The beautiful voices of I’m With Her paid special tribute to the illustrious icon Dolly Parton in their latest visit to the studio for Live from Here. In an intimate performance, I’m With Her sing “Lover’s Return,” originally a Carter Family song, which Dolly, Emmylou Harris, and Linda Ronstadt revived only a few years before the turn of the century on Trio II. Now as a new decade is settling in, I’m With Her look back and remember, breathing new life into music that inspired so many — including Sarah Jarosz, Aoife O’Donovan, Sara Watkins, and of course, Dolly herself.

Tag: linda ronstadt

MIXTAPE: The Milk Carton Kids, In Harm’s Way

“There’s a paradox at the heart of great harmony singing: when voices combine in so elemental a way that they disappear into each other, the effect is dizzying, mystifying, disorienting, and yet by far the most satisfying sound in music. Here’s a VERY incomplete playlist, spanning a few generations, of bands defined by their harmonies, who set my mind spinning with their vocal arrangements, execution, and pure chemistry as singers.

“Full disclosure: my own band is included aspirationally and for the sake of self-promotion. Author’s Note: Sorry not sorry for naming this playlist with a pun.” — Joey Ryan, The Milk Carton Kids

The Jayhawks – “Blue”

That unison in the first few lines is so thrilling cause you know what’s about to happen, and when the parts separate it just feels so good.

Gillian Welch – “Caleb Meyer”

The harmonies and Dave’s playing are so intricate in this song you’d be forgiven for glossing over the lyrics, which tell the story of an attempted sexual assault victim killing her attacker with a broken bottle. Check out the Live From Here version with Gaby Moreno, Sarah Jarosz, and Sara Watkins, and catch the alt lyric subbing “Kavanaugh” for “Caleb Meyer” about halfway through.

Gram Parsons & Emmylou Harris – “Hearts on Fire”

Just one of the all-time great duets. Who’s singing the melody, Emmylou or Gram? Hint: trick question.

Our Native Daughters – “Black Myself”

Do all supergroups hate being called supergroups? I wouldn’t know. Our Native Daughters is a supergroup though, and the power of their four voices in the refrains and choruses of this one are all the proof I need.

Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt, & Emmylou Harris – “Those Memories of You”

It’s insane that three of the great singers of their generation just so happened to have this vocal chemistry. Their voices swirl together like paint and make a color I’ve never seen before.

boygenius – “Me & My Dog”

Favorite game to play when this song comes on is “try not to cry before the harmonies come in.” Very difficult. Impossible once they all sing together.

The Smothers Brothers – “You Can Call Me Stupid”

GOATS. IDOLS. Favorite line is, “That’s a pun isn’t it?” “No, that really happened.”

The Milk Carton Kids – “I Meant Every Word I Said”

My band. Imposter syndrome. We recorded the vocals on this whole album into one mic together. It helps us disappear our voices into each other’s.

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young – “Carry On”

For me, CSNY are the pinnacle of that disorienting feeling harmonies give you when you just have no idea what’s going on. I’ve never been able to follow any one of their individual parts and I LOVE that.

Sam & Dave – “Soothe Me”

When the chorus comes around and you can’t decide which part you want to sing along with, you know they did it right.

Louvin Brothers – “You’re Running Wild”

The Louvins sound ancient to me. Primal. The way their voices rub against each other in close harmony is almost off-putting but I’m addicted to it.

The Highwomen – “If She Ever Leaves Me”

There’s probably even better examples of the Highwomen doing that crazy thing with their four voices where they become one entirely unique voice, all together, but this song is just so good I had to go with it. And the blend in the choruses is just as intoxicating as it gets.

I’m With Her – “See You Around”

Really an embarrassment of riches in modern music on the harmony front. Hearing I’m With Her perform around one microphone drives me insane with the best possible mix of confusion, jealousy, and joy.

Mandolin Orange – “Paper Mountain”

The melancholy is so satisfying when either one of them sings alone, and then they bring that low harmony and I have to leave the room.

Skaggs & Rice – “Talk About Suffering”

This whole record is a masterclass in two-part harmony. It changed my entire concept of singing. I’m Jewish, but when this song comes on it makes me sing wholeheartedly of my love for Jesus.

The Everly Brothers – “Sleepless Nights”

The absolute masters of both parts of a two-part harmony standing alone as the melody. Credit to Felice and Boudleaux for that, for sure, but the Everlys executed it better than anyone before or since.

Simon & Garfunkel – “59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy) — Live at Carnegie Hall, New York, NY – July 1970

This is far from my favorite S&G song, but this live version especially showcases what geniuses they were at arranging crossing vocal lines, unisons, parallel melodies, nonsense syllables and swirling harmonies. Plus the nostalgic “awwww” from the crowd gives me hope that a sensitive folk duo could one day achieve mainstream success again.

Shovels & Rope – “Lay Low”

This starts out as a song of profound loneliness with just one voice singing, then the harmony comes in and it gets… even lonelier? Harmony is magic.

Boyz II Men – “End of the Road”

I’m a child of the ‘90s, don’t @ me. I never realized at all those 8th grade slow dances that we were subliminally being taught world-class harmony singing and arranging. Good night.

Photo Credit: Jessica Perez

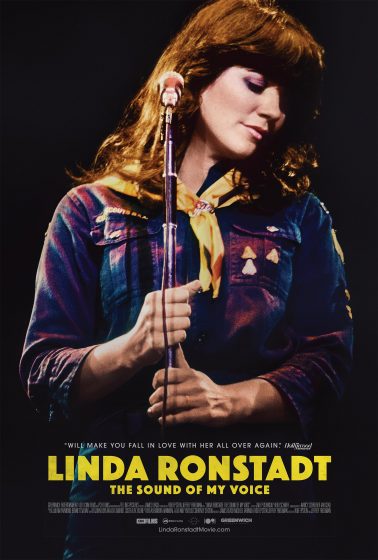

Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass (Part 2 of 2)

In honor of the new documentary film, Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, and in appreciation of her connection to bluegrass — and in an attempt to shout it from the proverbial rooftops! — we’re reprinting Dan Mazer’s 1996 Bluegrass Unlimited interview with Ronstadt split into two parts, but in its entirety on BGS. Special thanks to the team at Bluegrass Unlimited for partnering with BGS to spotlight how bluegrass has touched one of the most important and truly iconic voices to ever grace this planet.

(Read part one of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

“Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass”

By Dan Mazer. Bluegrass Unlimited, June 1996

…Our conversation moved to a discussion of Alison Krauss’ musicianship. Krauss seems to have an incredible variety of influences, which come out when she wants them to. “And in an appropriate manner,” Ronstadt continued. “There seems to be a general agreement among all the people that I know – whose various subjectivities are very strict and very demanding – that Alison has the best taste of any of those people.

“Every fiddle player that I’ve ever worked with will be tempted to play sound(s) like donkeys braying; or just play too much – play ‘flash’ licks in an inappropriate manner. (I call it) ‘The Paganini Syndrome.’ And Alison never is.

“Her pitch is completely stunning! I’m a pitch nazi, and she’s even a little more strict than I am, in terms of pitch. And the thing that I like the very best about her playing is her rhythm. She’s got that great, easy, loping sense of the groove that bluegrass players generally don’t have. When it’s right, of course, it’s got a great swing to it. But bluegrass players have a tendency to get a little stiff and a little on top of the groove. And she never does! I don’t think she’s played with drummers that much, but we put her together with Jim Keltner, and it was just an amazing thing. She’s got the same sense of the groove that he does, and he has the effortless pocket. I consider her as good as any musician I’ve ever worked with. My cousin (David Lindley) said she was his favorite fiddle player ever. And I love her. And also, she owns Maria Callas’ bed! (Laughter) I don’t know why, or how she managed to get her hands on it, but she did. I was jealous. I wanted to be the one to get it. Emmylou Harris and I are both Maria Callas fans. Slobbering, drooling Maria Callas fans!”

