Stelth Ulvang is a storyteller, but as he shares in our conversation, if it hadn’t been for a broken mast on a famous sailboat years ago, his stories might have found a different outlet than music.

Since then, his musical life has unfolded from one wave to the next. From playing with established bands like The Lumineers or his own projects like Heavy Gus to finding pick-up bands in different towns, he is fast and prolific. His latest effort, Stelth Ulvang and the Tigernips, is a ten-song opus, cut in New Orleans by The Deslondes (a band he indeed met through a friend). A self-declared autumnal record, Ulvang grapples with death with a lilting cover of Echo & the Bunnymen’s “Killing Moon” and guides the listener along his travels in “What Three Dogs.” The (mostly) live recordings lend themselves to the raw emotion of the storytelling.

BGS spoke to Stelth Ulvang over Zoom from his home in Bishop, California.

How’s your life?

Stelth Ulvang: Well, we just got back from a family vacation, and our 3-year-old hates us for trying to explain jet lag to him.

It sounds like you were on a real adventure. Where all did you go?

Greece, Turkey, and the Republic of Georgia. We have a friend there that is a wild, wild, Wild West woman.

She won this great horse race, and she’s really into cooking over big fires. She won the Iron Chef competition there. She’s a pretty versatile human, but pretty wild. So it was fun to have a friend in these places. We had friends in Greece and we had friends in Turkey. But we didn’t have instruments. My wife and I play a lot of music together, so we’ve always traveled with instruments, and this time we refused to.

I’ve just been recording all last year. I’m sitting on three records of recordings and trying to just put out one of them right now.

Nice. That’s awesome. Do you write alone, or do you and your wife write together sometimes?

I normally write alone. I have a hard time writing with others. I just haven’t had enough practice with it. With our other project, Heavy Gus, we will bring songs to the table and then we’ll intermingle and edit them together. But for the most part, it always comes from one voice or another. We haven’t sat down and said, ”Let’s write a song.” I find it harder. It’s more vulnerable than the other parts of a relationship, I find. After like sexual or intimate vulnerabilities, I found writing music together was like by far the last tier.

Well, not to make it about me. But I write music with my husband. Co-writing and the kitchen are the only places we fight.

Oh, yeah, totally. It can get really impassioned. You are just opening yourself up on the table in this way, and it can just go so quickly to feeling under attack about this very personal thing.

You’re very prolific. Sounds like you got a lot of stuff in the pipeline to release.

When The Lumineers stopped touring, I kind of just rallied and tried to get everything done. I did a lot of the writing on the road with the band. There was a lot of downtime in hotels. For a long time, I was recording in hotel rooms with my phone on voice memos and stuff like that. But then I got into using Garageband on my cell phone and making more produced tracks. I released a record like that.

Ultimately, I found that my favorite thing to do was to find a band. If we have a few days off in a town, I find a band and go into a studio somewhere and see if we can just record five tracks. So that’s what I kept doing around the States during this Lumineers tour for the past three years. I had written all these songs over COVID. So we’d be in Cincinnati for three days and I’d find a band and record five songs.

When you say “find a band,” what do you mean?

I mean whip a band up. Ideally, find a band that plays together and they’re down to just like learn a song of mine.

Are you meeting them at a show or are these people that you’re like friends of friends with online?

Yeah, sometimes friends of friends, people that I’ve never played with. But for this record, Stelth Ulvang and the Tigernips, this is all people that I had never met. A friend who was going to be on the record but then left for a tour was like, “Well, they’re good people, you’re in good hands.”

It was fun to just use real old gear, old vintage mics and run it all through tape. We recorded everything live. Singing it live, that’s something I’m not as used to. But with this band from New Orleans, the magic was quick to come.

Did you know you wanted to cut it to tape before you headed down there? Or was that circumstantial?

That was circumstantial. It’s funny with tape right now, because obviously, everything just gets digitized. I was trying to think, “Is there a way that we can keep this off of ever touching digital?” And it’s almost impossible. You know it’s possible, but it feels impossible.

With the record I made on my cell phone, I only released it on cassette tape for a while, which was the reverse. So I should have tried to be true to form and release it just on vinyl and tape in analog form. But it’s 2024.

Well, tell me about self-releasing music. What does that feel like in 2024?

It’s like I finally figured out the releasing stuff. I’ve had help through Emily Smith, with the Alt-Country Show. There was a lot of logistical stuff that I was getting new anxieties about – a lot of social media.

You think you have it all figured out and then it’s just all about being a content creator. I feel like an old man. It’s so complex, but it’s true. I finally kind of figured out how to self-release and self-book shows and now that almost feels like an obsolete skill set. I’m doing a whole tour around the Northeast on this record for a few weeks and booked everything myself. Amazing that it like came naturally, just writing people and asking for help. But yeah, the content is a skill set that I forgot to put my 10,000 hours in on.

I feel that. For the tour, is the band that played with you on this album from New Orleans going?

No, they’re all gonna be in Spain at a sick residency that they do every year. The band goes to Spain once a year. They’ve done it for 3 years. Now this will be, I think, their fourth year. And there’s a huge following in Seville of American country and folk.

It’s interesting that country music is getting big. But in Europe right now, it’s getting huge and friends who do country tours in the States are having much more success in Europe right now.

It also feels like the genre is broadening. There’s obviously the stuff at the top of the pyramid that, depending on your ears, can be exhausting. But there’s more room for more kinds of country.

In that realm, I don’t know that I like the song for what it is, but “Old Town Road” by Lil Nas X – to have a gay Black man put out a track at the top of the country charts, I think opened up the the floodgates to be like, “Anything goes.” I think that is an extraordinary gift to any realm of music, to do something so left field and find success for it. So bless Lil Nas X for that and maybe only that.

