A small, enthusiastic audience of first arrivals chat in excited, hushed tones as they listen to Hubby Jenkins soundcheck into a pair of Ear Trumpet Labs microphones in the ballroom at Fort Worth, Texas’s Southside Preservation Hall. It’s an unseasonably cool Saturday afternoon in March, with crystal blue skies and wispy clouds backgrounding the historic Fairmount-Southside district. Over the next nine hours, ten musical acts will grace the stage. Many of them are already in the room, contributing to the light buzz and chatter; this already feels like a generative space.

In its third year, the Fort Worth African American Roots Music Festival (known lovingly as FWAAMFest) has a very specific vision within the Americana/folk/old-time/bluegrass festival space: to highlight the depth and breadth of contemporary African American roots music and, by doing so, underscore the seminal, vital contributions of Black folks to every single roots genre in this country. Presented by Fort Worth-based non-profit Decolonizing the Music Room (who BGS has collaborated with on multiple occasions), the event carries forward the organization’s mission, explained artfully and succinctly by DTMR founder Brandi Waller-Pace as she kicks off the day introducing Hubby Jenkins: “To center Black, brown, Indigenous, and Asian voices in music and related fields.”

“There are so many eyes and ears on culture and the arts in Fort Worth,” she continues. “And I want Fort Worth to be at the forefront of the conversation…”

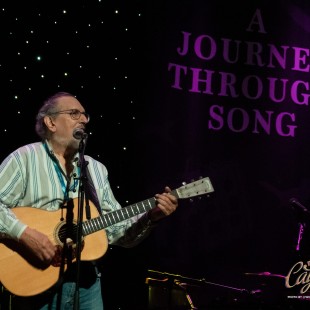

Hubby Jenkins began the day’s many conversations with a couple of banjo tunes, because, he admitted, “I’m a little nervous and [banjo tunes] make me feel cozy.” It was indeed a lovely, cozy easing into the day’s marathon lineup of music and presentations. During his set Jenkins picked guitar, banjo, bottleneck slide guitar, and played bones. And, he plays the festival’s first of many gospel numbers, “Jonah in the Wilderness,” inviting the audience to sing along, grounding his performance in the history of the Southside Preservation Hall space and these rootsy genres’ origins.

Kicking off the day with a gospel-filled set in a historic former church made so much sense, calling each of us as listeners to be active participants in the day’s festivities and also in its mission: to recenter these community-based musics on the folks who gave rise to each of them, reminding us we each have a role to play in telling a fuller, more just history of these musics.

Next up on the lineup is Justin Golden, who jokes that he and Hubby run into each other on gigs constantly and have the same repertoire, but from the outset his similar-seeming act couldn’t have felt more different. Working within the same vernacular and with such broad overlap, Golden and Jenkins are each still so distinct and unique – and illustrate the wide variety intrinsic to Black and African American roots musics, even within one form. Golden’s first number is an original, “I Hate When She Calls.”

He peppers older, classic Texas blues numbers – though he admits this is his first time in Texas – throughout heartfelt, poetic, and direct originals. His music’s foundation is fingerstyle blues, but with modern crispness, timeless touches, and a crystalline, focused singing voice.

Festival-runner and founder Brandi Waller-Pace stepped back on stage, this time as performer, for the next set of the day with songwriter, composer, and banjoist Kaïa Kater as the debut performance of their duo, Sable Sisters. They swap out banjos and guitars and a bass, singing folks songs and originals with nearly familial harmonies. A double clawhammer banjo cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Happier Than the Morning Sun” is their set’s highlight, with the legendary Justin Robinson’s guest appearance to play a set of old-time tunes ranking an honorable mention. Other festivals would be wise to consider booking Sable Sisters; if duo supergroups were a thing, this is one. Superduo? You get my meaning.

Between each set of music, as the stage was changed over, representatives from partner organizations, sponsors, and community leaders spoke to the audience, which slowly grew from a couple dozen into a small-but-mighty one to two hundred attendees. Tables in the lobby featured literature, information, and calls to action for DTMR, FWAAMFest, and these partner orgs – and from the back of the ballroom wafted the tantalizing aromas of Lil Boy Blue BBQ. (If only all music festival barbeque offerings were this legit.)