When asked to comment on other bluegrass acts, Ronstadt confessed that she doesn’t listen to any modern music of any style. In fact, she was unfamiliar with many of the major country acts. Nor had she ever heard of the IBMA. “Honestly, the only ones I know (are) Ricky Skaggs, Alison, and (the) Seldom Scene,” she said. “But before that, it really was those original guys (Flatt and Scruggs and Monroe). I mean, it was such a short-lived era. And before that, the Blue Sky Boys, which wasn’t really bluegrass, but which really sorta fed right into it. I love those guys, and I listen to the Louvin Brothers a lot. So I listen to all the stuff that led right up to it.

“I know very little of any kind of contemporary music. I just don’t. I listen to NPR, and I listen to Maria Callas and them, and I listen to a lot of Mexican music, and that’s about it. And if it penetrates through that it’s usually because Emmy calls me up, or John Starling calls me up, or Quint Davis. Quint Davis is the guy that runs the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and he put on that thing on the Mall for the inauguration. That’s where I saw Alison. I was just blown away by her!

“I don’t know modern stuff. I haven’t a clue. It seems like when we did the ‘Trio’ record, nobody was interested in traditional music. And then that record was pretty successful, and at that point, Ricky Skaggs was extremely successful, but all of a sudden, I don’t know. I don’t watch this type of stuff on television. I haven’t got the vaguest idea, and I don’t listen to the radio. I have a great respect for anything that anybody does. I mean, I think it’s just so hard to make a record – any record – that I don’t like to put myself in the position of, ‘This is good, and that’s not good,’ like a bean-counter. But I have to say that (modern country fails) to capture my interest.

“There’s always music in front of my face. If I was gonna sit and listen to Mozart, (and) someone said, ‘OK, this is gonna be it (you can only listen to Mozart) forever,’ I’d go, ‘OK.’ And if someone was playing me some Mexican traditional music, and they said, ‘This is gonna be it forever,’ I’d go, ‘OK.’ Because there’s enough in any of those things, to (keep me interested).

“Somebody came over to my house the other day with some musicians from Madagascar. They sit down in my kitchen and played this Malagassi music, and it just blew me through the wall! So, if they had said at that point, ‘Well, you’re gonna have to sing a little Malagassi now,’ I would’ve said, ‘Well, OK. Fine!’ I could’ve got right down and sung with them, and had no problem at all. But I can only concentrate on one thing at a time, and if that thin is interesting, I just don’t have any particular need to shift my attention.

“When John Starling comes out to visit me, he sits down at my kitchen table with his guitar, and we start singing. I get pried back to English. But I’d really rather sing in Spanish or Italian. Because all that stuff (bluegrass and country) is based on rural southern pronunciation. And in Spanish – if I’m singing a Latin jazz thing that’s a Caribbean base, I have to push myself from my northern Mexican rural accent into a Caribbean accent, which is painful for me. I find it an unpleasant way to pronounce the language, but I have to do it in order to get the rhythms right. So I do it. I really push myself into that other accent. But I prefer singing in my own accent – the accent of my family’s region. I can just get so much more sound out of my voice in that language.”

Over the course of a career, an artist makes many decisions based upon the age-old dilemma of commercialism versus artistic merit. What the public wants to buy is not always what the artists likes [sic] to paint, play, or sing. Ms. Ronstadt has lately recorded opera, Big Band and Mexican music, none of which usually sells platinum in today’s market. It seems that she has reached a point in which she doesn’t have to worry about selling a certain number of records; her musical decisions are now totally artistic. “Well, they were to start with, too. It’s just that I wasn’t as good at executing them!” She protested with a laugh. “And I find that now. I’m making my choices based on an artistic thing, but I am also finding that my choices were made for me when I was a baby. It’s getting harder, though. I do find that the record companies have a tendency to stick their oar in a lot more now. It’s very nervous-making. Although, the one person that I’ve allowed to submit material and give advice – I don’t always take it, but I always consider it – is (Asylum Records President) Kyle Lehning. He’s an amazing guy! He really, genuinely likes music, first of all, which is rare for a record person. Second of all, he’s extremely knowledgeable, and he has great taste in songs. And he seems dedicated to the idea of trying to save what he can that’s quality, and nurture it.

“(The latest project) started with several nagging phone calls from John Starling!” She laughed. “John Starling doesn’t get down behind traditional Mexican music! And then Emmy calling me, because Emmy and I are such fans of the McGarrigle Sisters. We were talking about doing some television stuff. We were just trying to think of how we could get in the living room together again with John Starling. So we started working on tunes, like the Carter Family songs that only Emmy and I would be interested in. And maybe John Starling or Claire Lynch, or somebody. John had, a long time ago, sent us Claire Lynch records, saying, ‘You really gotta sing with this girl. She’s real wonderful.’ So claire and Emmy and I have done some stuff together.

“And then, I’ve been working with Valerie Carter. She put a record out in the ‘70s. Everybody in Hollywood was after her. She’s an extraordinary singer, and she was exceptionally beautiful. She was about 19, I think, then. Lowell George and Mick Jagger and Jackson Browne and J.D. Souther and Danny Kortchmar – everybody wanted to work with her. Everybody tried to, and then George Massenberg, who is my production partner – who I met through John Starling – did produce a record from her, and so did Lowell George. I sang on it. Then she just had some problems, and she dropped out of sight for about 15 years, which was really a tragedy for us. ‘Cause she’s one of those girls that can sing as well as Whitney Houston. She’s got that kind of chops. But it doesn’t sound like her. It’s a very distinctive voice. But that kind of ability. It was too bad, ‘cause she was (a) really interesting singer. So she’s now been singing on the road with James Taylor a lot. I used her to sing a lot on my last record, that I put out. The blend between her and me and Emmy was just really magical! So we’ve done some stuff together, the three of us.

“But what Emmy and I wanted to do was just explore. See what we could go find out there. We wanted to push the limits a little bit, and see what we could find in terms of texture, combining styles, of things that we liked that don’t always fit in one little (category). Like the McGarrigle Sisters. Where do you put that? It’s not really traditional folk music, and it’s got traditional roots. It certainly isn’t bluegrass. And the sentiment is too unbridled for current pop, ‘cool’ standards. But it’s very intelligent music.

“There’s other stuff that is kind of like that; that’s kind of ‘out there.’ And there’s some stuff that’s just real, real traditional. So we’ve just been fooling around with various singers. And then I sang with Claire Lynch and my cousin John, who’s got a wonderful voice – on two songs.”

Although she maintains that after a project is finished she doesn’t care what happens, Ronstadt is intensely involved in its creation. “Oh, I mix everything! I do every single thing,” she declared. “I make the record, I do the arrangements, I do the harmony arrangements, I do a lot of the instrumental arrangements. Nothing is done on the record without me being there. But when it’s finished, I never listen to it again. You can take it and throw it off a cliff, for all I care. I’ve heard it and I’ve done it, and that’s the experience; and now I go on to something else. So at that point, I surrender it to the record company, and they do whatever. They can shoot it with a gun if they want to. I don’t care what they do. Long as they don’t shoot me.”

Returning to the topic of bluegrass, Ronstadt commented, “I understand what [the banjo] does, rhythmically. And I appreciate what it does – that syncopated thing; the difference in all those accents.

“I think of the banjo kinda like I think of the trumpet in mariachi, which is: trumpet was brought in about the same time that the resonator was added onto the back of the banjo. It was a ‘radio’ event, and a good one. It was a really good thing; it needed that high end to cut through. But if somebody came to bed and blew a trumpet in my ear, I’d get annoyed! If somebody came to bed with me and started plucking a banjo, I would probably jump right up to the ceiling! But it’s a great instrument in the orchestral blend. It’s really got a great place. And I don’t think the banjo will ever go out of style.

