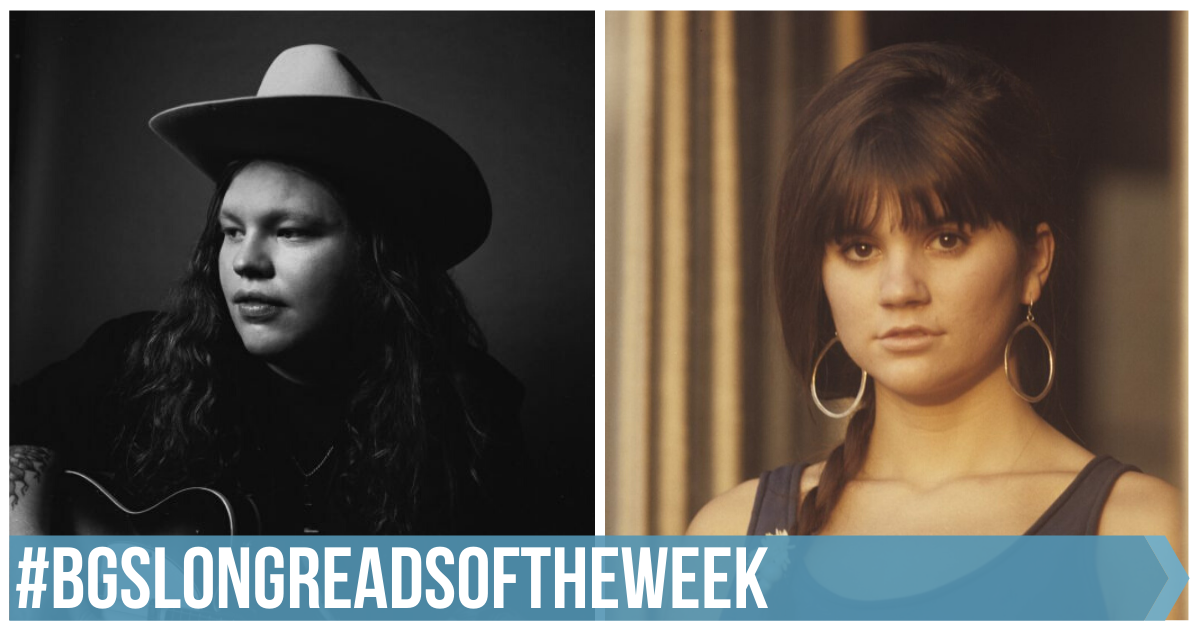

Laurie Lewis has lived most of her life in Berkeley, California, yet she’s primarily associated with music from Appalachia. A highly respected producer, she is admired equally for her singing, songwriting, fiddling and arranging, and her influences range from old-time and bluegrass to swing and jazz.

In 1986, Lewis released her first solo album, Restless Rambling Heart, which included seven original songs. Since then, she has recorded more than 20 albums with a variety of musical friends. She holds numerous honors from the International Bluegrass Music Association, as well as Grammy nominations for her own albums and collaborations.

Now nearly 35 years into her career, Lewis regularly pays tribute to female bluegrass pioneers, performs with and fosters a new generation of female musicians, and teaches at many of the nation’s most acclaimed music camps. BGS caught up with her by phone to discuss her new duet album, and Laurie Lewis, featuring old friends and new musical partners alike.

BGS: Why a duet album?

Lewis: It came about accidentally. I had an idea that I wanted to record a duet on (the Carter Family song) “You are My Flower.” Molly Tuttle and I got together to try it out and we had so much fun playing and singing that we went upstairs to my little studio. We turned on the microphones and just sang and played. It was so musically full, it didn’t need anything else. I thought, “Thank heavens, I have finally gotten around to singing this duet the way I’d wanted to for the last 20 or 30 years.” Then I got together with Tatiana Hargreaves. When we toured together, she and I worked up a tune I had written that she played on the fiddle, and I just loved that and I wanted to capture that. Then we got excited and did another song – and then I had three songs! I thought, “Maybe I’m making a duet album.”

Tom Rozum and I had worked out the Monroe Brothers’ version of “Will the Circle be Unbroken” for a Monroe tribute, and I just loved the way that sounded, and I thought we definitely should record that. It snowballed from there. I had lots of duet ideas where I thought a particular friend would be perfect on a particular song. So I went about collecting the versions of the songs. I recorded more things than are on the album. I have a few that are held back, just because I didn’t want it to be super-long and have people lose interest halfway through thinking they would never get to the end!

How did you decide to keep the instrumentation so spare – no more than two voices and two instruments?

