The Earl Scruggs Revue’s only movie soundtrack, Where The Lilies Bloom (1974), is not well known. That’s a pity because in 1973, when it was recorded, the band had been together for four years and was a very solid outfit. At the beginning of 1973 the group included Earl, Randy, and Gary Scruggs, Josh Graves, and Jody Maphis. Steve Scruggs was an occasional member. Vassar Clements’ last credited appearance on record with the Revue was on Earl Scruggs‘ Dueling Banjos (C 32268), released early in 1973, and he was still with them when they recorded the soundtrack.

The movie was filmed between May and August 1972 and released in 1974 through United Artists. The soundtrack album, Columbia KC 32806, is credited to the Revue and their longtime producer, Ron Bledsoe. Movie soundtrack recordings are made after the film has been edited; the musicians perform in a studio setting while the film is rolling. This is a precision business, obviously; I have yet to find accounts of the Revue’s involvement in this process, which must have taken place in early 1973.

Soundtrack albums focus on eliciting memories of the film. Viewing and listening are, in the final analysis, two very different things. The music in Where The Lilies Bloom was, in the first instance, the musicians’ responses to the visuals, shaped by the movie producer and director.

Earl came up with new tunes and restatements of old ones; Randy contributed deft and creative electric and acoustic guitar, both flatpicked and fingerpicked; Vassar performed masterful fiddle from a point in his career when he was doing the old-time tunes brilliantly while developing his new jazz-inflected style; and Josh played the creative and brilliant Dobro that a generation would follow.

The film’s producer, Robert B. Radnitz, based the picture on Vera and Bill Cleaver’s award-winning young adult novel of the same title. It tells the story of the struggle of the Luther family siblings, four young Appalachian country youths – the oldest is 16 – to live at home together following the death of their widower father. They do this by “wildcrafting,” gathering and selling wild herbs as health supplements. The narrative focuses on the two teen daughters’ growth and relationships.

Where The Lilies Bloom was shot on location in Watauga County on North Carolina’s northwestern border. Producer Radnitz strove to employ workers from Appalachia, such as screenplay writer Earl Hamner Jr. and actor Harry Dean Stanton, who had a leading role as the older “Kiser Pease.” The young actress who had the leading role as 14-year-old “Mary Call Luther,” Julie Gohlson, was a Georgia native chosen after a nationwide search. She was nominated for a Golden Globe in 1975. This was her only movie appearance.

Radnitz worked with toymakers Mattel on this co-production, their second. The first was Sounder, released in 1973. That acclaimed film about young teens in Black Mississippi propelled Cicely Tyson to stardom and featured blues star Taj Mahal for its soundtrack. For his second movie’s soundtrack, Radnitz again sought music reflecting the cultural background of the film’s narrative – in this case, the oral traditions of Appalachia. He chose the Earl Scruggs Revue.

The film got a good reception, with prizes and nominations of various sorts. It’s well worth watching – not only is there a DVD with commentary, it’s also available VOD on YouTube and is available to watch via select streaming services. The album, on the other hand, pretty much sank like a stone – no ripples. But if you want to hear what the Earl Scruggs Revue sounded like when they were together just playing by themselves, with no added stars in the studio, this is the album to try. There’s plenty from them to appreciate on the film’s soundtrack, as well. A lot of nice creative moves here!

This was a hard album to find. By the time I finally got it in the ’80s I wasn’t as interested in the band as I’d been earlier. I listened once, filed it away, and only listened again recently. Holding and looking at the album cover during this playback reminded me why I only listened to it once before. The liner notes must have been composed by some 9-to-5er at United Artists. There’s nothing there about the music. Who’s the female vocalist? What’s the band doing? No mentions. The visuals and most of the copy are from the movie. Not much of a musical souvenir!