“Those other instruments are a lot more flexible. They can bear a lot more. I’ve really become a complete mandolin fan, ‘cause I’ve been working with David Grisman. I just think he’s a genius. I knew his playing. I knew he was considered a ‘hot chops’ player. I think he plays bluegrass sometimes, but he really predates and transcends all of that stuff completely. I mean, he can play like a classical player. I’ve never heard anybody with dynamics like that, and I’ve never played with anybody that could play with a vocalist; and play little internal harmonies. He just flits around like a little hummingbird – all around the vocal line – and plays a beautiful little harmony for a while, and then he goes off to a rhythm pattern, then he comes back. He has great ideas for voicings, and he has very, very good rhythm ideas. I just love to work with him. I think he’s brilliant.

“You know what I think is missing from bluegrass at this point? And from all that kind of traditional music? Dancing. That’s what I discovered with Mexican music, was that it is dance music. Period. I think, as is fiddle (music). As soon as you uncouple it from (dancing), the music changes. It’s the same way with pop music. As soon as it became recorded music – people started dancing in discos to recorded music – the music stopped being alive, and it stopped changing in a real vital way. Started changing in a more static, strange, mechanized way.

“So my suggestion, to the bluegrass world would be, one should never uncouple that music from dancing. There should always be dancers involved with bluegrass music.”

The author commented that singing is also something that’s been taken away from most people and given only to professionals. “Yeah, it’s an outrage! In Mexican culture, everyone sings,” she responded. “Everyone knows all the words, and they all sing. We sing at the dinner table. Whatever you’re doing, you sing. You sing in a funeral, you sing at a birthday, you sing at a wedding. You sing if you’re happy, you sing if you’re sad. It’s a thing you get to do to help you along with your life. Everyone should sing. It’s a biological necessity. Even little babies sing. I mean, even when they’re pre-verbal, you hear them kind of leaning into a sound.”

(Read part one of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

Photos and artwork courtesy of Shore Fire Media

Article appears courtesy of Bluegrass Unlimited

Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass (Part 1 of 2)

Barely three minutes into the brand new documentary, Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, the viewer is already presented with none other than Dolly Parton, who exclaims, “Linda could literally sing anything.”

Over the course of her singular, era-defining career Ronstadt did sing almost anything — from The Pirates of Penzance to American standards to Mexican folk songs — but she’s rarely referenced in the same breath as bluegrass. The BGS x Linda Ronstadt history notwithstanding, it’s understanding that the twain rarely meet, in conversation and consideration. Of her most easily recognizable hits, among them “Willin’,” “You’re No Good,” and “Desperado,” perhaps “Blue Bayou” is the closest to bluegrass — and in its Ronstadt iteration, less so than in other covers of the languid ballad.

Scratch the surface, though, no matter how slightly, and her bluegrass cred runs deep. This should come as no surprise, given her immaculate performances alongside Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris on Trio and Trio II — the first song the three sang together, informally, at Harris’s house in L.A. was “Bury Me Beneath the Willow.” The Sound of My Voice digs a little deeper still, reminding that Ronstadt’s very first hit, “Different Drum,” recorded with folk-rock trio the Stone Poneys, was discovered by Ronstadt, who first heard the song from a now almost-forgotten bluegrass band, the Greenbriar Boys.

Elsewhere in the film, Ronstadt mentions that during her early days in the city she frequented Los Angeles’ The Ash Grove, the foremost folk and bluegrass venue there in the ‘60s and ‘70s. She also made appearances and recorded with the Seldom Scene, and remained close friends and musical confidantes with John Starling. One of the last studio recordings Ronstadt ever released was a duet of the Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard classic, “Pretty Bird” with bluegrass legend Laurie Lewis. The track was released on Ronstadt’s Duets project as well as Lewis’s The Hazel and Alice Sessions and the pair worked together prior, as well, performing as “The Bluebirds” with Maria Muldaur at Wintergrass Music Festival in 2005.

The bluegrass tendrils are there, undeniably, woven alongside so many other influences and inspirations and impressions that informed Ronstadt’s art. Still, it was surprising to this writer to find that in June 1996 Bluegrass Unlimited, the foremost and longest-running print publication dedicated solely to bluegrass music, had featured a lengthy, in-depth interview with Linda Ronstadt herself. Even by author Dan Mazer’s own admission, “Ms. Ronstadt’s bluegrass/country connection is tenuous at best.” And yet, for nearly five thousand words, the article displays that Ronstadt isn’t just tangentially connected to bluegrass, it is a permanent part of her musical self.

In honor of the new documentary film, and in appreciation of this connection to bluegrass — and in an attempt to shout it from the proverbial rooftops! — we’re reprinting Dan Mazer’s interview with Ronstadt exactly how it appeared in 1996, split into two parts, but in its entirety on BGS. Special thanks to the team at Bluegrass Unlimited for partnering with BGS to spotlight how bluegrass has touched one of the most important and truly iconic voices to ever grace this planet. — Justin Hiltner, BGS Associate Editor

(Read part two of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

“Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass”

By Dan Mazer. Bluegrass Unlimited, June 1996

While preparing an article on the influence of bluegrass on today’s country music, I had the opportunity to interview several prominent country stars. During discussions with Bluegrass Unlimited’s editorial staff about artists to interview, the name Linda Ronstadt came up.

Linda Ronstadt? It seemed an odd choice at first. Ms. Ronstadt has had a long and varied career, and while her forays into bluegrass with the Seldom Scene have been recognized and celebrated within the bluegrass community, as an artist, she just didn’t seem to fit in with the likes of Marty Stuart, Hal Ketchum, and Patty Loveless. On the other hand, her classic recordings of “Blue Bayou,” “Silver Threads and Golden Needles” and “When Will I Be Loved?” are still copied by country music cover bands some 20 years after their release. Some of her work as also been covered by bluegrass artists.

Because Ms. Ronstadt’s bluegrass/country connection is tenuous at best (especially in recent years, when her recordings have featured opera, Big Band and Mexican music), it was with little hope that I sent an interview request to Ms. Ronstadt’s publicist. To my surprise and delight, the request as answered quickly with a call from the publicist to set an appointment for a telephone interview. Ms. Ronstadt called me from her home in Los Angeles, and graciously granted me a significantly longer interview than we had arranged – that was just because the conversation was so interesting and enjoyable! She is remarkably well-spoken, intelligent and passionate. In the end, we decided not to include Ms. Ronstadt’s remarks in the profile of country artists with bluegrass roots.

Ms. Ronstadt grew up in Tuscon, Ariz. Her family listened to a broad variety of music on the radio. Opera, country, rock ‘n’ roll, and jazz filled the house. Some radio shows also featured bluegrass. “We were right in the pat of XERF, Del Rio, Tex,” she said. “And we (had) the Louisiana Hayride. We were right there, where there was a lot of big transmitters, and not a lot of interference. So I heard (bluegrass) when I was little, growing up.

“When we were kids just listening to stuff on the radio, we tried to sing it. My brother and sister and I could always harmonize real early. So we used to sing the stuff we heard on the radio. We heard Bill Monroe, and we heard Flatt and Scruggs, we heard Homer and Jethro doing a sendup of ‘Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes.’ I had such a cross-section! And then, when I was in high school, I think it really intensified.

“I’ve always been interested in harmony. I’ve always been a harmony singer. When I was a real little child, I could sing harmony. I’m always surprised when children say, when they’re three, that they can’t. But all my brothers and sisters could, real early. I could hear strange harmonies, too. But I understood Mexican harmonies better, and they have a tendency to be very, very clear kind of parallel thirds.”

(Author’s Note: “Parallel thirds” refers to what, in bluegrass, corresponds to the lead and tenor part singing close harmony at the interval called a “third.” Brother duets also feature this harmony.)

As an artist, Ronstadt doesn’t feel authentically connected to bluegrass. “I feel that I would have had to live in the rural south, and grow up in the mountains,” she said. “There’s just such a difference between mountain South and plantation South. Culturally and musically.”

