“Welcome to Hard Times,” the opening and title track from country crooner Charley Crockett’s eighth album is Crockett at his finest. He is pensive and pitch perfect, relevant and retro. “The dice are loaded, and everything’s fixed,” he sings. “Even a hobo would tell you this.”

It’s hard to tell if the 36-year-old Crockett is the hobo he references in that line, though it’s entirely plausible. As contemporaries cut their teeth at Belmont and Berklee, Crockett was busking on the streets of New Orleans and New York. While there, he learned how to entertain an audience in pursuit of a tip; perhaps more importantly, he learned the ways of this world, how we’ve all been ushered into a 24/7 casino where the house is telling lies and the gamblers are predestined to sin.

Welcome to Hard Times, comprised of 13 tracks of searing anguish set to slick, ’60s-style, country-western production, culminates with the particularly sorrowful “The Poplar Tree.” It’s a song that Crockett says has been received differently by different audiences, even as he — a man living somewhere between Black and white, privileged and not — feels that his message is obvious. “I have, many times, on this album cycle, said to press folks, ‘Yes, we’re all oppressed folks, but some folks just have it harder,’” he says. “And you have to recognize that.”

By phone, we talked to Crockett about his album, the role of artist as activist, and, of course, these very hard times.

Welcome to Hard Times sounds like you wrote it for this moment — in the midst of a pandemic, with widespread racial unrest — but you actually wrote it before everything went down. What inspired you?

You didn’t need this shit going on this year to know about these problems that we’re talking about. I don’t know how you could travel this world as an artist and not see it. I think that says everything about the nature of people. I recognize people are in different positions, but there are a lot of people who are in positions to not see what’s going on, and there are no consequences for them. Then there’s everybody else who’s forced to see it, who deals with it and suffers for it.

You’ve definitely been vocal in interviews and in your music. But even as you speak now, I get this sense that there’s a push and pull, or a toeing of some line that you’re subconsciously doing.

I’m trying to walk this line that is strange because I have been identified by a lot of my audiences as just a regular white man. Then there are a lot of people that look at me strangely as the complete opposite, as African-American. But I can’t speak for the Black community and I don’t really feel like I’m speaking on behalf of the white community either. I never saw myself as Black but I never liked my whiteness.

What does it mean when you say that you never liked your whiteness?

I dreamt of myself and viewed myself as not white from probably 5 years old. And then I look at myself now in videos and stuff, and I just… I feel like I look strange.

I guess what I’m saying to you is: My issues with my own identity tie to the kind of James Baldwin viewpoint that whiteness is just a metaphor for power, and that my identity as somebody who is uncomfortable in my whiteness says a lot about the relationship between Europeans in America and African-Americans and Natives. The romanticization of genocide is an unbelievable crime, but I think what is probably more savage and brutal is the assimilation through rape, through bondage, through [people like] my grandmother [who was mixed].

The easy thing for somebody to do is say, “Well, you can’t skip white responsibility for institutional and structural privilege.” I see that, so I’m not saying, “Hey, whiteness isn’t real, therefore nothing that’s happening to you is valid.” I’m saying you have to recognize that it’s happening, and then, if you truly wanna change it, at what point in the future do whites need to stop looking at whiteness as meaning anything? That’s the step that I feel is completely absent in the national conversation.

There are conversations happening though, right? And white people, at least some of them, appear to be really listening.

There’s a combination of white consciousness, and then there’s this other, fake, white virtue signaling. I just can’t stand some of that stuff ‘cause I see a lot of these people playing politics with their public image who are not doing anything in their life about shit. It’s whites signaling to other whites, and that’s what Martin Luther King was talking about at the end, you know? He really was. I think Malcolm X saw it at the end; I think James Baldwin, because he was so intellectual, was saying it to everyone, but he managed to get away with it because I think he seemed like he was mostly speaking within that kind of elite, intellectual world.

“Blackjack County Chain” is a song written in the ‘60s about a Black chain gang in Georgia that kills their supervising sheriff. Word on the street is that Red Lane, the writer, offered it to Charley Pride, but he passed on it because he didn’t want to stir up controversy. You covered it on Welcome to Hard Times, and it’s the only song on the album that you didn’t write. Why’d you decide to cut it?

I sung that song mostly ‘cause I listened to the words and identified with it. I feel like I’m dragging chains, you know? I just do. I always have. I think that that’s the other weird thing about America that is really hard to recognize, for a lot of us. It’s, like, no matter how much better a lot of these people have it, the insane thing that I’ve seen about America is, even among all these people in positions of power and privilege, they all view themselves as discriminated against and oppressed.

Your song “Poplar Tree” discusses lynching. Was there a concern about going too far when you wrote it?

I don’t know. I wasn’t thinking a whole lot about where that song was gonna go. It just went there.

Right, because you said this stuff dominates your mind.

It just does. And it’s who I am. I am in the public eye on some level and people got all kinds of crazy shit to say about that. And it is not lost on me that, for whatever reason, these people saying the crazy shit that they’re saying about me, they got nothing like that to say about these people that I’m getting compared to in the independent, Americana country scene. Even if I can sing ‘em under the table, they don’t criticize how they sound, but they criticize me up and down. And I’m not blaming them; I’m not mad at ‘em, I’m asking for it, in a way. I know that I’m asking for it, ‘cause I can just pack up and stop doing this shit.

