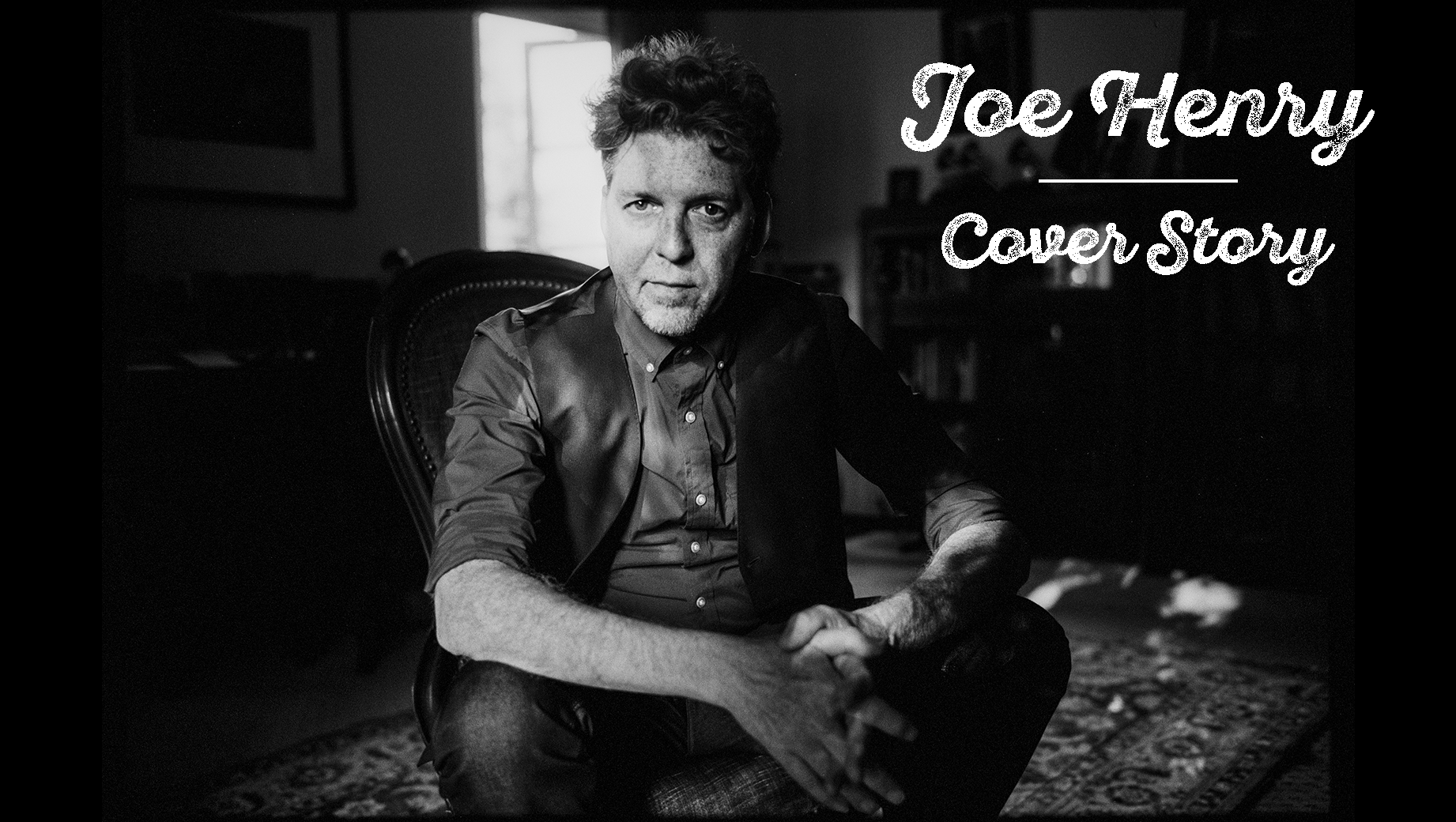

Volume 4 is a beginning and end for Kieran Kane & Rayna Gellert. It’s a beginning in that it’s the duo’s newest release, which means new songs, a new tour cycle, and a new round of interviews. It’s an end – “the end of an era,” as they put it – for Dead Reckoning Records, the label Kane and his bandmates in The Dead Reckoners launched 30 years ago. The independent venture grabbed the attention of other artists whose recordings they released, in addition to The Dead Reckoners’ first and only album, A Night of Reckoning, and the band members’ various other projects.