Since she grew up near the Mexican border, and her father is Mexican, Ronstadt mostly sang Mexican music as a child. “There’s a great deal of similarities (between bluegrass and Mexican music),” she noted. “One of them is that the three-part harmony stuff that we sang a lot is Mexican mountain music, and it’s country music. The music of an agrarian lifestyle is what I’ve always been most attracted to. I love it, and having grown up in a kind of isolated, rural setting, it was something that reflected what I was witnessing around me.

“I’ve always had an ear for any kind of a thrilling, wild, high tenor. And again, in Mexican music, there’s a loose parallel, especially up in the mountains, where they sing real high in this falsetto, in the huapango style.

“The language and the pronunciation of the language – whatever the rural accent is – influences the style of singing and the vocal intonation so profoundly! With bluegrass music it was those ways of pronouncing 16th Century English, probably, frozen in those mountains. But in Mexico, of course, it was the indigenous language of nahuatl, which was what was mostly spoken there, which gave the pronunciation and forced the tonality into that nasal thing.

“Also, having to communicate across long distances, you get a real high, ringing (tone). Men get a lot of power out of that high register; way more than women do, which is why – having absolutely nothing to do with sexism –I feel that bluegrass is very wonderful when it’s three male voices. Mariachi music, also (is an example), which is from a different region (Jalisco). But when all those male voices are singing up in the high register, it’s a different sound from a woman’s voice singing up in a more comfortable register. I can sing bluegrass tenor pretty well, but it doesn’t quite have the power that it will ever have from a man forcing himself up way high in that register. It just doesn’t have the same dynamic. It’s still good. I call it ‘pink grass.’”

Until recently, bluegrass has been almost entirely a male reserve. Ronstadt feels that there is good reason for that, although, as she pointed out, “There was old-time music before that, which of course, happily embraced women singers. But I still think it was just that thrilling sound of those male voices in two- and three-part harmony, pushed way, way up high, that really gave it a very distinctive characteristic. And it’s pretty hard to compromise that, regardless of your sexual politics, without making it into something different.

“There are women singers today that have what I think (are) very, very good, and very authentic-sounding bluegrass voices. I think Claire Lynch has a wonderful voice. I love her singing! And those girls that sing with Alison Krauss; the Cox Family. But it’s hard to say. Where do you draw the line? Is that bluegrass, or is that old-time? I think that’s a combination; both things.”

When thinking of acts that embrace and also expand bluegrass, the Seldom Scene immediately comes to mind. Many people argue with some justification that the inclusion of a banjo defines an act as a bluegrass band. Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, Reno and Smiley and the Stanley Brothers all performed certain songs (usually gospel numbers) without the banjo, but the Seldom Scene broke new ground with their unprecedented, mellow guitar-based sound. Furthermore, because Ben Eldridge’s banjo playing is unparalleled for taste and restraint, the Seldom Scene can be mellow even on tunes that include the banjo. They also distinguished themselves by using Linda Ronstadt as a backup vocalist on some of their earlier recordings. They remain her favorite bluegrass band.

“They really are an urban band with very, very strong rural influences,” she said. “They had all the benefit of a sophisticated, cosmopolitan atmosphere, which Washington, D.C., certainly is, and they were able to refine in any direction they wanted to. I really think they made an extraordinary synthesis. I love that band; I always have.

“Mike (Auldridge) is such a unique player. Nobody sounds like him. He’s got that real beautiful, lyrical, velvet thing that happens, but it’s still got plenty of strength and guts behind it. There are more famous Dobro [resonator guitar] players than that, but I like him the best and I always call him when I want a Dobro [resonator guitar] player.

“John Starling is an exceptional singer, and has a wonderful sense of the groove. He’s a very, very fine guitar player. Emmylou Harris and I both spent so many hours and hours and nights and nights and months and months with him, way on into the night, just grooving on that sound and exploring it! He’s given us a wealth of something. It’s hard to define. But just having that superb musicianship to lean on, and the focus of his sensibility, which is very keen and very well-developed in that direction.

“I remember getting snowed in at John Starling’s house with Lowell George, and Emmy, and Ricky Skaggs (in 1974 or 1975). Fayssoux Starling was there, who was a good singer. And we sang forever! I mean, we sang all night, and they were there for three days. I was sick, so i was there for a month, they were there for three days, and in that time, Ricky Skaggs taught me a whole lot about how to sing bluegrass harmony. I knew a little bit about it, but he really showed me how the suspensions worked, and it helped me to refine it a lot. I understood (the suspensions), but didn’t know quite how to really imply them. He Walked me through ‘em, and after that, I had ‘em.”

(Author’s Note: “Suspensions” is a musical term referring to creating tension in a chord by sounding a not that is not in the chord, and then releasing that tension by lowering the dissonant note. For example, a guitarist will sometimes play a “D” chord and add a high “G” note on the third fret of the first string for one measure, then release that fret, so that the “F#” note rings.)

Ronstadt is surprised that she is sometimes cited within country music. “I was never a country singer,” she stated. “I never thought of myself as a country singer. Always very surprised if anybody else did. I was a pop music singer, and I used various root forms that were acceptable to me, and that was one of the things that was readily acceptable to me.

“I’ve always had a little rule about my singing. If it wasn’t there in the living room by the time I was eight years old, it generally won’t be very successful if I take a swing at it, at least to my standards. But thanks to the radio, there was a lot of stuff in play by the time I was eight. And thanks to the fact that my family has very eclectic kind of taste, anyway.

“So, when I came into pop music, I played songs that I loved. I didn’t care whether they were written by George Gershwin or Hank Williams. A song that would really inspire me for one reason or another, I’d try to sing it. And I’d always try to put it into its appropriate setting. So if it (was) a bluegrass song, I’d try to put it in that kind of setting, and I knew enough about the mechanics of how it worked, so that I would do that. Then there were these singers and players that I really admired, and tried to emulate. But that thrilling high tenor sound, there’s just nothing like it.”

The closest Ronstadt has come to recording bluegrass in recent years was on the “Trio” album, which featured her along with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris. A follow-up recording was eagerly anticipated, but never materialized. “The ‘Trio’ record became so difficult, schedule-wise, that we all gave up,” she said. “But Emmy and I did quite a lot of singing together. We had a great time! See, Emmy and I started out with this idea to do a record together, where we would use some guest artists. And we sort of progressed down that road, but it never got to where everybody would agree on a release date. Everybody did agree at some point, but the people kept changin’ their minds.

“But Emmy and I really are kind of locked on to each other musically. Emmy and I have sung some stuff together that’s gonna be on my record; Emmy and I have sung some stuff together that’s gonna be on her record. And we also did some stuff with Valerie Carter, who’s just a great singer.”

Ronstadt’s bluegrass influence is definitely shown in her current release.

(Read part two of “Linda Ronstadt Talks Bluegrass” here.)

Photos courtesy of Shore Fire Media

Article appears courtesy of Bluegrass Unlimited

MIXTAPE: Eric Corne’s California Country

California country has deep roots and an enduring influence. It’s given us the Bakersfield Sound, country-rock, cosmic country, cow punk, and much more. I love the more raw/less polished sound and how its artists tend to chart their own course. Nashville was a company town; California was where the mavericks went. I have a strong personal connection to California country, stemming from my work as Dusty Wakeman’s engineer at Mad Dog Studios in Los Angeles. Dusty played bass with Buck Owens, engineered Dwight Yoakam’s seminal albums, and co-produced Lucinda Williams’ first two albums. There’s still a strong core of musicians in L.A. with roots stretching back to these earlier generations, and it’s a thrill and an honor to be writing and producing records with such soulful and beautiful people, many of whom populate the selections below. — Eric Corne

Buck Owens — “Streets of Bakersfield”

Buck Owens is, of course, a pillar of California country and a pioneer of the Bakersfield Sound. An iconic harmony guitar riff provides the instrumental theme, with gorgeous vocal harmonies and pedal steel lifting the choruses. This song really encapsulates what California country represents to me — the desire to be oneself.