Like, let’s talk about folk music. Let’s talk about blues, back in the day. When these guys were singing about their situation, it was all code. It had to be code because if it wasn’t, that might mean your life. So I’m stepping up and down to say this shit loudly, but I’m trying to build my audience to a place beyond where it is now. I’m just saying, I don’t exactly know who I’m speaking for, really, because of how completely outside of this society that I feel.

How did playing on the streets for so long shape you as an artist?

To me, that’s the best education I could’ve ever gotten in my life. It was unfortunate circumstances and difficult living that brought me there, but I would never wanna go another direction. It’s informed what I’ve done, and I learned about folk music, hip-hop, and everything else. I just absorbed it all on the street, and I made it into what it is now.

I have people in country who look at me like, “This guy’s an imposter! Look at this video of him on the subway train ten years ago! He’s wearing a beanie and tight pants; he’s not a real cowboy! He’s not country music!” And I’m like, who is more authentic than me? I never got a leg up in the business, period. I never opened up for anybody of note. I built my career out of the most unlikely of circumstances.

Do you think artists have a responsibility to speak up about social issues?

It’s like this: If your art isn’t saying shit, I don’t care about your political opinion. Like, if your art isn’t making an impact, your political opinion, to me, is little more than you trying to get ahead. And I mean that about white people; I mean that about everybody. If the art isn’t doing anything, then what’s the point?

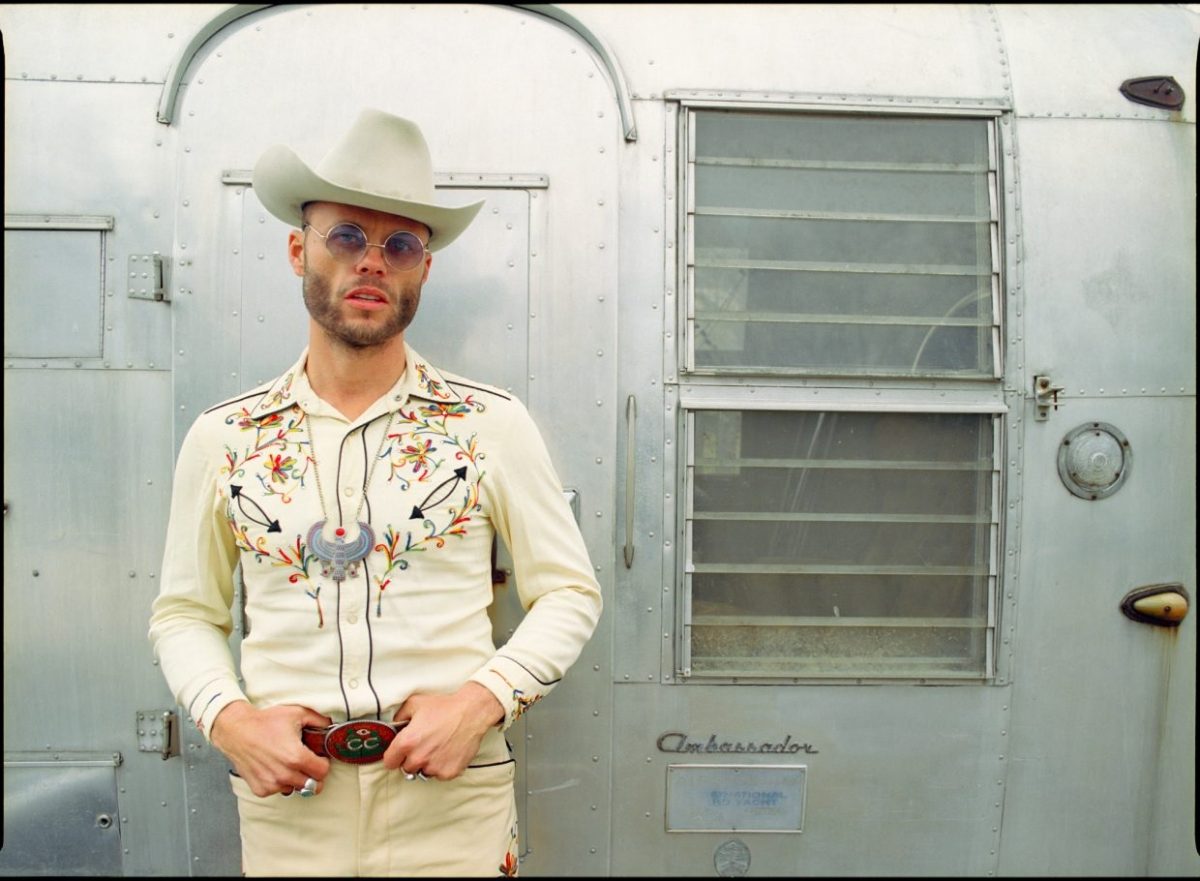

Photo credit: Laura E. Partain. See the full photo story.