Atlanta-based, globally-influenced string band Rising Appalachia bring a unique flavor to American roots music. Drawing on modern styles and traditional sentiments, they craft an original take on folk. Fronted by sisters Leah and Chloe Smith, the band has a sound that is at once familiar and fresh, incorporating various world percussion instruments, reggae-esque grooves, and fluttery melodies that deliver the songs’ meanings with clarity and precision. Like many folk artists before them, Rising Appalachia are no strangers to building art around their activism. One action the band prides itself on is the Slow Music Movement, an idea aimed at creating sustainable practices for touring entertainment acts and re-framing performance as a public service. Watch Rising Appalachia on NPR’s Tiny Desk.

Tag: folk music

Shaun Richardson & Seth Taylor, “Chisholm”

An expansive generation of simply ludicrous flatpickers has rendered bluegrass, old-time, Americana, and folk replete with acoustic guitar virtuosos. Pickers like Jake Stargel, Molly Tuttle, Presley Barker, and Billy Strings each have in common commanding right hands and withering technique. Others, like Jake Workman, Trey Hensley, and Chris Luquette play at incomprehensible, blistering speeds with pristine precision that defies explanation — down to the most infinitesimal note durations. We can clearly see the shredtastic legacies of Clarence White, Tony Rice, Dan Tyminski, and others living on, even if chiefly through their more mathematical, aggressive, and adventurous methods and tones.

That adventurous aggression might just be why “Chisholm,” a new tune composed by guitarists Shaun Richardson and Seth Taylor, feels like such a calming breath of fresh air. It’s a welcome counterpoint and complement to the repeated face-peeling-off that we all enjoy in this current golden age of flatpicking guitar. Richardson and Taylor are both veterans of Dailey & Vincent’s bluegrass-based rootsy stage show, giving them ample experience in musical code-switching, from fiddle tunes and swinging numbers to country ballads and passionate gospel. Richardson has performed with Michael Martin Murphey as well, and Taylor is a member of the long-running, heady, Americana-tinged bluegrass group Mountain Heart.

The versatility lent by these diverse experiences gives “Chisholm” a well-traveled, though relaxed, voluminous vibe. The melodies are resonant and tactile, conjuring six-string players and composers such as John Carlini and Beppe Gambetta — with just a dash of Tommy Emmanuel. Jazz complexities are utilized here not in a gratuitous way, but rather anchored in expressiveness and musical dialogue. Richardson and Taylor’s expertise is very clearly centered not on simply displaying prowess, but in musicality. In this calmer, more subdued setting, that dynamic is especially refreshing and subtly striking.

Photo and video shot by James Shipman

STREAM: Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer, ‘WAHOO!’

Artist: Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer

Hometown: Silver Spring, Maryland

Song: “High on a Mountain”

Album: WAHOO!

Release Date: October 11, 2019

Label: Community Music, Inc.

In Their Words: “The ukulele has as many Americana and roots music voices as the player has, and that’s what we’ve explored on WAHOO! From the Turlough O’Carrolan Irish piece ‘Morgan Megan’ to a bluesy version of Ola Belle Reed’s ‘High on a Mountain,’ we’re pushing the ukulele into places that are new and exciting and love creating unique combinations with uke and cello banjo, uke and guitar, baritone and tenor uke, uke and electric guitar, songwriting and vocals. Somehow, all of our musical worlds come together on this little four string piece of magic.” — Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer

Photo credit: Irene Young

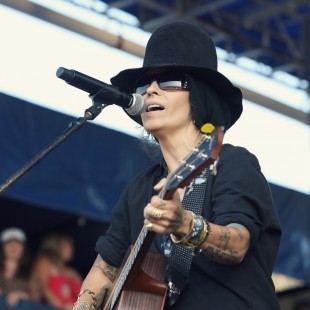

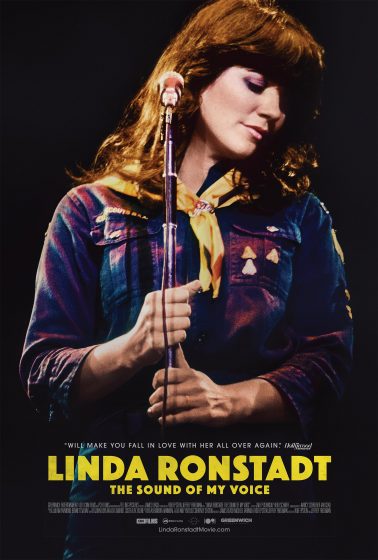

Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass (Part 2 of 2)