Merle Haggard — “Working Man”

This is one of my favorite Merle songs. It’s got a great groove and terrific guitar playing with lyrics that clearly represent the blue-collar ethic he embodied.

Lucinda Williams — “Sweet Ole World”

Lucinda really helped broaden the boundaries of country just by doing her own thing. This song has an angelic vocal melody with beautiful harmony and precise responses from the guitar. Immaculately recorded and co-produced by my mentor Dusty Wakeman.

Dwight Yoakam — “It Only Hurts When I Cry”

Dwight and Pete Anderson were real students of classic country music, especially the Bakersfield Sound, and they were at the center of the cow punk movement, along with X, Lone Justice, and others. This is a great song with witty lyrics, perfect production, and top-notch performances.

Jean Shepard — “If Teardrops Were Silver”

Raised in Bakersfield, Jean Shepard was a pioneer for female country singers and one of its first great stars, following on the heels of Kitty Wells’ breakthrough. She had a really pure voice with a lovely vibrato and a great ability to interpret a song.

Bob Wills — “Bubbles in My Beer”

It could be argued that Bob Wills is the godfather of the Bakersfield Sound. He played there regularly and had a strong influence on both Buck and Merle … something I can really hear in this song.

Sam Morrow — “Skinny Elvis” (Featuring Jaime Wyatt)

I’m really proud to work with these two brilliant, young, California country artists who are getting well-deserved national attention. I wrote this one for Sam’s album, Concrete and Mud. It’s a little reminiscent of the Gram/Emmylou song “Ooh, Las Vegas,” so I thought it’d make a great duet with Jaime. I recruited legendary Gram Parsons/Byrds pedal steel player Jay Dee Maness to play on it, which was quite a thrill, as you can imagine.

Guy Clark — “L.A. Freeway”

Guy Clark wasn’t in L.A. for long, and this song is about leaving, but it’s a beautiful farewell song. The song makes reference to another beloved and iconic figure of California country — “Skinny” Dennis Sanchez who played bass with Clark, and ran in circles with the likes of Townes Van Zandt, Rodney Crowell, and Steve Earle. There’s also a thriving honkytonk in Brooklyn named after him. It’s an incredible performance, very dynamic, with a sympathetic arrangement including Wurlitzer piano, weepy fiddle, moaning harmonica, and gorgeous chorus harmonies.

Jade Jackson — “Motorcycle”

Here’s another great, young country singer coming out of Cali right now. I love this lyric and vocal performance — intimate with a dark, rebellious under current.

Linda Ronstadt — “Silver Threads and Golden Needles”

Her early career country records are really underrated. This is a killer country-rock version of a Dick Reynolds/Jack Rhodes classic song with strong ties to the Flying Burrito Brothers. I think Ronstadt is also important to include here, due to her work with Neil Young, the Eagles, Jackson Browne, and others in the L.A. country scene of the late ’60s and early ’70s.

The Byrds — “Hickory Wind”

No playlist of California country would be complete without a song from the Byrds’ seminal country album Sweetheart of the Rodeo. My first gig in Los Angeles was assisting Dusty Wakeman on the mixes for the Gram Parsons tribute concert at which Keith Richards did a beautiful heartfelt version of this song by his old pal, Gram.

Sam Outlaw — “Jesus Take the Wheel (And Drive Me to a Bar)”

An instant classic by one of the brightest stars of the current generation of California country singers with outstanding production by Ry Cooder and Bo Koster of My Morning Jacket on keys, who also guests on my new record.

The Flying Burrito Brothers — “Hot Burrito #1”

Even though Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman’s importance is already represented here via the Byrds, I wanted to include this achingly beautiful Burrito song, partly because of Gram’s incredible vocal and melody, and partly due to Bernie Leadon and the link he represented as a member of both the Burritos and the Eagles, the latter heavily influenced by the former.

Gene Autry — “Mexicali Rose”

Gene Autry’s singing cowboy films were instrumental in bringing country music to a national audience in the 1940s. I was very fortunate to record Glen Campbell on his version of “Mexicali Rose,” but thought I’d include Autry’s version here.

Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young — “Helpless”

I think the Laurel Canyon music scene played an important role in California country and Neil Young, in particular — first with Buffalo Springfield, with songs like “Learning to Fly” and “I Am a Child,” and later with his Nashville-recorded classic, Harvest. “Helpless” to me represents the seeds of Harvest.

Eagles — “Tequila Sunrise”

Not much needs to be said about the first two Eagles’ albums and their role in the popularity of country-rock. Not to include them would seem an oversight. This also represents the beginning of the fruitful Glenn Frey/Don Henley songwriting partnership.

Squared Roots: Tift Merritt on the Fearlessness of Linda Ronstadt

In the world of folk-rock, a few artists reap the lion’s share of mentions, with Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, and Jackson Browne, among them. One of the great voices of the genre, though, is Linda Ronstadt. As a singer and song collector, she is all but unrivaled — a point most of her peers would agree with. Starting in the mid-1960s as a member of the Stone Poneys and, later, as a solo artist, Ronstadt made a name for herself on the marquees of folk clubs and rock arenas, alike, thanks to albums like Hand Sown … Home Grown (which some consider the first alt-country album by a female), Silk Purse, Heart Like a Wheel, and many more. Her artistry recognized no boundaries as she recorded with the Nelson Riddle Orchestra, as part of Trio with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris, and in Spanish. In 2011, however, she announced her retirement brought on by a battle with Parkinson’s disease.

“I don’t have any great, huge proclamations to begin with, except that I adore Linda Ronstadt,” singer/songwriter Tift Merritt says with a laugh. And, really, that’s enough. From her debut album, Bramble Rose, to her latest release, Stitch of the World, Merritt has attempted to follow in the footsteps of her musical heroes — women like Harris and Ronstadt — who have blazed a trail of feminine fearlessness. By pretty much all accounts, she has succeeded — a point most of her peers would agree with.

Are you a student of Linda’s work for your own artistry or just a fan for your own enjoyment?

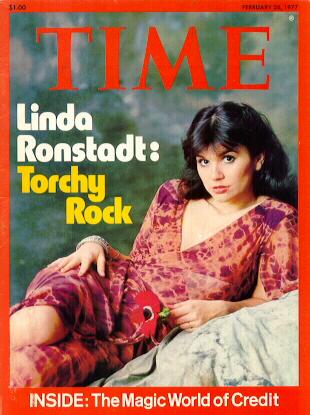

You know, I wanted to talk about Linda because she’s not singing anymore because she has Parkinson’s, so it’s almost more important to talk about her now because of that. I think what we need to talk about with Linda Ronstadt is that, at the height of the singer/songwriter movement, she was the one headlining stadiums with the Eagles and Elton John. I think it’s really important to talk about a woman doing that. She was bringing all these songwriters she knew and loved, and taking their songs and singing them. She was on the cover of Time magazine. She was a girl next door and a member of the band with a very understated sexuality, but she was also an absolute star and a commercial success. I think we tend to think about women with guitars singing earthy rock ‘n’ roll as coffee shop acts or something that’s going to fall apart in your hands. And Linda Ronstadt was kicking everyone’s ass. [Laughs]

[Laughs] What’s interesting is that there’s a quote of hers from 1999, in which she said, “I always mean to be a singer, not a star.” So, even though she achieved that level, like you said, it wasn’t necessarily her goal.

I think that’s why it’s important to talk about, too. Because she is an artist. I think she had a complicated relationship with her success and how she was viewed, sexually, and all of that. But she achieved success through her art. And I know that I first fell in love with Linda Ronstadt records when I was in my early 20s. In fact, when I made Bramble Rose, I wanted to make a record like [Emmylou Harris’s] Quarter Moon in a Ten Cent Town or I wanted to make a record like Heart Like a Wheel or Silk Purse or one of the early Bonnie Raitt records. Those first records were so raw and heartfelt and just penetrated your bones and brought tears to your eyes.

