We’re back with another excellent edition of our weekly roundup of new music, fresh videos, and sneak previews of tracks to yet to come.

Bluegrass power couple Benson – Wayne Benson and Kristin Scott Benson – call on Zack Arnold of Rhonda Vincent & the Rage for their new single, “Bully of the Town,” which drops today. You may recognize the track, which is usually performed as an instrumental, but its unique chord progression shines with Arnold’s vocal as the somewhat unexpected cherry on top. Also in a bluegrass space – bluegrass saxophone, of course – Eddie Barbash continues his mini-series with us of classic bluegrass and old-time fiddle tunes rendered superlatively, as only he could, on sax. This time, we’re sharing his new performance video of “Tennessee Mountain Fox Chase,” shot at Larkspur Conservation in Westmoreland, Tennessee. We can’t get enough solo saxophone fiddle tunes!

From the bottom of the globe, progressive New Zealand string band You, Me, Everybody returns to the pages of BGS with a new music video. “The Rest of Us” is a contemplative, introspective song set to sparkling newgrass that’s about leadership, abandonment, and rising above – if you can. From country, our friend Brit Taylor also debuts a new music video this week for “All For Sale,” her most recent single that released just last month. The new video, which only features a short cameo by Taylor, a new momma, is a fun-fueled yard sale spurred by heartbreak and readiness for a blank, clean slate.

