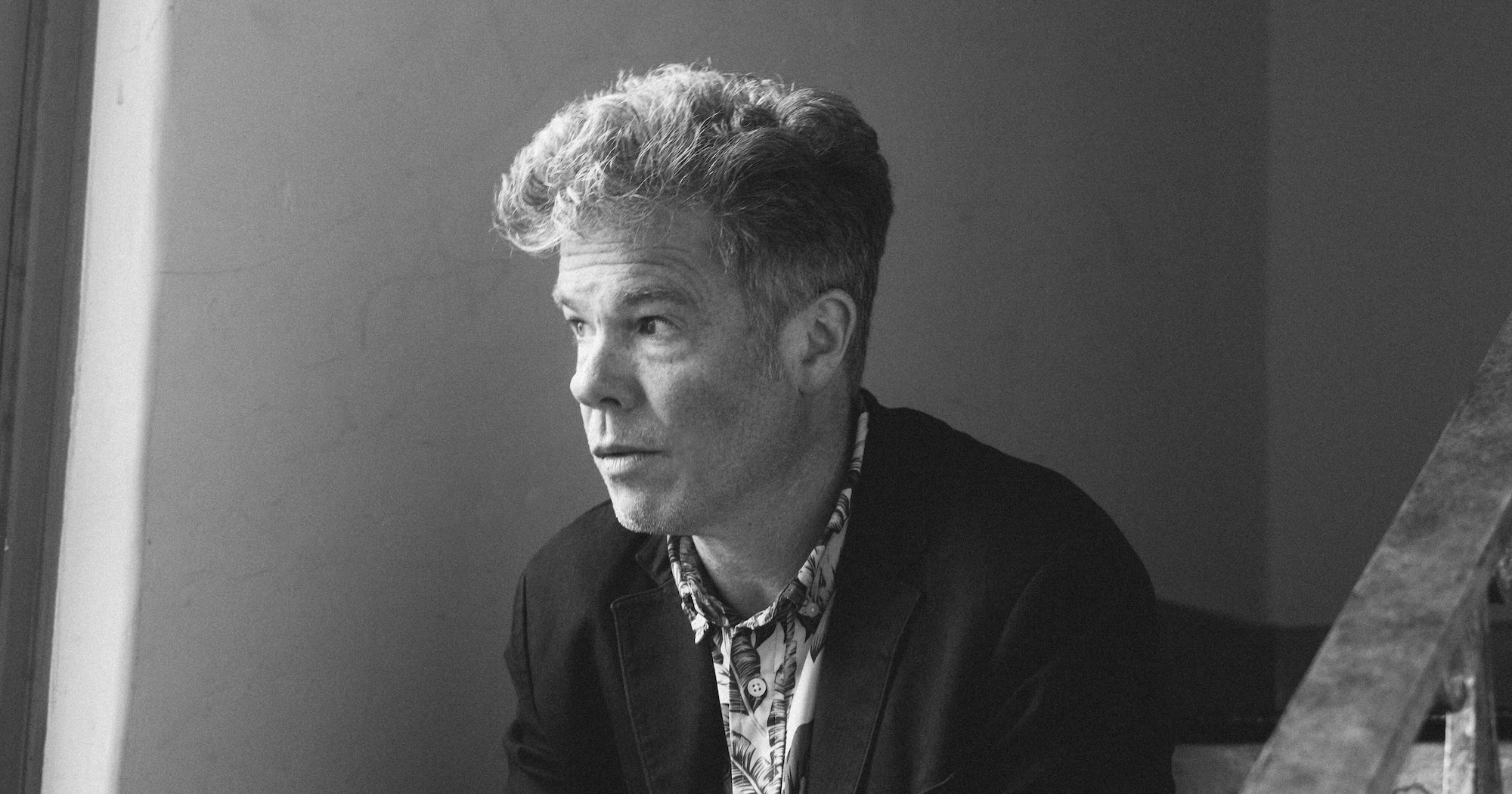

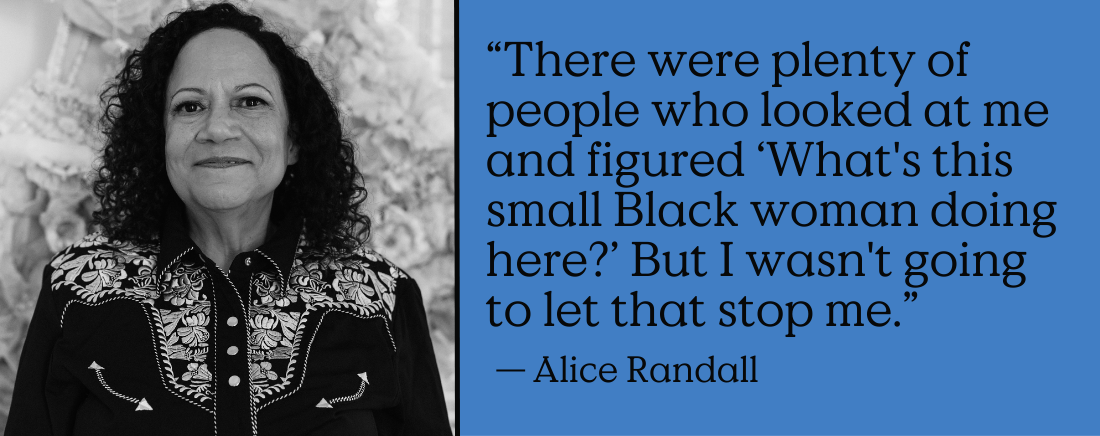

Photo Credit: Carly Rae Brunault