I remember that was said in the press release for my first record, and one of my first reviews kind of made fun of me for liking Linda Ronstadt. I thought, “Oh my God. This person doesn’t get it.” For me, all of those women, and Linda Ronstadt, especially … this was in the late ’90s or early 2000s. I sort of came of age in the ’90s. Madonna was on MTV in the ’80s. And I needed some female role modes who were more like me, who had something to say, who were not intent on acting outrageously, but really wanted to be storytellers. And who had a lot to say and who were masters of their art. You can tell from Linda Ronstadt’s discography and her work as a writer and a singer, she’s a student of her craft. But she always manages to look so cool in all the pictures of her! And she was in a band, too! You navigate this world of dudes traveling on the road, and she did that with so much grace.

Yeah. Yeah. I feel like, in listening to her and reading about her, to me, her fearlessness as a singer …

Uh huh. Absolutely!

… both in song choices and vocal delivery. You can hear so much in her voice.

She’s totally fearless. Maybe that’s the source of her power because she’s so powerful, as well. I’ve sung along with those records … I had a break up and I ended up putting on those records to comfort myself and I was right back there. I’ve been singing along to those records for such a long time, and her voice is an unbelievable instrument. Unbelievable. It’s silken and velvet, and also as powerful as steel. And it’s fierce. The effortlessness with which she can belt at the top of her range, then go low … any melody is so lucky to end up in her hands. [Laughs]

[Laughs] What does it take for a singer to do what she did — both in terms of breaking down as many genre barriers as she did and finding her way into songs she didn’t write, but might as well have? They sounded like they were fully coming from her.

Right. They were realized through her. I don’t know her, personally, at all. But my impression is that it’s a combination of open-heartedness and intelligence and that fearlessness where you are singing with your heart on the line. Period.

Yeah. You find your way in and bring everybody along with you.

Mmm-hmm.

The other thing I feel like … her identification as a singer and, later, a producer … she was no less revered and respected just because she wasn’t a songwriter.

No. I know.

Except for with the guy who reviewed your record. [Laughs] Do you think that’s changed at all? These days, is being a songwriter, too, a huge part of the credibility factor?

I don’t know. I think the world has room for so many different types of careers. I come at this as a writer. But music is such a powerful thing, and to be able to inhabit that … music is a physical and social medium. To be open enough to let that run through you, it’s really an awesome thing.

I took some time off from touring and I missed that. It’s such a joyful letting go, even if it’s a sad song. And I think that’s what you hear when you listen to Linda Ronstadt. So much power coming through these tiny muscles in your neck. They’re so fragile. They’re the size of a dime. There’s an electric current that seems to jump out of her. Like a river of feeling coming out. I think it’s important to talk about, that music is not about a canvas on a wall. It’s not about words on a page. It is a physical, living, breathing type of media. And to be able to do that seamlessly … I love watching and hearing people who have that gift. And it is a gift.

That’s a great ending, right there.

Well, we just have to mention that “Long Long Time” and “Blue Bayou” are two of the greatest performances of great songs. Ever. [Laughs] That is all.

Tift Merritt photo courtesy of the artist. Linda Ronstadt photo courtesy of Carl Lender.

Linda Ronstadt: Hasten Down the Wind

In Home Free, his 1977 novel of faded denim hippie dreams, Dan Wakefield described his wandering anti-hero Gene Barrett overhearing a song on a nearby record player as he dozes in a hammock in Maine — Linda Ronstadt singing her folkish country ballad “Long Long Time” in the alto that wafted through many a window in those imperfect, exploratory days. “Gene was glad it was Linda Ronstadt, not someone soppy or sickly sweet,” Wakefield wrote. “Strong. Gutsy. Belting it out. Her voice didn’t seem just to come from the house, but out of the earth, over the water into the rickety little town and the scrubland and forest beyond it.”

Beginning in the 1970s, Linda Ronstadt’s singing has had that kind of geological effect throughout popular music: steadying, seemingly able to erase time and trends within one flow of feeling that goes below the surface and the deeper strata of American consciousness. In a time of fading utopian hopes, she emerged as an emissary able to connect old musical ways with the new consciousness of her own maverick generation. “She is offering us something very valuable for the '70s: not a fantasy figure, but a reality figure,” wrote the rock scribe Tom Nolan in 1974. Raised on country and the ranchera music that echoed through her Tuscon, Arizona, neighborhood, Ronstadt sang with a verve and directness that eradicated the pretentiousness that could sometimes afflict the children of the counterculture. Album titles like Hand Sown…Home Grown, Simple Dreams, and Hasten Down the Wind celebrated a naturalness that was complemented by a meticulous attention to musical detail and one of the greatest ears of the rock era.

Those who underestimate Ronstadt as a pretty face and voice who rose to fame on the power of others’ songwriting and production talents — and there have been far too many in that camp — are ignorant. From her teenage days in the folk trio the Stone Poneys, Ronstadt developed a persona that spoke profoundly to women waking up to the way many men had condescended to them throughout the early years of the supposed sexual revolution. She was an everywoman who, instead of building a world through songwriting, did so by taking on others’ words and melodies and reshaping them with intelligence and boundless energy. She grew up in public through her recordings. In 1971, when she was 25, she told a reporter that she didn’t have the voice to do soul music; by 1974, she’d developed her own style of testifying that made her funky reinterpretation of Dee Dee Warwick’s 1963 shouter “You’re No Good” into a number one hit, one she’d follow up by reinvigorating songs by Martha and the Vandellas, Chuck Berry, Roy Orbison, and the Everly Brothers, among others. At the same time, she continued championing her own peers, who played on her most successful albums. She was that woman who, like so many others, did the real power lifting within a scene dominated by self-styled heroic men.

When the multi-platinum success of her fifth album, Heart Like a Wheel, sent Ronstadt into the arena-rock stratosphere, she became the premium interpreter of an American songbook that she’s continued to redefine throughout her career. It now includes everything from George Gershwin and Cole Porter to early rock 'n' roll, the Nashville sound, Mexican canciones, Laurel Canyon balladry, Cajun two-steps, and the punkish sounds of New Wave. She developed her singular eclecticism, in part, as a way of coping with a music industry that would have kept her in a stadium-sized box — she hated playing those big venues, ripping up her voice in front of anonymous-feeling hordes — and turned to theater music and standards as a way of reclaiming her right to be a subtle interpreter. "Your musical soul is like facets of a jewel, and you stick out one facet at a time," she said in a retrospective interview in 2003.

Even as a teenager, when lesser musical adventurers would fall into a rut, Ronstadt would change course. Setting forth on a solo career after early success with the Stone Poneys trio challenged the boundaries of strummable folk music by foregrounding its connections to country and becoming as much an inventor of country rock as was Gram Parsons or the Eagles, who famously formed as her backing band. After finding a niche as the patron of her L.A. neighbors, from Warren Zevon to Randy Newman and Jackson Browne, she teamed up with producer Peter Asher to hone that rocked-up pop sound that made her a superstar. Throughout her career, she would return to that sound which, in turn, became hugely influential, forming part of the bedrock of many future stars’ styles, from Olivia Newton-John to Sheryl Crow to Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and Carrie Underwood.

Meanwhile, Ronstadt became a producer herself, an extension, in some ways, of her role as a brilliant collaborator. Her work behind the boards with the soul legend Aaron Neville, for example, complements her many beautiful duets with him. Her deep love of harmony singing, along with her dedication to uplifting the women with whom she feels the deepest musical kinship, led her to form one of the most beloved vocal groups in recent pop memory — Trio, her project with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris. “I always mean to be a singer, not a star,” she said when the second Trio album was released in 1999. In fact, Ronstadt’s stardom has been predicated upon her ability to consistently remind listeners that to sing is to cultivate a space where all the trappings of the moment — fashion, fame — fall away, a space of pure joy and sensual release.

