Tag: Jerry Douglas

Jam in the Trees 2018 in Photographs

Black Mountain, North Carolina-based Pisgah Brewing hosted their third Jam in the Trees over the weekend of August 24 and 25, bringing together a harlequin lineup of Americana, alt-country, string bands, and bluegrass in the idyllic Blue Ridge Mountains. Whether you were on hand for every second of the musical magic or you couldn’t quite make it to the festival this year, relive the two day roots celebration with our photo recap.

Photos by Revival Photography: Jason and Heather Barr

WATCH: The Earls of Leicester, ‘Long Journey Home’

Artist: The Earls of Leicester

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Long Journey Home”

Album: The Earls of Leicester Live at The CMA Theater in The Country Music Hall of Fame

Release Date: Sept. 28

Label: Rounder Records

In Their Words: “In the bluegrass canon, the song ‘Long Journey Home’ has appeared under many alternate titles for different artists. Yet I’ve always felt Earl Scruggs’ banjo raised the Flatt and Scruggs version to a higher level. When planning our live record, we wanted to have a few fast tempo songs that we could count on to raise the blood pressure for both the listeners and our own. The tempo and fire that this song brings through Charlie Cushman’s banjo as well as Shawn Camp and Jeff White’s vocals made it an easy choice, and a welcome new entrant into the Earls repertoire.” – Jerry Douglas

Photo credit: Patrick Sheehan

Nefesh Mountain, “Eretz’s Reel”

For forty years now the Station Inn has lurked in Nashville’s Gulch, carrying the bluegrass banner in a town with pop country and cover bands to spare, while condo high-rises, wine bars, rooftop lounges, and organic groceries have sprouted up around the small, unassuming stone club. On any given night of those forty long years a bluegrass fan or a nonchalant passerby could step through the door and expect the best in bluegrass and old, real country. Luckily for every roots music fan in the universe, that fact is still true — and will be for the foreseeable future.

What one would not, perhaps, expect upon entering the Station Inn is vocals sung in Hebrew, or bluegrass songs based on Jewish traditions and turns of phrase. But on a recent evening, these were the sounds wafting from that fabled stage, as Nefesh Mountain performed songs from their new album, Beneath the Open Sky. It’s not as though bluegrass as a genre isn’t already predicated upon subverting expectations — it’s arguably a core precept of the form — but an average Station Inn patron might still be surprised by the Jewish-infused, modern ‘grass of Eric Lindberg, Doni Zasloff, et. al. “Eretz’s Reel,” an instrumental off the new record, is a less overt example of their Jewish perspective, but brings in a transatlantic flair, Tony Trischka-esque melodic turns, and a potent dose of originality and imagination. On the record, bluegrass phenoms Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas, and David Grier lend their talents to the track, but live at the Station, Lindberg stands apart as the imagineer and linchpin of this stripped-down version of the tune.

The Bluegrass Situation Expands: Meet BGS-UK

Think of the Union Chapel as London’s version of the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville.

An architectural wonder of a church, it still gathers a congregation for Sunday services. The rest of the week, however, it attracts worshippers of a different kind. The type who want to have a spiritual experience with Townes Van Zandt, Laura Marling, Father John Misty, The Civil Wars and Rosanne Cash.

In 2017, Sarah Jarosz sold out its 900 seats to a British fan base that knows her music well. “I don’t think I’ve ever sold out a venue as big as Union Chapel in the States,” she said at the time. “I’ve been blown away by the reception I get in England, Scotland and Ireland.” This year, she has already completed not one but two UK trips with Aoife O’Donovan and Sara Watkins, touring as I’m With Her. “I love coming here,” said O’Donovan. “We’ve made a home for ourselves here.” “You can actually see the growth,” added Jarosz.

This summer, the UK is awash with the diverse sounds of roots music. It’s as if everyone has suddenly woken up to the special relationship between the British folk scene and its American cousin. Major new festivals – like Black Deer in June, Maverick in July and The Long Road in September – are showcasing the powerful creative influence that Americana music is exerting on a new generation of British musicians: Jason Isbell and Passenger, Iron and Wine and Robert Vincent, Lee Ann Womack and The Shires.

Other fledgling festivals have begun bringing bluegrass and old-time to audiences that never knew they liked it before. In May, IBMA-award-winning Molly Tuttle wowed audiences at the Crossover Festival, which was started by a mother and daughter who wanted to hear and play the music they loved with their friends in Manchester. On the south coast of England, Beer and Bluegrass’s line-up includes The Hot Seats from Washington D.C., and Wesley Randolph Eader from Portland, Oregon, alongside some of the best bluegrass acts in Britain, including The Hot Rock Pilgrims and Midnight Skyracer.

Musicians who have toured the folk clubs of Britain and Ireland can attest to the strength of feeling that people there hold for the music of their native isles. And anyone who has encountered the Transatlantic Sessions, with Jerry Douglas and Aly Bain, has heard just how magical the bond that exists between the musical traditions of the old country and its American evolution. Celtic Connections in Glasgow has been fostering a creative exchange between artists on both sides of the Atlantic for decades, and the opportunities for future collaboration are limitless.

This July, Rhiannon Giddens will curate the Cambridge Folk Festival, an event which is always a highpoint of the summer calendar. Her program brings together women of colour from all over the US and the UK, including Amythyst Kiah, Kaia Kater and Yola Carter. “I love the UK folk scene,” Giddens says, “and I see audiences in the UK embracing the broad spectrum of what Americana really is even more so, sometimes, than in the US. A lot of people know the history of this music so well. I’ve always found a lot of acceptance here.”

So join our BGS-UK Facebook page, and join a community that’s excited to see where the music we love is going next. We’re excited about what’s happening across the pond right now and this is where you’ll be able to find out about all the gigs, artists, festivals and releases happening there. We’re ready for you, Britain!