“Over the 30 years, [The Dead Reckoners] drifted into their own worlds, their own lanes,” says Kane. “Tammy Rogers and the late Mike Henderson started doing The SteelDrivers, Harry Stinson has been with Marty Stuart for years, and Kevin Welch is in Australia. For a long time, I was just putting out my solo records on the label, and then Rayna and I put our records out.

“30 years seemed like a nice, round, anniversary number to give everybody their work back, their masters back, and dissolve the company. It’s been great. I’m quite proud of the work we’ve done over the years and that it’s still a functioning label. We’ve managed to survive all kinds of digital flare-ups and breakthroughs and ways of sharing music. The company makes a little bit of money every year, but it seemed like, ‘Yeah, let’s call it a day.’ I called everyone and everybody was like, ‘That’s fine.’”

Bringing Dead Reckoning Records full circle is sweet rather than bittersweet, says Kane, “in that the label was started by an album of mine [Dead Rekoning, 1995] and thirty years later, on the same date [April 11], we released Volume 4. To me, it serves as bookends for the label.”

Gellert and Kane met at the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival in San Francisco. Their first collaboration was co-writing for Kane’s Unguarded Moments [2016] and Gellert’s Workin’s Too Hard [2017]. The following year, they released their first duo album, The Ledges, followed by When The Sun Goes Down [2019], and The Flowers That Bloom In Spring [2022]. This year brings Volume 4, which they produced, recorded, and mixed, with Kane on vocals and guitars, Gellert on vocals, guitar, and fiddle, and Kane’s son Lucas on drums.

I thought we’d start by introducing you to readers, but instead of telling us about yourselves, tell us about each other.

Rayna Gellert: Kieran is a multi-instrumentalist and songwriter with a long, awesome career doing all kinds of musical things ever since he was a child. The thing that other musicians immediately say about him is they comment on his sense of groove that seems to be a through line in his musical output. And he’s awesome. He’s the funnest person to write and perform with.

Kieran Kane: Musically, we are so much on the same path, and have been on the same path, for both our individual lines. But out of all the people that I’ve ever worked with, Rayna, in the same way she talks about groove when talking about me, I would have to say the same thing about her, in that it’s just so … I want to say reliable, and that sounds sort of pedestrian, but it is.

It’s like having a drummer and a bass player playing the fiddle, in that the pockets and the grooves are so strong and well established that I can drift away and they’re just there. And it’s all been unusually compatible in writing and playing and performing. We genuinely enjoy doing what we do together. It’s a lot of fun, and it’s creatively fulfilling, and all those things.

Rayna, in an interview with WYSO you mentioned there are differences in your songwriting processes. Could you tell us about those differences and how they work as a duo?

RG: Kieran’s the first person I’ve consistently co-written with. I mostly wrote on my own. I occasionally noodled around with a friend on something, but I had no consistent co-writer. I was very much a newbie to actual co-writing when Kieran and I started writing together.

He approaches songwriting from a completely different angle than I do and that makes it extra fun and adventurous. I’ve always started with some bit of lyric and melody that come at the same time together and I go from there. Kieran usually starts with some kind of instrumental riff that becomes the seed of a structure of something. Lyrics come later for him.

The combination of the way we come at a song is very compatible because it’s different. We bring different strengths to the table. I tend to be super verbose when it comes to lyrics. I spill a lot of stuff out, and he’s a great editor. He is really good at finding the key phrases, figuring out the hook, and creating a structure around that.

