Nashville business owner and frequent BGS collaborator Maria Ivey apparently didn’t have enough on her agenda when a tornado hit Music City in early March and the music industry subsequently shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s the moment when she started quite the gargantuan project — a community cookbook.

All the Thyme in the World features scores of recipes — soups and appetizers, sauces and mains, desserts and breakfasts — from the aptly described “grounded” music industry, which includes a true cross-section of musicians, performers, touring professionals, industry experts, writers, designers, and so on.

The volume leans into the homespun, down-to-earth charm of DIY community cookbooks common in the South and across rural America, taking wisdom from lovable food nerd Alton Brown himself, as referenced in the foreword:

“First, such books must be spiral-bound or they are not to be trusted. Second, all recipes must be directly attributed to a member of the community. Food is mighty personal, and the sharing of a recipe, especially one that may have been polished and perfected through years of practice, is powerful medicine. Third, community cookbooks must be truly democratic…”

Not only is All the Thyme in the World democratic, powerful medicine, mighty personal, and yes, spiral-bound, its profits will support the vital work of the Music Health Alliance’s COVID-19 & Tornado Relief programs. The first pre-order period closes June 1. Music + food fans are encouraged to order now to make the first printing.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-0UARbBex4/

BGS connected with Maria Ivey over email to discuss the project and give a sneak peek at a couple of the recipes.

BGS: A deadly tornado hit Nashville in early March, barely preceding the coronavirus pandemic, so “disaster mode” here has been going on a little longer and has been a little more intense than in a lot of other cities — and you still added this project to your plate! Why is it so important to you?

Maria Ivey: We have to take care of each other!! If we want to believe that the music industry will snap back after some semblance of normalcy returns, we have to ensure that aid is given to keep creators creating. Music Health Alliance does just that. The idea for this cookbook came while I was sitting at the kitchen table, staring down the future wondering what the hell I would do with my hands and all of this time. I sent a few late night emails asking foodie music friends for recipes and help, which were then forwarded to other folks — some I knew, some I didn’t. While I was writing press releases for countless festival cancellations I was cooking nonstop. Three meals a day, sometimes four, crowding the fridge with leftovers and feeding the excess to the dog and chickens. Partly because staying home was the right thing to do and partly because I had to do what my bones told me to do.

Proceeds from this cookbook will go to Music Health Alliance’s COVID-19 & Tornado Relief Program. I have personally witnessed the good this organization does for our musical community and am honored to aid their efforts with this cookbook.

Why do you think musicians, creators, performers, and folks in the industry responded in such numbers? What is it about cooking and the kitchen that makes them so closely intertwined with music?

