When Bettye LaVette sings “I Hold No Grudge,” she brings the weight of all her years to it. The 74-year-old vocalist draws out certain notes, delivers certain lines almost in a speaking voice, as though she wants to show us how difficult, but also how essential, it can be to let things go. “Deep inside me there ain’t no regrets,” she declares, “but a woman who’s been forgotten may forgive but never, never forget.” She draws out that second “never” to underscore its harsh finality, to remind you that she’ll live with the memory of this slighting forever.

“I Hold No Grudge” has never been merely a song about romantic betrayal — not when Nina Simone recorded it for her landmark 1967 album, High Priestess of Soul, and not when LaVette recorded it more than sixty years later. This new version sounds like it’s addressed to anyone who stood in LaVette’s way so many years ago, in particular those executives at Atlantic Records who saw fit to shelve her debut album in 1972 without so much as explanation, much less an apology. That decision crushed her and thwarted her promising career. “That’s exactly what it is,” says LaVette. “I probably have some grudges, but they aren’t big enough to make me stop. I’ve not been defeated. I’m extending the olive branch once again.”

“I Hold No Grudge” opens her latest album, Blackbirds, which collects her interpretations of songs made famous by Black women in the 1940s and 1950s, including Dinah Washington, Ruth Brown, Nancy Wilson, and Billie Holiday. She calls them “the bridge I came across on,” referring to that era between big band blues of the 1940s and rhythm & blues of the 1960s, when these artists were pushing popular music in new directions.

The most familiar tune on Blackbirds is likely “Strange Fruit,” popularized by Billie Holiday ninety years ago at Café Society in New York City and covered by countless singers ever since. As a result it’s difficult to make the song sound new and urgent, yet LaVette manages to do just that. Against her band’s dolefully trudging rhythm, she tilts the melody forward just slightly, as though pulling us toward some horrific destination, and she shreds the syllables of the song’s climactic declaration: “Here is a strange and bitter crop.”

That middle word is frayed almost beyond recognition – “stra-ya-ange” – to make the song’s metaphor sound tragically real. LaVette recorded it nearly a year ago and was startled when it became so heavily relevant again. To hear her sing “Strange Fruit” in 2020 is to be reminded that the injustices so many Americans are protesting — the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many other Black men and women — are not new or specific to the current era.

In the second installment of our Artist of the Month coverage, LaVette talks about growing up with a jukebox in her living room, giving these formative artists their due, and how Paul McCartney fits into all this.

(Editor’s note: Read part one of our Artist of the Month interview here.)

LaVette: People — especially white people — they throw “rhythm and blues” and “blues” together a lot. And now today, they’re throwing “rhythm and blues” toward young blacks and young whites who want to sound black. When people talk about rhythm and blues, they go back about as far as Etta James, but these women are the bridge that Etta came across on as well. Rhythm and blues was a music that came from blues, of course, and from gospel. When people ask me the difference between “blues” and “rhythm and blues,” I always tell them that you can cry to blues, but you can dance and cry to rhythm and blues.

It’s a short bridge, from about 1948 or ’49 to the burgeoning of Atlantic and Motown’s rhythm and blues, which was about ’61 or ’62. That’s when I came along. We took away the saxophones and added more guitars. We took the blues guitar and sped it up and put it in our tunes. The people who took us from the late ‘40s into the early ‘60s are rarely mentioned, and that’s why I chose this group of women.

I didn’t even know there were Black women who sang, other than Lena Horne and Dorothy Dandridge. And then, hearing LaVern Baker and Ruth Brown and Little Esther, I don’t know whether it gave me hope or whatever, but it really surprised me. I didn’t know that women who sung in such a bawdy way even existed.

When did you first hear these women?

When rhythm and blues came about, that was when I was young and I was dancing. That was when I was coming up and my sister was a teenager. We had a jukebox in our living room in Muskegon, Michigan, which is where I was born, and it had all the current tunes of the day, which my sister played daily when she got out of school. They were all rhythm and blues songs. You know, they weren’t into jazz — they were either blues or rhythm and blues songs on the jukebox. And gospel and country-western, no less. At one point, my favorite singers used to be Doris Day and Dale Evans.

Wait, you had a jukebox in your living room?

My parents sold corn liquor in the ‘40s and ‘50s. Muskegon was extremely segregated, so if you wanted a drink after dinner or after work, you had to come by my house. These were homes that had been built for the soldiers returning from the Second World War. So they were theoretically projects, but they hadn’t started making them out of brick yet. They looked more like barracks, and everybody’s house was just alike.

