(Editor’s Note: Sign up here to receive Good Country issues when they launch, direct to your email inbox via Substack.)

An often nameless, faceless character present in all country music is land. In a genre commonly referred to as country & western, land is a constant presence, whether foreground or background, evoked or painted, longed-for or spurned. Another nameless, faceless character that comes hand-in-hand with country and its relationship to land is colonialism – white supremacy, genocide, and imperialism advanced by music that claims to simply center nostalgia, rurality, and an “old fashioned” way of doing things.

This kind of revisionist history in country music – a sanitization of this nation’s past and present, in order to fit into widespread myths, around which this genre and our national identity is built – is no less pernicious simply because it is common and pervasive. It’s important to not only acknowledge country’s relationship with land, but to also attempt to deconstruct the ways that these roots genres perpetuate colonialist ideals and norms.

Can Good Country exist if it must deny the history of the land it professes to love? Can Good Country exist if it must deny that there would be no “country & western” without Indigenous people? These are questions that we feel are essential to ask, right out of the gate, even if their answers are not so simple. Good Country hopes to be a place that can represent all kinds of country music, but it cannot do that if we accept, uninterrogated and unexamined, that country’s relationship to the land must be good, moral, wholesome, and just.

At the heart of the second edition of

Counterpublic – an artistic activation described on its website as “a civic exhibition that weaves contemporary art into the life of St. Louis for three months every three years…” – just south of downtown and the towering Gateway Arch, sits Sugarloaf Mound. From April to July 2023, Counterpublic included twenty-five public art installations at a variety of locations, including Sugarloaf Mound, a sacred site for the Osage People and the last intact mound in the city. In earlier eras, the area was home to many thousands of Indigenous people – and the largest city in what would become the United States,

Cahokia.

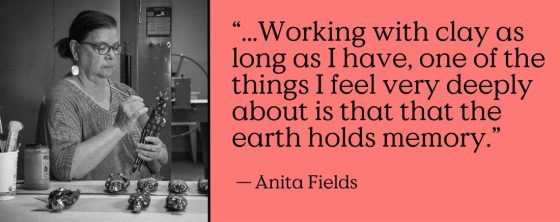

Adjacent to Sugarloaf Mound was the first Counterpublic installation and site, a collaborative piece that wove together sculpture, land, and music by mother-and-son artistic duo, Anita and Nokosee Fields. Anita Fields (Osage/Muscogee) is a fine artist who works in many media, but especially clay and textiles. Nokosee Fields (Osage/Cherokee/Muscogee) is a critically-acclaimed and in-demand old-time fiddler, equally at home in country and Americana as in old-time and string band traditions, and with a great deal of expertise on Indigenous fiddlers and Indigenous fiddling.

Their piece,

WayBack, which was curated by

Risa Puleo, is synopsized as such:

“Created in collaboration with her son Nokosee Fields (Osage/Cherokee/Muscogee), Anita Fields’s (Osage/Muscogee) WayBack invites visitors to gather in physical relation to each other, to Sugarloaf Mound, and to Osage ancestors, history, and legacy. When the Osage Nation purchased part of Sugarloaf Mound in 2007, the sacred site was reabsorbed into the Nation through the auspices of property, extending Osage territory from the site of their displacement in Oklahoma back to their ancestral homeland. Atop this site, forty platforms are installed, modeled after those found at Osage events in Oklahoma. Each platform is embellished with ribbons that reference Osage cosmologies of balance between sky, water, and earth. Nokosee Fields’s composition for wind instruments invites further consideration of the earth from which the mound was constructed, the sky that unfolds above the platforms, the sound of the Mississippi River on the banks below the quarry and the wind that flows through the surrounding trees that transform first into breath. After the exhibition, the platforms will travel from St. Louis to Tulsa where they will be distributed to Osage community members completing the link between the current home of the Osage Nation and its ancestral homelands.”

“Middle Waters,” the labyrinthine composition by Nokosee that acted as soundtrack for the installation, its platforms, and the adjacent mound (listen via the Counterpublic site here), perfectly illustrates how adept country music – and its textures, styles, and traditions – can be at capturing the ineffable, spiritual qualities of land and our relationships with it. Fiddle, field recordings, wind instruments, voices, and more intermingle in a piece that feels as organic and grounded as Anita’s sculptures.

