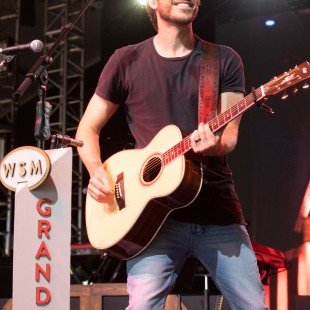

John Paul White, who rose to prominence as half of The Civil Wars, has just delivered his most fully-realized solo set, The Hurting Kind. When he couldn’t find a modern album that gave him the feeling of his favorite countrypolitan recordings of the ‘50s and ‘60s (think Patsy Cline and early Roy Orbison), White set out to make an album that would capture the aesthetic of that era without going full-on retro. He wrote with some legendary songwriters of those decades still working in Nashville, including Country Music Hall of Fame members Bill Anderson and Bobby Braddock. One of those Braddock collaborations, “This Isn’t Gonna End Well,” is included here as a duet with Lee Ann Womack.

Recorded at his own Sun Drop Sound studio in Florence, Alabama, with producer Ben Tanner (Alabama Shakes) behind the console, The Hurting Kind finds John Paul White going for broke as a vocalist, flexing his creative muscle as a country songwriter, and speaking his mind about what it means to live and work in Alabama in 2019.

BGS: When you were growing up, your father’s record collection contained a lot of classic country albums, but you didn’t gravitate towards those sounds back then?

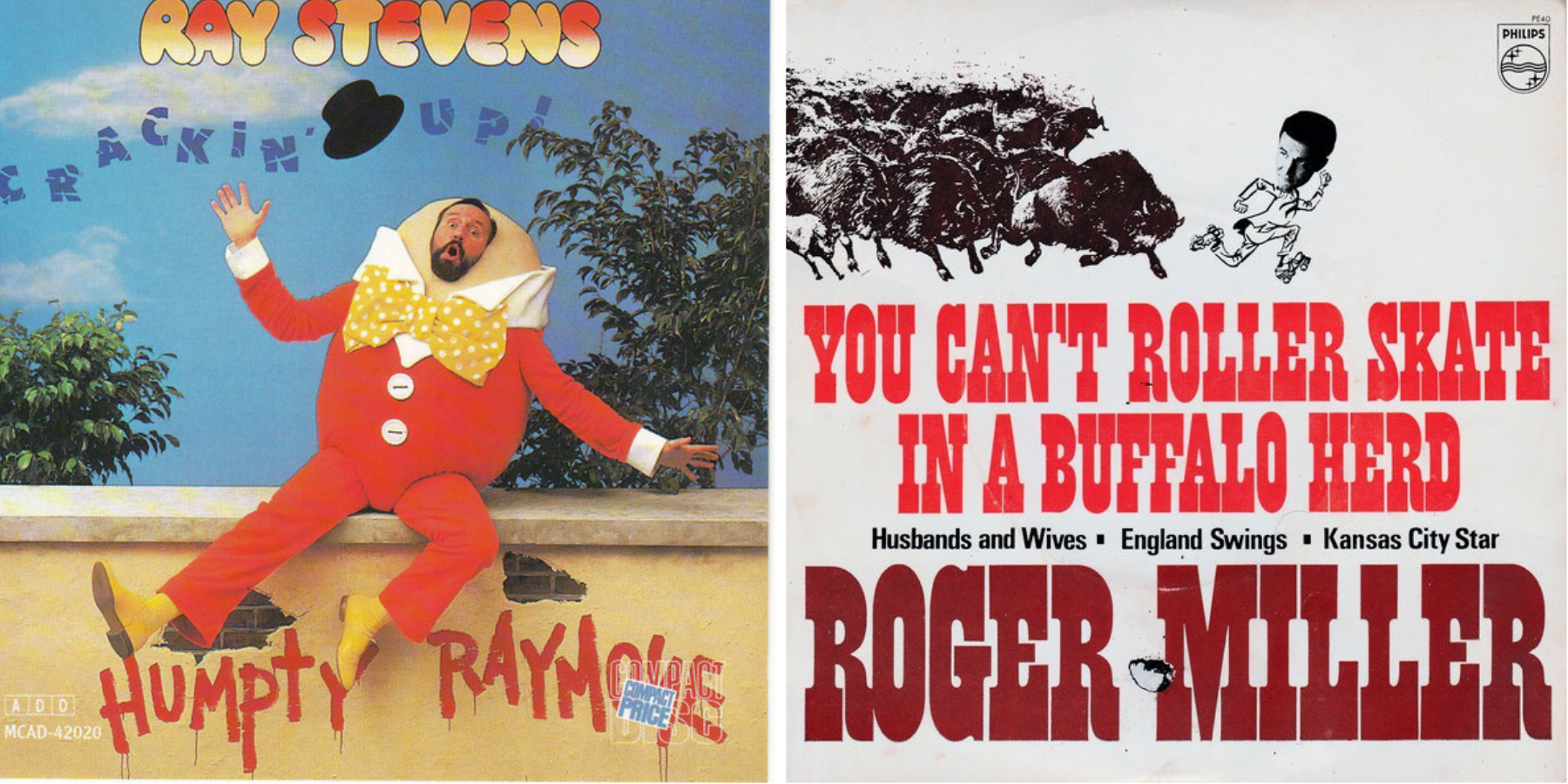

White: When I was growing up, I hated those records. It was not my cup of tea. I was more of a rock ‘n’ roll guy. I was listening to Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin and AC/DC — stuff like that that. When I got to college I started listening to Steve Earle and Rosanne Cash and Emmylou Harris. I realized the reason I was digging those records so much is because of all those country records I grew up with. That’s what they grew up with, too, so we had a common DNA. So, I dug back into all those records that I knew by heart and realized how much I loved them. They influenced my decisions musically all the time whether I knew it or not. I finally just fully embraced it.