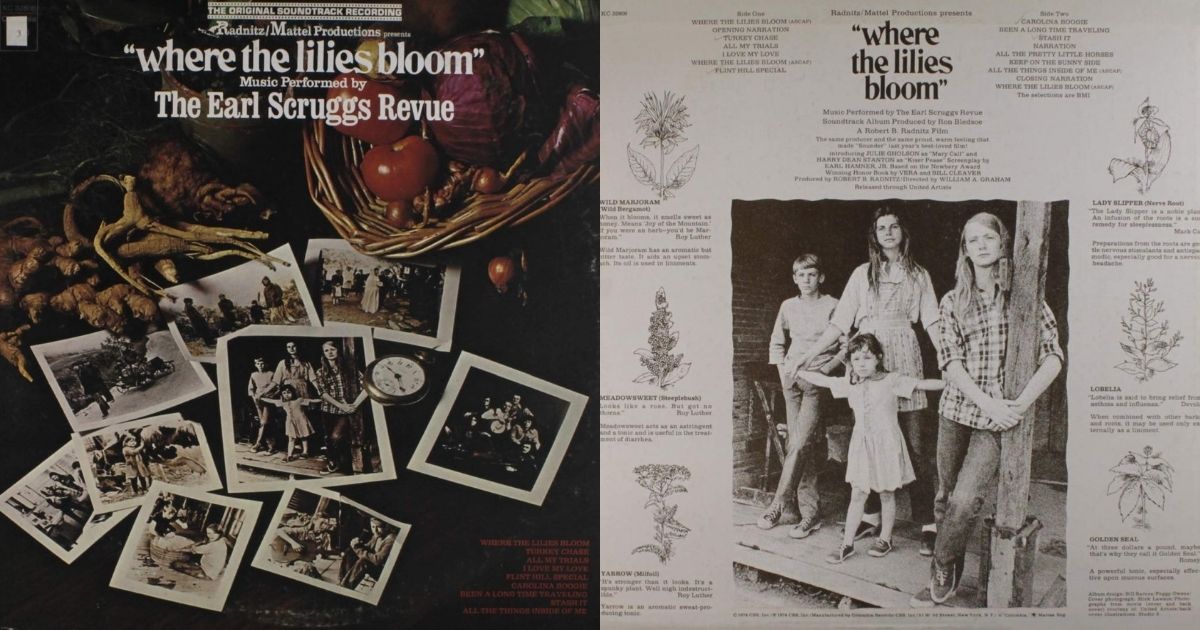

The album cover of Columbia KC 82806 announces at the top: “The Original Soundtrack Recording.” Below that comes “Radnitz /Mattel Productions presents, where the lilies bloom (all in large lowercase), then: “Music Performed by” and finally “The Earl Scruggs Revue.” All this is printed over a collage of color shots of herbs, along with nine little black and white stills from the film – one of which is the Revue.

On back of the album cover, we are told this is a ”Soundtrack Album Produced by Ron Bledsoe [for] A Robert B. Radnitz Film.” Cast members (but not band members) are listed. Next to this info are small columns, left and right, that list the tracks. Filling the center below all this is a large still of the film’s young lead actors; on either side of this are illustrations of wild herbs – three on each side.

In spite of the Revue’s lack of prominence on the album’s notes, I think that the band did a good job of coming up with new compositions and old-time tunes that represent their music in imaginative arrangements relating to the context of the film.

After relistening to the LP, I bought the film’s DVD, which was remastered and released in 2022 with an audio commentary by filmmaker and historian Daniel Kremer. The film opens (as does album track A1) with song “Where The Lillies Bloom” sung by its composer, Barbara Mauritz.

Singer-songwriter Mauritz (1949-2014), originally from Texas, was the vocalist with Lamb, an avant-garde folk-jazz-rock fusion group active in San Francisco in the early ’70s. Her first solo album, Music Box, was released on Columbia in 1972.

How did she end up on this movie’s soundtrack? I wish I knew! Being a Columbia artist was probably not coincidental. As we hear, she’s paired with another Columbia artist, Earl Scruggs, on the theme song at the opening. The Revue is laid-back in the track’s background at the start; eventually Randy’s guitar plays the melody, while Earl’s banjo sneaks up to end with beautiful 6/8 triplets in the background, and a few of Josh’s Dobro licks can be heard.

This is music meant to be heard in accompaniment to the visuals that open the film, aptly demonstrated by its trailer, which opens with the character “Devola Luther” (the oldest sister, played by Jan Smithers) singing “A Long Time Traveling” a cappella. The guitar is very much in the background, as is the banjo, which comes up only at the end.

