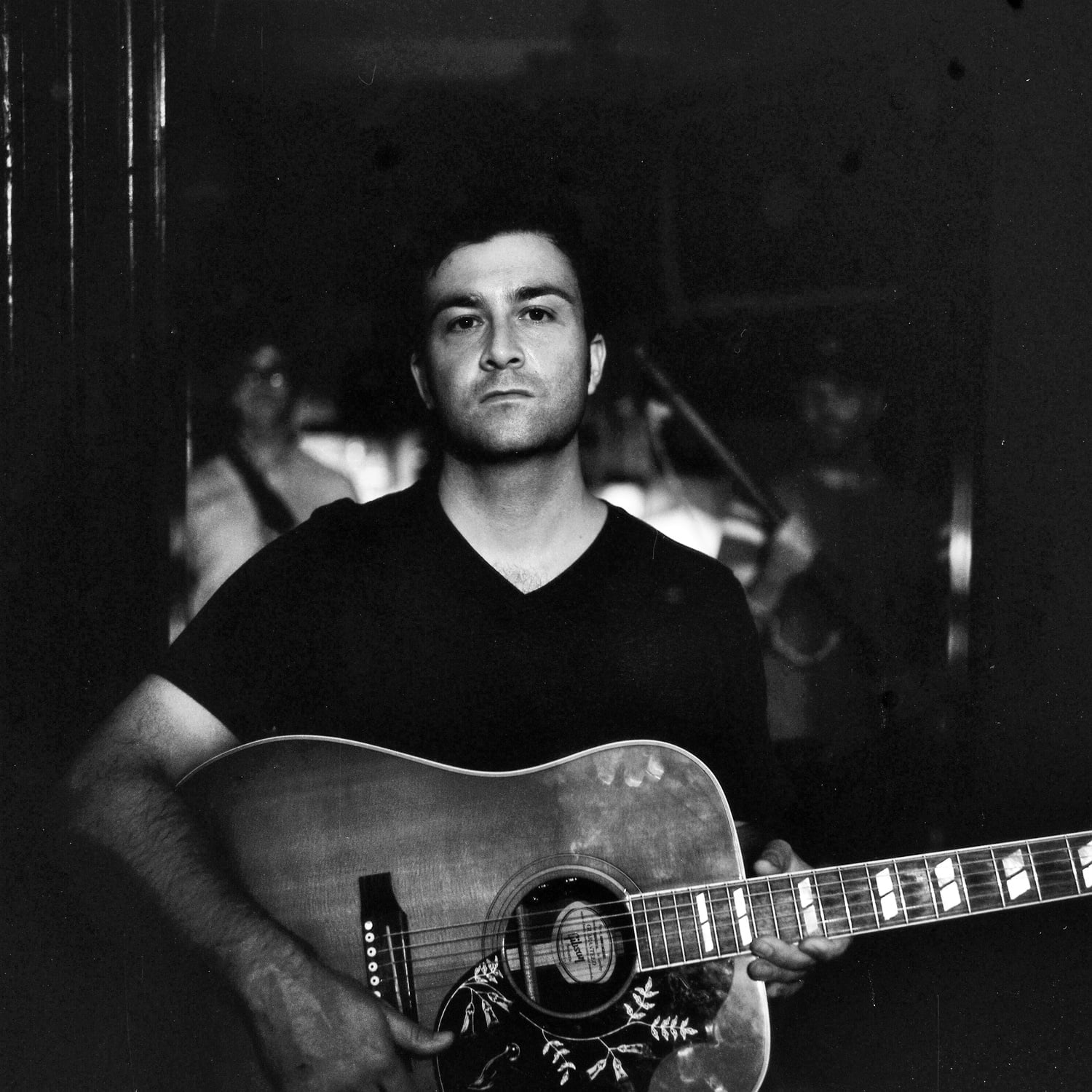

“I am here. I’m ready to play.”

That, Mickey Hart recalls, is the first thing Zakir Hussain said to him when the young Mumbai-born tabla player, having recently arrived in the U.S., knocked on the door at the Grateful Dead drummer’s Marin County ranch.

“Oh, okay,” Hart says he replied. “Here we go.”

That was 1970 and go they did, forming a deep musical and personal bond that lasted from that day until Hussain’s death from lung disease on Dec. 15 at just age 73. Hart had been studying with Hussain’s father Ustad Alla Rakha, Ravi Shankar’s long-time tabla partner.