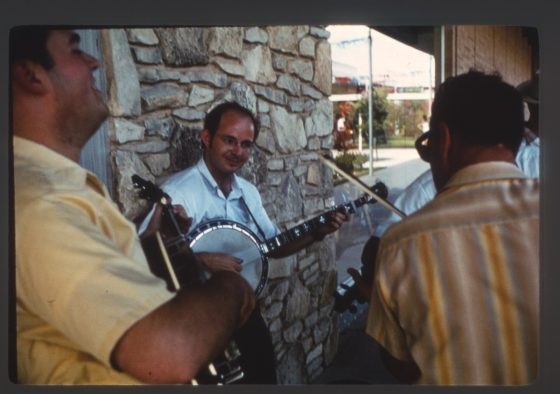

After Sable Sisters’ set concluded, the next event was a live podcast taping featuring a collaboration between Rissi Palmer, of Color Me Country Radio on Apple Music, and Garrett McQueen of Trilloquy Podcast. The conversation was titled “Redefining ‘Classic’” and featured Palmer, McQueen, and their FWAAMFest lineup-mates Jake Blount, Demeanor, Hubby Jenkins, and Dr. Angela Wellman. Palmer and McQueen took turns prompting their panelists to consider ideas around canon, genre lines, what terms like “classical” really mean, and so much more.

A theme that emerged throughout the taping was how often there aren’t hard, fast, concrete answers to these big, zoomed out questions about justice, representation, art, creation, space/placemaking, and community building. The panelists and hosts encouraged and challenged each other and themselves, reminding all of us that engaging in these kinds of conversations is part of the process and having the space – like FWAAMFest – to engage, build, and hold community like this is so important.

View this post on Instagram

It’s not lost on myself or perhaps anyone else in attendance just how much gratitude each of these participants have at being enabled to be in this FWAAMFest space. Each of the performers and speakers, in their own way and in their own words, effortlessly carried the event’s mission with them as they brought themselves to the space, wholly and vulnerably and powerfully.

The podcast recording gear struck, rapper and banjo player Demeanor took the stage for his first ever full-band set – and it was revolutionary. During the Trilloquy x Color Me Country conversation Demeanor (given name Justin Harrington) stated so eloquently that “Rap is folk music, because hip-hop is an indigenous Black American art form… From the porch to the stoop.”

He and his band immediately and indelibly illustrated his point with an energized, powerful set based on sometimes spitfire, other times free flowing rap lyrics with poppy, sung verses and choruses. It’s lyrical, content rich, witty and sharp. Demeanor’s writing and production style are full of forward motion, punctuated by arena rock guitar and Wooten-like bass lines. While often centered on banjo, the five-string is not the only way roots music oozes from these songs. Their lyrics and hooks are sharp and the vocals are strong – his singing isn’t an afterthought or simply in service of a hook. Several songs were from an upcoming unreleased album, including one stand-out track said to feature Rhiannon Giddens (his aunt) and Charly Lowry.

The delight of Demeanor gave way to the delight of dance and musical dialogue, as longtime friends and jaw-dropping collaborators Jake Blount and Nic Gareiss took the stage. Blount began the set solo, accompanied starkly by low, droning synth sounds gently, languidly warbling through half tones as he sang, dirge-like, above the sound bed, commanding silence. Blount brings us back to gospel, again looking backward to look forward, and in just a couple numbers the droning synth gives way to droning fiddle.

Gareiss and his singular approach to percussive dance and traditional step-dancing injects energy and joy into the crowd, who’ve been listening and engaging for almost six hours now. Audience members are on their feet, often with phones out, disbelieving the stunning musicality of Blount and Gareiss together, sixteenth notes perfectly, bafflingly in sync.

Nic dancing to Jake’s fiddle recalls the interconnectedness of Irish step dance and Black percussive dance traditions. Where cultures, practices, and folkways overlapped at the lowest of classes in America’s urban centers, dance flourished and Irish step dance cross pollinated with Black movement traditions and Appalachian and southern steps. Over the past century and more, movement and roots music have often been compartmentalized, privatized, and sequestered from each other. Bringing them back together in this intentional way is not just a radical act given the identities represented – in this duo and in this day of programming – but simply by existing together, with intention, Blount’s and Gareiss’s talents underline what these musics were initially created to do, say, and be.

The vibe in the Southside Preservation Hall ballroom at this point was reaching “full blown party,” and when the first of the festival’s headliners, Tray Wellington Band, took the stage the energetic momentum was raised further still. For all intents and purposes a straight-ahead bluegrass band, Tray Wellington’s four-piece group demonstrated this IBMA Award winner has found his voice. His critically-acclaimed album Black Banjo certainly feels mature and fully-realized, but this was the first this writer had caught Wellington’s band since long before that record was released. The growth they’ve sustained, musically and as a unit, in the interim is remarkable. They execute chamber music level virtuosity, but with bluegrass bones. With Katelynn Bohn (bass), Josiah Nelson (mandolin), and Nick Fallon Weitzenfeld (guitar), Tray references Dawg, Béla, New Grass Revival and many more, but with an underpinning that feels as bluegrass as Appalachia – say Johnson City, TN, where he’s from.

