Although her voice is instantly identifiable to even a casual country listener, Tanya Tucker has perpetually reinvented herself in the public eye since she debuted with “Delta Dawn” in 1972. From a mature teen singer in the ’70s, a scandalous star of the ’80s, and an award-winning vocalist in the ’90s, it’s never been easy to define her.

Now she’s back with While I’m Livin’, a stunning song cycle that shows her tender side as well as her rowdy, ready-to-party personality. It’s her first album of new material in 17 years, and by working with producers Brandi Carlile and Shooter Jennings, she’s made the most striking album of her career. Here’s the first of our two-part interview with Artist of the Month, Tanya Tucker.

BGS: I’m sure you’ve been approached to make a record over the last 17 years. What was it about this situation that made you say, “Yeah, let’s do it”?

Tucker: I’ve been working on other projects that I’m doing on my own. I’m really proud of those things and I hope that they see [a release]. I feel like this album, for some reason, is going to open that door. It seemed like before it was low interest. I don’t feel like there was a lot of interest. Maybe there was, I didn’t know about it, but when Shooter said something to me about it, I was like, “Yeah, great, great…” I went off and did Tucson and forgot all about it.

But I came back and it snowballed, and before I knew it, I was in LA doing some recordings on songs that I really didn’t know. I do my deal. I’ve done it all my life. When a song is pitched to me, I put my own something on it — I’ve changed a lot of ‘his’ to ‘her’ and made it my own. That’s one of the biggest compliments I’ve gotten from songwriters. I’ve heard from many of them that I can take their song and make it my own. They’ve always told me that, so it’s a very big compliment to me and I think that’s important. But this kind of came out of nowhere. I really can’t explain it. It kind of just happened and I don’t know how it happened. It did though. I’m pretty sure.

I’ve heard it, it’s real.

I think it is real. I’ve listened to it a few times and the good news is that the more I listen, the more I like it. Because it started out not that way.

What was your first impression of the final product?

I said, “No! Absolutely not.” I just didn’t hear it. I didn’t hear the songs as being anything I could really get into, or put my heart into. I really didn’t think it was going to be that good. I was wrong, and I love being wrong. I mean, I’m wrong a lot, but I was really wrong about that.

What was the relationship like in the studio with Shooter, and what’s he like as a person?

Well, Shooter’s great. I’ve known him before he was Shooter. But if you really would concentrate the time we spent together — very little time. But we spent more time probably on this project than we ever had, and we’ve become best friends. I wouldn’t say I had any better friends. He’s as good as any friend I’ve got.

Good. How about Brandi?

Oh, Brandi. She’s not even right. She is not local. She’s not of this world, she’s just in it. Yeah, she’s very exceptional. Something about her communication skills — maybe it’s just me, I don’t know, but I’ve watched her with everybody and you see the respect people have for her. … That’s the way that you want it to be. The way we made that record — I wish they were all that way. Brandi’s the same way [as Shooter]. I feel like she’s my best friend, totally. And I’d never heard her sing. Not until the Grammys and we were already done with the album.

What did you think when you heard “The Joke”?

I was blown away. Yeah. Blown away. And I loved “That Wasn’t Me.” I think I’m going to learn that one. I may not record it but behind closed doors I may learn that song. If anything, to just say thanks. Hell, she knows all of mine, I should probably start learning a couple of hers, you know? I’m way behind.

Well, it’s important who you surround yourself with. I mean, I don’t have to tell you that.

It used to be really hard for me to see anything bad about anybody. My dad was real good at seeing it before they even knew they were. He was very good about that. I hope that I am acquiring his skills. I’m still not as good as he was.

About a week ago, I read Nickel Dreams [Tucker’s 1997 memoir] and he was like your co-star in that book.

Yeah, well, he is the star, as far as I’m concerned. I’ve never read the book, but they’re on to me about writing another book. I really think that’s the real story. If there was a movie, I believe it should be his life. And then when I get started, that would be the end of the movie. Sequel! I plan ahead. But I think his story is phenomenal and it really needs to be told. His life was pretty unbelievable.

Your childhood is pretty interesting, though, too. Living in Utah…

Arizona, Nevada, and Arkansas.

It is a very dramatic life.

Yes.

It would work well for a script.

Yeah, well, I lived it, so it’s not so interesting to me, but maybe it is. And if it is, then that’s great.

What do you think your dad would say about this record if he had a chance to listen to it?

Oh wow, that’s a good question. Wow, oh wow…. Well, I’d have to say I believe he would love it because there’s two or three songs in there about him. The Twins [Carlile’s longtime bandmates, Tim and Phil Hanseroth] and Brandi actually wrote and custom-fit those songs to me, which is a real talent right there. One that I do not have, among others. But they have the talent. I don’t know if they have it all the time or if it was just this one time. They brought it all together. I don’t know. But I know that it’s unusual.

In fact, Brandi said, “God, I’d give anything if I could’ve met your dad.” And I told her, “Well, he didn’t like many people, but I do believe he would’ve liked you. I really do.” … I think he would like those songs but I think he would definitely be proud of “Bring My Flowers Now”. Because he always told me — Oh my God! You know what? I just figured something out.

What’s that?

My dad told me once, he said, “Let me tell you something.” He said, “The biggest record you’ll ever have, it’ll be the one that you wrote.”

How old were you when he told you that?

Oh, he told me several times. I was already started. I mean, it wasn’t when I was a kid, but many times he’d tell me that. “That’s what you need to do, is write.” But he didn’t like the association that I had to associate with to write. Because back in the day, party party party. Stay up all night, write a few songs. Stay up for a few days and something’s going to come out of it. He didn’t like that part of it. Now it’s become like a business. Meet me at 8:30 and we’ll write until 10:00, we’ll be done before noon.

But you had the Song House, which I read about in your book. You lived there, and then all the songwriters would come over.

Yep, right. Yep, that’s true.

So you love that association.

Oh yeah. I love to party, too, so it all kind of went hand in hand, like alcohol and cigarettes, or cocaine and cigarettes, and alcohol. And blackjack, throw that in there.

Read the second part of the interview.

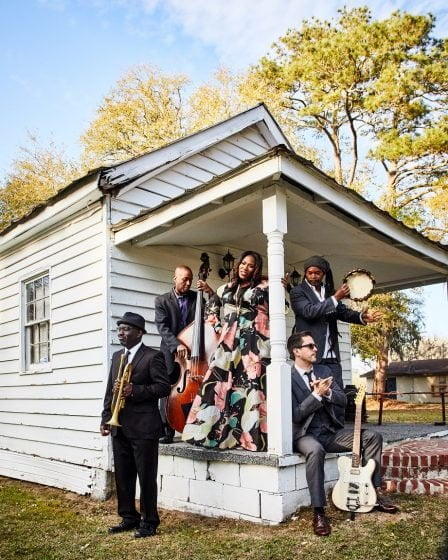

Lede photo: Derrek Kupish