The album contains three “Narrative” tracks by lead character Mary Call Luther which explicate the dramatic turning points in the film’s story. Following the first narrative track, A2, comes “Turkey Chase”, track A3, which plays beneath a scene in which the Luther children are trying to catch wild turkeys.

The Revue is actually playing the traditional fiddle tune “Chicken Reel,” led by Earl with brief interludes by Randy (lead guitar) and Josh Graves (Dobro). This is two minutes of really good straightforward old-time music, which the Revue knew well but rarely recorded.

The next track (A4) presents slow, moody instrumental music that plays behind scenes pertaining to the father’s death: “All My Trials,” a traditional spiritual with Bahamian connections popularized by Joan Baez in the ’60s. Randy’s lead guitar mixes with some nice piano, probably by Mauritz. It’s a pretty performance.

Track A5, “I Love My Love,” which plays behind a romantic sequence, was also popular in the folk revival. English composer Gustav Holst described it as a “Cornish folksong” in his arrangement of it. It’s sung here by Mauritz, over a finger-picked guitar which could be hers, or maybe that of Randy or Earl.

Track A6 repeats the theme, “Where The Lilies Bloom,” as a slow instrumental piece in 4/4 time. Randy’s finger-picked guitar plays it twice, and then Gary’s bass and Earl’s banjo join for two more verses. It really demonstrates Earl’s artistry – such control, economy, lyricism!

In the film’s soundtrack, The Revue plays Earl’s “Flint Hill Special” behind several action scenes – countryside automotive rambles – as Mary Call and the family are in conflict with Kiser. Here’s what that sounds like as played by Earl, Josh, and Vassar on the soundtrack:

The original pressing of the LP diverges from the movie soundtrack at this point, on Track A7, which is also identified as “Flint Hill Special.” No doubt that garnered Earl some royalties for his composition of that name, but the tune played on the original album is the traditional “Sally Ann,” a piece Earl recorded on his 1961 Foggy Mountain Banjo release. (This seems to have been corrected on digitally distributed versions of the album. Hear the LP’s version of “Sally Ann” below.)

It’s an interesting new version, opening with a couple of fiddle licks and then shifting to the percussive sound of the banjo strings being played with right-hand fingerpicking (a “roll”) while the strings are muted with the heel of the left hand. Then the fiddle steps up while at the same time Dobro, bass, and guitar enter – a powerful old-time bluegrass sound. Earl’s banjo takes over second time through, then the fiddle returns and finally Earl closes as he began, percussively. The “shave and a haircut” ending is dominated by Randy’s fancy guitar.

Side two of the album (track B1) opens with music from a scene in which the four Luthers, who’d been at the grocery store learning about wildcrafting, get a ride home from the store owner “Mr. Connell” (played by Tom Spratley). Here, the Revue is heard playing “Carolina Boogie,” basically an update of Earl’s up-tempo blues in G, “Foggy Mountain Special.” It features the entire Revue with a considerable amount of call-response between Randy and Vassar and a great ending.

The family’s funeral for the mountainside burial of their father includes “Been A Long Time Traveling” (track B2) sung a cappella by oldest daughter character, Devola. It’s heard twice, at the beginning and the close of the burial scene.

Following this, the film’s narrative shifts to wildcrafting, with Mary Call’s next visit to the grocery store to sell herbs backed by the Revue playing (track B3) Earl’s “Stash It,” a catchy banjo tune which starts slowly and speeds up.

Next, Mary Call’s poem about witnessing a starburst is heard on track B4, with subtle guitar and piano backup. It’s followed (track B5) by “All The Pretty Little Horses,” a traditional lullaby of African American origin, performed solo here by Randy’s fingerpicked guitar. In the film this plays behind a tender scene in which the Connells visit the Luther home.

Later, as the Luther children are depicted gathering herbs, the melody of the old Carter Family song “Keep On The Sunny Side” (track B6) is heard. First, it’s finger-picked by Randy on guitar, then Earl’s banjo comes in doing harmony. Neat! This is the ultimate father and son duet; Gary, on bass, is close by.

As the narrative approaches climax, we hear Barbara Mauritz singing her “All The Things Inside of Me” (track B7), accompanied by fingerpicked guitar, probably by Randy but possibly by Mauritz herself.

Mary Call’s final narrative (track B8) leads to the full band playing the theme; it’s heard at length as the film’s credits roll.