After listening to what I recorded with Molly and Tati, I really liked what I heard. I fell in love with playing as a duet with Tom. We’re both essentially band musicians and used to having a whole band surrounding us, not just picking up the slack, but filling out the sound. When we started playing as a duo many years ago, it seemed really scary to both of us – and really empty. But we kept doing it, and I fell in love with the emptiness, that loose weave that you get with just two people and two instruments. And the way it becomes a conversation – my favorite way to have a conversation, just one on one.

How did you choose your partners and songs?

They’re all people who I have had long musical relationships or long friendships with. I’ve known Molly and Leah Wollenberg since they were babies. As the project went on, it felt as if these are some of my closest companions in life. These are the core people who have made a huge difference to my musical life in one way or the other

One of the last things I recorded for the album was “Old Friend” with Kathy Kallick. As the album started to take shape, I realized, “Oh my God, I have to have Kathy on here.” We have been singing partners and friends for more than 40 years. I just have to have her on here. But I couldn’t think of a song. The idea came to me as I was backpacking in the mountains: “‘Old Friend,’ of course!” It was recorded originally in 1989 and we’ve been friends much longer. It seemed like the perfect vehicle for us at this point.

Do you write specifically for an album, or do you just come up with songs, say, when you’re hiking, and then it shows up on an album?

Yes. I would say yes to both of those. For instance, I never expected “The Pika Song” [to end up] on the new album. I was just making up a little poem about pikas when I was hiking on the John Muir Trail. And then I was sitting around playing the banjo one day and I started singing it. When I mentioned it to Tatiana, she told me that some friend had just said that she thought the pika was [a perfect animal to match] Tati. She got really excited – she’d never seen one, but she got to hear all about them and play on the song and sing about them, so that was pretty fun.

Sometimes I will write things specifically for a group or for an album. I have lots of songs that I just don’t finish and sometimes the impetus of recording an album is what pushes me to commit to being done. So in that way I do write for albums. And sometimes just because the creative juices start flowing when you’re in a recording situation, a new song just comes along. And I’m grateful for that.

Did you choose songs that represented your own versatility?

Oh, no. I didn’t think about that. I really just thought about who was the right person to sing with on a particular song. Like the songs I did with Nina Gerber. There is nobody I would rather do certain songs with than Nina Gerber. “My Last Go Round” is a Rosalie Sorrels song. Nina worked closely with Rosalie and I got to play with her a few times. I recorded that song on a tribute album for Rosalie, and when we played the tribute concert, I played it for the first time with Nina. It felt so deep and healing. Music has a real way of being able to soothe and heal grief, and it really felt good to do it with her, and we’ve been doing it every time we play together since then. Nina’s electric guitar is the absolute perfect thing for “This is Our Home.” She fell right into it, just knew exactly what to play. She’s a mind reader.

Todd Phillips and I occasionally play “Baby, That Sure Would Go Good” in concert. We did it for years, but I never thought about recording it. When suddenly I was doing a duet album, I thought it would be perfect. And of course it was really fun. Todd’s bass playing is just out of this world. I mean that in every way you can think of. It’s crazy, but it’s great.

Tell us about “Troubled Times,” which is so appropriate right now. When you wrote it, were you thinking of something specific?

I wrote that about 20 years ago. I honestly cannot remember what inspired me to write it. It had some other verses, at least one other verse which I left out, because it wasn’t as good as the ones I used. I think it was politically motivated at the time, motivated to the outside world and my reaction to what was going on, but I can’t remember what specific event or events inspired it.

I had only performed with Leah Wollenberg once, at the Freight & Salvage, although I’ve known her all her life. One day I said to her, “Would you come over and sing one of my songs with me so I would have a recording of it”? I really didn’t know how it would go. So she came over and we recorded it. When I listened to it I said, “This is good! This is great!” So I asked her if she would be on the album. I think that I’ve just been sitting on that song waiting for the right combination of events, but also the right combination of voices to sing it with me.

Can you talk about the role of friendship in your music? You sustain such long-term friendships and musical partnerships. Is that unique to you?

I don’t think that’s unique to me. Musicians communicate very deeply through shared music. It’s impossible to play heartfelt music with other people without loving them, or at least learning to love them. And once you love somebody, you want to keep them in your life. So if there’s a problem, you work it out. You address it. You don’t let things go by and be on the surface. It’s what we do — we forge personal relationships that are strengthened through music, or are begun through music and continue past music.

Editor’s Note: Read part two of our Artist of the Month interview with Laurie Lewis.

Photo credit: Maria Camillo