Now, after the installation’s closing, each of the forty platforms constructed by Anita and displayed at the Counterpublic site will be moved to what’s now called Oklahoma, to be distributed to members of the Osage community and to have a continued life, further illustrating how art, music, and land gain all of their meaning from the communities that interact with and rely on them.

On the occasion of Good Country’s inaugural issue, we spoke to Anita & Nokosee Fields about WayBack, “Middle Waters,” the Counterpublic exhibition, and how humans, land, music, and art intersect and combine.

Could you just take me into the inspiration and the conception of WayBack and how you started working together and collaborating on the piece, not only with each other, but also with the land and with the site? Um, maybe Anita, do you want to start?

Anita Fields: Sure. Over two years ago now I was contacted by Risa Puelo, who was one of the curators chosen for the Counterpublic triennial in St. Louis. [Risa] asked if I would like to join and explained their purpose, what they were doing, and what their groundwork was for the triennial. She said, “I know your whole family are artists, so if you would like to invite somebody from your family to participate with you, that would be absolutely fine.”

But let’s begin with what their goal was, and that was to talk about the difficult histories of a place. St. Louis is certainly one of those. The reason that I was asked to join was that, for the Osage People, St. Louis, Missouri – and even further than that – is our ancestral homeland. It’s a large area, including St. Louis, Missouri, Arkansas, and even further than that in the beginning, migration from almost the East Coast to the Ohio Valley, to where our written and documented history begins in Missouri. So that was our homeland and there are documented villages there, still, and lots of history there, because after Lewis and Clark’s expedition we held the trade there. After Lewis and Clark, we started interacting real heavily and marrying with the French, partially because the French were trying to hold onto political power through the fur trade.

That is our history there [in St. Louis]. And then of course came displacement. A series of treaties started moving us out of that area, ‘til we came into Kansas. We had a reservation there and then we sold that reservation and with that money we bought what is our reservation today from the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. That’s it in a nutshell, and of course it’s way more complicated than that.

Nokosee and I don’t live in close proximity to one another, so I was like, “Oh my gosh, is this going to be able to work over the phone and Zoom? That’s going to be kind of difficult!” Then an opportunity arrived for me to go to Bogliasco, Italy for a month-long residency. I asked if I could bring a collaborator, and that’s where we landed for a month – on the Mediterranean, in this beautiful, beautiful, beautiful place, on the coast of Italy, not very far from Genoa. We schemed and dreamed and planned. And it was very difficult trying to arrive at a place where we were both happy.

Nokosee, I wonder how, as a songwriter and composer, you began approaching this? How did you take your musical vision and dovetail it with the physical vision, with the sculpture, and with the place? What was the process like as you sat down in Italy to start creating together?

Nokosee, I wonder how, as a songwriter and composer, you began approaching this? How did you take your musical vision and dovetail it with the physical vision, with the sculpture, and with the place? What was the process like as you sat down in Italy to start creating together?Nokosee Fields: When we were both in Italy, I had a little field recording kit that I had been using. I would just roam around the grounds recording things. There’s the ocean right there, there are all these really intense waves happening, a lot of sounds to be had. There was also a poet, Robin Robertson, who was a fellow there at the foundation and I asked if he wanted to do any collaborating, because we had a lot of time there – it was a testament to the importance of having space and time to have creative thoughts. Which, I feel it’s really rare. For a lot of artists, you have to hustle a lot. We were there for one month, I was getting very regular sleep, I was eating three nourishing meals a day, and getting some exercise. And again, it’s also in this beautiful location, and we were surrounded by really smart artists. It was just a very stimulating, nourishing, and calm environment. I was able to actually have some visions and clarity. And I was able to indulge a lot of things – where, you know, most of the time I’m just barely piecing things together to make money or to pay rent.

It began with [Robertson] reciting a poem, then I started layering him reciting this poem with the waves and different sounds from around the grounds, manipulating them. I like the idea of using really intricate, small, detailed, fine sounds – using a really sensitive mic – and then turning that into something else. Or, pitching it, layering it on top of people’s voices or singing, or maybe something a little more recognizable.