Nefesh Mountain: From the Inside Out

In bluegrass, rags-to-riches stories are revered and glamorized, strong personal convictions are lauded, off-stage legends of wit and badassery are currency, and a sharp suit (rhinestones optional) and western hat speak volumes. There’s a notable correlation between the success of the genre’s greats and the presence of their personalities, perspectives, and stories throughout their art. The relatability, accessibility, and appeal of their songs can often be attributed not only to the level of talent, but also to the boldness with which their true selves are communicated, musically, to an audience. Roots music fans have always been hungry for indicators of an artist’s authenticity — a way to winnow out the performative, commercial aspects intrinsic to the recording industry and leave just the juiciest nuggets of “real life.”

Attempting to follow in that tradition and feed that hunger is Nefesh Mountain. Partners Eric Lindberg and Doni Zasloff want nothing more than to have the lens of their entire identities filtered through their brand of crisp, refined, and timeless bluegrass in myriad ways — tangible or intangible. Overtly, we hear this perspective in vocals sung in Hebrew, lyrical hooks derived from Jewish sayings, and a grassy cover of Irving Berlin’s “Russian Lullaby.” Deeper, more subliminally, we find that the themes of family bonds, a love for home, a respect for nature, and prayers for peace and empathy comforting our ears also stem from their Jewish background. But the specificity of this origin point is neither alienating or confusing. Rather, it reinforces two truths about this music: Bluegrass is for everyone, and bluegrass is indeed better when the people who make it shine brightly throughout it.

So many different folks from so many different backgrounds have analogous stories of how they come into roots music. What is it about bluegrass, old-time, and these more vernacular forms of roots music that allows the heart and soul of the music to effortlessly intertwine and weave itself into any background, experience, or personal story?

Eric Lindberg: That’s such a good question and something I think about all the time. I think that folk music — you could use “folk” or “roots music” — is synonymous with bluegrass nowadays. It’s all under that same umbrella. When I hear folk music from anywhere, it seems to be the music that translates in a spiritual sense or, for some people, a religious sense — which isn’t exactly where we’re coming from — or, as a general function of society, as a storytelling vehicle.

When I see and hear music from China, or Eastern Europe, or Australia, or Ireland, there’s kind of a pentatonic or maybe diatonic, very simple matrix of melody that has that high lonesome sound. There’s a certain thing about bluegrass that feels American to me; it connects me to our country. The way that the melody lilts connects me to the mountains, to the trees, and the things that I feel are undeniably true in the world. It speaks to my soul, as a human being.

As we’ve played our music infused with our Jewish background through the years, Doni and I have gotten in touch with our own hearts and our own worlds, breaking down the barriers between anybody or anything. It’s been really exciting to live this way — where we’re all humans. We’re living, breathing things, and we all just want … well, we don’t all, unfortunately, but the people that I know just want to put more love out there. Most of humanity is good, in that sense. Folk music has a way of bringing that out, and bluegrass, specifically, has this way of embracing nature, the beauties of the world, and also the beauties of humanity: feelings, friendship, love.

On your record, those themes might be assumed to be simply, overtly Jewish, but they do fit uncannily within the working language of bluegrass. The parallels are there. I wonder if you feel audiences relate to your music because they already feel these parallels, perhaps not from a cultural Jewish background, but from their own perspectives. Are you seeing that connection happen?

Doni Zasloff: That’s exactly what is happening, and it brings us almost to tears because it’s so moving. After a show, we’ll go into the audience, and it’s so many people of so many different backgrounds. That’s what’s happening with this music, and I don’t even have words to express the gratitude that I feel that it could do that.

Yes, the point is that we’re singing about love. We’re singing about friendship. We’re singing about these universal themes. That’s why we’re singing about them. The little bit of Hebrew in it is our background — it’s so cool to listen to music with different languages threaded into it. It’s a cultural expression.

EL: When we sing Hebrew, we’re celebrating our culture and our heritage. I was talking with Jerry Douglas, during the [recording] sessions, about the Transatlantic Sessions that he’s been leading and a part of for so long, and about how much that’s influenced me. The Scottish-Irish music they create is sung in these ancient kind of Scottish/Gaelic tongues, and it’s never been a barrier to me. I listen to that on repeat.

DZ: To your point, the message is something that we know all people can relate to. On one of the songs, “The Narrow Bridge,” we sing an old saying from the 1800s: “The whole world is a narrow bridge, and the important thing is to not be afraid.” We thought it was a beautiful, poetic saying. We turned it into a story and a song relating to the world right now and how it feels troubled and divided.

I love the lyric in that song, “From the cracks of a barren land, a beauty grows unplanned.” I feel like that’s what roots music is poised to accomplish, especially when it’s dedicated to the idea that we can come from different backgrounds, experience life, and be human with empathy and understanding for stories and experiences that might seem ultra-specific and somewhat forbidding. Have you tried to make what you do more relatable for that purpose? Or does it just work if you put it out into the universe as is?

EL: I think, on the one hand, it works if you just put it out into the universe, but we’re really careful what we put out. Well, not careful, but we really want to write songs that are universal. I think that’s something about folk music — it is universal. It goes back to that thought that we’re all people. There are certain things that we can all embrace and rejoice in about life, in general, while also coming at it from our own different places and different flavors. Like food, it’s a universal thing, but sometimes I want sushi and sometimes I want Mexican. We all have cultures — and beautiful cultures — but they’re better all celebrated in the mix together.