The preceding description, based on the album, does not point out all the places where the Revue’s music is heard on the film soundtrack – scenes where Randy’s guitar, Gary’s harmonica, Josh’s Dobro, and Vassar’s fiddle add aural nuances to the screenplay. Throughout the film, music editor Robert Takagi places in the aural background little quotes taken from performances like the final version of the theme. Randy’s guitar, in particular, is heard behind several scenes.

Other musical segments in the film are not heard on the album at all, but play a central role in evoking the film’s cultural milieu. Thus, while rambling in the car, they turn on a local radio station: the Revue is heard playing county-rock. Elsewhere, as they are walking home from wildcrafting, there’s a nice a cappella performance of “Feast Here Tonight” by youngest Luther daughter “Ima Dean” (played by Helen Harmon).

These musical segments remind us that the Revue, while featured on the album, is really playing in support of a story, a visual drama. As such their music here is different from that found on all their other albums. It does not sell the sound of the band – it speaks for images of the region’s atmosphere and its culture that emerge in the film’s narrative.

Read more about the Earl Scruggs Revue and find our entire archive of Neil’s Bluegrass Memoirs column here.

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo Credit: Terri Thomson Rosenberg

Edited by Justin Hiltner.

In the 1940s, this was one of the first nightclubs to feature folk music. The great protest and folk singer Josh White held court at Café Society for five years. Billie Holiday and Lester Young were regular performers in what was one of the first clubs to truly break color barriers. When Dylan lived here in 1962, it was the Haven — one of New York’s largest openly gay nightclubs.

In the 1940s, this was one of the first nightclubs to feature folk music. The great protest and folk singer Josh White held court at Café Society for five years. Billie Holiday and Lester Young were regular performers in what was one of the first clubs to truly break color barriers. When Dylan lived here in 1962, it was the Haven — one of New York’s largest openly gay nightclubs. Keep heading toward Dylan’s apartment and then turn right on Jones Street.

Keep heading toward Dylan’s apartment and then turn right on Jones Street. This is the street from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album cover. Take some photos and continue down the street — at the end is Caffe Vivaldi. Pop in for a beer. It’s a great place to hear some burgeoning New York musicians, as it is still home to songwriters and one of the only clubs with a piano. It’s a great old room.

This is the street from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album cover. Take some photos and continue down the street — at the end is Caffe Vivaldi. Pop in for a beer. It’s a great place to hear some burgeoning New York musicians, as it is still home to songwriters and one of the only clubs with a piano. It’s a great old room. This room has a rich history. It was first the Commons. Opened in 1958, the Commons was originally a small theater and café that was tres bohemian. It was also one of the first basket houses — a coffee shop that had live music — in Greenwich Village. The performers were paid in tips, which were collected in a passed basket. The Commons expanded in 1960 and changed its name to the Fat Black Pussycat. This is where Dylan wrote "Blowin' in the Wind."

This room has a rich history. It was first the Commons. Opened in 1958, the Commons was originally a small theater and café that was tres bohemian. It was also one of the first basket houses — a coffee shop that had live music — in Greenwich Village. The performers were paid in tips, which were collected in a passed basket. The Commons expanded in 1960 and changed its name to the Fat Black Pussycat. This is where Dylan wrote "Blowin' in the Wind." Dylan performed at Café Wha? on his first day in New York. It was an open mic hosted by Fred Neil. Fred Neil is best remembered as the songwriter behind “Everybody’s Talking” from the film Midnight Cowboy. In 1961, he managed the café’s day bookings and MC’d the open mic. Dylan did a set of Woody Guthrie songs and Neil hired him on the spot as his harmonica player.

Dylan performed at Café Wha? on his first day in New York. It was an open mic hosted by Fred Neil. Fred Neil is best remembered as the songwriter behind “Everybody’s Talking” from the film Midnight Cowboy. In 1961, he managed the café’s day bookings and MC’d the open mic. Dylan did a set of Woody Guthrie songs and Neil hired him on the spot as his harmonica player. This café is virtually unchanged from the day it opened. Without a doubt, Dylan spent time here. You might also recognize it from the film Inside Llewyn Davis. Caffe Reggio also claims to be the birthplace of the cappuccino.

