Back in March, the Avett Brothers — Scott and Seth Avett, along with bassist Bob Crawford — were scheduled to leave their homes in North Carolina and head out West, where their longtime producer, Rick Rubin, was waiting at his studio in Malibu. They were in a prolific place at the top of the year, and eager to keep up the momentum. They had just released Closer Than Together, their tenth studio album, in October 2019, and had written and recorded The Third Gleam, the latest chapter in a series of acoustic EPs. They had also written a ton of new material — enough for another album, by Scott’s estimation — and were all set to move forward with it when the coronavirus hit. Everything, including their flights to California, ground to a halt.

The only thing that’s gone according to plan for the Avetts in 2020 is The Third Gleam, and it’s weirdly fitting — fateful, even — that it’s a homecoming in many ways. The eight-song EP was ushered into a tumultuous time they never saw coming, one that’s forcing everyone to stay put, slow down, and count their blessings more fervently than usual. It’s a return to the sparse acoustic arrangements that the Avetts perfected in their early releases before they teamed up with Rubin in 2009 for their mainstream breakthrough, I And Love And You, which brought them into the rock arena.

The Second Gleam came out in 2008 just before I And Love And You changed their lives and their sound, and though they’ve never strayed from their bluegrass and folk framework, they haven’t returned to the simplicity of Scott and Seth working through ideas with only their guitars and each other for company to this degree in over a decade. (Crawford does join them on The Third Gleam; he wasn’t brought in for the first two.)

Each song is striking in its approachable yet profound sincerity, and this less-is-more approach is one they found to be particularly effective in this fractured time. These issues were on their minds before the coronavirus upended life as we know it, but the Avett Brothers find themselves finding new meaning on The Third Gleam back where they started: at home, in North Carolina, trying to make sense of the world with little more than two voices and two guitars in sharp relief. For Scott, it’s simple: “The smallness of the Gleam — that’s where its power is.”

BGS: When I think of the first two Gleams, some of the saddest songs you’ve ever written come to mind, like “If It’s the Beaches,” but also gems that became fan favorites, like “Murder in the City.” How do The Gleam, the Second Gleam and The Third Gleam stand out to you? What sets them apart from the rest of your work?

Scott Avett: If there was a heart or soul or spirit to everything we do, [The Gleams] orbit a bit closer to that. If there’s layers to an entity or a life, this is kind of at the pure center of it. I’m coming up with this theory for some reason right now with you. [Laughs] At the root of the songs, a lot of the songs on other releases, we have wrung them out — put them literally through the wringer — to see what they want to become, what they can become, what we’re trying to hear and get out of them. Are we challenging them or going too far with them? With these, we don’t ever take that journey. It’s much earlier in the inception of the life of the song that we stop meddling with them. There’s a little more to just be with them, which is at the root of things.

Seth Avett: The series itself sort of represents a simplification across many aspects of this whole thing. It represents the clearing out of many great things, many great tools, and many great advantages we have with our band and our resources, and our possibilities. It simplifies the process of collaboration, the process of artwork. It simplifies recording, mixing, mastering and everything else. Across the board, it’s just a process of simplification and reduction, to where the only real star is the lyrics. I think that we’re still attempting to make something that’s engaging, musically, but it’s no secret: what we put our time into is storytelling, writing words and then sharing them onstage. It’s always at the heart of our songs, and so the Gleam is presenting only the heart rather than the entire body in a way.

Bob Crawford: They’re Scott and Seth’s sketchbooks, really. If you knew these guys as well as I do — and I know a lot of people know them very well, because they put it all out there and they always have — but if you love a great painter’s paintings, and you become a connoisseur of that painter’s paintings, their sketchbooks are widely available nowadays, be it Rembrandt or Leonardo da Vinci. That’s how I look at the Gleams, stitched in with the fabric of all our work: they’re basically more broken down, raw thoughts that they guys have. They’ve always wanted these things to be quieter and less. This is the first one, I think, I’ve played on; normally it’s just Scott and Seth doing these. It’s just a chance for them to get quiet, be alone, and be brothers.

Seth Avett: What it does for me, personally, is it takes a new inventory of our trust, of our brotherhood — my trust for Scott and his trust for me — with no other real considerations. It’s wonderful to be reminded in such a genuine way, with such gravity, that we still trust each other completely, and we’re not moving forward based only on the efforts of others. We still have each other’s trust and care, and we still hold those things in the highest regard. It’s a funny thing: on the first two Gleams and on this one, when we go into the process of finding out what the songs are going to be, and we present them to each other, there’s very little discussion.

All these full-length records, whether one person wrote the whole song technically or not, the other one will have a certain amount of contribution to it. There’s a lot of weighing: “What does it mean?” “Can it be said better?” “Is this too much, is this too little?” We do consider them in a big way, and we consider the songs on the Gleams in a big way as well — but we hardly talk about it. It’s like, “Hey, here’s four songs that are feeling really good to me and things I want to say,” and the other brother says the same, and that’s it. We just do it. It’s cool.

Bob Crawford: These Gleams give them an opportunity to come together and work together a little more than they have in recent years. We’re coming full-circle because of the pandemic. Since the pandemic, they’ve been living very close together and spending more time together. They were always close as brothers and best friends, but closer, approximately, so they could get together. We were actually about to go to Malibu to record the week the pandemic hit, the week of the shutdown. Ultimately, we tried to do it all these different ways; it just didn’t work out, so it turned into them recording demos themselves, sending me the demos, and me recording the bass and sending them back.