DZ: The magic of bluegrass and old-time music, for us, is that it’s been a way to break down some people’s perceptions. We’re Jewish Americans. This is who we are. I’ve lived here all my life. My mother lived here all her life, and my grandmother came from Poland. I think to be doing “Jewish bluegrass,” we’re quite literally being authentic to what we know and who we are. A lot of people will immediately try to stereotype Jewish music as klezmer music, even when say we play this music they’ll say, “Oh, are you like, klezmer-y?” No! We’re not. Yes, my great-grandmother lived in Poland, but I don’t, so that’s not authentic to me.

You’re making melting-pot music.

DZ: Right. And this is who I am.

EL: Jewish people are an interesting bunch of folks. Throughout all the years of this world, Jewish people have lived in all these places of the world: Eastern Europe, Spanish-speaking countries, South America — we’ve kind of moved all over the place. Historically, we’ve made music in all these different places where Jews have put down roots. In Eastern Europe, what we know as the branded Jewish music is klezmer and that’s because that’s where they lived! Klezmer is actually more of an Eastern European sound than a Jewish sound. For me, it’s interesting that Jewish people have lived in this country for centuries, but we haven’t played these American forms.

I want to shift gears a little bit. In my experience, being gay in bluegrass, if I boil my identity down to just those two communities, I find myself on the margins of both. Gays don’t know what to do with a gay who plays banjo, and bluegrass doesn’t know what to do with a gay who plays banjo. So I wondered … you exist in a very small overlap of the Venn diagram of Jewish identities and bluegrass. Do you feel the tension of being on the fringes of both of those communities?

EL: I do. I totally do. Hearing you talk about it makes me feel for you, because I live in a world — in my own head, and I want the world to be this way — where there are no barriers or lines between people. I was born in Brooklyn to be this Jewish American kid who happened to fall in love with bluegrass music. A lot of that was because my father actually converted to Judaism before I was born. My dad’s side of the family, who aren’t Jewish, all used to live in rural Georgia, and we’d go down there for weeks at a time, when I was a kid, being in the heartland, in Appalachia. With the make-up of who I am — whether it’s my experiences, where I was born, or the kind of melodies that I like — I can’t help but be a Jewish bluegrass musician. That’s just the truth. I think the world’s going to have to catch up to that. Just like you have to blaze your trail — which you are doing — Doni and I have to create, for lack of a better word, a genre around this music, because there’s no textbook for it.

That’s interesting, because in bluegrass, Jewish folks are one of very few marginalized, minority identities that actually have had ongoing, historical representation. From folks like Ralph Rinzler to Andy Statman to Jerry Wicentowski — how do you feel your music connects to that Jewish heritage within bluegrass? Or does it at all?

EL: I love Andy Statman. He’s a master klezmer musician and, obviously, a master on the mandolin. He changed the mandolin game around when Tony Trischka was changing the banjo game back in the ‘70s or earlier. Béla Fleck, by his heritage, is Jewish. Noam Pikelny is Jewish — and I’m not trying to out them in any way — and David Grisman. I mean, I’ve had so many heroes in the bluegrass world and whether they were Jewish or not has had no bearing on that. I’ve always found it interesting, actually, that so many Jews could record gospel music. I’ve always wondered about it with my big heroes. Like David Grisman … how did that work for him?

I think that, over the years, and especially since World War II, Jews in this country have been very silent about who they are, whether or not they’re religious with their Judaism, or just culturally. The biggest case, I think, is Bob Dylan who, in the end, converted away from Judaism, but who is obviously the biggest troubadour and songwriter of our time. He grew up as a Jew in the Midwest. When he moved to New York, he basically copied Woody Guthrie, a very non-Jewish persona. Jews have a hard time dealing with the events of World War II. I don’t have it totally worked out, but there’s something in there.

DZ: And I think that people with Jewish identities have been comfortable being the comedians, and it’s different for a Jewish person to come out and be very authentic. There has been some Jewish bluegrass in the past, but it has all been kind of comedic and not quite the same as us coming from a really soulful place, trying to speak to who we are, own it, share it, and take a different approach.

To get back to this prior question: Do you feel like you have looked to that representation of other people with Jewish identities in bluegrass as an influence? Does your music build on it and expound on it, or do you feel like you’re coming from a different place? A different artistic impetus?

EL: I feel the latter. We’re coming from a different place. I was really only influenced by Andy Statman, personally, and it wasn’t in a Jewish way. I have listened to his klezmer music, but that hasn’t had any effect on my own bluegrass music.

I guess I just wanted to feel out if you thought you were on the same family tree as that tradition, or if you felt you two had planted your own sapling. It sounds like you feel like you have your own sapling growing, which is not a qualitative judgement. I’m not saying you should be one or the other.

DZ: I think that we are just deeply inspired by music. All of our heroes, you know, that’s where the inspiration came. We are just trying to be authentic to the expression of the music that we are so inspired by — like Béla Fleck, and all of the guys on the record. We just make honest music and we’re super inspired by other people who do that.

EL: To sum it up, we didn’t set out to be the first ones, but it kind of weirdly happened this way for us. Nobody has ever recorded any sort of spiritual or Jewish heritage [influenced] bluegrass music of their own making. Either I haven’t heard it, it’s been infused with some sort of klezmer, or it’s been something like a Jew doing a cover of a bluegrass song or a song with Bill Monroe. There have been so many beautiful bluegrass songs that I’ve played through the years — all the Bill Monroe, the Flatt & Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, all the way through Tony Rice, Jerry Douglas, and Béla. I feel like I’m standing more on their shoulders, in terms of the music. I feel like we’re a separate thing.

DZ: Our story is that we fell in love when we were doing this — it’s our love story. It came from falling in love and being vulnerable. We always say this is our baby, this is our life. It came so much from inside of us. We had no plan. We were just falling in love and being authentic with each other. It just happened.