My background is in old-time music, so the idea of a long ballad where there’s no chorus and it’s just inspiration that goes on and on and on is totally normal to me. For Kieran, it’s like, “What’s the hook? What’s the chorus? What’s the instrumental riff that’s going to tie the thing together?” And it works together very well.

KK: I agree with that. A lot of times what I’m hearing, along with a song, is a record. So much of what we do is based on an intro, in a way, or, as she said, a little musical hook that’ll tie things down. I’ve almost never sat down with an idea about a song. It’s more like I sit down and start playing banjo or mandolin or guitar until something catches my ear and then a lyric will be a free association to get started.

With us, that’s true to some extent, as well. A lot of times we don’t know what the song is going to be about until we wade into the waters and go, “Oh, it could be this.” It seems to work. Whatever the two different approaches are, it comes together.

How is Volume 4 the next step in your journey? You’ve talked about the songwriting process. When it’s time to record, do the arrangements happen organically?

RG: His view of the song tends to be a little more zoomed out than mine. What he’s saying … he is not just thinking about the song, he’s thinking about the record – I think that’s about arrangement. That’s about, “How are the pieces fitting together here?”

It does evolve organically. We always have to decide, “What’s the instrumentation? What feels right for this? Am I playing guitar? Am I playing fiddle?” If he comes up with a riff on an instrument, usually it stays on that instrument. But we’re working with so few pieces that we make a lot of use of space, because that’s one of the biggest colors in our palette.

KK: A way for us to build things in terms of arrangements often – since, as Rayna said, there’s so few pieces – is to eliminate something, like, “We’ll drop out here, which will bring the song down,” because if we start off with the two of us singing and playing at the same time, there’s no place to go, other than to start removing things.

As I’m saying this, I realize that my mission, if there is such a thing, in writing and making records has always been about removing things, making it simpler, and cutting off all the fat, anything that’s unnecessary.

RG: One of the things that’s different about this project is, in a way, we approached the whole album sort of like we would approach a song, as in letting it be what it wanted to be.

On past albums, we approached it more like we were writing a set list for a show, where it’s, “Have we included different instrumentation? Do we have a balance of lead singers? Do we have uptempo and downtempo?” This album is structured more like the way we write a song, which is, “What does this want to be?” Regardless of instrumentation, regardless of who’s singing, regardless of whether we wrote the songs. It evolved into this little sonic package that feels like you go in there and it’s a room you hang out in for the length of the album. To me, that’s a different experience than our past records.

KK: I’ve never thought of it like that. Yeah. We’ve been writing a lot. We wrote three albums, I did an EP that we had written a couple of songs for, and Rayna did an EP that I helped out on a couple of songs and produced. So we’ve done a lot of work in the last eight years, or however it is, that we’ve been doing this. Before Volume 4, there were three albums and two EPs, which is a lot more work than I’ve ever done in that amount of time.

This record, to me, was a little bit more of a grab-back in a way. Rayna was talking about wanting to do a fiddle album at some point and I was like, “Let’s play more fiddle tunes.” So we did that and pulled some older songs that were, as Rayna was saying, “Let’s just do it.” In my mind, it’s almost cleansing in a way to have taken this “just let it be what it wants to be” approach. Now we can move on to something else … and I don’t know what that is.

Tell us about the recording process and gear choices on this album.

RG: We have a very simple home recording setup that we’ve refined over the years. We got some good mics that we like a lot a couple years ago, Soyuz mics. We use those for everything, for instruments and vocals, the same mics. We have four of those.

We have a Zoom R16 board that we can either record directly onto or use as an input into Logic for recording. It’s a very mobile rig. We spend our summers in the Adirondacks at a cabin and we do a lot of recording when we’re up there. Some of this album was recorded there and some of it was recorded here in Nashville, in our house. We can take the board with us and do a nice, clean, digital field recording.

