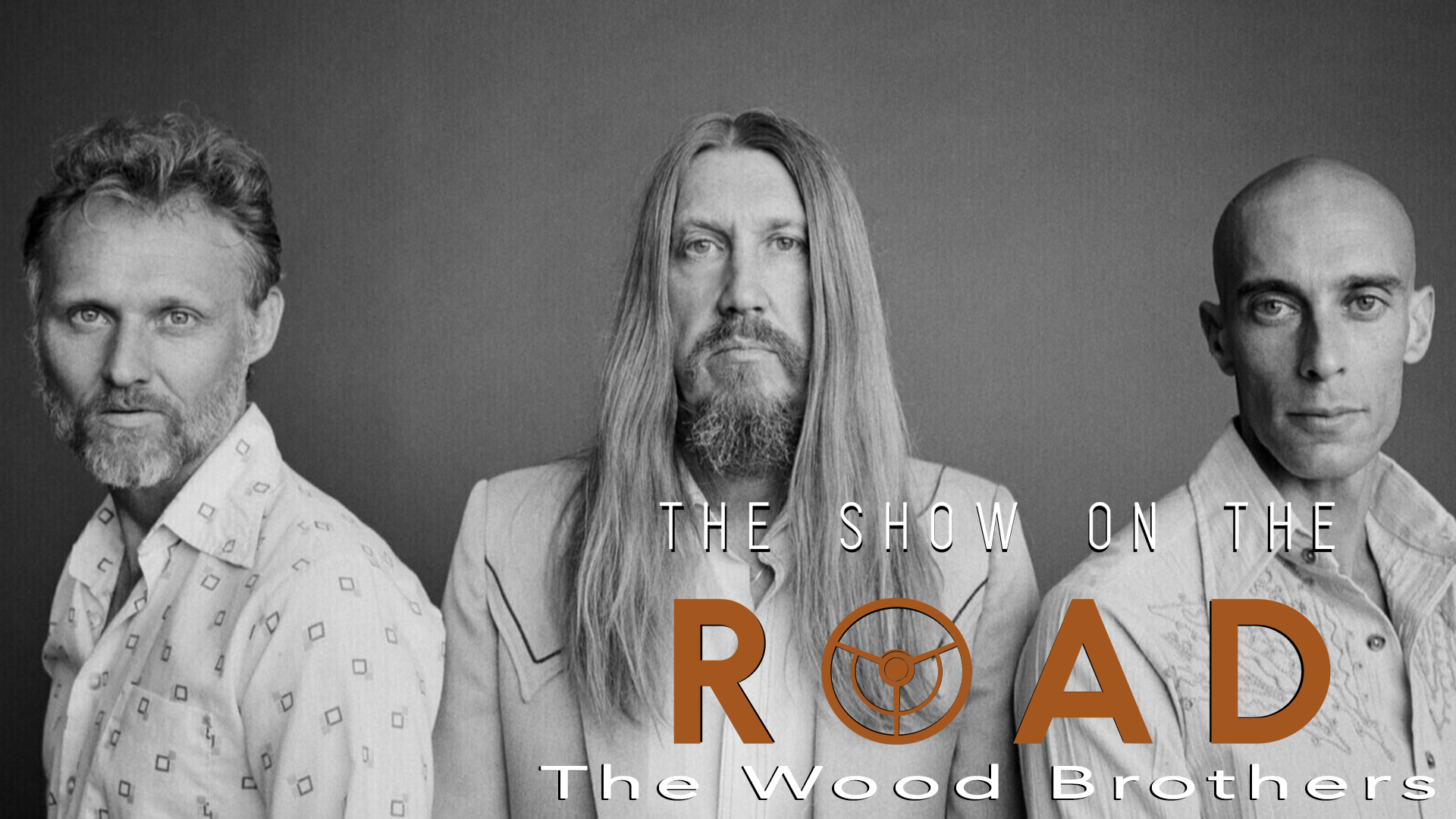

Artist: The Avett Brothers

Hometown: Concord, North Carolina

Song: “Victory”