It was living room, dining room, small kitchen, two bedrooms, and a bathroom. My parents sold corn liquor and chicken sandwiches and barbeque sandwiches. There was no gambling. Nobody could cuss but my mother. But they could get shots and pints and half pints. And the jukebox was there in the living room where most people’s couch probably was. I was about 18 months old when I learned all the songs on the jukebox — all of them.

How did you choose the songs for this record?

I keep several files. Or, I should say, my husband keeps them for me. I’ve got all kinds of files. I’ve got a country and western file. I’ve got a strictly George Jones file. What I do is, I offer my label two or three ideas based on these files, and they tell me which one they like best. So I have some ideas that I like, and that way I don’t have to take their suggestions. If they find one they believe in and are willing to spend money on, I’ve got the songs already in.

I had this file here of standards, some of which I had done when I did little gigs in places around, just me and a keyboard player. Some of them, like Nancy Wilson’s “Save Your Love for Me,” I had done in other venues that most people haven’t seen me in, because they didn’t come where I was. A song like “I Hold No Grudge, which I heard eighteen years ago, it’s been in my file since then. I thought, if I ever get a chance to do that kind of album, I will do that tune. I wasn’t going to throw it away.

When did you discover that song?

I was living in Detroit, and I was getting my hair done. Usually in Black salons, there’s a radio on that plays Black music, and this song came on. I had never heard it before! And because Detroit is one of the places where I can pick up the phone and call whoever is playing whatever it is and I’ll know them, I called them up and she told me it was Nina Simone. And I said, well, if I ever get the chance, I’m gonna record that tune. That was eighteen years ago.

Just a few years ago I performed at a party for David Lynch, the movie producer, and this gentleman came up to me and said, “I loved your performance. My name is Angelo Badalamenti, and I do all the music for David Lynch’s films.” My husband, who loves David Lynch’s films, was ecstatic. Angelo says, “I have a tune. Years ago, I used to work with Nina Simone, and I wrote this tune for her that I think would be perfect for you.” I said, “What’s the name of it?” “‘I Hold No Grudge.’” I said, “I know you aren’t going to believe this, but I’ve had plans to do that tune for the last fifteen years!” So when I got the opportunity to do this album for Verve, I got in touch with Angelo and sent it to him, and he said he could hear Nina listening to it, closing her eyes, and saying, “Yeah, she got it.” Of course that made me feel very good.

Another song I wanted to ask you about is “Strange Fruit,” which seems sadly very timely right now.

But it just became timely! When we recorded it back in August, it was one of the oldest tunes on the album. And then all of this mess broke out, and the tune became timely! But all of this wasn’t going on when we recorded it. That’s not why we recorded it. We recorded it to fill in the Billie Holiday slot. While we were waiting for the album to come out, all of this happened. And it was just timely — as if we went to look for a tune to describe what’s going on now. So it’s bad that it’s timely — it’s awful that it’s timely — but it’s timely.

I knew the tune had not lost any of its power, and I knew I had to do it completely different from Billie. I’m blessed to work with Steve Jordan because he doesn’t hear these songs the way they were originally recorded. He hears them the way I sing them, because his age is closer to mine. He was born and raised in Harlem, and he grew up with these rhythm and blues tunes. He knew that I wanted “Strange Fruit” to be terse and sad and black and dark, and when we finished recording the music, I said, “Steve! I didn’t want it to sound exactly like they’re standing by the tree playing this song,” but it does. It’s just haunting. That’s the thing that makes Steve so important to me.

The outlier on the album is your interpretation of the Beatles’ “Blackbird.” What made that song fit this project?

The reason that I chose it — and I chose it for the title — is because many Americans don’t know that Brits call their women birds, and Paul is talking about a Black girl that he saw standing up on a picnic table singing one night in a park. He’s talking about a Black girl singing and I thought that that would just be perfect for it.

(Editor’s note: Read the first half of our Artist of the Month interview with Bettye LaVette.)