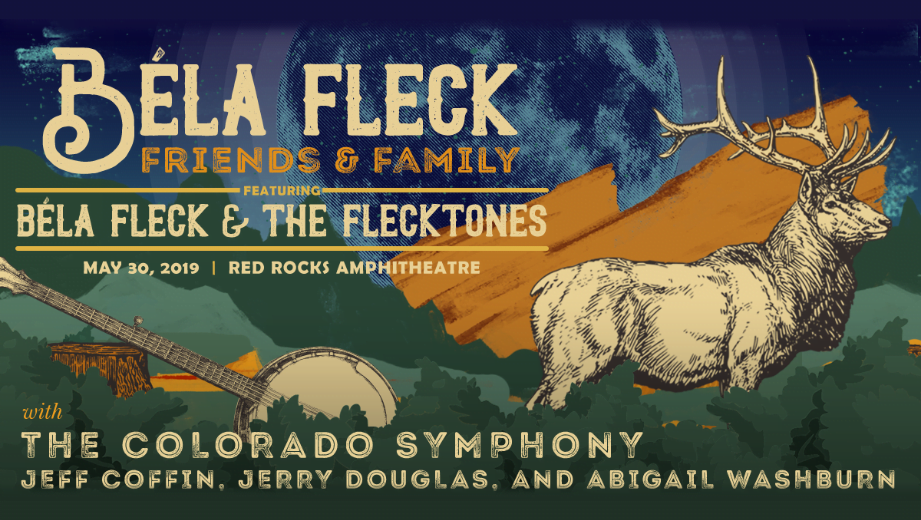

Hangin’ & Sangin’: Jerry Douglas

From the Bluegrass Situation and WMOT Roots Radio, it’s Hangin’ & Sangin’ with your host, BGS editor Kelly McCartney. Every week Hangin’ & Sangin’ offers up casual conversation and acoustic performances by some of your favorite roots artists. From bluegrass to folk, country, blues, and Americana, we stand at the intersection of modern roots music and old time traditions bringing you roots culture — redefined.

With me today in the Writers’ Rooms at the Hutton … Jerry Douglas. Welcome!

Hello. How are you?

I’m good. How are you?

I’m good. I’m having a wonderful week.

Yeah, you’re getting puppies!

I’m getting puppies today! I’m getting puppies today. My granddaughter’s at the house — another puppy, then I’m gonna go see my new grandson on Sunday — more puppies. It’s puppy week!

That’s good livin’!

It is good livin’. I love it.

Okay. Let’s talk about this dobro thing that you’ve got going on.

I’m sorry. [Laughs]

As you should be. [Laughs] What was it about the dobro that first lured you in, so many moons ago?

I don’t know if it was the dobro by itself or the guy who was playing it. Josh Graves played the dobro with Flatt & Scruggs, and he was the one that made me want to become a musician. It wasn’t just the way he played it, because I was hearing Bashful Brother Oswald, at the same time, playing with Roy Acuff and that was good, but Josh Graves stepped up to the microphone and he blew the doors off the place! He could keep up with Earl Scruggs, and he played bluesy, too. He played the blues. I think that was the difference for me, because I was growing up close to Cleveland, Ohio, so I was hearing a lot of rock ‘n’ roll at the same time, and it all worked for me — made the instrument work for me.

My dad had a bluegrass band, but there wasn’t a dobro player within a million miles of me. [Laughs] I told somebody the other day that I stood a better chance of getting hit by a car than to find a dobro. It was not something you saw and they didn’t know what it was. You’d go to a music store and say, “Do you have any dobros?” and they’d look at you like …

But you found each other.

We did.

You’re like Béla Fleck with the banjo, to me. Musically, you guys both do things with these instruments that isn’t normally expected. Who’s leading that exploration — is it you or the instrument? Are you following where it’s taking you?

I’m trying to take the instrument to new places. It’s a great bluegrass vehicle, which has been proven over and over again, with Josh Graves and Mike Auldridge and Rob Ickes. There are several people who really can play one of these things. But I keep exploring and trying to find other ways to use it — in classical music, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll. I created a pickup that works with it that keeps it sounding like a dobro, but you can play to a 24,000-seat place without feeding back. You can compete with a telecaster.

Nice. Do you ever get tired of it and think, “I’m gonna switch to the French horn” or something? Does the mastery ever stop? Is it every complete? Or is there always something new to learn and explore?

There’s always something new. I keep my ears open, and I sort of adapt other things to the guitar. The guitar’s a conduit of whatever’s in [my head], what’s rolling around in there all by itself. It’s a cobwebby place. [Laughs] But I think that I’m kind of trying to lead it from one place to another, but I do get tired of hearing it. I got so tired of it that I started carrying around refrigerator-sized racks of things to make it sound not like a dobro. And then I got tired of that, and I just wanted to hear a dobro again! So it’s a necessary evil.

But I love the sound of the guitar. These newer guitars don’t sound like the dobros did that were on the records that I learned to play from. So I keep a lot of those old guitars around, too. The guy that builds my guitars has actually just come out with a line of guitars that sound like the old guitars. Because, when I play with the Earls of Leicester, I play only old guitars, but he’s got this new guitar I played on the new record with the Earls and no one noticed.

Old sound, new technology. Probably sturdier.

Better construction, yeah. The older dobros, the Dopyera brothers got really lucky. [Laughs] The cone, a lot of things about the guitar haven’t changed since 1927. But the construction has, and how they’re big, beefy, low-ended things that have all these voices that the old dobros didn’t have. But the haunting element, for me, that drew me in in the first place, that’s missing from the big, beefy, hybrid guitars.

…

You mentioned the Earls of Leicester. I mentioned the Transatlantic Sessions and other collaborations, but your latest record is a Jerry Douglas Band joint called What If. Where do you see that album fitting into the wider landscape of your work?

That was really pushing my audience, I think. I quit a long time ago trying to make records for my audience.