For me, the space and time to have all of that creative flow happening – it took what felt like a month of just space to finally get somewhere with something. It was eye opening, a testament to needing space and time, because we kinda flip-flopped back and forth on what we were gonna do. I wouldn’t say we were struggling, it was just that we were in this new place and jet lagged. Our project was not hands-on, because it was just all conceptual, so it was a little difficult to land on something.

I do want to talk about the site, because – obviously I’ve only seen the photos – there’s an interesting juxtaposition of this kind of dreamlike soundscape for the piece with “Middle Waters” and then the site itself feeling somewhat shoehorned into modernity. You have the river there you have the highway here and of course there’s a billboard incorporated into the piece, as well. Anita, can you talk about how you wanted to play around with that juxtaposition with this sacred site that now is somewhat entrapped by modernity and by settler culture?

AF: There’s always a backstory surrounding my work, and how I came to be. I was born on the reservation and spent a lot of time with my grandmother, who was full blood, and I’ve chosen to be very close to my culture, even as an adult. As much as I could, I did what my grandmother did for me for my children, to make sure they have a place there, [in my culture]. In my own work, as I became older and older, I would be inspired by things that come from our worldview, which is a very complex worldview, but it’s very beautiful.

We still have those values. As a modern person, those values are still in place – you know, where I’m from. You can witness them in how we interact with one another, a lot of times. I think that is a very beautiful thing to know that what my ancestors left for us you can still recognize. A lot of my work surrounds that kind of thought, that there is another way of looking at the world that is not just a tunnel vision of, “We’re all like this and we’re going to go to the mall forever.”

And that’s our worldview; it’s way deeper than that. Through art, that’s a beautiful place to be able to tap into those kinds of thoughts and values. So I wanted, because that is our original homeland and that is such an important site, I wanted to be able to bring in this sense that we’re reclaiming that space again, marking it as ours, and [saying] this is who we are. I want people to know this is who we are.

Those wooden platforms are actually found throughout [our culture]. I’ll describe it to you this way, because this is the way I write about it: They have been around for a very long time. My earliest memories of them are when I was a young person, a young girl going around with my grandmother, and I would see them outside of large Osage homes or outside of our dances.

At camps, people have family camps, and these platforms would be there and you’d see older people putting their blanket down and sitting on it and then maybe somebody giving them a glass of lemonade or a Coke. And then they’d light up a cigarette and they’d be just visiting and laughing away with a relative or a friend.

And it always looked very calming and peaceful to me. Those are the kind of memories too that I often tap into. But it’s also much deeper than that. What I was seeing there was, yes peaceful and calming, that was happening, but I was also witnessing survivors who had gone through a lot just for us to be able to be here. There are always these links.

What better place to be able to bring those [platforms], because that is the place that we had to survive from, to move from St. Louis. I’m always interested in giving people a glimpse into who we are. It’s not my job to talk about ceremony or rituals or any of that kind of thing. But I want people, again, with that thought in mind, I want people to know who we are and that there’s a different way of looking at the world and it comes from very complex, intelligent thinking and is based on observing nature and the cosmos. These values and these systems are still here for us today.

With the platforms, we started by going to Google Maps, downloading maps and images, and the site was kind of big, so it wasn’t working with one platform. And we just kept going, “Guys, that platform is gonna drown in that big space!” It’s beautiful to be able to work with a great curator because between our conversations with all of us we decided, if the money can be found, maybe we can have more – it began there. That is how those arrived and then we topped them with designs that are familiar to us as Osage People. We painted those on there, designs that are used in our ribbon work clothing – which comes directly out of our interaction with the French, when we started trading for ribbons and needles and threads and thimbles and that kind of thing. This kind of interaction with the French and our time there totally changed our culture forever.

…You know, with working with clay as long as I have, one of the things I feel very deeply about is that the earth holds memory. That has been revealed to me, just because of how clay is made over time. I’m certain it holds the memories of who was there, wherever in the world.

I mean, in Italy, a couple of times when we would travel to these places and then we would read about the history, I felt that there, too. No matter where you’re at there are always the similarities to what has happened in history – “the conqueror” and “the conquered” – these stories are all threaded together and similar. I couldn’t see WayBack without sound in any way, shape, or form. It just wouldn’t have the punch that I was looking for.