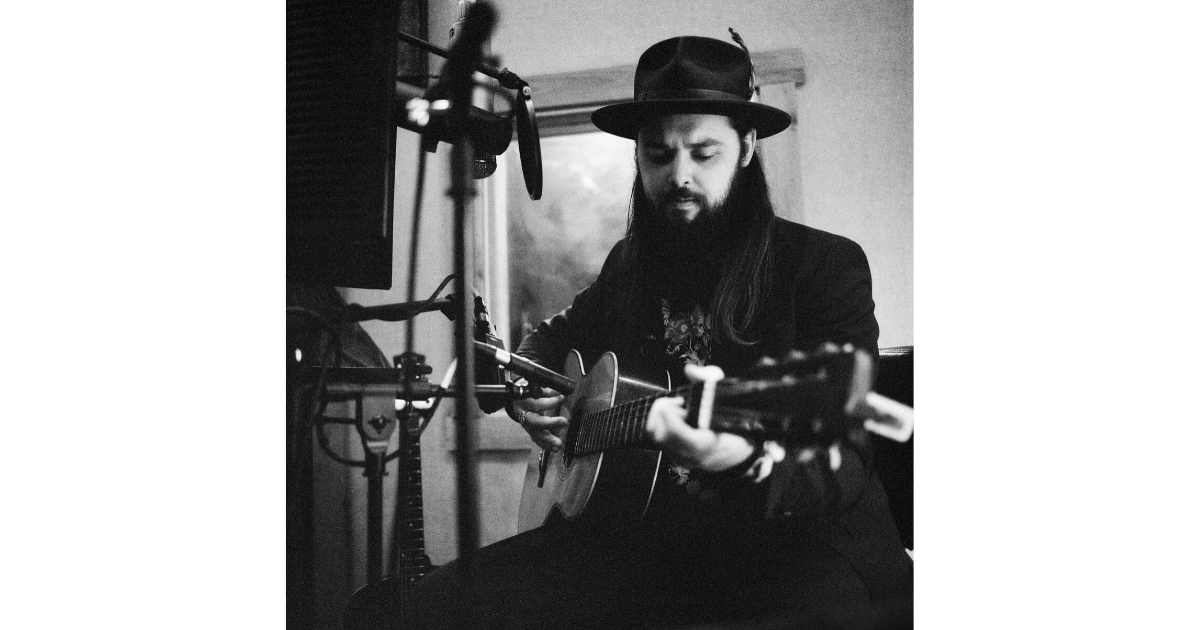

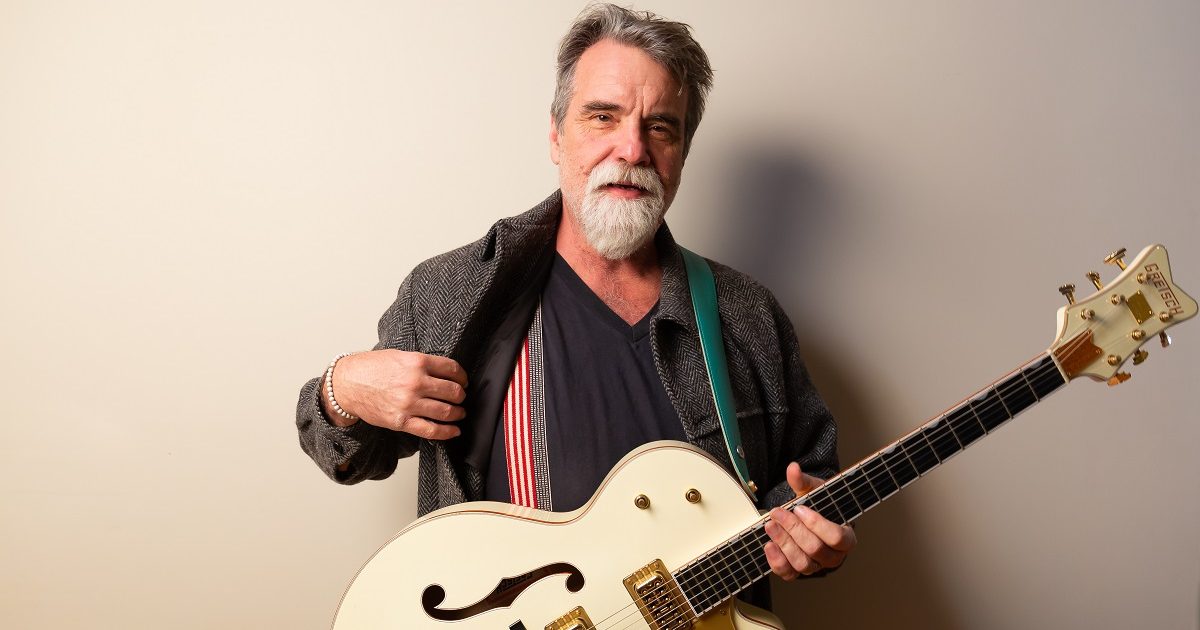

Photo credit: Joseph A. Rosen