In honor of the new documentary film, Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, and in appreciation of her connection to bluegrass — and in an attempt to shout it from the proverbial rooftops! — we’re reprinting Dan Mazer’s 1996 Bluegrass Unlimited interview with Ronstadt split into two parts, but in its entirety on BGS. Special thanks to the team at Bluegrass Unlimited for partnering with BGS to spotlight how bluegrass has touched one of the most important and truly iconic voices to ever grace this planet.

(Read part one of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

“Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass”

By Dan Mazer. Bluegrass Unlimited, June 1996

…Our conversation moved to a discussion of Alison Krauss’ musicianship. Krauss seems to have an incredible variety of influences, which come out when she wants them to. “And in an appropriate manner,” Ronstadt continued. “There seems to be a general agreement among all the people that I know – whose various subjectivities are very strict and very demanding – that Alison has the best taste of any of those people.

“Every fiddle player that I’ve ever worked with will be tempted to play sound(s) like donkeys braying; or just play too much – play ‘flash’ licks in an inappropriate manner. (I call it) ‘The Paganini Syndrome.’ And Alison never is.

“Her pitch is completely stunning! I’m a pitch nazi, and she’s even a little more strict than I am, in terms of pitch. And the thing that I like the very best about her playing is her rhythm. She’s got that great, easy, loping sense of the groove that bluegrass players generally don’t have. When it’s right, of course, it’s got a great swing to it. But bluegrass players have a tendency to get a little stiff and a little on top of the groove. And she never does! I don’t think she’s played with drummers that much, but we put her together with Jim Keltner, and it was just an amazing thing. She’s got the same sense of the groove that he does, and he has the effortless pocket. I consider her as good as any musician I’ve ever worked with. My cousin (David Lindley) said she was his favorite fiddle player ever. And I love her. And also, she owns Maria Callas’ bed! (Laughter) I don’t know why, or how she managed to get her hands on it, but she did. I was jealous. I wanted to be the one to get it. Emmylou Harris and I are both Maria Callas fans. Slobbering, drooling Maria Callas fans!”

When asked to comment on other bluegrass acts, Ronstadt confessed that she doesn’t listen to any modern music of any style. In fact, she was unfamiliar with many of the major country acts. Nor had she ever heard of the IBMA. “Honestly, the only ones I know (are) Ricky Skaggs, Alison, and (the) Seldom Scene,” she said. “But before that, it really was those original guys (Flatt and Scruggs and Monroe). I mean, it was such a short-lived era. And before that, the Blue Sky Boys, which wasn’t really bluegrass, but which really sorta fed right into it. I love those guys, and I listen to the Louvin Brothers a lot. So I listen to all the stuff that led right up to it.

“I know very little of any kind of contemporary music. I just don’t. I listen to NPR, and I listen to Maria Callas and them, and I listen to a lot of Mexican music, and that’s about it. And if it penetrates through that it’s usually because Emmy calls me up, or John Starling calls me up, or Quint Davis. Quint Davis is the guy that runs the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and he put on that thing on the Mall for the inauguration. That’s where I saw Alison. I was just blown away by her!

“I don’t know modern stuff. I haven’t a clue. It seems like when we did the ‘Trio’ record, nobody was interested in traditional music. And then that record was pretty successful, and at that point, Ricky Skaggs was extremely successful, but all of a sudden, I don’t know. I don’t watch this type of stuff on television. I haven’t got the vaguest idea, and I don’t listen to the radio. I have a great respect for anything that anybody does. I mean, I think it’s just so hard to make a record – any record – that I don’t like to put myself in the position of, ‘This is good, and that’s not good,’ like a bean-counter. But I have to say that (modern country fails) to capture my interest.

“There’s always music in front of my face. If I was gonna sit and listen to Mozart, (and) someone said, ‘OK, this is gonna be it (you can only listen to Mozart) forever,’ I’d go, ‘OK.’ And if someone was playing me some Mexican traditional music, and they said, ‘This is gonna be it forever,’ I’d go, ‘OK.’ Because there’s enough in any of those things, to (keep me interested).