Linda Ronstadt can no longer call that space into being in real time, having lost her voice to Parkinson’s disease in 2013. But she remains a bright spirit: the author of a revelatory book, Simple Dreams: A Musical Memoir, and a role model for a new generation of musical boundary breakers. And through her immortal recordings, her voice still permeates the soil of our consciousness, a clear liquid presence easing our minds and, by example, urging us to continue challenging ourselves. A natural gift beautifully cultivated, Linda Ronstadt’s legacy still challenges us to be more free, even as it hastens down the wind.

Ann Powers is critic and correspondent for NPR Music and the author of several books, including Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music, forthcoming from Dey Street Books in 2017.

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.

BGS Class of 2016: Six of the Year’s Best Reissues

ICYMI, 2016 was a great year for new roots music — go check out our BGS Class of 2016: Albums feature, if you need some convincin'. We were introduced to Courtney Marie Andrews, gifted with a solo album from Amanda Shires, floored by Brandy Clark's sophomore solo effort, and so very much more. Lucky for us, 2016 was also a big year for roots reissues, so those of you playing along at home who have more of a "get off my lawn" approach to listening to music have plenty to be happy about, too. And we've rounded up a handful of this year's reissues that we can't stop spinning.

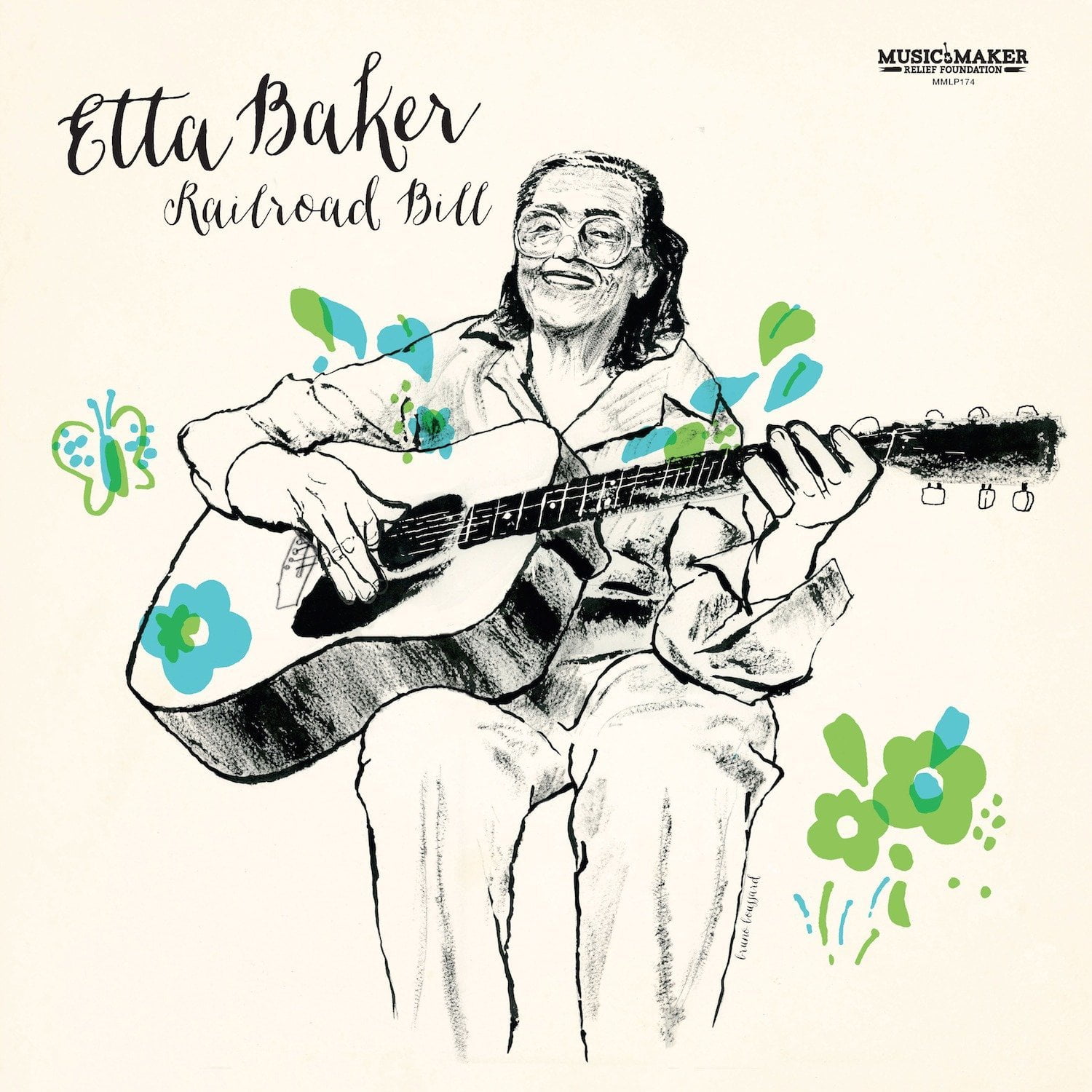

Etta Baker, Railroad Bill

It's no secret that we at the BGS love Music Maker Relief Foundation, a North Carolina-based nonprofit dedicated to preserving Southern music. One of the many wonderful things they did in 2016 was reissuing Etta Baker's excellent Railroad Bill on vinyl. If experiencing Baker's take on Woody Guthrie's "Going Down the Road Feeling Bad" in all its analog glory isn't enough of a draw, perhaps the never-before-seen digital videos that accompany the piece are.

J.D. Crowe and the New South, 0044

One of the most beloved bluegrass albums of all time came from a band that was around for less than a year. That album, nicknamed 0044 after being assigned the number by label Rounder Records, was the sole project of J.D. Crowe and the New South, features musicians like Gordon Lightfoot and Rodney Crowell, and counted Alison Krauss and her band as fans. It was re-released as an expanded vinyl edition on Record Store Day in April. If you're interested in learning the history of this iconic release, Rounder Records founder Bill Nowlin wrote a three-part series about 0044 for us earlier this year. Check out Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

Trio, The Complete Trio Collection

Oh man, where do we even begin with this one. Dolly, Emmylou, AND Linda? On not one but TWO albums? With bonus demos and unreleased songs? We mere mortals don't deserve it, but we'll sure as hell take it.

Buck Owens and the Buckaroos, The Complete Capitol Singles: 1957-1966

This new collection from Omnivore pulls together 56 of the songs that made Buck Owens a legend, and packages them up all nice and remastered. A liner note introduction written by Dwight Yoakam is the icing on top of this sweet, twangy cake.

The New Kentucky Colonels, Live in Sweden 1973

This sought-after live album from the New Kentucky Colonels has been out of print since 1976, but now it's finally available, and with additional content, to boot. Some 26 tracks chronicle two nights in Stockholm — a big step up from the original LP's 14 songs.

Junior Kimbrough, Meet Me in the City

It was the year of the reissue for Fat Possum Records, who released 30 different blues titles to vinyl in 2016. One of those albums was Junior Kimbrough's Meet Me in the City, a compilation of some of the Mississippi bluesman's greatest tunes, released one year after he passed away from a heart attack at the age of 67 in 1998.

The Essential Linda Ronstadt Playlist

Linda Ronstadt is one of our most beloved artists here at the BGS, a timeless talent who defied genres and broke barriers throughout her 44-year career. Born in Tucson, Arizona in 1946, Ronstadt came from a long line of prominent Southwestern figures, growing up on a ranch with her parents and three siblings. She began her music career in the mid-1960s, fronting the Stone Poneys before striking out after a solo career of her own.