Over the last few years, you’ve been drawn to music from the countrypolitan era. Why did you want to tap into that for The Hurting Kind?

I think it was just a huge hole in that part of my discography that I was listening to. I was looking for that stuff everywhere. I’d worn those records out, and I knew them backwards and forwards. I was trying to find something in a modern setting that was doing that thing, because that’s just what I craved and what I wanted to listen to.

I then went out and made the record that I was looking for. I decided, “Well, I’m going to find the guys that wrote a lot of those songs.” So I got to write with Whisperin’ Bill Anderson and Bobby Braddock for this album. I got the seal of approval from them that I was on the right track. That’s huge.

You wanted to capture that countrypolitan aesthetic, but you didn’t want The Hurting Kind to sound retro. How did you achieve that?

I didn’t actively do anything to keep it from sounding retro. I wanted it to sound like a modern record, but with those same sensibilities of the string arrangements, vocal harmonies and that country-jazz Chet Atkins-type guitar style. But I wanted to capture it in the way you capture sounds today and not feel like you have to use all old ribbon mics and old RCA microphones that they were forced to use. We have lots more tools at our disposal. If we had finished this record and were just following our guts and it sounded like an old record, then so be it. But I’m glad it sounds like its own thing.

The aesthetic I was going for was really captured in the songwriting process. I arranged all these songs in my head the way that I thought they should sound, and the way they should progress dynamically, before I ever walked into the studio.

“You Lost Me” is such a great cheating song, and one of the most devastating on an album full of heartbreak songs. How are you so good at writing these sad songs?

I’m not meant to write songs to cheer you up. I’d fail miserably because they don’t move me. They don’t make me feel something. My songs aren’t necessarily sad as much as they’ll stir up an emotion. It might be longing or it might be love, but at an angle. Like, “I love you and you’re so horrible for me.” That’s more interesting to me, ‘cause just the straight up love songs, it’s been done. I come at it from a completely different perspective.

Doomed love is also the topic of “This Isn’t Gonna End Well,” a duet with Lee Ann Womack. Why was she the right fit for that song?

I needed a timeless voice — a voice that could straddle genre, but also, I won’t lie, I wanted a voice that would be recognizable. Lee Ann was every one of those boxes checked. She’s really made strides towards creating true, traditional music and sort of separating herself from the typical Music Row stuff. We’ve known each other for a while and have talked about collaborating and never have. I knew, because of Bobby writing it with me, I could be confident enough to walk in the room and ask her out, as it were. She said yes.

You’re singing with a lot of emotion and vulnerability on this album, which isn’t common for a man to do in 2019. Why is that?

Because it’s ain’t cool, I guess. I love Roy Orbison and Marty Robbins — the guys that just put their heart on their sleeve and are not afraid of the drama and bowl you over with it. They make sure you know exactly what they’re feeling with those big notes and the trills and stuff. I think ever since Nirvana came along, so many wonderful things about that whole movement, but it also became so much shoe-gazing. That’s fine, and I like some of that music, but what I really like is a guy up front with confidence putting it all out there and letting you know exactly how he feels and not giving a shit what you think about it.

It’s not easy to pull that singing style off, either. Your voice has really evolved on this album.

I appreciate you saying that. I think it was a confidence thing, too. I think it was a conscious decision to step forward and be counted and give people what I have and not hold back. Not give them 80 or 90 percent. I honestly feel like I’m singing better now than I ever have. I feel like every time I get in front of a microphone or get onstage or am in the studio, I figure something out. I tweak something that makes it a little less hard, a little more comfortable or easier to project — a little better tone, and that’s exciting.

Being an Alabama native like yourself, I’ve found a lot of meaning in the album’s opening song, “The Good Old Days,” with the news coming out of the Alabama state legislature. You’re now performing that song all across the country and overseas and in some ways representing the state to your audience. I have to say, it’s complicated to be from Alabama these days.

It most certainly is. I get it left and right. I’m proud to be known as an Alabamian. I don’t take that lightly. I don’t tend to want to be the preachy guy around here, because I’ve never gravitated towards those sorts of people anyway. The whole proselytizing thing of, “This is what you should believe and this is what you should not believe” does not sit well with me. But at some point around here, it just gets to a fever pitch to where you can’t keep your mouth shut.

That song was definitely a big middle finger to the idea of “Making America Great Again,” because for most people in this country that aren’t white, straight dudes, it wasn’t great. It hasn’t been great. I’m trying every day to teach my children about tolerance and compassion and making sure they know this country was really, really hard on a lot of people that didn’t fit what people considered the norm.

I don’t ever want to see that shit happen again. I don’t want it on their watch. I want to make sure they’ve got their eyes open and that they change things and don’t ever say we should have it back like it used to be. No. I don’t want that for a minute. I want it like it says in the song, “Our best days are in front of us.” I have to believe in that. There are days when I wonder, but I have to have that hope.

Photo credit: Alysse Gafkjen