“Somebody came over to my house the other day with some musicians from Madagascar. They sit down in my kitchen and played this Malagassi music, and it just blew me through the wall! So, if they had said at that point, ‘Well, you’re gonna have to sing a little Malagassi now,’ I would’ve said, ‘Well, OK. Fine!’ I could’ve got right down and sung with them, and had no problem at all. But I can only concentrate on one thing at a time, and if that thin is interesting, I just don’t have any particular need to shift my attention.

“When John Starling comes out to visit me, he sits down at my kitchen table with his guitar, and we start singing. I get pried back to English. But I’d really rather sing in Spanish or Italian. Because all that stuff (bluegrass and country) is based on rural southern pronunciation. And in Spanish – if I’m singing a Latin jazz thing that’s a Caribbean base, I have to push myself from my northern Mexican rural accent into a Caribbean accent, which is painful for me. I find it an unpleasant way to pronounce the language, but I have to do it in order to get the rhythms right. So I do it. I really push myself into that other accent. But I prefer singing in my own accent – the accent of my family’s region. I can just get so much more sound out of my voice in that language.”

Over the course of a career, an artist makes many decisions based upon the age-old dilemma of commercialism versus artistic merit. What the public wants to buy is not always what the artists likes [sic] to paint, play, or sing. Ms. Ronstadt has lately recorded opera, Big Band and Mexican music, none of which usually sells platinum in today’s market. It seems that she has reached a point in which she doesn’t have to worry about selling a certain number of records; her musical decisions are now totally artistic. “Well, they were to start with, too. It’s just that I wasn’t as good at executing them!” She protested with a laugh. “And I find that now. I’m making my choices based on an artistic thing, but I am also finding that my choices were made for me when I was a baby. It’s getting harder, though. I do find that the record companies have a tendency to stick their oar in a lot more now. It’s very nervous-making. Although, the one person that I’ve allowed to submit material and give advice – I don’t always take it, but I always consider it – is (Asylum Records President) Kyle Lehning. He’s an amazing guy! He really, genuinely likes music, first of all, which is rare for a record person. Second of all, he’s extremely knowledgeable, and he has great taste in songs. And he seems dedicated to the idea of trying to save what he can that’s quality, and nurture it.

“(The latest project) started with several nagging phone calls from John Starling!” She laughed. “John Starling doesn’t get down behind traditional Mexican music! And then Emmy calling me, because Emmy and I are such fans of the McGarrigle Sisters. We were talking about doing some television stuff. We were just trying to think of how we could get in the living room together again with John Starling. So we started working on tunes, like the Carter Family songs that only Emmy and I would be interested in. And maybe John Starling or Claire Lynch, or somebody. John had, a long time ago, sent us Claire Lynch records, saying, ‘You really gotta sing with this girl. She’s real wonderful.’ So claire and Emmy and I have done some stuff together.

“And then, I’ve been working with Valerie Carter. She put a record out in the ‘70s. Everybody in Hollywood was after her. She’s an extraordinary singer, and she was exceptionally beautiful. She was about 19, I think, then. Lowell George and Mick Jagger and Jackson Browne and J.D. Souther and Danny Kortchmar – everybody wanted to work with her. Everybody tried to, and then George Massenberg, who is my production partner – who I met through John Starling – did produce a record from her, and so did Lowell George. I sang on it. Then she just had some problems, and she dropped out of sight for about 15 years, which was really a tragedy for us. ‘Cause she’s one of those girls that can sing as well as Whitney Houston. She’s got that kind of chops. But it doesn’t sound like her. It’s a very distinctive voice. But that kind of ability. It was too bad, ‘cause she was (a) really interesting singer. So she’s now been singing on the road with James Taylor a lot. I used her to sing a lot on my last record, that I put out. The blend between her and me and Emmy was just really magical! So we’ve done some stuff together, the three of us.

“But what Emmy and I wanted to do was just explore. See what we could go find out there. We wanted to push the limits a little bit, and see what we could find in terms of texture, combining styles, of things that we liked that don’t always fit in one little (category). Like the McGarrigle Sisters. Where do you put that? It’s not really traditional folk music, and it’s got traditional roots. It certainly isn’t bluegrass. And the sentiment is too unbridled for current pop, ‘cool’ standards. But it’s very intelligent music.