“His father said, ‘I can’t play with you because I play the quietest instrument in the world and you play the loudest,’” Hart says, laughing in the den of his ranch house on a recent Zoom chat. “But he said, ‘My son, he could play with you. I will send him to you.’ And so he did.”

And? “It was just magic,” Hart says, beaming with the memories.

Soon Hussain moved into the barn studio facility at Hart’s ranch. And they played. And played.

“We played for four hours one time,” he says, then realizing that was nothing. “We played for four days and nights! Four days and nights! We really got to know each other and played every day. He was the crown prince of tabla, and when his father died he became the king.”

Father and son, in fact, duetted on Hart’s first solo album, Rolling Thunder, released in 1972. Soon other collaborations followed, including the creation of the Diga Rhythm Band, which grew around a multi-cultural percussion ensemble Hussain formed at the Ali Akbar College of Music in Berkeley. The group’s lone 1976 album also featured Hart’s Grateful Dead mate Jerry Garcia on two tracks.

“He loved Jerry, they just loved each other,” Hart says. “Their personalities were very similar. Jerry was really kind, loving, thoughtful, and so was Zakir.”

Hart and Hussain sparked creative energy in each other and an eagerness to explore.

“He taught me various ways rhythms could be used, exposed me to rhythms that I could never imagine, which I took to immediately, and I wanted to learn them,” Hart says. “When we did Diga Rhythm Band together, that was the first time I had to learn composition. He composed half of it and I composed the other half.”

If Hart had to learn new discipline, Hussain had to unlearn some.

“When he came to America he kind of picked up on some American traits, and he liked the looseness of my style,” Hart says, slipping back and forth between talking of Hussain in the present and past tenses with the freshness of this loss. “It freed him from the strictness of Indian classical music. My gig was a little serpentine, you know. His is straight down the pike. As accurate as he could be, it is like a machine. He’s the Einstein of rhythm, so playing with Einstein was really cool. But I didn’t have that sensibility. That’s not the way we did it in the Grateful Dead, right? And he loved that. He really took to it. And that’s what he said I taught him. It was a wonderful combination, a meeting of the minds and a meeting of the hearts.”

The meeting, and the mutual growth and openness to new vistas, continued as Hussain had key roles on Hart’s 1990 album At the Edge, 1991’s Planet Drum (which won the first-ever GRAMMY Award for World Music), 1996’s Mystery Box, 1998’s Supralingua and 2000’s Spirit Into Sound. Each brought together a world-circling community of percussionists on stage as well as in the studio.

With 2007’s Global Drum Project, the Planet Drum ensemble coalesced around a core of Hart, Hussain, Puerto Rican conguero Giovanni Hidalgo and Nigerian talking drum master Sikiru Adepoju, the quartet mounting several dazzling concert tours and coming together again for the 2022 album In the Groove. The joy they brought each other was clear to anyone who saw their shows.

The same spirit sparked much exploration throughout Hussain’s life. Around the same time he was creating Diga, he teamed in Shakti with jazz guitar boundary-breaker John McLaughlin, Indian violinist L. Shankar, and Indian percussionists Ramnad Raghavan and T.H. Vinayakram, rooted in traditional styles but reaching to new territories. Hussain and McLaughlin teamed regularly through the years with several other lineups (at times called Remember Shakti) and a triumphant final Shakti album and tour in 2023.

Hussain also had his own regular tours and recording projects with different ensembles under the name Masters of World Percussion, as well as a 2015 tour leading an East-West ensemble with veteran jazz bassist Dave Holland inspired by the oft-overlooked world of Indo-jazz.

Taking another tack, with Béla Fleck and Edgar Meyer he created a banjo-bass-tabla triple concerto, “The Melody of Rhythm,” crossing lines of progressive bluegrass and both Western and Indian classical as documented on a 2009 album with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The three came together again in 2023 for the album At This Moment, which also features Rakesh Chaurasia on the Indian bamboo flute, the bansuri.

Other collaborators, among many, included Yo-Yo Ma, Van Morrison, George Harrison (Hussain played on the 1973 album Living in a Material World), Bill Laswell, and even Earth, Wind & Fire. He also had a long association with saxophonist Charles Lloyd that produced several wonderful albums, including 2022’s Sacred Thread, a trio with guitarist Julian Lage. And, of course, he made countless concert appearances and recordings with the top artists of Indian classical music.