Scott Avett: What’s different about mine — and this is a change for Seth and I — we sort of switched places. Several years ago, I probably would’ve been the one that tended to be more rapid-fire, more erratic. I just chop it up with a lot of syllables and a lot of words. On this one, we switched. We were laughing about it. Seth’s songs have a lot of words and tell stories, they’re narrative, and then mine are very much personal and have a lot less words and a lot more space.

I always look at it that there’s only one character on the record, there’s one character in the story, and the two of us kind of make that character. We would do very different things on our own, probably. There’s a contrast to it, a gemini sort of approach to it I guess. [“I Should Have Spent the Day With My Family”] is a good example of what’s changed for us. It’s minor and subtle to anybody else, but it’s a change for us.

Seth Avett: If you look at The Third Gleam, it’s impossible not to compare and contrast between me and Scott — I know it is, I’m sure all of our fans do it — where the differences between the Seth and Scott songs have never been more laid bare, in terms of the difference of the vibe. Scott’s songs, they just have so much space and breadth in them. I don’t look at “Family” or “Fire” as songs that have a ton of breadth in them; they feel a bit more urgent.

The narratives have a bit more of an agenda. Whereas, “I Go to My Heart,” “Victory,” “Back into the Light,” they have quite a lot of breadth and space, and so I’m seeing a change in him. If we are writing the songs we’re meant to write, and we are giving reverence to our form, then the changes in us are the changes in the song. If you ask, “How have I seen his writing change?” I’m thinking about how he is growing and changing, as a man, as a father, as a brother. It’s all kind of wrapped in one.

Seth Avett: I can’t say that there was a point where I said, “Okay, now I’m going to open the door and start writing these types of songs.” This sort of happened incrementally. A song like “Bang Bang,” there were multiple moments where I’d go to a hotel room, and I’d turn on the television, and it’s just one [show] after the next, from ridiculous garbage to the most eloquent sci-fi — but it’s always the leading man with the gun. It’s always presented with such power, and it’s just ridiculous. The idea of holding a gun to make someone powerful is absurd; it’s preposterous.

I had many moments like that, and then there were many shootings. “I Should Have Spent the Day with My Family” is an obvious, super-literal reaction; “We Americans,” that’s the first four years of a person’s life growing up as an American. I don’t know that there’s one moment where I gave myself permission, but there have been many moments that I consider wholly unavoidable in terms of taking that into the songwriting.

This has been a tumultuous time, so I was curious if you think there’s a connection between that and going back to the foundation with an acoustic EP. Do you find that it was an organic thing to take a step back and retract to that nucleus and get to the root of all things Avett with The Third Gleam, considering everything going on?

Bob Crawford: It’s definitely a time of reflection, and it does make you appreciate all we’ve done, because you don’t know when and how we’re going to do it again. … For me, “Victory” is the greatest song they ever wrote. We only win when we submit; we only find peace when we let go. How do we hold it all together in our hearts at the same time? How do we not lose our minds at that? How do we find true peace inside while there’s chaos flowing back and forth? I think, hopefully, the Avett Brothers can be part of the center of that. If you are the center of that, you’re not polarizing. You can’t alienate anybody. No matter what you know they believe, face to face is how we live the gospel, how we can make real change.

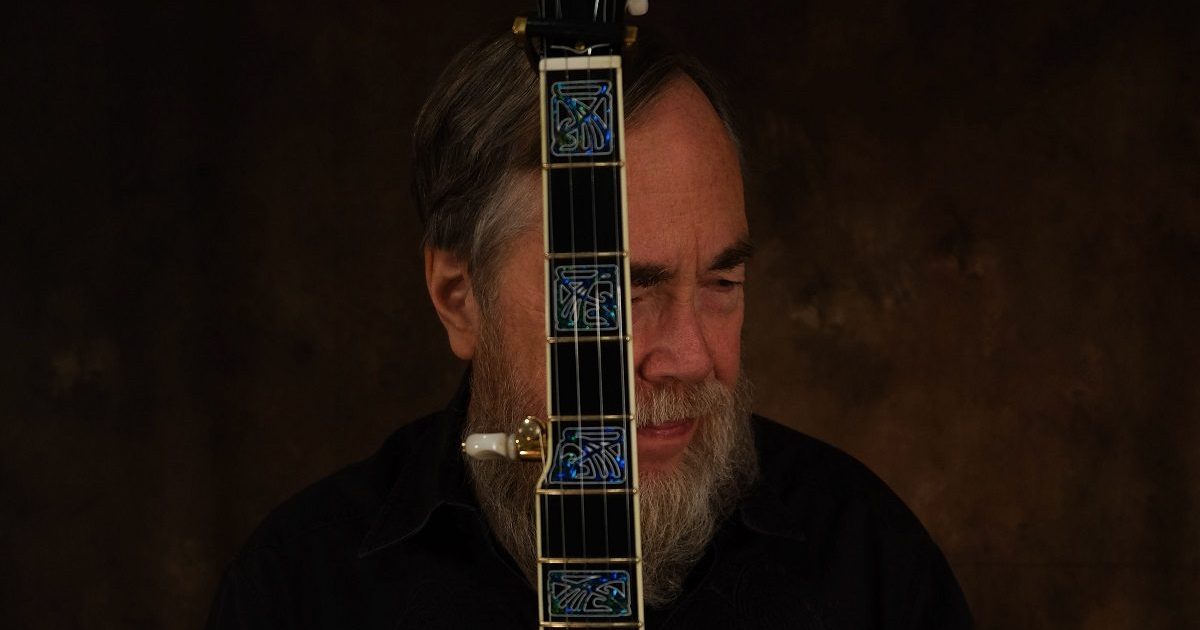

Photo credit: Crackerfarm