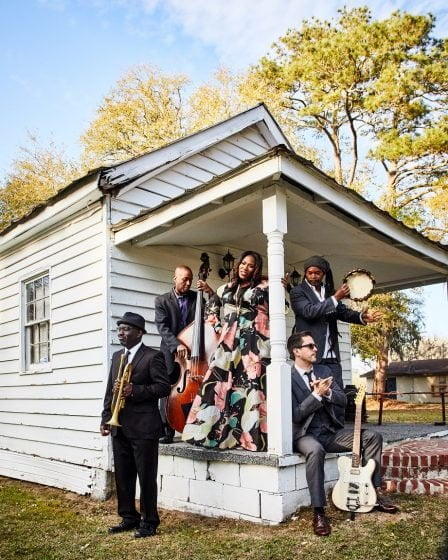

On October 3, 2020, during IBMA’s Virtual World of Bluegrass, I watched the Bluegrass Situation‘s presentation of Shout & Shine Online, the fifth annual showcase celebrating equity and inclusion in bluegrass and roots music. This year it featured Black performers, including Jerron “Blind Boy” Paxton, the blues, folk, bluegrass, and jazz multi-instrumentalist and vocalist from South Los Angeles. Not only do I enjoy his music, I also relish his asides and introductions. He knows a lot about musical sources, histories and meanings.

Introducing his music, Paxton explained that “ragtime” was the word people in his home community used to describe what others might call “old-time” or “traditional” — music that rekindled a shared past. At neighborhood and family social gatherings, he said, people would ask for his music by saying, “Play some of that ragtime music!”

For many people ragtime evokes the aural image of a piano played in the style of early 20th century composer Scott Joplin, an African American whose “Maple Leaf Rag” starred in the soundtrack of the 1973 hit film The Sting. (Paxton performed an arrangement of “Maple Leaf Rag” on five-string banjo for his Shout & Shine Online set.) The basic structure of this solo piano music involves the left hand keeping the rhythm often with large leaps in the bass register — often referred to as “stride” — while the right hand plays syncopated melody on the upper register.

In this form, ragtime is thought of as an urban phenomenon, straddling the border between popular and classical, and as the musical precursor of jazz. Joplin, for instance, composed an opera in 1911, and Julliard piano professor Joshua Rifkin’s 1971 LP of Joplin’s works earned a Grammy nomination. Pioneer jazz pianists like Jelly Roll Morton included ragtime in their repertoires.

Ragtime had another manifestation in the southeast, where Black musicians adapted it to the guitar in a fingerpicking style. Here, the right hand did all the work: the thumb picking the rhythm on the bass strings while the index and middle fingers ragged the tune on the higher strings.

The guitar was more affordable and portable than the piano. Ragtime guitar was featured by early 20th century itinerant musicians like Arnold Shultz in western Kentucky and Blind Boy Fuller in North Carolina. But it was not just the music of popular entertainment, it was also, as Paxton explained, social community music, performed for friends and neighbors.

In 1958 Peggy’s brother Mike Seeger produced Cotten’s first album for Folkways. “Freight Train,” already her best-known song, was on it:

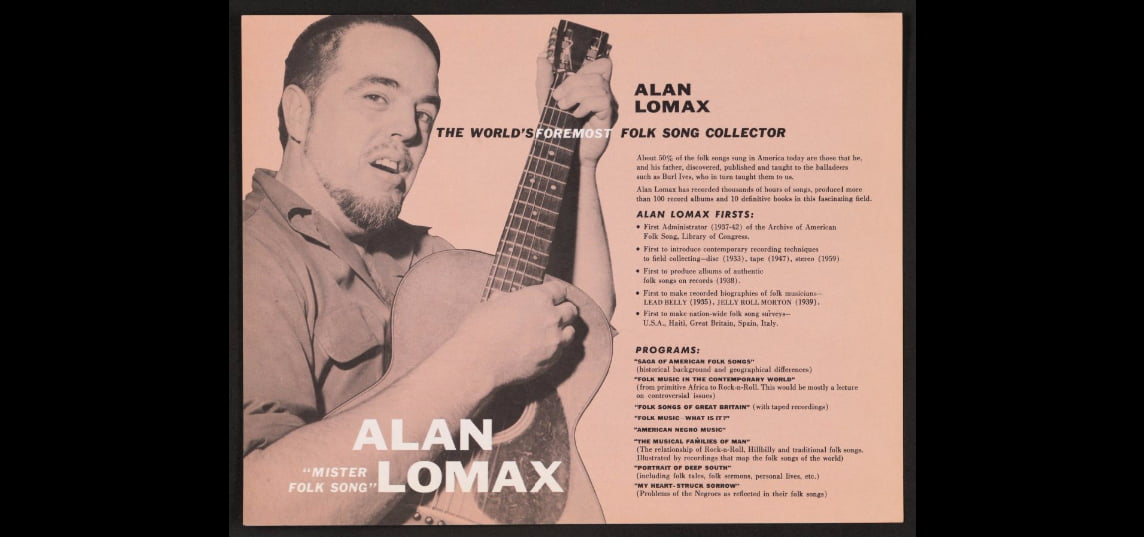

“Discovered” at the White Top (Virginia) folk festival in 1936, Smith and his sister, singer Texas Gladden, subsequently performed at the White House and were recorded for the Library of Congress by Alan Lomax in 1942. In 1946, Lomax introduced Hobart to New York record company owner Moses Asch. One of Asch’s new Disc label 78s launched Smith’s version of “Railroad Bill” into aural tradition among ’50s fingerpickers. Lomax recorded Smith again in 1959:

“Railroad Bill” was a well-known song in the southeast. Another song with a similar melody was “The Cannon Ball,” which Maybelle Carter of the famous Carter Family learned from Burnsville, North Carolina, native Lesley Riddle. In the late twenties and early thirties Riddle, an African American, accompanied A.P. Carter on song collecting trips and taught the family several songs they later recorded. Here’s a 1936 radio transcription of Maybelle singing and picking “The Cannon Ball”:

That changed in 1956, when a new version of “Railroad Bill” was released on an album, Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians. The first piece on the “B” side, it was fingerpicked by Mrs. Etta Baker:

This album was on the new folk music label Tradition. Based in New York, Tradition hit the ground running in 1956 with at least 14 albums representing Greenwich Village trends in the mid-’50s folk revival: lots of ballads, plenty of Irish and English singers, popular radio performers, folklore collectors, flamenco artists, new concert sensations, and two albums of field recordings in the style of Folkways — one from Ireland, and this one from Appalachia. The recordings for Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians were made by Tradition owner Diane Hamilton along with Liam Clancy and Paul Clayton in the summer of 1956.

Diane Hamilton was the pseudonym of Diane Guggenheim (1924–1991), an American mining heiress with a lifelong interest in traditional music, particularly Irish. At the time of the recording, Liam Clancy, soon to become part of the famous Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, had just arrived in New York, following an attachment with Hamilton. His brother Paddy was president of her new company.

New Englander Paul Clayton had studied folklore at the University of Virginia while pursuing a career as a folksinger. He recorded many albums from the mid-’50s until his troubled life ended in 1967 at the age of 36. Today he’s perhaps best known as a songwriter. His “Gotta Travel On” was a country hit in 1958, and his friend Bob Dylan borrowed from one of his songs to compose “Don’t Think Twice.” In 1956 Tradition had just released Paul’s album, Whaling and Sailing Songs from the Days of Moby Dick.

In his notes for Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians, Clayton described the album as “the result of a folk-song collecting trip during the Summer of 1956.” Hamilton and Clancy had recently arrived in New York from Ireland; Clancy was keen on collecting southern folk songs, and Clayton, who’d done a lot of that, was the obvious choice for expert guide.

The three met in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and headed west for a collecting trip to Appalachia. Their exact itinerary is unknown, but they went as far west as Beech Mountain, the highest point in the eastern U.S., well-known for its folk traditions. There they recorded folktale collector and performer Richard Chase doing three old-time dance tunes on the harmonica. In nearby Banner Elk, Mrs. Edd Presnell played three old-time tunes on her Appalachian dulcimer — an instrument then rarely heard on recordings that Clayton had studied and used in his performances.