KK: It’s a wonderful piece of gear and shockingly inexpensive. As far as instruments and things like that, this record is a departure for me in terms of guitars, because I’ve basically used the same Guild M-20 on every record and every show I’ve done with Rayna, and before that for the last twenty-five years. For some reason, on this record, I picked up a couple of different guitars that I’ve had lying around the house for years. It was like, “Let me try this song on this guitar. Oh, that’s fun.” Whether or not I would do that again, I don’t know, because the guitar I’ve used all those years I love and it’s so reliable.

There’s three different acoustic guitars for me on this record. One is a Martin 00-16 classic, an early-’60s gut-string guitar that I played on “Keep My Heart in Mind.” The other is an early-’60s D-28 that I played on “The Mansion Above.” The other guitar songs are all on the Guild M-20. Rayna played the same guitar that she’s been using, an early D-28.

Last year, I was listening to a lot of ’60s folk music. I was listening to Gordon Lightfoot, Ian & Sylvia, Bob Dylan, and things like that, and hearing these really simple guitars where there’s no real guitar solos or anything like that. “I Can’t Wait” fits into that mold – as does “Keep My Heart in Mind,” and “Imagine That” – in that there’s no solos, but there’s a repetitive musical vein that goes through it all. It’s just two people playing guitars and singing. It’s that simple, which is something that really appeals to me.

Is it accurate to say there’s a connecting thread of faith in some of these songs?

KK: Yeah, I think that maybe is a thread through it.

RG: Not from that specific angle, but we definitely talked about hoping that people, in listening to the album, felt comforted.

KK: “I Can’t Wait,” to me, is very much is about faith – not in a religious way, but in a general sense of hope. As bad as things are right now, I remain hopeful and I keep looking towards the light. I’m aware of the dark, profoundly aware of the dark, but I don’t think that’s the end. I think there’s light as well and there’ll be more light as time goes by.

There are a couple of songs, specifically “Whatcha Gonna Do About It” and “Short Con,” that people could easily interpret as political – and they are. There’s no doubt about that. “Short Con” we look at as written from the standpoint of the Constitution. It’s like, “Why don’t you believe in me now?” There are other songs we have that certainly people have told us, “We’re not interested in your political views.” There’s a few floating around that just turn out … it’s not like we sit down and try and write about politics, or faith, for that matter. It’s just where our mental space is at the time.

You can look at these new songs as being political, but we’ve started thinking about them as being patriotic. It’s patriotic to stand up and say, “No, you can’t do that. You can’t just pull someone out of their car and throw them in a jail in El Salvador or whatever.” That’s not a political statement to me and I think for us at this point, as much as it is a patriotic statement, it’s our duty as citizens to say something. We’re given that right and we’re taking advantage of it.

And then something like “The Mansion Above,” which I wrote fifty years ago, somehow fits in there. There is a thread between those songs. So yeah, I think to see a line through of faith is good.

You’ve mentioned before that you’re doing what you call “three-day-weekend touring.” What are your upcoming “weekend” plans?

RG: Our approach to touring is very chill. We do two or three dates in a row, sometimes just one-offs. That’s our usual mode. I think the most we’ve ever done in a row is four dates. It’s all compact and it’s all about being humane and kind to ourselves.

KK: We have a good time. We have a comfortable car, I do all the driving and Rayna does all the navigating and mans the phone. I like to get onstage and play, but I don’t think either one of us wants to go, “Let’s book a month.” I look at other people’s schedules sometimes and go, “I remember doing things like that,” but I wouldn’t want to do it again.

We are gentle on ourselves. Our performances– we’ve cut that down in the sense that we don’t use any monitors onstage. We sit as close as humanly possible together and still be able to move the instruments around. Sound people really like us because sound people hate monitors. You say, “No monitors,” they rejoice. Doing it that way, if a soundcheck takes more than 15 minutes, we’re in trouble. Two instrument mics, two vocal mics, no monitors. “Can you hear us? Great. We’re done.” It makes life simpler.

RG: So yes, we do have gigs. There’s some stuff for the summer that will be posted on our website and I’m working on fall right now.

KK: And we are open to offers.

RG: Yes, we’re always happy to hear from venues!

Photo courtesy of the artist.