Willie Nelson has long been not just an American musical treasure, but an iconic figure with far more appeal across racial and generational lines than often recognized. At 87, he’s achieved a perfect marriage of artistry and commercial success few have in any idiom. While certainly a country legend, and the only person in the genre to ever achieve a Top 10 hit in seven different decades, he’s also collaborated with an astonishing number of artists across a wide swath of musical styles and approaches. He’s penned numerous anthems that have been covered by jazz, blues, R&B, soul, rock and pop vocalists, and this month he released his 70th studio album, First Rose of Spring.

Nelson’s never been afraid to stand up for social justice, even when those words weren’t part of the popular vernacular. Early in Charley Pride’s career, Nelson actually gave him a kiss on stage in Louisiana, quieting an audience that was allowing some of its more verbally racist louts to heckle Pride on stage. He’s always included Black musicians in Farm Aid concerts, had one of his biggest albums ever (Stardust) produced by a Black man (Booker T. Jones, who raved about Nelson in his autobiography) and has maintained a friendship with Snoop Dogg since long before Lil Nas X appeared on the scene. He also enjoyed a very close relationship with Ray Charles, who Nelson lamented he could never beat at chess.

He’s in the same company with people like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Bill Monroe, whose output, personality and consistent brilliance has endured despite changes in production, audience preferences, and many other variables that can negatively affect the careers of popular musicians. Part of the reason for that longevity is Nelson’s undeniable skill in multiple areas. He’s penned a host of songs that are every bit as epic as those from the pre-rock canon he often samples. Had he only written “Crazy,” “Funny How Time Slips Away,” or “On the Road Again,” that would have been enough for one lifetime. He’s also a very credible singer, highly effective in pacing and telling a story.

Nelson has consistently embraced and operated in other genres by neither sacrificing his musical individuality and integrity, nor seeming to pander or simply attempting to seem hip. Actually, he’s the epitome of that term, though in a vastly different way from someone like Miles Davis, who was known as much for fashion and fine cars as musical innovation. The fact that Nelson has appeared in more than 30 films just adds weight to his universal appeal.

Trying to pick the best of Nelson’s numerous collaborations with great Black singers and musicians is a tricky thing. One could easily select 10 one day, then come back and tab a different 10 another time. But these are some (far from all) personal favorites. They are ranked in order only by year, nothing more. We picked a mix of singles and LPs, but it’s just a small sample of the many wonderful things he’s done. By no means would we claim this is the definitive list for Willie Nelson’s collaborations with African American artists, but it’s a good sampler and an indicator of how widespread his impact and willingness to work with various musicians actually extends.

SINGLES AND ALBUM CUTS

“Man With The Blues” with Buckwheat Zydeco

From Five Card Stud (1994)

The greatest zydeco master since Clifton Chenier teams with Nelson for a smoky, delightful romp that sees Buckwheat Zydeco also find a comfort zone vocally and instrumentally. As is always the case, Nelson easily works himself into the arrangement, and the two sound right at home in this setting.

“Night Life” with B.B. King

From Deuces Wild (1997)

The King of the Blues sounds happy and engaged on one of Nelson’s earliest compositions, providing some taut guitar licks and outstanding lead and harmony vocals while Nelson doesn’t try to match the improvisational edge, instead easing into a nice zone that’s part complimentary, part quite different in style and sound, but ideal for the situation.

“Still Is Still Moving to Me” with Toots & the Maytals

From True Love (2004)

Toots brings some Jamaican soul and lots of energy to this collaboration, while Willie seems a bit more energetic as the song works its way through. This is one of many performances that earned this LP the Reggae Grammy, and Nelson had such a great time he made a follow-up of his own and paid Toots and company back by having them guest on it.

“Busted” with Ray Charles

From Genius & Friends (2004)

I know “Seven Spanish Angels” was a number 1 hit and more people remember it fondly, but this late redo of an early Charles hit has equal doses of warmth, reflection and edge in both voices. Charles was certainly not at his vocal peak, but he found a way to make his treatment effective, while Willie as always proves the ideal partner in multiple ways.

