Dave Simonett has proven himself to be a man no genre can hold. Some days the Minnesota-based singer/songwriter is fronting prominent Duluth string band, Trampled by Turtles. Some days he’s playing with a full rock band behind him as Dead Man Winter. Now his latest project comes in the form of his first full-length solo album, Red Tail. In a phone conversation with BGS, he discussed his freedom from expectations, the project’s emotional clarity, his love of musical diversity, and more.

BGS: Tell me about making this album. What’s memorable or special about it for you?

DS: Well, I started out just making it by myself. That was kind of what I had in mind for the whole thing, initially. I have a studio in Minneapolis and I was working there. I recorded pretty much all of the songs that ended up being on the record and thought I was done, but at the end of that process I thought I’d like to expand a few of them with some other players.

So I ended up going down to Pachyderm Studios outside of Minneapolis with a small band and re-recorded about half of it down there. Still used some of the stuff from my studio, some from Pachyderm, and just kind of smashed it together. This happens to me pretty often. I’ll have what I think is a concrete idea of what I want to do at the beginning of a project, and then it evolves from there. I’ve learned over the years to let that process happen.

You mention that Red Tail benefited from a freedom from expectations because you recorded it without really knowing if anyone would ever hear it. How do you think that freedom helped flavor the album?

I do think there’s a freedom to that and I think it’s the first time I’ve ever done that. Normally when I started to record anything there was an end product in mind: “We’re going to go make a Trampled by Turtles record,” or something like that. That carries with it a certain amount of pressure, which this didn’t really have. I just had these songs and I wanted to record them. I didn’t know what it would be, I just wanted to record them. So I had a little bit of time on my own doing it, and then I thought, “Well, let’s see what they sound like with the other people and a little bit of time in the studio.”

The whole time I was thinking, “You know, this could be something or not. Maybe this is just demos for another band.” But as the process went on, it started to fuse together into something that felt like a record to me. It ended up being a really easy and natural feeling, and that came from the thought process at the outset when I thought, “This doesn’t have to be anything.” I didn’t have a deadline. I didn’t have anything like that. It was really open, and in a weird way it took away a lot of stress.

From the point that you realized this album was something that you’d be releasing, did the songs change in any way from an arrangement or textural standpoint?

Yeah, definitely. Both of those. They even changed from a lyrical standpoint, and I think that a lot of times when I’m working on a record it will do that throughout the process. It’s something as simple as adding some different people in there. That in and of itself just changes it so much.

We recorded everything pretty much live, which is how I generally like to work, so there wasn’t a whole lot of forward thinking in that way. It was more like, let’s get these guys in a room and see what happens when they play the song however they feel like it. And then maybe a couple little adjustments, but that was really all of the arranging we did. Just the fact that there were other people contributing stuff from their own creativity was enough to change it quite a bit.

You say that recording this album was the best you’ve ever felt in your personal life while recording. Do you think that helped give you the clarity to better examine some of the darker subject matter on the album?

Yeah, and I generally get the same vibe from other writers that I’ve talked to. I think that maybe depression, or hard times in general, get a little bit romanticized in music. It might be like the whole Townes Van Zandt myth or something like that; that you have to be super messed up to write music. In my life, in periods where I’ve been like that, I can’t make anything. I feel like creativity and the drive to go make something are at their peak when I’m feeling good.

I think that’s a pretty simple equation when you think about it. Sometimes it’s hard to get out of bed, let alone go to a studio and write all day, along with all of the stuff that goes into making a record. I do think that “clarity” is a good way to put it. Everybody has rough patches in their life. Being at a point to look at some of those and examine them, I think the best way to do that is from a different place. For me it is.

A healthy mindset keeps you from being sucked down an emotional rabbit hole that can end up impacting the entire album and recording process.

Yeah, that’s a good point. You can look at it and almost have a sense of humor about it instead of taking it, and yourself, too seriously in that subject matter.

You talk a lot about how special it is when the listener can apply a song to their own life. At the same time, this is your solo album and sort of a vulnerable look into your life. How do you write in a way that’s specific enough for these songs to mean something to you, but also broad enough that any listener can apply it to their own lives?

I have no idea. [Laughs] I don’t think it’s very intentional. I feel like most of the time I’ll just write, and once in a while I’ll see a line and recognize that from some experience in my life. Instead of thinking about an experience and writing towards that, I just write and then I can look back on it and say, “Oh, I know what that was about.” Most of my work has been that way. It starts like that for me. It starts kind of ambiguous.

It all comes from inside. All the stuff that’s jumbled up in my brain comes out as this, so it’s by its own nature personal. I’ve never really been good at writing stories about things that didn’t happen to me. Some other people are really good at that, but I can’t do that. It all comes from me, but very rarely does it get very specific, and I think that’s just my general style. Maybe a comfort level thing.

“There’s a Lifeline Deep in the Night Sky” strikes me as one of the purest representations of the community and fellowship that surrounds roots music. For somebody who may not know anything about this music, what would you want them to know about the community that surrounds it?

I don’t know if I can think of anything that specifically applies to roots music. This might be a roundabout way to say it, but when I started playing music in Duluth with Trampled, and a couple other bands before that, the music community was really tight. It was also really diverse. There wasn’t another string band in that town. The scene was small and creative enough to sort of only allow for one or two bands who sounded similar, and then nobody else would want to start something like that because it’s already being done. So my sense of musical community comes more from the diversity of the scene.

