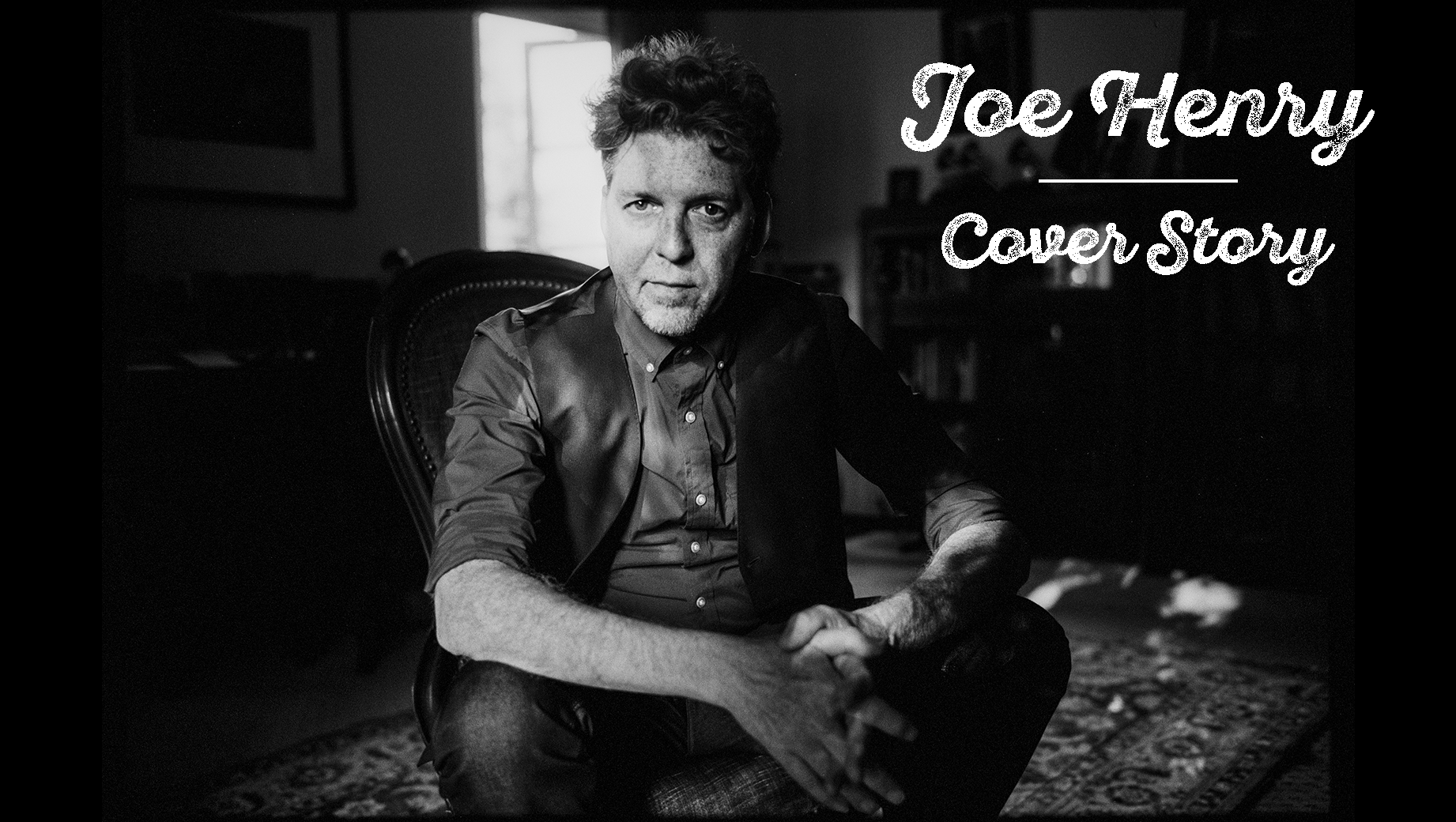

Joe Henry is sitting and chatting in the living room of his vintage, Spanish-style home in Pasadena, California. The subject of the note that starts off his new album, The Gospel According to Water, comes up. He looks over his left shoulder and points to the corner.

“It’s that guitar right there,” he says. “It’s an all-mahogany Martin from 1922. It was the first guitar they made that was created for steel strings.”