This café is virtually unchanged from the day it opened. Without a doubt, Dylan spent time here. You might also recognize it from the film Inside Llewyn Davis. Caffe Reggio also claims to be the birthplace of the cappuccino. The Gaslight was the place to play in the 1960s. It was the Carnegie Hall of folk music, where Dave Van Ronk hosted the weekly hootenanny every Monday and Dylan was one of the regular performers within a year of moving to town. There were typically five performers each night and they would rotate every four songs. It is a tiny spot, and there would be lines stretched down the block. Before being converted to the Gaslight, this was the coal room for the building. The walls were stained black from years of storage, but the room embraced it and left it dark. It’s also been rumored that this is where the beatniks began snapping instead of clapping, so as not to disturb the upstair tenants.

The Gaslight was the place to play in the 1960s. It was the Carnegie Hall of folk music, where Dave Van Ronk hosted the weekly hootenanny every Monday and Dylan was one of the regular performers within a year of moving to town. There were typically five performers each night and they would rotate every four songs. It is a tiny spot, and there would be lines stretched down the block. Before being converted to the Gaslight, this was the coal room for the building. The walls were stained black from years of storage, but the room embraced it and left it dark. It’s also been rumored that this is where the beatniks began snapping instead of clapping, so as not to disturb the upstair tenants. This is the former Kettle of Fish. When not performing, the musicians would eat and play cards up here.

This is the former Kettle of Fish. When not performing, the musicians would eat and play cards up here. Izzy Young from the Beatnik Riots was the proprietor. Dylan referred to the Folklore Center as “The Citadel of American Folk Music.” Izzy was a notoriously bad businessman, but his folklore center was the hub of the New York folk revival. Van Ronk, and countless other musicians, were technically homeless — although they always had a place to crash. This was where their mail was sent. It was also where Dylan came to absorb records and learn new songs.

Izzy Young from the Beatnik Riots was the proprietor. Dylan referred to the Folklore Center as “The Citadel of American Folk Music.” Izzy was a notoriously bad businessman, but his folklore center was the hub of the New York folk revival. Van Ronk, and countless other musicians, were technically homeless — although they always had a place to crash. This was where their mail was sent. It was also where Dylan came to absorb records and learn new songs. Continue to 152 Bleecker Street where the old Café Au Go Go is now a Capital One Bank. Café Au Go Go was a cultural hotbed in the 1960s hosting folk, jazz, comedy, blues, and rock. The Grateful Dead played their first New York show at Café Au Go Go. A young Joni Mitchell had a weekly gig. Blues legends Lightnin' Hopkins, Son House, Skip James, Bukka White, and Big Joe Williams performed at the club after being "rediscovered" in the '60s. Young Bob Dylan spent many nights listening to his peers and forefathers.

Continue to 152 Bleecker Street where the old Café Au Go Go is now a Capital One Bank. Café Au Go Go was a cultural hotbed in the 1960s hosting folk, jazz, comedy, blues, and rock. The Grateful Dead played their first New York show at Café Au Go Go. A young Joni Mitchell had a weekly gig. Blues legends Lightnin' Hopkins, Son House, Skip James, Bukka White, and Big Joe Williams performed at the club after being "rediscovered" in the '60s. Young Bob Dylan spent many nights listening to his peers and forefathers. This is where Dylan came up with the Rolling Thunder Review. When he moved back to Greenwich Village in the '70s, he spent many nights at the Bitter End. There were many late-night jam sessions and, one night, he decided to take this loose collective on the road. He recruited some of his famous friends, hired a film crew, and embarked on one of the most ambitious tours of the 1970s. The Bootleg Series put out an amazing double album, and Heavy Rain was recorded on this tour. If you’ve ever seen Dylan in white face with a pimp hat, it was from the Rolling Thunder Review.

This is where Dylan came up with the Rolling Thunder Review. When he moved back to Greenwich Village in the '70s, he spent many nights at the Bitter End. There were many late-night jam sessions and, one night, he decided to take this loose collective on the road. He recruited some of his famous friends, hired a film crew, and embarked on one of the most ambitious tours of the 1970s. The Bootleg Series put out an amazing double album, and Heavy Rain was recorded on this tour. If you’ve ever seen Dylan in white face with a pimp hat, it was from the Rolling Thunder Review.