The trio also visited Hobart Smith in his Saltville, Virginia, home, seventy miles north of Beech Mountain, recording four fiddle tunes and one banjo piece.

Their travel also took them to Blowing Rock, about a 25 mile drive from Beech Mountain, where they stopped in at the Moses H. Cone Mansion (also known as Flat Top Manor) a popular regional park on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Etta Baker, her father Boone Reid, and other family members were vacationing in the area, visiting the mansion. Reid, a musician himself, noticed Clayton was toting a guitar. He told Clayton of Baker’s musical talent and asked him to listen to Etta play her signature, “One Dime Blues.” According to Baker, “Paul was amazed. He got directions to our home and he was over the next day with his tape-recorder along with Liam Clancy and Diane Hamilton.”

They recorded five pieces. “Later,” says Clayton, “We met more of… a very talented family living in Morganton or Gamewell,” and they recorded two banjo pieces each by Boone Reid, then 79 years old, and Etta’s brother-in-law, her sister Cora Phillips’ husband Lacey.

Clayton’s notes indicate that they recorded “considerable instrumental material,” from which they chose “typical and best-performed” examples. This considerable material subsequently disappeared, leaving us today with only the album’s 20 tracks.

These include many familiar pieces from the local old-time repertoire. By following Harry Smith’s precedent in not identifying the color of performers’ skin, Clayton made the point that these musical traditions were regional, not racial. Perhaps since dulcimer player Mrs. Presnell’s first name was not given, all of the musicians were identified on the album notes as “Mr.” or “Mrs.” This lent an air of respect to the names of people often described elsewhere as “informants.”

Because of her fine guitar playing Mrs. Etta Baker was, for us, the most memorable performer on the album. A word of explanation — Mr. Hobart Smith was a fine fiddler, but in 1956 the fiddle hadn’t caught on in the folk revival. That wouldn’t start to happen until a few years later when the New Lost City Ramblers appeared.

With the exception of Smith, who led a string band for a while, the folks on this album made music as part of their social life, playing for their own enjoyment and that of family and friends. Sometimes they provided music for dancing — square dancing, and solo step dancing.

Here’s a good example of ragtime guitar used for solo step dancing: Earl Scruggs playing “Georgia Buck” live in 1961.

According to NCPedia, “buck dancing is a folk dance that originated among African Americans during the era of slavery. It was largely associated with the North Carolina Piedmont and, later, with the blues. The original buck dance, or ‘buck and wing,’ referred to a specific step performed by solo dancers, usually men; today the term encompasses a broad variety of improvisational dance steps.”

The Traditional Tune Archive describes “Georgia Buck” as “a black Southern banjo song,” so it’s interesting that Earl played it on the guitar in a style resembling that of Baker, Smith, Riddle and Carter. Where did he learn it that way? We don’t know, but Lester makes a point of describing his music as “hot” during the video and other musicians can be heard saying the same thing off-camera, seemingly endorsing the idea that this is good ragtime.

There are many stories of young white southern musicians learning from older black musicians in their hometown. One example: In 1972-73, Kenny Baker, then playing fiddle with Bill Monroe, did two albums with Buck Graves of guitar fingerpicking he’d learned from his brother, who’d taken lessons from “Earnest Johnson, a blind, black guitarist who sold peanuts in Jenkins, Kentucky during the thirties.” Rebel reissued them in 1989 as The Puritan Sessions (CD 1108).

Listening to Etta Baker on Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians was as close to taking lessons in that style of guitar as most of us undergrad folkies got. After the release of the album, she was not heard again on records for many years. Like Libba Cotten, Baker was a working woman with little time for making music. By the time she retired in 1973 from the Skyland Textile mill in Morganton, North Carolina, she’d endured family tragedies — the deaths of her husband and a son. After retirement she began accepting requests to perform and her music career developed. More about that next time…

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Neil V. Rosenberg: Terri Thomson Rosenberg