I would think you would’ve had to.

I make them for me. I figure, if they really like me, they’ll go wherever I go.

Or wait until the next thing comes.

Or just wait until it comes back around to what you like! [Laughs] I love that record because it’s so big and full. It’s the full band effort with two horns and electric guitar, and everything is on this record. Except keyboards. But John Medeski is gonna play with me at MerleFest! So who knows where we go from there. But I just like the full sound and being able to, more or less, play the band, at this point. It’s dobro driven, and I write everything on the dobro, but everybody gets a little piece of the action.

…

[Tell me a memory of or something you gleaned from] Earl Scruggs.

Earl Scruggs was probably the first thing I remember hearing — ever. Then, when I got old enough, even at five years old, I knew that was good. I knew that was a good sound. It was obvious, just the way my dad would react to it and everybody, before I ever saw him. And then, when I saw him, he was on a pedestal to me, as was Josh Graves and the whole band. That was like seeing the Beatles for me, at six or seven years old, to see Flatt & Scruggs live in Youngstown, Ohio, at Stambaugh Auditorium. I even know what date it was and everything. It was like seeing the Beatles.

And then, I grow up and I move to Nashville and Earl Scruggs becomes my friend. That’s just nuts. But then, to get on the bus with him and be playing in his band, just to wind him up and let him start telling stories … because he was a very quiet man, a very quiet, reserved man. But when he got started telling stories, he couldn’t stop. It was so good! Everything was so good. Every minute, every second that I spent with him, I cherished. I’m blessed to have hung out with and been in the presence of some of these people. And Earl Scruggs is way up there on the top of the heap. There are not many people you can look at and say, “That guy is definitely a legend.” He’s like a George Washington, Abraham Lincoln kind of guy. [Laughs] I haven’t met many of those, a couple others maybe, but he was the first one — the first sound I ever heard and what influenced me in the journey that I’ve had, and what made me take the path that I took.

Well, thanks, Earl.

Thanks, Earl. Gee-whiz.

Watch all the episodes on YouTube, or download and subscribe to the Hangin’ & Sangin’ podcast and other BGS programs every week via iTunes, Spotify, Podbean, or your favorite podcast platform.

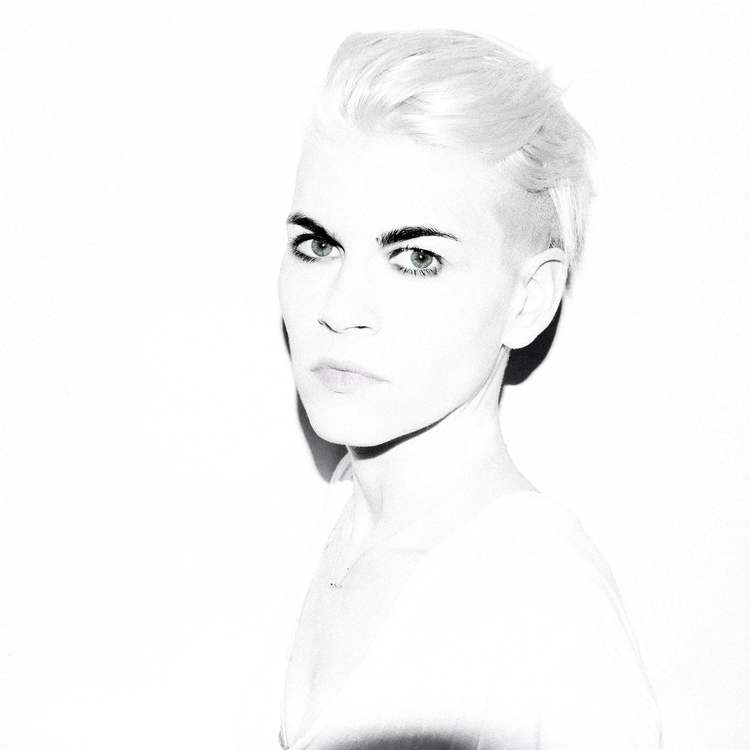

The Language of Music: Kaki King in Conversation with Dan Tyminski

“One of the worst ice storms in my life was in Nashville,” says Dan Tyminski. “Go figure. I grew up in Vermont, and I had to go to Tennessee to get the ice.”

Kaki King remembers that ice storm, because she was stuck in the Volunteer State, as well. She had two nights booked at OZ Arts, a venue just outside of Nashville. “The night before, everything was fine. We set up everything, all of our gear, then went back to the hotel. We ended up getting trapped there for two days. We could make it to the highway, but we couldn’t get our stuff!”

These two instrumentalists may come from very different musical worlds, but their experiences during ice storms — and not during ice storms — are actually very similar. Tyminski is a bluegrass veteran, playing countless festivals as a kid and serving as a lynchpin with Alison Krauss + Union Station for a quarter-century. King, on the other hand, spent her teenage years playing in pick-up punk bands before developing a very complex playing style that treats her acoustic guitar like a drum set.

And yet, both of them kick and push against the strictures of their chosen genres, constantly ripping it up and starting again. Tyminski is most famous to younger generations of listeners for his collaboration with Swedish DJ Avicii, and on his new solo record, Southern Gothic, he mixes country and bluegrass with EDM production techniques and looped beats. And King recorded her latest album, Live at Berklee, live at Berklee, with a small orchestra of student musicians filling out new arrangements of old compositions. Both releases are outliers in catalogs full of outliers.

First of all, do you know each other? Are you familiar with each other’s work?

Dan Tyminski: Just a little bit.

Kaki King: I know a little bit about you, Dan, and the things that you’ve done.

DT: I just did a little bit of recon before the call. I heard some wonderful guitar playing, and then the phone rang.

You’re both known for your guitar playing, but you’ve both released albums where that instrument takes a back seat to these larger arrangements.