They play a Kid Cudi cover, which is promised to be on an upcoming release, and the audience descends into mayhem as the melodic hook is slowly recognized in ripples throughout the crowd. Whether covering hip-hop or playing an old-time tune, these pickers demonstrate amazing soloing: modern, in-the-moment musical ideas without ego or self-absorption. And with Tray’s right hand anchoring all of the above, it reminds of Earl Scruggs in his Revue days – solidly bluegrass, but intimating musical ideas that come from so far afield, way beyond what we consider bluegrass territory.

Chambergrass, or whatever you want to call it, is seen as more “high-brow” or “intellectual” given its adjacency to conservatories and storied music schools, but this style of virtuosic playing is so well placed within the musical vocabularies of people from the region that birthed string band traditions. And in this context it can be executed with equal ease, aplomb, and athleticism, and with a much more grounded approach.

A quiet, slightly exhausted euphoria tingles through the stalwarts of the crowd who remain for Jackie Venson’s no-holds-barred FWAAMFest finale. Waller-Pace returns to the stage one final time to introduce the night’s last headliner, with her daughter Sparrow (who waits patiently to get her Jackie t-shirt signed at the end of the night.)

Venson is accompanied only by drummer Rodney Hydner – and her signature DJ sampler that allows her to play along with tracks, sound beds, background vocals, and play solos over loops. Even with just a two-person act, her trademark joy immediately washes over the entire room and re-energizes the crowd. Venson’s songs are soaring, anthemic, and huge, matched only by her broad grin as she smirks and laughs at herself and her own playing like it’s an inside joke.

Perhaps the best guitarist of her generation, certainly the best rock-blues guitarist of the past thirty years, the internet is in a four to six week feedback loop of discovering and rediscovering Venson’s playing at the moment, with her Tweets and TikToks seemingly going wildly viral about once a month. She’s been retweeted and signal boosted by a who’s who of Twitter personalities and musicians, and it’s all because hers is a singular voice, perspective, and skill.

Watching her improvise over each song recalls Nic Gareiss’s dancing from earlier in the evening. When you’re watching something so visceral and in the moment, you can’t help but inhabit that moment with them. And many of us do inhabit these moments with Venson by moving, standing, dancing, reveling in the ever-present joy of her music.

Venson’s brand of modern blues is unconcerned with divorcing itself from the blues of the past (and of the present) that some feel is stoic, stuffy or dusty, and out of step with modernity. Her brand of blues, no matter how distant it has traveled from its roots, still honors the sounds of old-time and ragtime and down home blues, because it knows where it came from and to what it’s connected. Venson’s connections to Texas and Austin further reinforce this point – and help place Venson and her style of playing squarely within “guitar culture,” too.

At one point during her performance Venson marveled at how the FWAAMFest gathering was, in her words, “Pretty legendary!! You’re going to be talking about this in 10 years, telling people you saw everybody on this lineup here today.”

It was a feeling that began creeping up much earlier in the festival, that what we were present for wasn’t just a community music festival, it was so much more.

Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, and Disabled folks – artists and creators and movers and musicians – continue to offer and model ways to hold the past within ourselves while looking ahead to the future, a duality that modernity and westernism struggles to acknowledge or inhabit. What’s striking about this conglomeration of creators and musicmakers on this lineup at this festival is that they make it look easy. It seems effortless to understand, uplift, and uphold a mission like FWAAMFest’s. Partly because the participants all are stakeholders in that mission to begin with! With their music, their insights, and their storytelling these musicians and thinkers demonstrate the past is the future and the future is the past. Roots music – the kinds that center the experiences, stories, and seminal contributions of Black, Brown, and Indigenous folks – can spotlight and move through this dichotomy better than so many art forms, while remaining grounded firmly in the present.

FWAAMFest’s success wasn’t simply because it’s a festival with a novel, substantive mission. It was a soaring, generative, forward-looking success because it focuses on what “the mainstream” perceives as a niche within a niche within a niche – African American roots music – and shows all of the possibilities, all of the many universes of artistic expression endemic to such a niche. The specificity here is not prohibitive or exclusive, it’s unfailingly, infinitely expansive. In sound, genre, content, tradition, and beyond.

As Jackie Venson said, we all will still be talking about 2023’s Fort Worth African American Roots Music Festival for many years into the future.

Editor’s note: Follow Decolonizing the Music Room on social media to catch footage from FWAAMFest 2023 as it’s released and make sure to DONATE to support their mission and future FWAAMFests!

Photos by Ben Noey Jr.