It didn’t take long for Ronstadt to find fame, earning Rolling Stone covers and Grammy Awards in the mid-’70s following the release of landmark albums like Heart Like a Wheel and Simple Dreams. She would go on to collaborate with a who’s-who of popular music across a number of genres, including Neil Young, Phillip Glass, and, as part of their “Trio” project, Emmylou Harris and Dolly Parton.

Ronstadt continued touring and releasing new music well into the 2000s, eventually announcing her retirement in 2011. In 2013, Ronstadt shared she had been living with Parkinson’s disease and was no longer able to sing or perform.

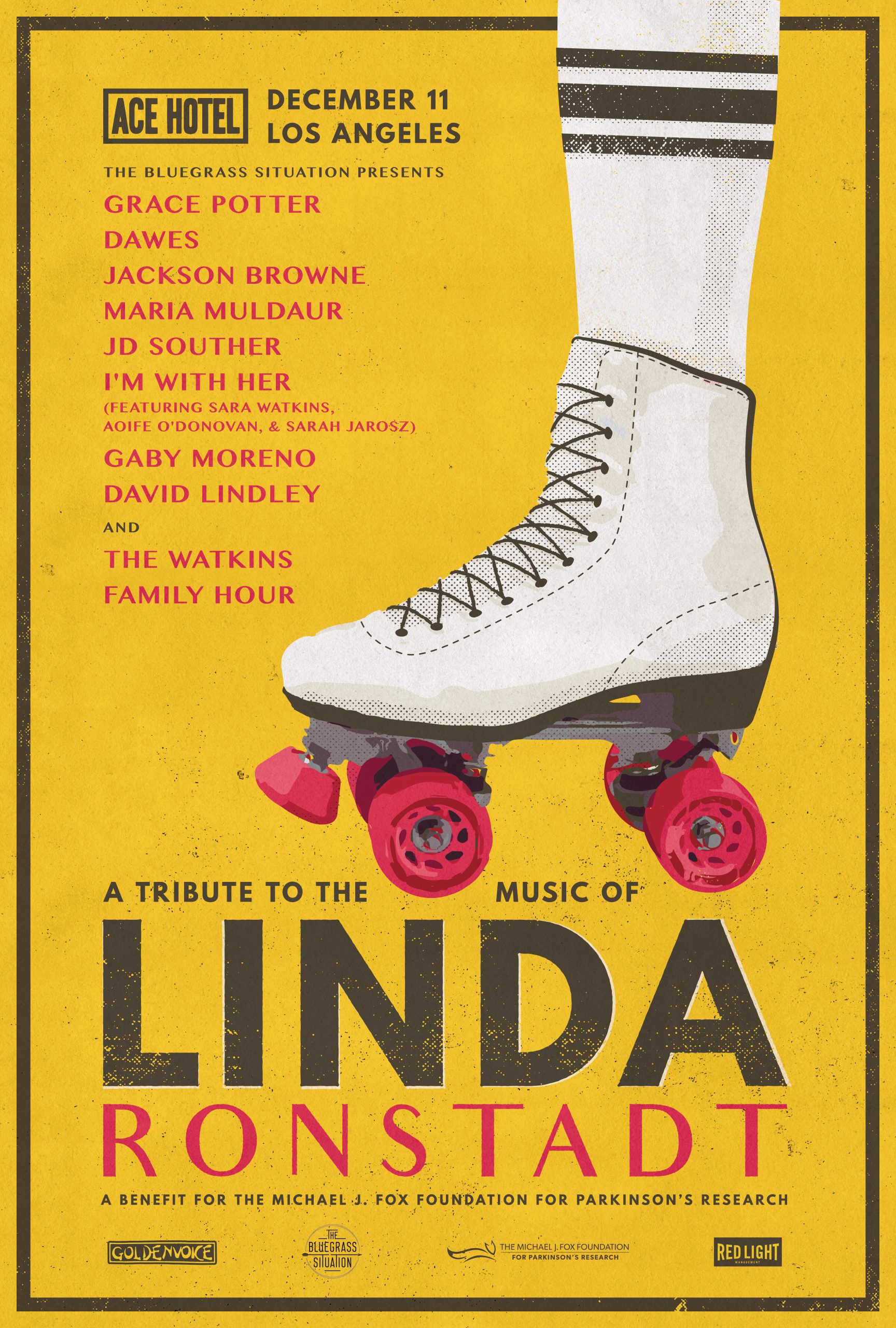

In advance of our December 11 BGS Presents show “A TRIBUTE TO THE MUSIC OF LINDA RONSTADT,” which features performances from Grace Potter, Dawes, Jackson Browne and more, we’ve put together a playlist of 20 songs from Ronstadt’s catalog we consider to be essential listening. If you haven’t purchased tickets for the show yet, act quickly as tickets — which benefit the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research — are going fast. Get them here, and, in the meantime, enjoy some of our favorite Ronstadt songs below.

Announcing the Bluegrass Situation Presents: A Tribute to the Music of Linda Ronstadt

We could not be more excited to to announce a one-of-a-kind event featuring Grace Potter, Jackson Browne, Dawes, Maria Muldaur, JD Souther, I’m With Her & more to celebrate the music of the legendary Linda Ronstadt.

‘The Bluegrass Situation Presents: A Tribute to the Music of Linda Ronstadt’ will take place at The Theatre at Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles on Sunday, December 11th at 8:00 p.m.

The show will feature performances by friends and colleagues of Linda including Jackson Browne, Maria Muldaur, JD Souther, and David Lindley, plus contemporary artists influenced by her musical legacy such as Grace Potter, Dawes, I’m With Her (Sara Watkins, Sarah Jarosz, Aoife O’Donovan), and Gaby Moreno, all led by the Watkins Family Hour house band featuring Sara & Sean Watkins. SiriusXMJim Ladd will also make a special appearance. Expect some very special surprise guests, and more acts to be announced closer to the event.

All proceeds will benefit The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Since 2000, the foundation has funded more than $650 million to speed a cure for Parkinson’s disease through an aggressive research agenda and the development of improved therapies for those living with Parkinson’s today.

“In a time when fierce female artists rule the airwaves, and the blending and crossing of genres is now the norm, there’s one woman who helped start it all,” BGS Executive Director Amy Reitnouer says. “Linda Ronstadt is simply a legend, and we believe her music should be celebrated now, by the people who love and have been influenced by her most, while we can tell her directly.

“The Bluegrass Situation is all about connecting the dots between traditional and modern culture, and Linda’s long-running and multi-faceted career – be it in country twang, torchy rock, traditional trio harmonies, Latin heritage, or any combination thereof – has embodied this idea like no one else’s before or since.”

The event is a co-production of BGS, Goldenvoice, and Red Light Management.

“I used to dig through my parents record collection and gush over Linda Ronstadt records. I am so proud to be a part of this meaningful tribute. I remember listening to her and sensing she was not just a pretty gal singing great songs. I felt like she was speaking directly to me through the music, because it’s not only her voice – it’s her presence. She showed up at a time when the the world needed a proper WOMAN. She is forever woven into the fabric of Rock & Roll history and I can’t think of a better cause or a more worthy human to be honored in such a special way.”

-Grace Potter

“I’ve known Linda Ronstadt since 1966, and in these 50 years we’ve shared so much as Sisters in Music! It is heart-wrenching to think that this mysterious ailment known as Parkinson’s disease has robbed us of her gorgeous, enthralling voice, but I’m happy to report firsthand that it has done nothing to diminish her spirit and keen mind, and I marvel, deeply touched, by the incredible grace and courage with which she faces this challenge. I’m honored to participate in this celebration of Linda’s music, which will benefit the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research to speed a cure for Parkinson’s disease, which can’t come a moment too soon!”

-Maria Muldaur

Tickets go on sale Friday, October 14 via AXS. Special presale starting Wednesday, October 12 for all American Express card members. VIP & Super VIP packages will also be available.

Exclusive BGS pre-sale will be available beginning Wednesday, October 12 for all our newsletter subscribers. Sign up on our homepage now.