What’s a Tigernip?

What is a tigernip? I don’t know. I forgot. … I was just trying to think of something that wasn’t a Google trope. But I wanted the combination of very quick, ferocious, and sweet. We recorded half of the album in the space called the Tigerman Den so I was starting to call it “the Tiger Men.” But there were women in the project. I think I said “Tiger Dicks” at some point, and everyone was like, “What the hell is wrong with you?”

But then, something about a tigernip kind of sounded like a tiger lily or catnip.

I wanted it to be clear that the band that recorded on this record was actually a band and it wasn’t me just doing like solo songs. And how much the album was influenced by these relationships that we had over a very short few days. So, that’s why I was really set on trying to find a band name for us.

There’s a frequent revisiting in the songs on this album to the theme of water. And I read that at one point you sailed from Hawaii to Seattle. Since you have this connection to water, I’d like to know about that sail and if you have an everyday connection to water?

It’s funny, I don’t necessarily buy into astrology, but being an Aquarius, I am appalled that it’s not a water sign. I feel completely more watery than airy. [My birthday is] the very last day of Aquarius before Pisces, which is a water sign. So maybe that’s why I’m compelled to lean into the water sign. And my Chinese zodiac is the tiger.

Back to the sailing trip! I did not want to play music before this time in 2008. I met this musician who invited me on this sailing trip and I just wanted to go on an adventure.

Meaning you didn’t want to play music in your life, or you needed a break from it?

I was playing in high school and I tried to go to college for it. I didn’t like it and I dropped out. I just wanted to travel. I had gone on a bike trip, I was hitchhiking a lot, and I was riding trains everywhere. If music could help me travel, I was open to it.

I traveled to Hawaii to pick up this boat that was famous in National Geographic because of this teenager, Robin Lee Graham, trying to sail it around the world in one go. He left his boat in California and it got moved to Hawaii. I had somehow signed up with a buddy that I barely knew to travel with this boat from Hawaii up to Bellingham, Washington, where it was going to sit in a boat museum for its historical significance.

At the time, this was the youngest boy ever to sail around the world alone. The record has since been broken by a young woman. [The boat] had so much repair work that had to be done on it. So we’re in Hawaii for like five weeks, during which I got arrested for shoplifting some food at Sam’s Club, because we’d run out of all of our money that we had saved up to do this journey. I decided, “Screw it. We’re we’re just gonna skip the court date, I’m gonna get on this boat and we’re gonna sail.” So we bail on this court date, establishing a nice bench warrant that I had to deal with much later on. We make it a week out and the mast busts, and we had to get rescued. And I have never sailed extensively since then.

While we’re at sea my buddy had this mandolin. We sit there, and we’re just trading verses back and forth, writing this kind of silly song as this joke idea that we’re these stranded pirates. We’re just coming up with lyrics. We get towed back to Hawaii; I was really nervous about going to jail. We go to the airport and beg these flight attendants to basically put us on standby to get us back to the States. The only flight that they could put us on was one that went up to Seattle. We’re like, well, “We can hitchhike home from there.”

So, we go up to Seattle and we have no money, not even bus fare, to get to my friend’s house that lived in North Seattle. So we sit in the airport and we play this song, making up words on this mandolin with a little hat out [for tips], just for bus fare. As soon as we get the bus fare, we leave and we’re at our friend’s house. We tell him the story and he’s like, “You know, we’re having a show tomorrow night. You guys should play your song at this show that we’re having in our basement.”

That was the first show essentially that I ever played. By the end of the trip, we traveled for another couple of weeks back to Colorado, we’d written an entire album’s worth of stuff. As soon as we got back to Colorado we already had a band name. We had all the songs ready to record and all of a sudden I was a musician again.

Wow! All because of a broken mast. That’s wild.

SU: The boat was called the Dove. And the book that was about the boat is called Dove. So we called our band Dovekins. Never looked back.

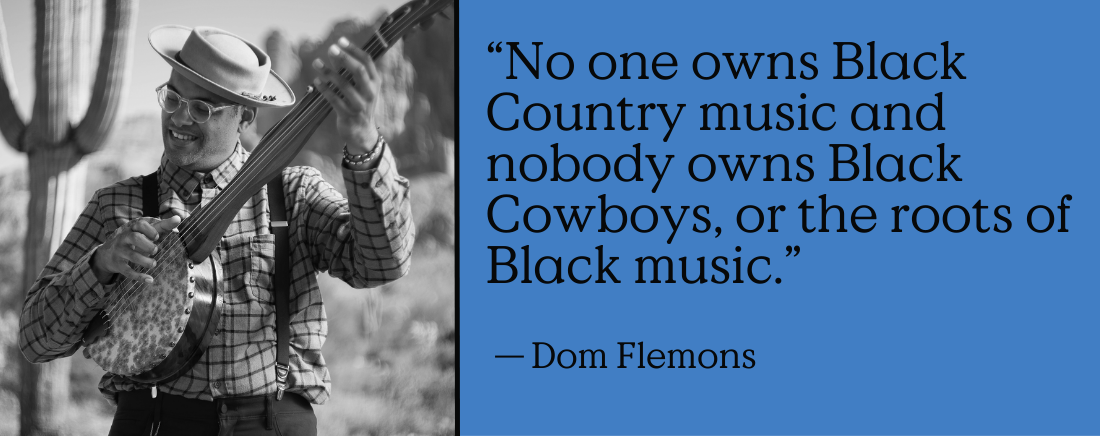

Photo Credit: Rachel Deeb