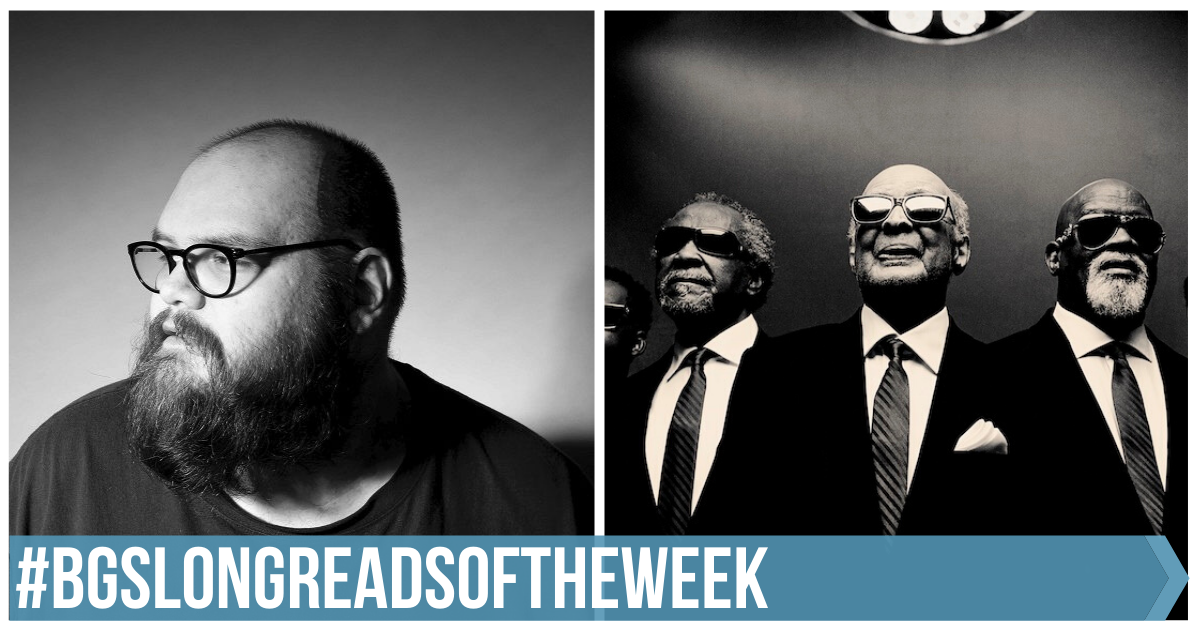

“Family Bible” with The Blind Boys of Alabama

From Take the High Road (2011)

The album title indicates precisely what Nelson does here, singing with verve and fire while the Blind Boys bring some of their characteristic Golden Age gospel energy and intensity to this rendition that’s alternately wistful, memorable and poignant. This composition dates back to Nelson’s late ’50s catalog, while he was trying to get heard as a songwriter.

“Grandma’s Hands” with Mavis Staples

From To All the Girls (2013)

Mavis Staples has one foot in the church and the other in the street with her customarily powerhouse voice setting the tone. Nelson manages not to get overridden or canceled out in the process as they do their own special version of the Bill Withers hit, which the Staples Singers cut for their 1973 Stax LP, Be What You Are.

“Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream” with Charles Lloyd and the Marvels

From I Long to See You (2015)

The great Memphis jazz man Charles Lloyd and his newest group provide the backing for what comes off as a cross between a nightmarish vision and a marvelous revelation, sung in emphatic fashion by Nelson and punctuated by Lloyd adding some nifty licks underneath and the Marvels adding some musical punch.

ALBUMS

Country Man (2005)

A follow-up to his appearance on Toots’ LP the year before, Nelson goes full bore into reggae territory. Some of it works, some of it doesn’t, but all of it is performed with enthusiasm and joy. Nelson vocally handles the skittering reggae rhythms well, and on the disc’s best songs surpasses what he did on True Love.

Two Men and the Blues (2008)

Wynton Marsalis as a youthful prodigy had a lot of negative things to say about a lot of things back in the ’70s and early ’80s, and country music wasn’t spared in his broadsides. But fast forward all these years later and his gorgeous trumpet solos (both full and muted) made a great musical partner and support system for Nelson, who by now was so familiar with pre-rock, blues, and even traditional jazz tunes and rhythms that it was super smooth sailing from first note to the end. Also recommended: the DVDs Live From Jazz at Lincoln Center with Wynton Marsalis (2008) and Willie Nelson & Wynton Marsalis Play the Music of Ray Charles (2009).

Here We Go Again: Celebrating the Genius of Ray Charles (2011)

Marsalis and Norah Jones joined Nelson to pay homage to his friend Ray Charles, doing wonderful renditions of both hits and more obscure Charles tunes before a rousing audience. Nelson sounded especially energetic throughout, while Marsalis, who’s often been accused of being more technically expert than emotionally powerful, delivered crushing solos and accompaniment, and Jones was equal parts alluring and engaging. As always, Nelson comes across as sincere and genuine, a marvelous mix of down-home sensibility and attitude.

Photos: Pamela Springsteen