[Trampled by Turtles] didn’t really start out in an Americana scene. We’ve grown in that world since then, but I think community applies to music in general. I think a lot of people divide stuff up into genres a little too harshly. The people who came down and sang with me on “There’s a Lifeline Deep in the Night Sky” were just a gathering of people who happened to be at the studio. These were people, a lot of them musicians and a lot of them not, who were from all over the place musically. It was more like, let’s all get in a room together and sing a song. I feel like you could probably find that in hip-hop, metal, or anywhere. I hope so, anyway.

I felt really lucky to grow up musically in Duluth in the early 2000s. Every show we played would be with two or three bands. It would be us and a punk band, a hip-hop band, a straight-up rock ‘n’ roll band, but we were all friends. It was celebrated that we were all different from each other, and that’s why we were all doing this together. That’s one of my favorite things about local music scenes across the country. Finding that stuff. You’re right, we do have a great roots and Americana scene around here in the Midwest, but there’s great everything. When people get too caught up in one thing it can get a little poisonous. I feel like music itself brings communities together.

Recording a song like “There’s a Lifeline Deep in the Night Sky,” we recorded it with one microphone onto a cassette player. It was about as informal and unrehearsed as it gets. It was just fun. Nowadays, especially with the modern recording process, it’s easy to make a perfect song. You can make the tempo perfect, the pitch perfect, and everything. Still nothing compares to getting a bunch of people in a room and playing a song live. Embracing the little imperfections that happen as part of the uniqueness of the recording.

Playing with punk bands and metal bands, how does coming from a place like Duluth impact your scope? Does coming from a scene with so many different types of music open your borders and give you some freedom to explore new ideas?

Absolutely. If nothing else, it helped me get out of my own head. If I wanted to go see some live music I would see so many different kinds of music. It wasn’t like it is in some places, where I could go see a folk act every night. I can’t go see a bluegrass band every night in Duluth. It forced me, and hopefully a lot of other people, to celebrate all these different bands.

To me, the genre doesn’t matter at all. A song could be on a banjo or a laptop, but if the song connects with me then I’m into it. I don’t really give a shit which instruments are played. It’s about the song, or if you can see some kind of art in the performance that you really connect to. To me, that’s the most important part. That’s what I want to celebrate. When I record, this is how I like to do it, but that doesn’t mean I don’t want to go see Atmosphere some time. Just because I can’t play that music myself doesn’t mean I don’t love it.

I try to be honest with myself in the recording process, where if something comes up that I want to try I’ll give it a shot. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. But to your question, I really am thankful for that diversity in my music growing up. That’s helped me keep an open mind. I feel like the older people get, and the older I get, it’s even more important to keep your mind open.

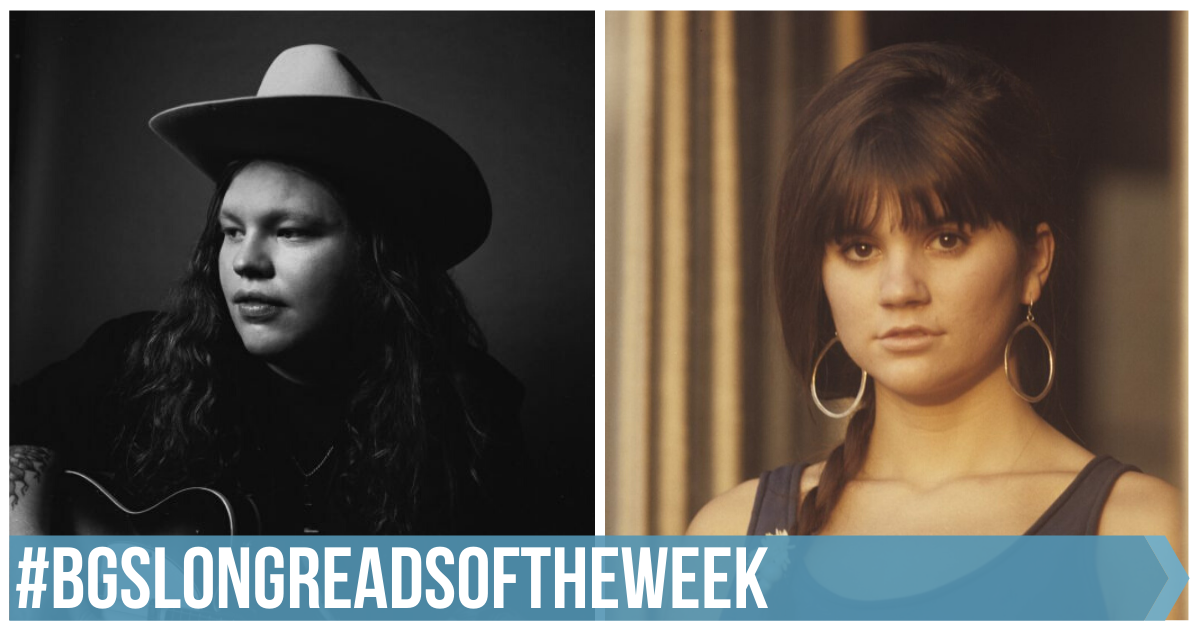

Photos: Zoe Prinds