DT: It’s funny. On my album … I actually opted out. This is the first album I’ve done where I really opted out of the playing. I had Jesse Frasure produce this record. We were going down a different avenue of sound and, when he was putting together the band to track all of this stuff, I really felt like I would have a better chance of getting in the way from having him have the freedom that he needed to explore. So, I really stayed out of the playing on most of my record. I’m on new ground, where I let someone else come in and do it all.

KK: That’s cool.

DT: The bad part is, now I have to learn how to play all this stuff. And, it turns out, that some of it is hard.

KK: The idea for Live at Berklee was to put together an ensemble and reimagine a bunch of older tunes with strings, and brass, and woodwinds — and then do it live. This wasn’t the kind of thing we wanted to go a studio and make perfect. The liveness of it is what’s exciting. For me, it was doubly hard because, on one hand, I had to write a few arrangements, which is out of my wheelhouse. But I enjoyed it. And then … I had to go to college. I was working in a classroom with a conductor and 13 really good players. I never went to music school, and I haven’t been conducted since I was in high school band. I really had to buckle down. It challenged my guitar playing to be able to keep up with these really great players. It wasn’t something where I could do this freeform thing that I do, or change the tempo, or drop a measure. I had to be perfectly accurate every time.

DT: From what I heard, it sounds like it was no problem whatsoever. It does not sound like you were struggling.

KK: Well, thank you. The end result was fine, but the initial rehearsals were a bit like, “Oof. This is gonna be a hell of a ride.”

DT: In a way, it’s somewhat similar, playing the live stuff on my album. This is the first time in my life where I’m playing with some tracks. It’s a very strict arrangement and, if you veer off at any point — miss a bar, add a bar — it’s a train wreck. I’ve never had to pay so much attention, and I am easily the weak link of the live band version of all of this new stuff.

It sounds like these two projects kind of forced you not to improvise.

DT: I can definitely say that what she’s doing is much more difficult. Most of the effort in what I did with Southern Gothic was in the creation of the music, and then I was able to let someone else take the reins. Whereas, it sounds like you had to really step up to the plate and get outside the comfort zone a little bit.

KK: Well outside my comfort zone. But there was really no improvisation. I’ve been working with strings and arrangers for about five years, in one form or another. Every couple of months, I’ll get a gig with a string quartet or do a little tour. And, each time, I learn something new. It always is along the theme of, “You can actually change that. You can give directions. Just because you didn’t go to music school and you’re not the brightest kid in the class, doesn’t mean you can’t say, ‘Don’t play that.'” The process, for me, was learning how to sit in an ensemble and play a song I was familiar with but not to deviate too much from my original arrangement. But there was constant conversation and feedback among the musicians and the conductor.

DT: What a beautiful thing to get into a situation like that, where you have that type of canvas to work with. It sounds like we did the same exact thing, but we just did it so differently. You had string sections with people working together, and I had one guy trying to say, “Okay, now this is where the string sections are, and let’s do this.” I’ve got someone creating these string sections on a computer, which then we later went back and had live people play. It’s a weird process. But there are a lot of ways to get there.

KK: That’s what people want to hear, especially people who are being trained now. They realize that the people they play with are not all going to have the same background.

DT: What matters is, does someone have a vision? And is it translatable?

What are your backgrounds? Are you both self-taught? It sounds like you’re taking very different approaches that maybe aren’t the norm for people.

KK: I can’t find anyone who does the norm anymore.

DT: I was gonna ask, “What is the norm?”

Fair question.

DT: There are so many ways to get there — even when it comes down to writing the songs. Of all the different songs that have made their way onto this project of mine, no two of them came about the same way. They all started differently. They were all from different conversations. Some started lyrically and we found music. Some started with music and we found lyrics. Yeah, there is no normal. There’s just, “Does something make you feel what it’s supposed to make you feel?”

KK: I can certainly say that all my previous records started with a riff here, a drum thing there. Some songs wrote themselves in an hour. Some songs took a year to get out. I cannot sight-read guitar music, and since I play in different tunings anyway, it would just be … Well, there are, like, two people in the world who can sight-read guitar music in different tunings, and they have social problems. I am fortunate that I understand enough about music, and about intervals, and about turning a major into a minor to be able to convey that style of information to other players. I was fortunate enough to just be given enough basic information to have something like this not just explode my brain.

DT: I had this conversation with someone earlier this morning, but I would have loved to have spent some time on a theory and be able to verbalize things. But anything you ask me to do, there’s a reasonable chance I could do it, if I hear it. But there’s nothing that I can see or hear explained that would get me there. I have to hear it.

KK: Everyone comes from a different background. I’ve seen enough to know that no one who has serious musical training is going to judge you if you don’t. They’re very accepting of talent or excellence in all of its form, even if it’s a very simple thing that you do.

DT: That’s the truth. I’ve never run into it as a roadblock or something that’s stopped me from completing my gig. On a personal level, it would be nice to feel like I was more in tune with changes that are going on. I’ve found myself in settings before, playing with orchestras, and having people say, “Could we try this and this?” I hear it all going down, but I have to wait until it passes before I understand what was said. It would have been nice to have a little training.

KK: It’s never too late.

DT: Well, I’m starting to think that way now. Maybe it’s time to get back to the drawing board.

But you two have both been challenging yourselves throughout your careers, right up to these new albums.

DT: Any time I’ve ever stepped outside of the box, or any time that I’ve heard other people stretch beyond what I normally hear them do, it’s always been rewarding. I’ve always been happy when I’ve made myself uncomfortable, when I put myself in that weird spot where I had to dig, you know? And when I hear other people do it, I feel the same thing. There’s a reward there. It’s easy to stay in your little box and do what you’ve done before. But when you stretch, that’s when you really get to discover who you are.