“There’s other stuff that is kind of like that; that’s kind of ‘out there.’ And there’s some stuff that’s just real, real traditional. So we’ve just been fooling around with various singers. And then I sang with Claire Lynch and my cousin John, who’s got a wonderful voice – on two songs.”

Although she maintains that after a project is finished she doesn’t care what happens, Ronstadt is intensely involved in its creation. “Oh, I mix everything! I do every single thing,” she declared. “I make the record, I do the arrangements, I do the harmony arrangements, I do a lot of the instrumental arrangements. Nothing is done on the record without me being there. But when it’s finished, I never listen to it again. You can take it and throw it off a cliff, for all I care. I’ve heard it and I’ve done it, and that’s the experience; and now I go on to something else. So at that point, I surrender it to the record company, and they do whatever. They can shoot it with a gun if they want to. I don’t care what they do. Long as they don’t shoot me.”

Returning to the topic of bluegrass, Ronstadt commented, “I understand what [the banjo] does, rhythmically. And I appreciate what it does – that syncopated thing; the difference in all those accents.

“I think of the banjo kinda like I think of the trumpet in mariachi, which is: trumpet was brought in about the same time that the resonator was added onto the back of the banjo. It was a ‘radio’ event, and a good one. It was a really good thing; it needed that high end to cut through. But if somebody came to bed and blew a trumpet in my ear, I’d get annoyed! If somebody came to bed with me and started plucking a banjo, I would probably jump right up to the ceiling! But it’s a great instrument in the orchestral blend. It’s really got a great place. And I don’t think the banjo will ever go out of style.

“Those other instruments are a lot more flexible. They can bear a lot more. I’ve really become a complete mandolin fan, ‘cause I’ve been working with David Grisman. I just think he’s a genius. I knew his playing. I knew he was considered a ‘hot chops’ player. I think he plays bluegrass sometimes, but he really predates and transcends all of that stuff completely. I mean, he can play like a classical player. I’ve never heard anybody with dynamics like that, and I’ve never played with anybody that could play with a vocalist; and play little internal harmonies. He just flits around like a little hummingbird – all around the vocal line – and plays a beautiful little harmony for a while, and then he goes off to a rhythm pattern, then he comes back. He has great ideas for voicings, and he has very, very good rhythm ideas. I just love to work with him. I think he’s brilliant.

“You know what I think is missing from bluegrass at this point? And from all that kind of traditional music? Dancing. That’s what I discovered with Mexican music, was that it is dance music. Period. I think, as is fiddle (music). As soon as you uncouple it from (dancing), the music changes. It’s the same way with pop music. As soon as it became recorded music – people started dancing in discos to recorded music – the music stopped being alive, and it stopped changing in a real vital way. Started changing in a more static, strange, mechanized way.

“So my suggestion, to the bluegrass world would be, one should never uncouple that music from dancing. There should always be dancers involved with bluegrass music.”

The author commented that singing is also something that’s been taken away from most people and given only to professionals. “Yeah, it’s an outrage! In Mexican culture, everyone sings,” she responded. “Everyone knows all the words, and they all sing. We sing at the dinner table. Whatever you’re doing, you sing. You sing in a funeral, you sing at a birthday, you sing at a wedding. You sing if you’re happy, you sing if you’re sad. It’s a thing you get to do to help you along with your life. Everyone should sing. It’s a biological necessity. Even little babies sing. I mean, even when they’re pre-verbal, you hear them kind of leaning into a sound.”

(Read part one of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

Photos and artwork courtesy of Shore Fire Media

Article appears courtesy of Bluegrass Unlimited

Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass (Part 1 of 2)

Barely three minutes into the brand new documentary, Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, the viewer is already presented with none other than Dolly Parton, who exclaims, “Linda could literally sing anything.”

