Christone “Kingfish” Ingram seemed to come out of nowhere with his 2019 Alligator Records debut Kingfish. At 20 years old, the native of Clarksdale, Mississippi, emerged as a fully-formed guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter and was quickly hailed as a defining blues voice of his generation. Since then, he’s toured the nation, performed with acts ranging from alt-rockers Vampire Weekend to Americana star Jason Isbell to blues godfather Buddy Guy.

In the midst of all this success, just as his career was taking off amidst over a year of non-stop touring, he lost his mother, Princess Pride Ingram, a devastating blow that the young man had to overcome.

“She was the biggest supporter that I had,” says Ingram, who is now 22. “She took care of all my business and she didn’t mess around about her baby. She was everything: she was the bodyguard, the manager, the handler. She christened the people who she wanted me to look after me, a few people who had already taken me on as their own, so she knew we were gonna be all right.”

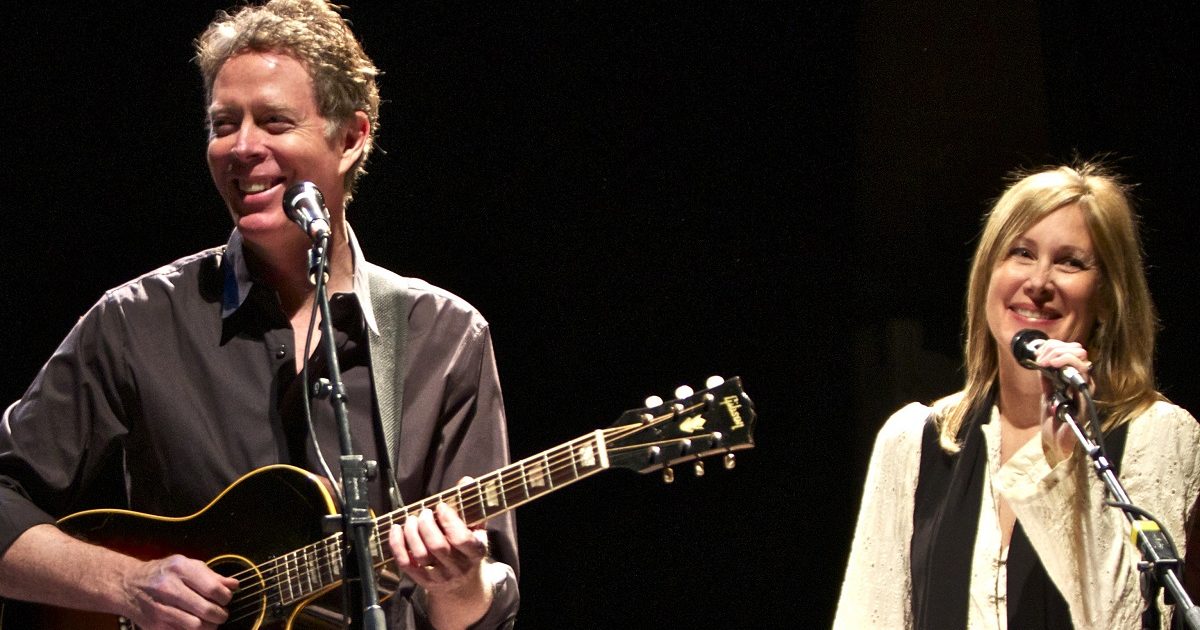

All of this life experience is reflected on Ingram’s second album, 662, named after the area code for his North Mississippi home. Like his debut, 662 was co-written and co-produced by Tom Hambridge, who also collaborates with Buddy Guy. The joint connection is no coincidence.

“I met Tom in 2017 through Mr. Buddy Guy,” says Ingram. “Mr. Guy is the one who fronted the first record and he put us with Tom. Our first writing session together went so smoothly that we got six songs done that day. It was very cool. He’ll spend time listening to the stories that I tell him and we will put our heads together on a groove. We basically bounce ideas off each other until we have a song. The main thing is we’re trying to tell my story.”

Ingram’s story shines through on 662 songs like “Rock and Roll,” which directly addresses his mother’s passing. He says that transferring his emotions into a song was a key part of his grieving process.