Seeing this small, plain instrument, it seems impossible that it was from this that he conjured the note in question, a sound deep yet brittle, intimately resonant. It’s at once ancient and fully present in the now. And it’s a sound that serves as something of a motif throughout the marvelously moving, affectingly poetic cycle of songs. It was a sound from a specific source that was echoing in his head when he sat in the Los Angeles studio of his longtime friend, recording engineer Husky Huskold, to set a new batch of songs on tape.

“I played him one song from Lightnin’ Hopkins,” he says. The song was “Mama and Papa Hopkins,” a 1959 recording from the point of view of young Lightnin’ getting his feuding parents to see the good they share.

“It was just vocal and acoustic guitar. And Lightnin’ is mostly singing to a single string that he’s playing. And yet the way it’s recorded, it’s so heavy. There’s such a sense of ominous space. And I said, ‘Look. I know I’m not him. I’m never going to be Lightnin’ Hopkins. But listen to what’s going on here. There’s something that’s making this so visceral in a way that I want to hear. Even if this is just demos, I want to hear a sense of drama.’”

You’d think Henry, who just turned 59 last week, would have had more than enough drama. A week before Thanksgiving 2018, he’d been diagnosed with prostate cancer, which had metastasized to his skeletal system. (He is in remission now and feeling hearty.) When he went in to record, it was a week before Father’s Day. All but two of the songs had been written in an unexpected rush of expression that started at Valentine’s Day. He specifically references those poignant holidays when giving the timeline.

As he plucked that first note for “Famine Walk” (one of two songs on the album written during a two-month writing residency at a small art college on the west coast of Ireland, before the cancer diagnosis), he had no idea it would be how he opened the album. He had no idea he was making an album.

He just wanted to get these songs down while they seemed fresh, and that’s all he thought he was doing in the course of two quick days of recording with his son, as well as reeds player Levon Henry, pianist Patrick Warren and guitarist John Smith sitting in on some of the songs, and with David Piltch playing bass on “Book of Common Prayer.” At the end of the second day, he went home to listen to the recordings, sitting in his office with his wife Melanie Ciccone, Levon, and a friend. Only then did he really hear what he had.

“We just listened to the whole thing,” he says. “And it was so obvious to me and to everybody in the room listening back that it felt fully realized. I mean, it’s raw. It’s really spare. But emotionally speaking, I heard it and thought, ‘I don’t know if I’ll get closer to the intention of these songs.”

The only thing added later was the background vocals of Allison Russell and JT Nero, AKA Birds of Chicago, on the songs “In Time for Tomorrow” and “The Fact of Love.” He would have added his longtime drummer Jay Bellerose to some of this, but when he sent the tracks to him, Bellerose responded with a simple voicemail: “Um, not on your life.” His drummer’s instincts of when not to play, though extreme here, were exactly right.

In its sense of space, The Gospel According to Water is a perfect portrayal of the experiences that brought it about, mystifying and mystical in as personal a way as can be. At times it’s as elliptical and elastic as the engagingly playful folk-jazz that’s been a signature of his last several albums. But here that portrayal is stripped down to its essence.

At the center is the natural fragility of Henry’s voice as he lingers over key words and phrases in ways that can be enchanting and startling, sometimes both at once. While it’s instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with his work, it stands apart not only from his previous 14 solo albums, but also from his many production credits: for New Orleans titan Allen Toussaint’s final works (including the 2006 The River in Reverse, a collaboration with Elvis Costello following the city’s devastating flood), Bonnie Raitt, Rosanne Cash, Bettye LaVette, the Milk Carton Kids, Joan Baez’s most recent album Whistle Down the Wind, and Rhiannon Giddens’ and Francesco Turrisi’s stunning there is no Other.

But he winces at this being considered his “cancer album.” He even considered trying to avoid the topic in interviews and promotion of the release. But ultimately he opted for openness.

“Whether it’s fair or not, it’s going to happen,” he says. “I lost a little bit of sleep over that, wondering how I can mitigate that. And then I just realized that I can’t now, more than I ever could, control how people respond to the music — if they respond at all — and rein that in… People are going to hear it like that, and there’s not much I can do about it. It’s an aspect of how this record happened and what it is.”