Over the course of her singular, era-defining career Ronstadt did sing almost anything — from The Pirates of Penzance to American standards to Mexican folk songs — but she’s rarely referenced in the same breath as bluegrass. The BGS x Linda Ronstadt history notwithstanding, it’s understanding that the twain rarely meet, in conversation and consideration. Of her most easily recognizable hits, among them “Willin’,” “You’re No Good,” and “Desperado,” perhaps “Blue Bayou” is the closest to bluegrass — and in its Ronstadt iteration, less so than in other covers of the languid ballad.

Scratch the surface, though, no matter how slightly, and her bluegrass cred runs deep. This should come as no surprise, given her immaculate performances alongside Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris on Trio and Trio II — the first song the three sang together, informally, at Harris’s house in L.A. was “Bury Me Beneath the Willow.” The Sound of My Voice digs a little deeper still, reminding that Ronstadt’s very first hit, “Different Drum,” recorded with folk-rock trio the Stone Poneys, was discovered by Ronstadt, who first heard the song from a now almost-forgotten bluegrass band, the Greenbriar Boys.

Elsewhere in the film, Ronstadt mentions that during her early days in the city she frequented Los Angeles’ The Ash Grove, the foremost folk and bluegrass venue there in the ‘60s and ‘70s. She also made appearances and recorded with the Seldom Scene, and remained close friends and musical confidantes with John Starling. One of the last studio recordings Ronstadt ever released was a duet of the Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard classic, “Pretty Bird” with bluegrass legend Laurie Lewis. The track was released on Ronstadt’s Duets project as well as Lewis’s The Hazel and Alice Sessions and the pair worked together prior, as well, performing as “The Bluebirds” with Maria Muldaur at Wintergrass Music Festival in 2005.

The bluegrass tendrils are there, undeniably, woven alongside so many other influences and inspirations and impressions that informed Ronstadt’s art. Still, it was surprising to this writer to find that in June 1996 Bluegrass Unlimited, the foremost and longest-running print publication dedicated solely to bluegrass music, had featured a lengthy, in-depth interview with Linda Ronstadt herself. Even by author Dan Mazer’s own admission, “Ms. Ronstadt’s bluegrass/country connection is tenuous at best.” And yet, for nearly five thousand words, the article displays that Ronstadt isn’t just tangentially connected to bluegrass, it is a permanent part of her musical self.

In honor of the new documentary film, and in appreciation of this connection to bluegrass — and in an attempt to shout it from the proverbial rooftops! — we’re reprinting Dan Mazer’s interview with Ronstadt exactly how it appeared in 1996, split into two parts, but in its entirety on BGS. Special thanks to the team at Bluegrass Unlimited for partnering with BGS to spotlight how bluegrass has touched one of the most important and truly iconic voices to ever grace this planet. — Justin Hiltner, BGS Associate Editor

(Read part two of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

“Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass”

By Dan Mazer. Bluegrass Unlimited, June 1996

While preparing an article on the influence of bluegrass on today’s country music, I had the opportunity to interview several prominent country stars. During discussions with Bluegrass Unlimited’s editorial staff about artists to interview, the name Linda Ronstadt came up.

Linda Ronstadt? It seemed an odd choice at first. Ms. Ronstadt has had a long and varied career, and while her forays into bluegrass with the Seldom Scene have been recognized and celebrated within the bluegrass community, as an artist, she just didn’t seem to fit in with the likes of Marty Stuart, Hal Ketchum, and Patty Loveless. On the other hand, her classic recordings of “Blue Bayou,” “Silver Threads and Golden Needles” and “When Will I Be Loved?” are still copied by country music cover bands some 20 years after their release. Some of her work as also been covered by bluegrass artists.

Because Ms. Ronstadt’s bluegrass/country connection is tenuous at best (especially in recent years, when her recordings have featured opera, Big Band and Mexican music), it was with little hope that I sent an interview request to Ms. Ronstadt’s publicist. To my surprise and delight, the request as answered quickly with a call from the publicist to set an appointment for a telephone interview. Ms. Ronstadt called me from her home in Los Angeles, and graciously granted me a significantly longer interview than we had arranged – that was just because the conversation was so interesting and enjoyable! She is remarkably well-spoken, intelligent and passionate. In the end, we decided not to include Ms. Ronstadt’s remarks in the profile of country artists with bluegrass roots.