“No one has crossed more borders than him,” Hart says. “Yeah, I’ve crossed a few myself. Not like him. He’s gone beyond me or anybody else I’ve ever met or heard of. He took to the air and went to all these different places, interacted magnificently with all these different cultures. What an incredible ambassador of music.

“And he was very kind when he played with you. He never overplayed, which he could do in an instant. But he was so kind, such a great person that he reserved himself. He never tried to show you up, he was never in competition with me. He was harmonious and rhythmically blissful, in a way. I guess you could call this bliss, bring the bliss word into this.”

Can Hart hear Hussain in some of his own and the Dead’s music?

“Oh God, yes!” he says. “Think of all the Grateful Dead rhythms.”

He cites “Playing in the Band,” for which he wrote the music with Bob Weir, adapting a piece called “The Main Ten,” a version of which appeared on Rolling Thunder.

“That’s 10/4 rhythm,” he says. “Nobody played 10/4 then! And there was ‘Happiness Is Drumming,’ which became ‘Fire on the Mountain.’ That was one we did in Diga. And the 7/4 on ‘Terrapin Station,’ and a lot on Blues for Allah. That was what we were playing in Diga and Phil Lesh picked up on it and everybody picked up on that rhythm and that became ‘King Solomon’s Marbles.’ No one did that in rock ‘n’ roll.

“So Zakir influenced me in so many ways, subtle ways and obvious ways. He was a big influence on the Grateful Dead. And he loved the way Bill [Kreutzman] and I interacted. That became kind of a model for him in some ways because it made it, I don’t know how you’d say it, legal for him in a way. He said, ‘Oh! Now I can do this! This is okay!’ Because only two drummers could do something like that.”

With all that, where would Hart recommend someone wanting to get to know Hussain’s music start? At first he insists that he couldn’t possibly narrow it down.

“I’d rather not,” he says. “Anything he ever played on is a wonder.”

But he gives it a little thought, mentioning several of the cross-cultural albums they made together, before focusing on Venu, a very traditional session he recorded in 1974 featuring Hussain in duet with Indian classical bansuri flute player Harisprasad Chaurasia. This came about when George Harrison’s “Dark Horse” tour, which featured the Indian all-star ensemble Ravi Shankar & Family (including Hussain’s father) as well as Western musicians, did shows in the Bay Area. Harrison and Shankar arranged for a private concert to be held at the historic Stone House, a granite building in Fairfax.

“We brought a bunch of them back to Marin County,” Hart says. “I had just got a 16-track machine from Ampex, threw it in the back of my pickup with a bunch of hay and all that. We went there and did the first 16-track remote recording.”

The music on the album is gripping, two long pieces featuring the venerable Rag Akir Bhairav, a devotional melody meant for the early morning hours, unfolding with grace and power. The first part is largely Chaurasia solo, with Hussain coming in for the second half, the pairing at times delicately rippling, at others building to frenzies, always in perfect, empathic sync.

Hart also cites Sarangi, a second album which he and Hussain co-produced at the same event with Ustad Sultan Khan’s sinewy playing of the bowed instrument that gave the album its title, accompanied by tabla player Shri Rij Ram.

Legacy is a difficult thing to predict. But to Hart, Hussain’s artistic importance is found in the drive the two of them shared to experience all music and cultures and to bring them together.

“He brought together cultures that no one had ever dreamt of, from Egypt with me and [oud player] Hamza El Din, from Nigeria with [drummer] Babatunde Olatunji, with Airto from Brazil. We introduced into the Western world something filled with all these gems and wondrous rhythms. That’s something that will never be forgotten. And all the cultures he touched around the world for all these years. He made quite a difference. There is no place that he’s played that he is not revered.”

It’s talking on a personal level, though, that Hart becomes emotional, effusive, as he reaches back through time to that day Zakir Hussain came to play.

“We just fell in love with each other,” he says. “We really liked each other. He is such a kind man. I don’t know anybody who doesn’t like him. I can’t say that about anybody else, actually.”

He throws his head back and laughs.

“He’s singular in that respect. And it reflected in his music and the way he played with other people.”

Photo Credit: Jay Blakesburg