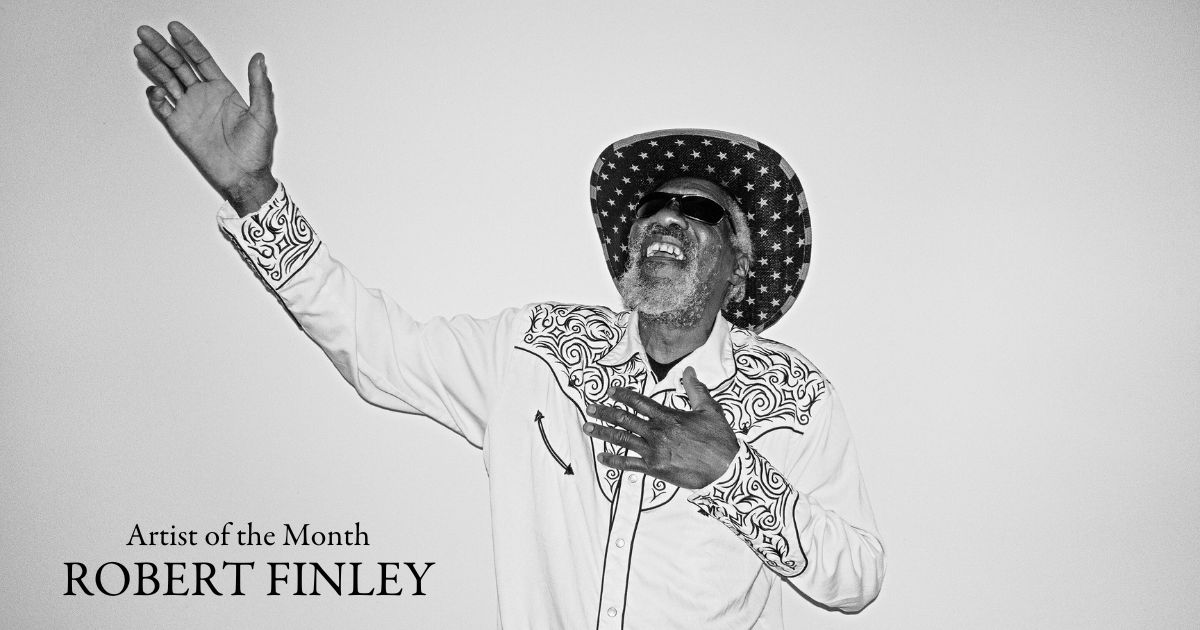

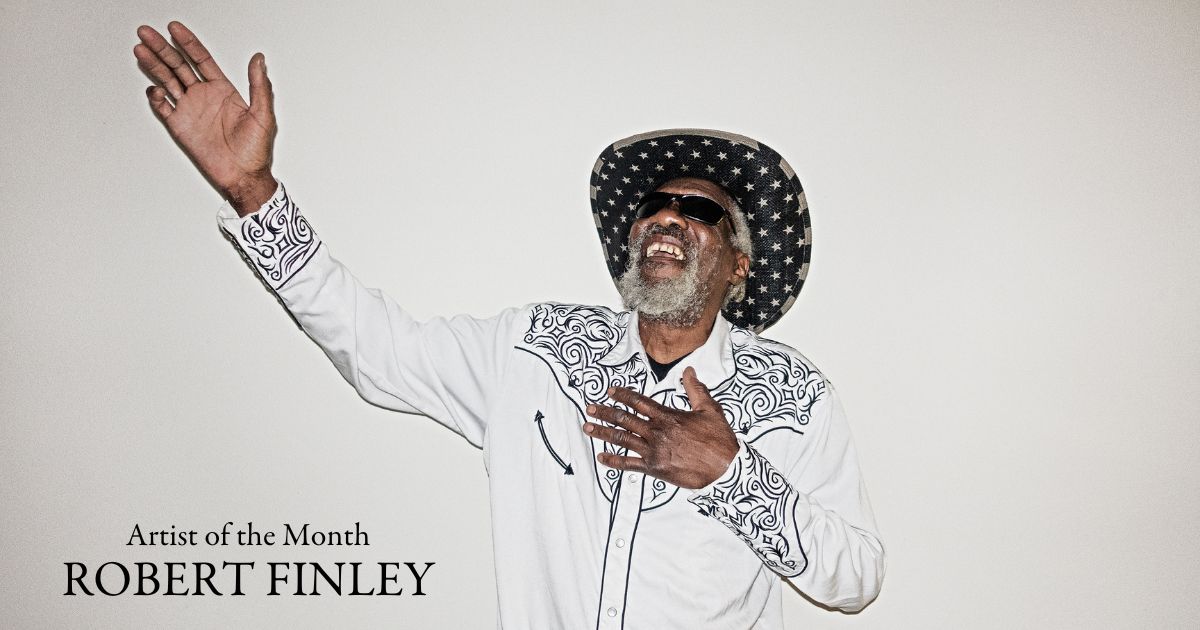

To round out our collection this week, legendary blues master Robert Finley is celebrating a brand new album via Easy Eye Sound today, so of course we’re highlighting a track from Hallelujah! Don’t Let the Devil Fool Ya to mark the special day. “Can’t Take My Joy” is an infectious song with a perennial message that Finley holds at the core of his values system – you really can’t steal his joy. And, with music like this in our weekly roundup, you won’t be taking our joy, either!

It’s all right here on BGS and, just like every week before this one, You Gotta Hear This.

Eddie Barbash, “Tennessee Mountain Fox Chase”

Artist: Eddie Barbash

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Tennessee Mountain Fox Chase”

Album: Larkspur

Release Date: November 28, 2025 (The album will be released one song at a time with the last track coming out Nov. 28.)

In Their Words: “This song was recorded during a spring sun shower on the porch swing at Larkspur Conservation’s cabin headquarters. A barn swallow was nesting in the rafters just over my head and I was inspired by all of the bird songs around me to improvise this introduction.

“I learned the tune late one night from Ric Robertson after a party/concert in his Washington Heights apartment in NYC. I believe he learned it from Nate Leath and my version is also inspired by his recording. I decided to slow it down a bit and give it a lazier, swingier feel that just feels so good to play on the saxophone.” – Eddie Barbash

Video Credits: Shot and edited by Jeremy Stanley.

(Editor’s Note: Watch the first video in our mini-series with Eddie Barbash here.)

Benson, “Bully of the Town”

Artist: Benson

Hometown: Boiling Springs, South Carolina

Song: “Bully of the Town”

Release Date: October 10, 2025

Label: Mountain Home Music Company

In Their Words: “I’ve always loved to play this song and didn’t even know it had lyrics for years. The chord progression is just different enough to make it work either way.” – Wayne Benson

“‘Bully of the Town’ is a good example of a song that wasn’t originally a part of the bluegrass genre, but is versatile enough that you can play it many different ways and it sounds like it belonged there all along. Wayne and I are pickers first and this arrangement is really built around being able to play around this fun chord progression, but the vocals are the icing on the cake, because prior to this cut, people typically played it as an instrumental. A lot of people don’t even know it has words, so adding vocals differentiates it and we got a young gun to sing it! Zack Arnold, from Rhonda Vincent & the Rage, did such a great job. He delivers it with a lot of energy, power, and a spirit that accompanies youthful musicianship. He really added excitement to an already-grooving track.” – Kristin Scott Benson

Track Credits:

Wayne Benson – Mandolin

Kristin Scott Benson – Banjo

Cody Kilby – Acoustic guitar

Kevin McKinnon – Bass

Zack Arnold – Lead Vocal

Robert Finley, “Can’t Take My Joy”

Artist: Robert Finley

Hometown: Bernice, Louisiana

Song: “Can’t Take My Joy”

Album: Hallelujah! Don’t Let the Devil Fool Ya

Release Date: October 10, 2025

Label: Easy Eye Sound

In Their Words: “There’s an old saying that I used to hear folks say, ‘There’s joy in the world, can’t take it away.’ Joy is something that can’t be measured by man and can’t be controlled by man. That’s why I say, ‘You can’t take my joy.’ You can take everything else, but you can’t take that. You can take my freedom and I can still be happy. Though there are problems, there is still a way to look beyond the faults and accept the good things in life. Joy is something that no man has the power to give and no man has the power to take away.” – Robert Finley

Brit Taylor, “All For Sale”

Artist: Brit Taylor

Hometown: Hindman, Kentucky

Song: “All For Sale”

Release Date: September 5, 2025 (song); October 9, 2025 (video)

Label: RidgeTone Records/Thirty Tigers

In Their Words: “We wrote this song like a script. There’s so much imagery in the song that it just seemed natural for the video to follow the lyrics. I decided only to make a quick cameo in the video and let my friends be the stars of the show! While it seems counterintuitive to what the rest of the industry is currently doing, it felt right to me. After all, the song isn’t about me, it’s about a story that wants to be told. And, honestly, my friends should probably move to Hollywood, because they really nailed their parts!” – Brit Taylor

Video Credits:

Robert Chavers – Producer, director, cinematographer

Steve Voss – Director

Solar Cabin – Production company

You, Me, Everybody, “The Rest Of Us”

Artist: You, Me, Everybody

Hometown: Ngāruawāhia, New Zealand

Song: “The Rest of Us”

Release Date: October 10, 2025

Label: Southern Sky Records

In Their Words: “I woke up with the melody and the lyric in the chorus, ‘If you’re the one who’s going to give up, what are the rest of us doing here tonight?’ And as much as the melody kept hooking me in, it took a while to find an angle for a song that could only really be about leadership. Even though it’s from the perspective of the people who are left when a leader abandons them, I was writing this with an awareness of how I felt I was letting people down at a time when I wasn’t following through on a commitment I had made. That’s why it’s less about blame and more about the heartbreak of watching someone lose faith in something they’d once worked so hard for.” – Kim Bonnington

Video Credits: Produced and edited by Kim Bonnington. Filmed by Ethan Bryant.

Photo Credit: Brit Taylor by Sammy Hearn; Benson by Sandlin Gaither.