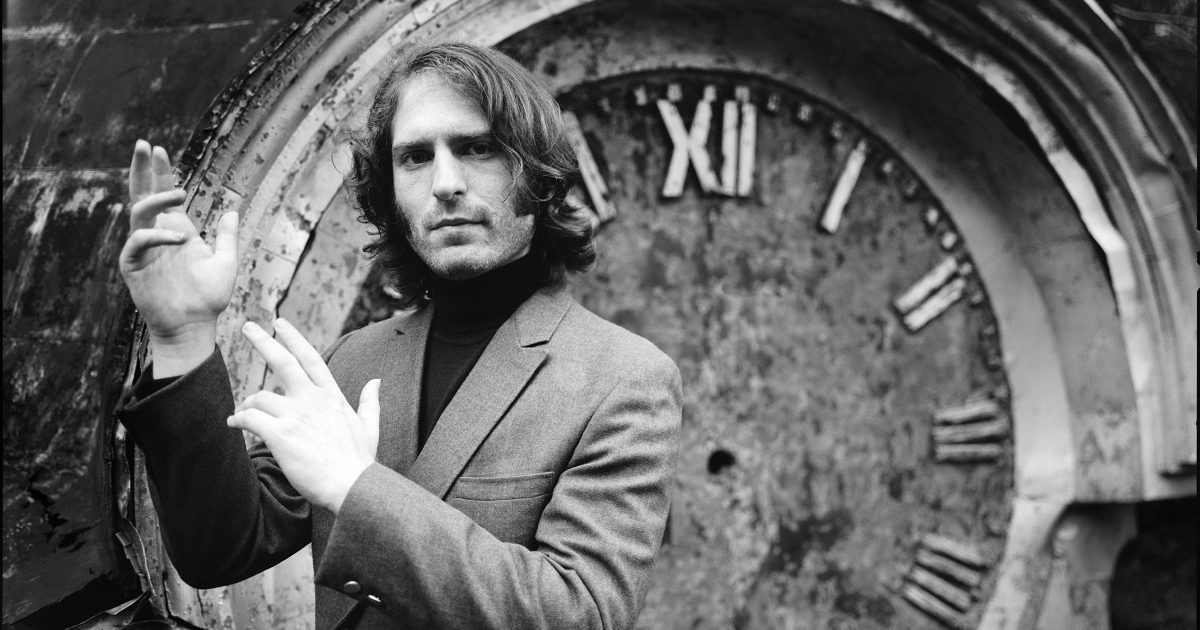

When I was a kid I was obsessed with music. From as far back as I have memories I loved every aspect of it. However, it wasn’t until I started watching older movies and TV shows and becoming educated that I became aware of music as a historical record. Shows like The Wonder Years and Forrest Gump (and others) made me realize that music was telling me a story of what had happened in the past and how we could learn from it. As much as I wanted to be a musician to heal people individually from their darkness, I also wanted to become a musician to inspire large-scale change like my heroes Nina Simone, Pete Seeger, Ani DiFranco and other countless heroes that used their voice to echo what many musicians have been saying since the dawn of human connection I assume.

Here are some of my favorite songs in that vein. — John Craigie

Nina Simone – “The Backlash Blues”

I seriously could have picked any one of her amazing performances, but this one always stood out to me. So direct and in your face. So powerful and moving. It put so much in perspective for my young ears and mind.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono – “Power to the People”

I was always a serious Beatles fan as a kid, but it took me a while to discover John’s solo work outside of “Imagine” and “Instant Karma!” As soon as I got interested in protest music I kept finding such great songs from him and this one has always been a favorite.

Curtis Mayfield – “Move on Up”

When I was in my first band in college I got interested in Curtis Mayfield after hearing the whole album Superfly and falling in love with the bass lines. Taken from his debut album as a solo artist after the Impressions, I’ve included the single version for easy digestion. However, if you can’t get enough I suggest checking out the nine-minute album version.

Buffalo Springfield – “For What It’s Worth”

Most people know this song as the beautiful anthem that it is, and surely still stands the test of time. However, a lot of people forget that this is Stephen Stills and Neil Young before they were in CSNY. I always loved the peaceful and soothing nature of the guitars and harmonics while the lyrics spoke of what was happening all around and begging us to not ignore it.

Richie Havens – “Freedom (Live)”

Legend has it that this song was created on the spot at the Woodstock festival in August of 1969. Richie was slated to go first, and since the promoters weren’t ready with the second band (not to mention many other things) they kept making him go back out after he had finished his set. After several encores he didn’t know what to play so he freestyled this beautiful song. You can feel everything that is going on in the state of the world through his passionate delivery of these simple lyrics.

Bob Dylan – “The Times They Are A-Changin’”

I admit it does feel a bit cliché to add this to the mix but I’ve always felt it was a huge inspiration to me and catalyst for my songwriting. Embarrassingly enough, I first heard this on The Wonder Years when I was about 11 years old. I had no idea what it was but I felt like it had been written that day for exactly what I was going through and seeing in my community of Los Angeles at that time. When I got a guitar a few years later, it was one of the first songs I wanted to learn.

Marvin Gaye – “What’s Going On”

Like most people, I associated Marvin Gaye early on as smooth, sexy date music. Something to put on in the dorm room when your girlfriend was coming by. But I remember getting a little pamphlet from my local record store of “essential landmark albums.” Having never heard of What’s Going On but trusting Marvin I got that album and it has been a favorite ever since. This is the first track on side 1 and it says everything about injustice so beautifully.

Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young – “Ohio”

I’ve read that Neil heard about the Kent State shootings and was so emotionally affected that he wrote this song immediately and soon after they went in the studio to record it. The shootings happened on May 4, 1970 and the single was out just a couple weeks later on May 21. It’s hard to listen to right now with the state of the world as it is, and was probably hard to listen to then. Yet a moment in time we should never forget and never stop learning from.

Aretha Franklin – “Think”

I truly wish Aretha was still with and screaming “freedom” like she does on this track. This track, along with “Respect,” were some of the first songs I heard from her as a young man and felt so inspired by her voice and passion. As tumultuous as 1968 must have been, 2020 feels right in line and this song speaks volumes to the lessons we can learn from our past.

Bruce Springsteen – “Born in the U.S.A.” (Demo Version)

To be honest, for the longest time I didn’t like this song. I grew up with the popular album version of this song blaring out of every dad’s speakers and even though I liked Bruce I just felt this song was so cheesy. It also seemed blindly patriotic and I never bothered to listen to the lyrics. It wasn’t until much later that I was digging through some demos that they had released that I heard this version. Once you sit and hear the lyrics against this minor chord backdrop it stands out as a great protest song.

Sam Cooke – “A Change is Gonna Come”

Closing out the playlist with a bit of optimism coming from the eternal Sam Cooke. Written as a response to the many instances of racism he was privy to, specifically when he and his band were turned away from a whites-only motel in Louisiana. This song will always work as a soundtrack to a revolution whose work seems like it’s never done. But hopefully we can learn from history and see how far we’ve come and have hope that we can keep going farther.

Photo credit: Bradley Cox