Ms. Ronstadt grew up in Tuscon, Ariz. Her family listened to a broad variety of music on the radio. Opera, country, rock ‘n’ roll, and jazz filled the house. Some radio shows also featured bluegrass. “We were right in the pat of XERF, Del Rio, Tex,” she said. “And we (had) the Louisiana Hayride. We were right there, where there was a lot of big transmitters, and not a lot of interference. So I heard (bluegrass) when I was little, growing up.

“When we were kids just listening to stuff on the radio, we tried to sing it. My brother and sister and I could always harmonize real early. So we used to sing the stuff we heard on the radio. We heard Bill Monroe, and we heard Flatt and Scruggs, we heard Homer and Jethro doing a sendup of ‘Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes.’ I had such a cross-section! And then, when I was in high school, I think it really intensified.

“I’ve always been interested in harmony. I’ve always been a harmony singer. When I was a real little child, I could sing harmony. I’m always surprised when children say, when they’re three, that they can’t. But all my brothers and sisters could, real early. I could hear strange harmonies, too. But I understood Mexican harmonies better, and they have a tendency to be very, very clear kind of parallel thirds.”

(Author’s Note: “Parallel thirds” refers to what, in bluegrass, corresponds to the lead and tenor part singing close harmony at the interval called a “third.” Brother duets also feature this harmony.)

As an artist, Ronstadt doesn’t feel authentically connected to bluegrass. “I feel that I would have had to live in the rural south, and grow up in the mountains,” she said. “There’s just such a difference between mountain South and plantation South. Culturally and musically.”

Since she grew up near the Mexican border, and her father is Mexican, Ronstadt mostly sang Mexican music as a child. “There’s a great deal of similarities (between bluegrass and Mexican music),” she noted. “One of them is that the three-part harmony stuff that we sang a lot is Mexican mountain music, and it’s country music. The music of an agrarian lifestyle is what I’ve always been most attracted to. I love it, and having grown up in a kind of isolated, rural setting, it was something that reflected what I was witnessing around me.

“I’ve always had an ear for any kind of a thrilling, wild, high tenor. And again, in Mexican music, there’s a loose parallel, especially up in the mountains, where they sing real high in this falsetto, in the huapango style.

“The language and the pronunciation of the language – whatever the rural accent is – influences the style of singing and the vocal intonation so profoundly! With bluegrass music it was those ways of pronouncing 16th Century English, probably, frozen in those mountains. But in Mexico, of course, it was the indigenous language of nahuatl, which was what was mostly spoken there, which gave the pronunciation and forced the tonality into that nasal thing.

“Also, having to communicate across long distances, you get a real high, ringing (tone). Men get a lot of power out of that high register; way more than women do, which is why – having absolutely nothing to do with sexism –I feel that bluegrass is very wonderful when it’s three male voices. Mariachi music, also (is an example), which is from a different region (Jalisco). But when all those male voices are singing up in the high register, it’s a different sound from a woman’s voice singing up in a more comfortable register. I can sing bluegrass tenor pretty well, but it doesn’t quite have the power that it will ever have from a man forcing himself up way high in that register. It just doesn’t have the same dynamic. It’s still good. I call it ‘pink grass.’”

Until recently, bluegrass has been almost entirely a male reserve. Ronstadt feels that there is good reason for that, although, as she pointed out, “There was old-time music before that, which of course, happily embraced women singers. But I still think it was just that thrilling sound of those male voices in two- and three-part harmony, pushed way, way up high, that really gave it a very distinctive characteristic. And it’s pretty hard to compromise that, regardless of your sexual politics, without making it into something different.

“There are women singers today that have what I think (are) very, very good, and very authentic-sounding bluegrass voices. I think Claire Lynch has a wonderful voice. I love her singing! And those girls that sing with Alison Krauss; the Cox Family. But it’s hard to say. Where do you draw the line? Is that bluegrass, or is that old-time? I think that’s a combination; both things.”

When thinking of acts that embrace and also expand bluegrass, the Seldom Scene immediately comes to mind. Many people argue with some justification that the inclusion of a banjo defines an act as a bluegrass band. Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, Reno and Smiley and the Stanley Brothers all performed certain songs (usually gospel numbers) without the banjo, but the Seldom Scene broke new ground with their unprecedented, mellow guitar-based sound. Furthermore, because Ben Eldridge’s banjo playing is unparalleled for taste and restraint, the Seldom Scene can be mellow even on tunes that include the banjo. They also distinguished themselves by using Linda Ronstadt as a backup vocalist on some of their earlier recordings. They remain her favorite bluegrass band.