I did want to ask, where are we at in the lifespan of the piece? I know that the plan is to distribute the platforms to Osage community members back around Tulsa. I just wonder where you’re at in that process?

I did want to ask, where are we at in the lifespan of the piece? I know that the plan is to distribute the platforms to Osage community members back around Tulsa. I just wonder where you’re at in that process?AF: Yes, it was temporary and as soon as Counterpublic closed, I think it was within two weeks, they were picked up and shipped back to Tulsa to the [Tulsa Arts] Fellowship. The Fellowship is storing them for me. Then I got a call from the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City, which is I think in its second year. They have a beautiful courtyard plaza and they have built a mound-like area where you can witness the solstices. The curator was at the Counterpublic closing and she said, “I want to bring these to First Americans Museum, what’s the plan for these as soon as this is over?” Well they took half of them and then half of them stayed here, displayed at a place called Guthrie Green in Tulsa for about a week. Yesterday, the ones from First Americans Art Museum were delivered to the Osage Nation. I want to distribute them to the Osage community. In my mind I’m like, “What am I going to do with 40 platforms when they return? What’s going to happen with these and who owns them?” And actually that was [curator Risa Puleo’s] suggestion: Is there any way these could be returned to the Osage community?

People are excited about it, those that know about it. Not a whole lot of people know. I’m trying to keep it [quiet] ‘til I get it all figured out, but they’re excited about it. I’m excited about it, too, because that is another way to make art accessible. To bring it back to where you come from. Because those folks are totally my inspiration, and I say this at every turn, whenever I have the opportunity. You’re my inspiration. Your grandmother, my grandmother, every interaction I’ve seen throughout my life. This is my inspiration.

Nokosee, I wonder, do you see a similar way of bringing “Middle Waters” to the people? Do you see a lifespan for that piece beyond this installation? Or do you think it’s a moment in time and it’s onto the next work?

NF: Yeah, I think it’s just a moment in time. I might edit it, but I’m pretty pleased with it. If anything, it’s more of a reason to want to do more sound installations, sound art kind of things. I’ve been wanting to transition to that kind of work. As much as I’ve enjoyed touring – and I’ll probably do it for as long as I can – I find it to be pretty taxing. It’s tons of fun, but I think I need something that’s a little more cerebral, a little more isolated, a little more supported, and also a place for my voice and creativity. I feel like I’m kind of waking up from an obsession where I just got into traditional American music, traditional fiddle. Now that I’m steeped in that world and I feel like I’m really a part of it, I also feel like there’s a lot of it I just don’t really care for.

This sounds really uppity, but making traditional fiddle music feels kind of separate from [country], it’s just melody. I like the foundational aspects of music and the research and tone, things like that. And I like it because it’s not really tied to lyrics, it’s not putting on a type of personality, like lyrical content [does].

That, to me, is often just perpetuating settler mythology about old-time music. There are a lot of things that could be said about old-time music that are also problematic. Instrumental music is where I really jive and get into stuff, but I’ve also had to constantly interface and participate in lots of country music or lyrical music that has content that, to me, just feels like propaganda with really rudimentary, basic understandings of the land.

It feels like a type of erasure. It’s just kind of designed that way – maybe not maliciously – but it’s just so deeply woven into how things work in this country. …I find a lot of country music today, a lot of the younger, popular stuff, it feels like it’s about convincing white people that they’re white or something. There’s this pseudo-woke take on country music, which I think is fine, it’s just not radical enough for me or something. It’s like it’s just enough for people to kind of maybe get their outlaw fix.

It still doesn’t work for me and I still find it very rudimentary and actually not very confrontational or very deep, as far as what’s actually going on in the world or on this continent.

Sign up here to receive Good Country issues when they launch, direct to your email inbox via Substack.

Lead Image: Anita & Nokosee Fields via Counterpublic.

Image of Anita Fields: Courtesy of the Artist.

Headline text from Anna Tsouhlarakis, “The Native Guide Project: STL.” Billboard and digital signage. Curator: New Red Order. Counterpublic 2023, Sugarloaf Mound Site.