KK: I couldn’t agree more. In some strange way, I feel the most comfortable when I’m uncomfortable. I had done two solo guitar records in my early 20s, and I’d already had a lot of success, even though I didn’t really know what was happening to me at the time. But the last thing in the world I wanted to do for a third record was another solo guitar record. I just couldn’t fathom it. So I made a record that was a little more than half-instrumental. I worked with John McEntire from Tortoise, who’s a very post-rock kind of producer. We played a ton of different instrumentation and a lot of electric stuff, which was outside the box for me, at that moment. Each subsequent album started to take on a different hue. Prior to doing the Berklee thing, my last project was a multimedia show integrating video lights to the guitar and having the guitar control what you see.

DT: There’s something in the whole process of creation that people can connect to. I’ve been a big advocate of live music my whole life. For me, there’s all the room in the world for recorded music, and people need that in their lives to take home and be able to turn something on. But I’ve found that, when I watch something being created in front of me, it touches my soul in a different way than when I hear recorded music. So, when you say your guitar can control what people see with your lights, that’s beautiful. That’s the missing element to what you get when you just hear recorded music. When you get to see the effect of what’s being created right there and feel that new emotion … oh man, there’s just nothing else like it.

KK: I agree. Especially when I see a group of people playing together and I know they’re all feeling it, and they’re hitting their stride, it doesn’t get better than that. I’ll never hear that on any record. I’ll never see those musicians onstage smiling at each other. People getting in the zone is such an incredible thing to watch, and it’s an incredible thing to feel when you’re doing it.

DT: There’s nothing else like it. There’s nothing to compare it to.

KK: I’ve been playing my whole life — since I was a little kid. I grew up playing in bands and I was normally the bass player or the drummer, but I have this strange thing happen where I can be in a room with a bunch of people, men or women, who I normally don’t want to hang out with. Maybe our tastes run a little different, but something brought us together musically. Especially as a teenager, when we would play songs that we all wrote our own parts for, and then we play them together perfectly, all of a sudden we’re sharing the same heartbeat. It’s weird, because these are guys who would otherwise be making fart jokes or talking about some stupid movie. That has rung true throughout all types of ensembles that I’ve played with.

DT: Exactly. Music is its own language. I’ve been with the same group of people for 25 years, and what we have is rare, in that we have five people who truly love music for music’s sake. Everyone is able to listen and respond. It’s a language that you speak with each other. You can be upset with somebody in your personal life and still speak words of love, musically. When you have people who you can communicate with that way, there’s beauty in music. There’s a language there that you can only hear through it being played.

I definitely think music, as a social medium, is very important right now. Not to get political, but when things are so divisive, anything that brings people together from different backgrounds is a pretty profound vehicle.

DT: It always surprises me. I remember the last time I was way outside of my comfort zone: I had gone with Jerry Douglas to Europe to do Celtic Connections, and we decided we were going to play a couple of songs we’d been playing for a while, but all of a sudden we’re playing with whistles and pipes and accordions. And I was looking at Jerry thinking, “Why would we choose this song? How can this even work?” But then I realized that we were all speaking to each other through the song? It’s like someone who spoke Chinese or French or some language you didn’t understand, but yet you knew everything they were saying. That’s how I felt with being over there. We were speaking in different tongues, but we were communicating. There’s a beauty in that.

Even just being in a crowd and watching an artist playing, I know I’m having a similar experience to the stranger next to me.

DT: Songs definitely hit everyone differently, as they listen to them. Depending on the mood that you go in with, you can draw completely different conclusions out of what you’re hearing. That’s one of the things I love about listening to music. It speaks to you in a way that nothing else can. Music has saved me, my whole life. It’s been my food. If I’m happy, I play music. When I’m sad, I need it even more.

KK: These days I’m more often the person on stage than the person in the audience. I wish I could flip that ratio because I love going to see live music. I’ve just got two young children right now. Recently, I had a friend named Matt Sheehy come and open shows for me in a couple of towns. I’d been listening to his music for a long time and I think he’s amazing. We first toured together in Italy, years ago. On this recent tour, he started to play this really beautiful song, uplifting in a lot of ways, and it took me back 10 years to listening to him play in Europe. I was suddenly a decade younger, and I was just sobbing. I was seated to the side of the stage and the lights were on me. I wasn’t trying to make a scene, but I found myself just bawling my eyes out. The acknowledgement of time passing, the feeling that something about this music and this feeling is eternal … it was a profound experience.

DT: That’s amazing. That’s what music should do.

I feel like I’ve talked to a lot of people recently who’ve said similar things. At a certain point, they find themselves playing more shows than they see, so they try to find ways to flip that around and become part of the audience again.

KK: I don’t know if you feel this way, Dan, but when being in a venue is your job and you’re backstage, I get really spoiled. There are a lot of shows I want to see, but then I think about buying a ticket, standing in line, being in a crowd. Then it becomes the last place I want to be. It’s something that’s severely lacking from my life, that I have been really missing.

DT: I share that with you. All the live music that I’ve heard, by and large, most of it was before the age of 16. From the point of being 15 or 16 years old on, I’ve always been the one on the stage, so attending shows … I can count on my two hands every show I’ve been to as an adult. It’s less than 10. Less than 10!

KK: We should go to more shows, man.

DT: I know. Going to more shows is on my to-do list. I should definitely be spending more time in the audience.

Kaki King photo credit: Shervin Lainez

Tommy Emmanuel: Swinging for the Fences

There’s a moment at the beginning of “Saturday Night Shuffle” — one of 16 duets from Tommy Emmanuel’s new album, Accomplice One — where the song’s guest, Jorma Kaukonen, turns to his host and says, “You’re a badass cat, man.”