Indeed, as the music made its way out to the world, friends and fans alike started sending him notes, almost all mentioning his health issues. He came to accept that for the good intentions, too.

“I just believe in the songs enough,” he says. “They’re already moving out into the world without me. They’re going to have to make their own way. They’re going to have to straighten their own teeth, find their own job. I can only do so much and when I go out and perform these songs, I may or may not at times offer any framing context about how the songs occurred or when they occurred.”

He references a comment made many years ago by his mentor T Bone Burnett, who produced Henry’s 1990 album Shuffletown, when discussing his Christian faith in regards to his art. Burnett said that while some sing about the light, he sings about what he sees illuminated by the light. Henry addressed that, in his own way, when he first played a few of the songs in public, in a concert at the Los Angeles’s Largo theater.

“Part of my preamble was to say, ‘Look, I know I’m holding this shoehorn that would help you into the tight fit of a big batch of new songs. And if I have one reluctance to hand this shoehorn over it’s because I don’t want you to think, from what I’m about to say, that where a song comes from is what a song is,’” he says. “A song is not where it comes from. Just because my particular health crisis has invited me to receive these songs in a particular sort of way, that is not what the songs are.”

He thinks back to being with Toussaint, doing interviews right after New Orleans was flooded in 2005, his home among the many destroyed. In interview after interview, Henry saw Toussaint refuse to deliver the “heartbreak” stories journalists craved. Finally, when pushed by a CNN interviewer, he made his point.

“He said, ‘You have to understand something: More than a drowning, this was a baptism,’” Henry recalls. “And talk about something that silenced the room, myself included. I’ve thought about this so many times since this occurrence for me, the fact that Allen wasn’t in denial about what had just happened. He just had the ability to see, that his vision didn’t stop with this trauma. He was seeing beyond.”

Some of that is elusive on the album, found in shadows cast by the metaphorical light. The song “Orson Welles” is a good example, with its arresting chorus: “You provide the terms of my surrender, I’ll provide the war.” He’s still mystified how that one came about, the words written as he and Melanie flew from Burbank to San Francisco.

“That’s just something I found falling off my hand,” he says. “I open my notebook and I literally watched my hand write ‘Orson Welles’ at the top of the page. And I didn’t know what Orson had to do with anything. It’s just one of those moments where it felt spring-loaded. I didn’t believe I was writing about Orson, but I believe that somehow his specter was kind of directing, gesturing me on to something, somewhere I needed to go in that moment. And I just followed, because, you know, who wouldn’t?”

He found himself thinking about a part of Citizen Kane in which Welles’ title character wants his newspaper to have headlines from a conflict in South America that is petering out, so he cables his correspondent there, “You provide the prose poems, I’ll provide the war.” (In real life, William Randolph Hearst instructed his staff, “You furnish the pictures, I’ll provide the war.”)

For Henry it took a different turn, though, with the idea of surrender — certainly tied to his health situation, and the ultimate lack of power over it, but extending far beyond that.

“I feel like I’ve written about surrender a good bit,” he says. “And I don’t mean surrender in terms of resignation, I kind of mean surrender in terms of radical acceptance, which is empowering, which is motivating, as opposed to the idea of collapse.”

Two titles stand out, though, for the clear view of the basics of life, the perspective brought by such things as loss, age, kids growing up and facing mortality. “The Fact of Love” is pretty much self-explanatory, but “Salt and Sugar” really captures it. “Everything is salt and sugar now,” he sings, boiling it down to things that make life possible and meaningful — though too much of either can kill you.

He explains that he and Melanie have been doing some “decluttering” in recent years, having left the large house in which they raised their two kids, and moving twice to subsequently smaller places. But the song definitely shows what he’s seen from the light brought by his health.

“It’s paring things down to salt and sugar,” he says. “Everything. What matters? How do you make a record? How do you express what you want to say? Who do you spend your time with? What do you spend your days doing? All that.”

He recounts many of the changes in his life in recent years, the moves, the attachments and the letting go of attachments. Finally, he sums it up in a way that gets to the heart of what he has done with The Gospel According to Water, and it’s just as on-point as that note he plucked to start the album.

“I mean, just, you know, occupy life.”

Photo Credit: Jacob Blickenstaff