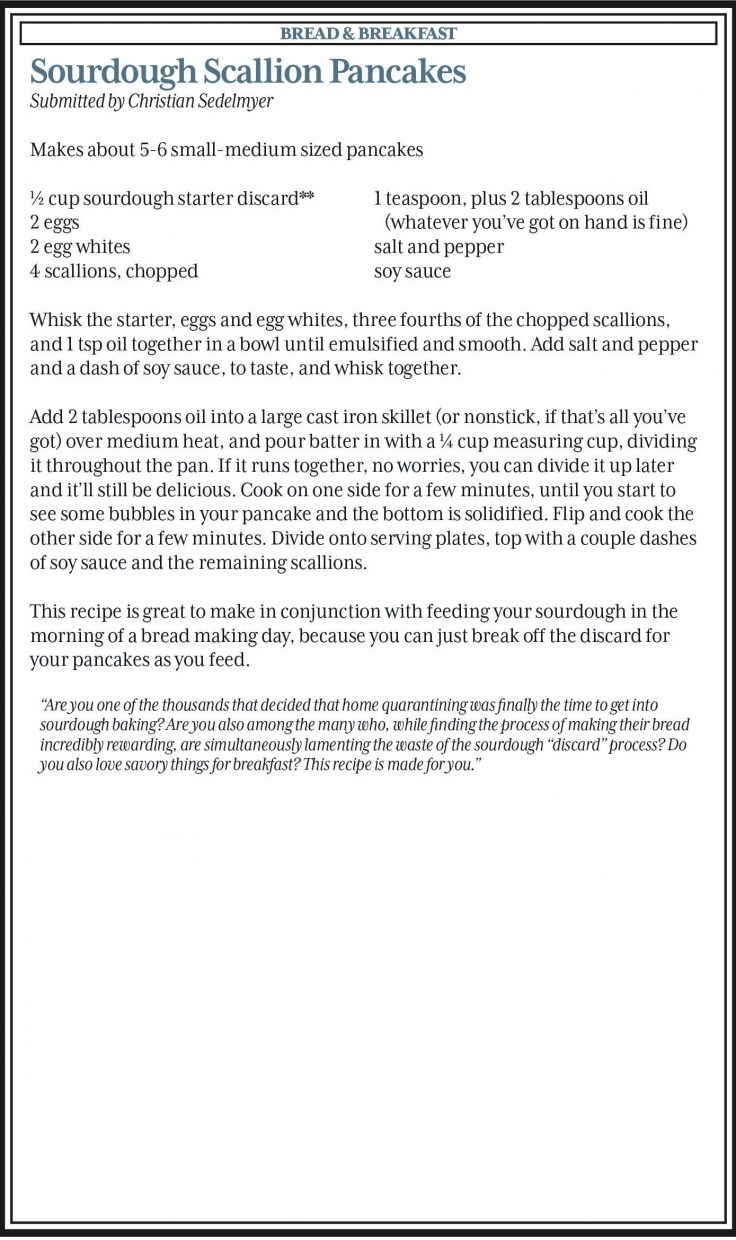

Cooking and music are both creative endeavors. It makes sense that some of the best songwriters or musicians I know are also the most interesting cooks. For example Christian Sedelmyer is a monster musician, but he’s equally capable in the kitchen, probably because he pays attention to flavors and knows how to make ingredients compliment each other. Not unlike what he does with the fiddle.

Inside you’ll find recipes from journalists and photographers, publishers and interns, a drum tech for arena tours and a tour manager who always drives the late shift, songwriters and banjo players, festival producers and super fans, a beloved Nashville guitar shop owner and The Late Show’s band leader, Bowie’s bass player and a Grand Ole Opry host. And Dolly Parton. I chose to leave off job titles and places of employment because none of those labels have a bearing on how food tastes.

The cookbook is an incredible way to visualize the community we all have surrounding us (myself and BGS executive director Amy Reitnouer Jacobs both submitted recipes as well). What have you learned about this community that has surprised you most?

I guess it’s not really surprising, but I was reminded of — floored by, even — how willing folks are to help each other. People I have never met volunteered to help me format recipes. My neighbors, all involved in music in some way or another, offered to help ship out books once printed.

Gena Johnson emailed something like 50 people for recipes. Shelly Colvin, too. Both blasted the recipe request to god knows how many people helping to fatten the book up. Journalist and editor friends, like yourself, emailed me asking how to best spread the word. Grant Prettyman immediately jumped in to design the cover art and layout, citing his Atlanta upbringing and his mother’s collection of Junior League cookbooks as inspiration for the aesthetic.

A quick Google search led me to Pollock Printing, a third-generation family printer in Nashville. I had a long and happy conversation with the owner, John Craig — someone I’ve still not met in person — who knew several of my clients and told sweet stories of his dad leading bluegrass jams. Dacey Sivewright, a friend [and BGS contributor] who has been writing about music for over a decade, reached out to offer help editing the recipes. I stopped saying “I” and started saying “we.”

Then we had 100 recipes. And then 200. When the website went live, orders poured in from people I had never met and from places I had never been. My brother ordered 15 copies. I cried. And just like that, the world didn’t feel so scary and I didn’t feel so alone. We didn’t feel so alone. Apart, yes. But not alone.

You must be so excited to get to tasting these recipes! Have you tried any yet? What have you tried and what are you excited to get to cooking?

JoJo Hermann (keys player for Widespread Panic) submitted a family recipe for whole bird “Vinegar Chicken.” I tried it a few weeks ago and it was incredible, the vinegar marinade takes what can be an otherwise bland protein and made it interesting and punchy, and the skin was super crisp. I made broth with the leftover bones. I laughed because he submitted the recipe and then his sister emailed me to make sure everything was correct. Definitely something that would happen in my family.