It’s a nod of approval from one guitar great to another. Accomplice One is filled with those unplanned exchanges: a shout of encouragement here, a surprised laugh there. Raw and real-sounding, the album feels like a jam session between friends, mixing off-the-cuff solos and first-take performances with the virtuosity of an instrumentalist who’s been doing this for a long, long time.

Emmanuel began touring more than a half-century ago, hitting the Australian circuit as the youngest member of a family band. Now 62 years old, he still plays 300 shows a year. He doesn’t use a pick. He doesn’t use a regular amp. In a world whose most well-known guitarists — Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Chuck Berry, and the like — inevitably tend to be electric players, Emmanuel has remained true to the acoustic guitar. He’s the king of the unplugged.

With appearances from 20 guests, Accomplice One shows just how far the king’s empire extends. Americana poster boy Jason Isbell joins Emmanuel on the album’s opening track, a soulful reimagining of Doc Watson’s “Deep River Blues.” Bluegrass heavyweight Jerry Douglas stops by to swap solos on Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze.” Mark Knopfler, Ricky Skaggs, and Rodney Crowell all make their own cameos, too. Recorded in studios across the world, these songs nod to the core ingredients of American roots music — Emmanuel’s bread and butter — without losing their global perspective.

“I grew up with music that came out of America more than the music that came out of Australia,” says Emmanuel, who was raised in New South Wales. “It was a combination of sounds that were coming out of Nashville, Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City, and New Orleans. I love all kinds of music, but that’s still the stuff that really touches my soul.”

Those childhood influences resurface on Accomplice One. “Saturday Night Shuffle” flips the Western twang of Merle Travis’s original on its head, sounding instead like the funky work of a New Orleans jazz band. Madonna’s dance-pop hit, “Borderline,” is turned into a lilting folksong with help from Amanda Shires. Emmanuel trades country licks with banjo phenom Charlie Cushman and blues-rock guitarist J.D. Simo on “Wheelin’ & Dealin’,” then bounces between Celtic shuffles and barn-burning bluegrass on his Clive Carroll collaboration, “Keepin’ It Real.”

It’s during “Djangology,” though, that the album truly goes international, with Emmanuel and his guests looking far beyond the Lower 48 for inspiration. A tribute to Django Reinhardt’s laid-back, jazzy phrasing, the song was recorded alongside Frank Vignola and Vinny Ranioloa in Cuba, during the middle of the country’s first-ever guitar camp.

“I was teaching 120 international students — everyone from 18 years to 80 years — for four days, and playing shows at night,” Emmanuel remembers. “One of the days, we went to the studio where they recorded Buena Vista Social Club. All the original microphones were there. We brought in some plastic chairs, and all the students sat in the main orchestral room. We had mics set up in front of us, and we worked out the arrangement in front of the kids. Then we recorded it twice and played it back, so they could hear it. The second take was the best, so that was the one we kept. It was very simple.”

Remember Santana’s Supernatural and its biggest hit, “Smooth,” which paired the guitar legend with Matchbox 20’s Rob Thomas? That song was inescapable for years, but it never truly sounded believable. Did anyone actually think Santana and Rob Thomas hung out together? Could anyone imagine them co-leading a guitar camp in Cuba?

That’s what makes Accomplice One so compelling: It’s believable. There’s fret noise on these tracks. There’s studio chatter between the musicians, all of whom are fans of one another. During the Cuban recording, you can hear someone tapping a foot on the studio floor, unable to resist keeping time with the music. The imperfections that would’ve been bulldozed by Supernatural‘s high-gloss production are, instead, put on a pedestal and celebrated by Emmanuel, whose album emphasizes feeling and intention over perfection.

That said, there’s a good bit of perfection here, as well. Emmanuel attributes his refined playing to a lifelong Chet Atkins obsession, which brought him face-to-face with — and eventually under the wing of — his idol during Atkins’ later years.

“Chet lived a life with a lot of great experience,” says Emmanuel, who became friends with the guitarist in 1980. “He had a lot of great people around him. He didn’t just make great music; he made the people around him great, too. He taught me a lot, not just about music, but about human nature. That’s the stuff I can write about.”

Nearly two decades before they met in Nashville, Emmanuel first head Atkins on the radio in 1963.

“It was a sound that I knew, deep in my soul, was what I wanted to make,” he remembers. “I wanted to sound like that. I just wanted to be like that. I think it’s nature’s way that all of us start out emulating somebody.”

If Emmanuel’s approach to the guitar began as emulation, it’s since grown into something signature. Like a one-man band, he’s learned to simultaneously pluck out a song’s melody, underscore it with a walking bass line and beef up the mix with accompanying chords. Listening to “Deep River Blues,” it’s easy to assume that Emmanuel and Isbell are tag-teaming the song’s guitar duties, filling its verses with blue notes and densely stacked chords. But that’s Emmanuel playing alone, with Isbell opting to leave his guitar in the case and, instead, channel his inner soul singer.

“When Jason started to sing that song, you’ve gotta imagine the chicken skin I got,” says Emmanuel, happy to refocus the spotlight on Isbell’s voice rather than his own playing. “I was doing the thumb-picking Doc Watson part and, when you add his voice to mix, it’s totally a soulful experience. It’s real, and that’s what I love about playing music.”

The feeling appears to be mutual. Accomplice One is filled with the sympathetic interplay of musicians who want to be there and that’s what elevates it above the usual catalog of guitar-heavy duets. Filled with covers, originals, (“Rachel’s Lullaby,” a Beatles-inspired song written for Emmanuel’s baby daughter, is one of his most compelling compositions in years.) and top-shelf playing, the album is for guitar nerds and casual Americana fans, alike. It’s the sound of a roots music lifer who, a half-century into the game, is still swinging for the fences.

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.