“It definitely helped because music has always been my out,” he says. “I never had been a big talker, but I’ve always been able to get my fears and thoughts out through music. There are times when music doesn’t work and tears just have to fall, but most of the time, music is how I get it out. It was a big relief for me. Big time relief.”

Ingram’s personal story about growing up in the Delta, home of the blues, and picking up the torch is also told explicitly in the song “Too Young to Remember,” where the chorus states “I’m too young to remember, but I’m old enough to know.” The song also includes the evocative line, “When you see me play my guitar, you’re looking back 100 years.”

“That’s me representing all the greats that I studied,” says Ingram. “Lightnin’ Hopkins, Son House, Johnny Shines, Robert Nighthawk, Albert King, Otis Rush, B.B. King, Buddy Guy… all those guys that I soaked up, including stuff I’ve gotten from my local blues players. All of that represents way more than 100 years of our history and tradition — maybe 300 years — and it’s important to me.”

Ingram was first exposed to the blues by his father, who showed him a Muddy Waters documentary that drew him in, and then showed him B.B. King’s cameo appearance on Sanford and Son, an underrated moment in the history of the blues. Young Christone was also inspired by the blues band that lived next door to him. But what really turned Ingram from a passive fan of the blues into an active participant was his enrollment in a music education program at the Delta Blues Museum.

“That was the foundation for me,” he says. “When I went there, not only did they teach me how to play but I got a chance to understand more about the blues, where it came from and the history of great blues men and women, many of whom were from the same part of the world as me. Not only did we study songs and instruments and whatnot, but they had these file cabinets they would open up and take out files where we’d read blues stories and have conversations about them. It was a full-on arts education program, a very important part of my development. Before the Blues Museum I sort of knew about the history but I didn’t know it was that important.”

Kingfish focused mostly on hard-driving blues shuffles, though it also included a wider range of material: “Listen,” a gorgeous, upbeat, melodic duet with Keb’ Mo’; “Been Here Before,” an acoustic deep blues that explored his own outsider status as a kid digging an ancient musical form; and a couple of aching slow ballads, highlighted by “That’s Fine By Me.”

662 continues to dig deeper into a wider range of material. “That’s All It Takes” is a beautiful ballad punctuated by surging horn charts and Ingram’s sweet guitar fills framing his aching vocal. “Rock and Roll” and “You’re Already Gone” feature gentle, nuanced singing and swinging, non-blues-based acoustic picking. Indeed, while Hopkins, House, and Shines are the acoustic blues players that Ingram says were his primary influences, they’re not the first unplugged players who come out of his mouth when asked who’s currently inspiring him the most. That would be Tommy Emmanuel and Monte Montgomery, two virtuosos conversant with the blues, but certainly not wedded to the genre.

Ingram considers his acoustic playing essential to his music, featured on stage every night, with him playing duets with the keyboardist. “I love playing acoustic and switching up the dynamics,” he says. “I like to bring the energy up real high and then bring it down.”

As rooted as Ingram is in the roots of the blues, he has also been a proponent of bringing the music into the future, collaborating with peers and with hip hop musicians. Even before his first album was released, he recorded two songs for the streaming series Luke Cage with hip hop artist Rakim, with whom he performed on NPR’s Tiny Desk Concerts.

“I always wanted to do something with blues and hip hop, because hip hop is like the blues’ grandchild,” he says. “We have something like that planned down the road that I can’t discuss yet but I’m really excited about. Working with Rakim was the foundation of me wanting to play real instruments behind rappers. That’s a really great path.”

Working with older musicians from Rakim to Guy also allowed Ingram to observe how to be more professional. When he first started, he was playing covers and took pride in not making setlists, instead just following his instincts.

“In order to have a structured show, you have to have a setlist, so I started to make them and to really work on arrangements instead of just playing,” he says. “All of that worked and then playing all these shows, now I feel like I have more confidence up there. I still get nervous but I have confidence behind it.”

Part of Ingram’s growing confidence is due to simple maturity. Part is due to the reaction of fellow musicians. And part is just watching the crowd and seeing their enthusiastic response. As his touring has grown ever wider, his crowds ever larger, positive reinforcement is the natural consequence of seeing positive response.

“In that moment it really does give me more confidence to see the crowd enjoying it,” he says. “It gives me a sigh of relief and makes me say, ‘Maybe what I’m doing is all right. Somebody likes it.”

Photo credit: Justin Hardiman