“They really are an urban band with very, very strong rural influences,” she said. “They had all the benefit of a sophisticated, cosmopolitan atmosphere, which Washington, D.C., certainly is, and they were able to refine in any direction they wanted to. I really think they made an extraordinary synthesis. I love that band; I always have.

“Mike (Auldridge) is such a unique player. Nobody sounds like him. He’s got that real beautiful, lyrical, velvet thing that happens, but it’s still got plenty of strength and guts behind it. There are more famous Dobro [resonator guitar] players than that, but I like him the best and I always call him when I want a Dobro [resonator guitar] player.

“John Starling is an exceptional singer, and has a wonderful sense of the groove. He’s a very, very fine guitar player. Emmylou Harris and I both spent so many hours and hours and nights and nights and months and months with him, way on into the night, just grooving on that sound and exploring it! He’s given us a wealth of something. It’s hard to define. But just having that superb musicianship to lean on, and the focus of his sensibility, which is very keen and very well-developed in that direction.

“I remember getting snowed in at John Starling’s house with Lowell George, and Emmy, and Ricky Skaggs (in 1974 or 1975). Fayssoux Starling was there, who was a good singer. And we sang forever! I mean, we sang all night, and they were there for three days. I was sick, so i was there for a month, they were there for three days, and in that time, Ricky Skaggs taught me a whole lot about how to sing bluegrass harmony. I knew a little bit about it, but he really showed me how the suspensions worked, and it helped me to refine it a lot. I understood (the suspensions), but didn’t know quite how to really imply them. He Walked me through ‘em, and after that, I had ‘em.”

(Author’s Note: “Suspensions” is a musical term referring to creating tension in a chord by sounding a not that is not in the chord, and then releasing that tension by lowering the dissonant note. For example, a guitarist will sometimes play a “D” chord and add a high “G” note on the third fret of the first string for one measure, then release that fret, so that the “F#” note rings.)

Ronstadt is surprised that she is sometimes cited within country music. “I was never a country singer,” she stated. “I never thought of myself as a country singer. Always very surprised if anybody else did. I was a pop music singer, and I used various root forms that were acceptable to me, and that was one of the things that was readily acceptable to me.

“I’ve always had a little rule about my singing. If it wasn’t there in the living room by the time I was eight years old, it generally won’t be very successful if I take a swing at it, at least to my standards. But thanks to the radio, there was a lot of stuff in play by the time I was eight. And thanks to the fact that my family has very eclectic kind of taste, anyway.

“So, when I came into pop music, I played songs that I loved. I didn’t care whether they were written by George Gershwin or Hank Williams. A song that would really inspire me for one reason or another, I’d try to sing it. And I’d always try to put it into its appropriate setting. So if it (was) a bluegrass song, I’d try to put it in that kind of setting, and I knew enough about the mechanics of how it worked, so that I would do that. Then there were these singers and players that I really admired, and tried to emulate. But that thrilling high tenor sound, there’s just nothing like it.”

The closest Ronstadt has come to recording bluegrass in recent years was on the “Trio” album, which featured her along with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris. A follow-up recording was eagerly anticipated, but never materialized. “The ‘Trio’ record became so difficult, schedule-wise, that we all gave up,” she said. “But Emmy and I did quite a lot of singing together. We had a great time! See, Emmy and I started out with this idea to do a record together, where we would use some guest artists. And we sort of progressed down that road, but it never got to where everybody would agree on a release date. Everybody did agree at some point, but the people kept changin’ their minds.

“But Emmy and I really are kind of locked on to each other musically. Emmy and I have sung some stuff together that’s gonna be on my record; Emmy and I have sung some stuff together that’s gonna be on her record. And we also did some stuff with Valerie Carter, who’s just a great singer.”

Ronstadt’s bluegrass influence is definitely shown in her current release.