Marshall Chapman sent in “Pork Noodle Soup,” a recipe she adapted from the New York Times. I made it on one of the colder days in March and it was instant warmth (fresh grated ginger and garlic) and comfort (rice noodles and pork fat). I haven’t made Jon Batiste’s recipe for “Katherine’s Red Beans,” but it’s on my to-do list for this weekend. Everyone I know who is from New Orleans is an excellent cook so I’m excited to try his take on this classic.

And there must be some Ivey family recipes in the mix as well?

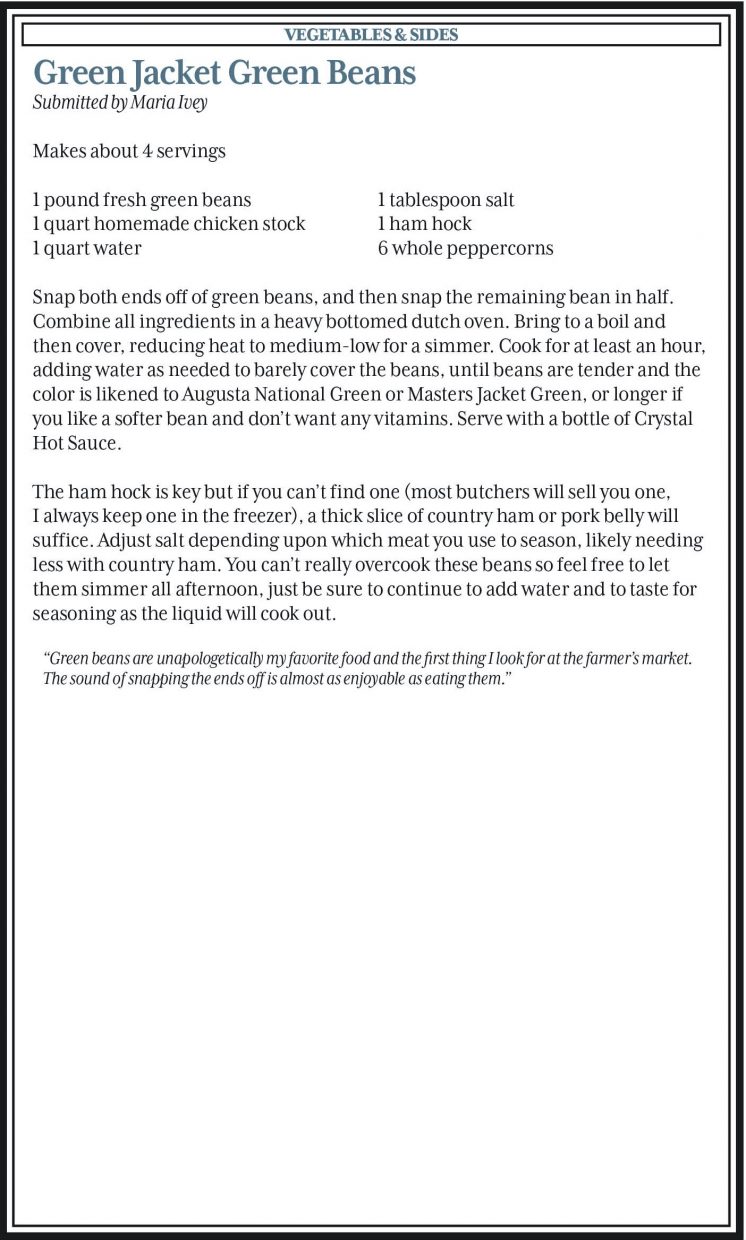

Yes! I gave a recipe for “Green Jacket Green Beans” (when the beans turn Augusta National Green, they are ready to be eaten) and my husband, Taylor, put his “Sunday Morning Biscuits” in the book. I’m partial, but they are both excellent, and easy! Salt and fat. Always. I’ve been known to order a side of green beans with my biscuits and breakfast at Cracker Barrel, so it’s fitting that these recipes are our contributions.

I’m glad to have had a reason to write them down. Several people said that about their recipes, too — thanking me for giving them a reason for writing down whatever their famed dish is, getting specific with measurements and ingredients. We have to archive this stuff! It’s so easy to Google for a recipe but I’d like to see a return to cookbooks, community cookbooks in particular.

Let’s make it painfully clear for our readers before we go — how can they support All the Thyme in the World?

Pre-order here before June 1 to be included in the first print run!

Photo credit: Melissa Madison Fuller