Album: The Third Gleam

Release Date: August 28, 2020

Label: Loma Vista Recordings

In Their Words: “The Third Gleam was finished before a virus and its carnage swept through humankind in the spring of 2020. It was finished before the most recent injustices against Black lives inspired outrage and a much-needed call for social reform and revolution. Through the fever pitch of fear over the pandemic, outcry in the wake of widely observable bigotry, and mourning over the death caused by both, we are united in conflict… put to task in the arenas of our fortitude, our morality, indeed the strength of our own souls, individually and collectively. It is a time of heightened experience; heightened response; heightened resolve. If you are reading or hearing this statement now, you are a part of it.

(Editor’s Note: Read more from their statement below.)

“And yet, neither of these massive fundamental concerns are entirely new to us. Sickness… in body and in mind are old news for our species, and in truth have found us susceptible throughout our complex history. And so our plagues, biological, behavioral and systemic, are intrinsically a part of us. We navigate them poorly at times and heroically at others.

“To the point of this writing, as it pertains to the announcement of a record release, it barely warrants mentioning that an eight-song collection is a whisper of an offering in a time of blaring considerations. As I mentioned before, Scott and I finished this album just before these two fundamental concerns overtook nearly the entire planet. Consequently, as the timeline goes, the songs were not informed specifically by the urgent and pivotal concepts which are now center stage. However, as these factors have been and will remain a part of us as a whole, independent of a specific moment in history, the songs of this particular piece do connect somehow to this particular time. Our personal perspectives and experiences are inherently the common thread, which is an element we have found to be imperative in our process of making art. Even so, there are themes which have made their way into this chapter of songs that are undeniably universal, and anchored in our current world…

“Isolation, resilience, frustration, confusion, contemplation and hope are here, both in regards to our own lives and as a consideration of the human experience in general. There is humor and love, both for life itself and as it binds a pairing of people. We touch on historical prejudice, faith, economic disparity, gun violence, incarceration, redemption, and as is increasingly standard with our records, stark mortality. This is by no means a record defined by any specific social or cultural goal, nor is it informed by a singular challenge posed to humanity. It is merely the sound of my brother and I in a room, singing about what is on our minds and in our hearts at the time…sharing it now is about what sharing art is always about: another chance that we may partake in connecting with our brothers and sisters of this world, and hopefully joining you in noticing a speck of light gleaming in what appears to be a relatively long and dark night.” — The Avett Brothers

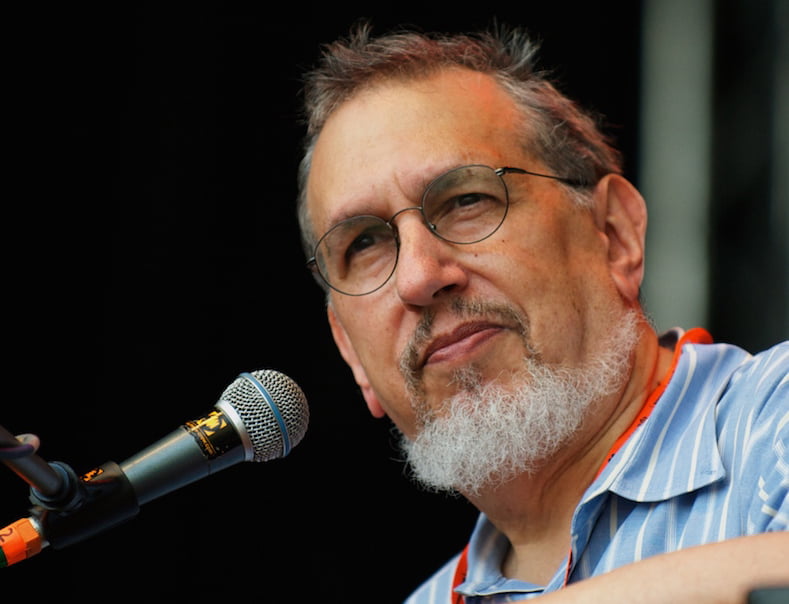

Photo credit: Crackerfarm