(Read part two of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

Photos courtesy of Shore Fire Media

Article appears courtesy of Bluegrass Unlimited

WATCH: Rhiannon Giddens Plays the Tiny Desk

Former Carolina Chocolate Drops leader and old-time music maven Rhiannon Giddens has the uncanny ability to sing through an audience. In May, she released her third full-length, studio album, there is no Other, with Nonesuch Records. In this new chapter, Giddens collaborated with Italian multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi, who is known for his virtuosity on percussion and jazz piano. Giddens, Turrisi, and bassist Jason Sypher stopped by NPR to perform some music from the latest record; watch as they stun the audience huddled around the Tiny Desk.

Photo credit: Claire Harbage/NPR

The Show On The Road – Matt the Electrician

This week, Matt the Electrician — a kind-hearted songwriter and cunning craftsman of smile-inducing folk songs that retain the one thing we might need most in our jackknifed new century: hope.

LISTEN: APPLE PODCASTS • MP3

While the artist not known as Matt Sever may still be able to fix the sparking wires behind your walls with his nimble bear hands, he found a line of work even more daring, dangerous, and financially precarious. What did he set his sights on back in the 1990s? Being a roving folk singer.

Matt’s been at this a while, he looks more like your cool tatted shop teacher than the next big arena money maker for the major labels. So, letting the people who have put him up in their houses and cooked him a warm meal on the road support the music their own way? It’s kind of beautiful. In fact, his sturdy fanbase just lovingly funded his next record, for which he’ll be working with a producer for the very first time, and that producer is none other than Tucker Martine. He’ll be heading up to Tucker’s studio in Portland, Oregon to start the project in October.

Be Together: Newport Folk Fest 2019 in Photographs

Newport Folk Festival has always played host to singular, incomparable, once-in-a-lifetime musical moments. As you read this you can almost certainly think of at least a handful of examples, right off the top of your head. This year carried on that tradition and then some, displaying absolute magic across the festival’s four stages over the course of the weekend. Too many headline-worthy moments were sprinkled throughout, but BGS photographer Daniel Jackson was on hand to capture this folk and roots lightning in a bottle — from the performance debut of super supergroup The Highwomen to celebrating 80 years of Mavis Staples to surprise guests that make being green and looking cheap seem easy and effortless.

Perhaps the most meaningful take away from the festival, though, was not its star-studded stages, but its mantra — a timely reminder in this particular global moment: Be present. Be kind. Be open. Be together. Folk music, in all of its forms, carves out just such a space to allow for this togetherness. See it for yourself in these photographs from Newport Folk Fest 2019.

All photos: Daniel Jackson

ARTIST OF THE MONTH: Pete Seeger

Beyond the significance of May 2019 being BGS Artist of the Month Pete Seeger’s 100th birthday month, this is a chance to recognize that Pete is an artist for every month. His gentle cantor, amiable smile, expertise on both banjo and guitar, rattling voice, respect for the music of the past while making it relevant for the present, political awareness, and constant fight for social justice make him a man for all seasons.

All month long, BGS will be celebrating Pete’s legacy — a legacy that lingers years after his passing. To kick things off, here’s our all-encompassing playlist of the Essential Pete Seeger to get you up to speed. And if you want to dig deeper, check out Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection, which includes a 200-page book with essays, commentary, photographs, and liner notes, along with six CDs of classic and unreleased music.

Illustration: Zachary Johnson

LISTEN: Kieran Kane & Rayna Gellert, “Ain’t Got Jesus”

Artist: Kieran Kane & Rayna Gellert

Hometown: Kane – Queens, New York | Gellert – Elkhart, Indiana

Song: “Ain’t Got Jesus”

Album: When The Sun Goes Down

Release Date: March 20, 2019

Label: Dead Reckoning Records

In Their Words “This song began with Kieran noodling around on the octave mandolin. I loved the riff he was playing, so I picked up the guitar and started playing along. The seeds of the lyrics came from the world of old-time music — Leake County Revelers, Fiddlin’ John Carson, and others — but, in true ‘folk process’ fashion, we sewed them together with modern references. And, as so often happens when writing songs, the initial direction of the song fractured into multiple layers of meaning. We recently had someone at a show holler, ‘What is that song about?’ While it’s tempting to launch into an explanation of intent, it’s more fun to let people hear what they hear.” — Rayna Gellert

Photo credit: Lucas Kane