Alison Brown heard Earl Scruggs playing on the Foggy Mountain Banjo album when she was 10 years old – and it changed the course of her life. More than 50 years later, Brown is the newest honoree at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s Louise Scruggs Memorial Forum.

Yes, the circle really is unbroken.

Brown has received countless awards throughout her career as a groundbreaking banjo player. This time, however, she will be recognized for her many contributions to the business side of music.

The museum states that “The Louise Scruggs Memorial Forum recognizes a music industry leader who continues the legacy of trailblazer Louise Scruggs, a formidable businesswoman who set new professional standards in artist management.”

Michael McCall, CMHOF’s Associate Director of Editorial, said, “We always try to look at the people who are important in country music, but who the public may not know about.”

The forum began in 2007 with a mission to acknowledge Louise Scruggs’ remarkable contributions in light of the fact that “women don’t always get the recognition they should,” McCall said. “The forum is a way to shine lights where they don’t always shine.” Brown is the 17th honoree.

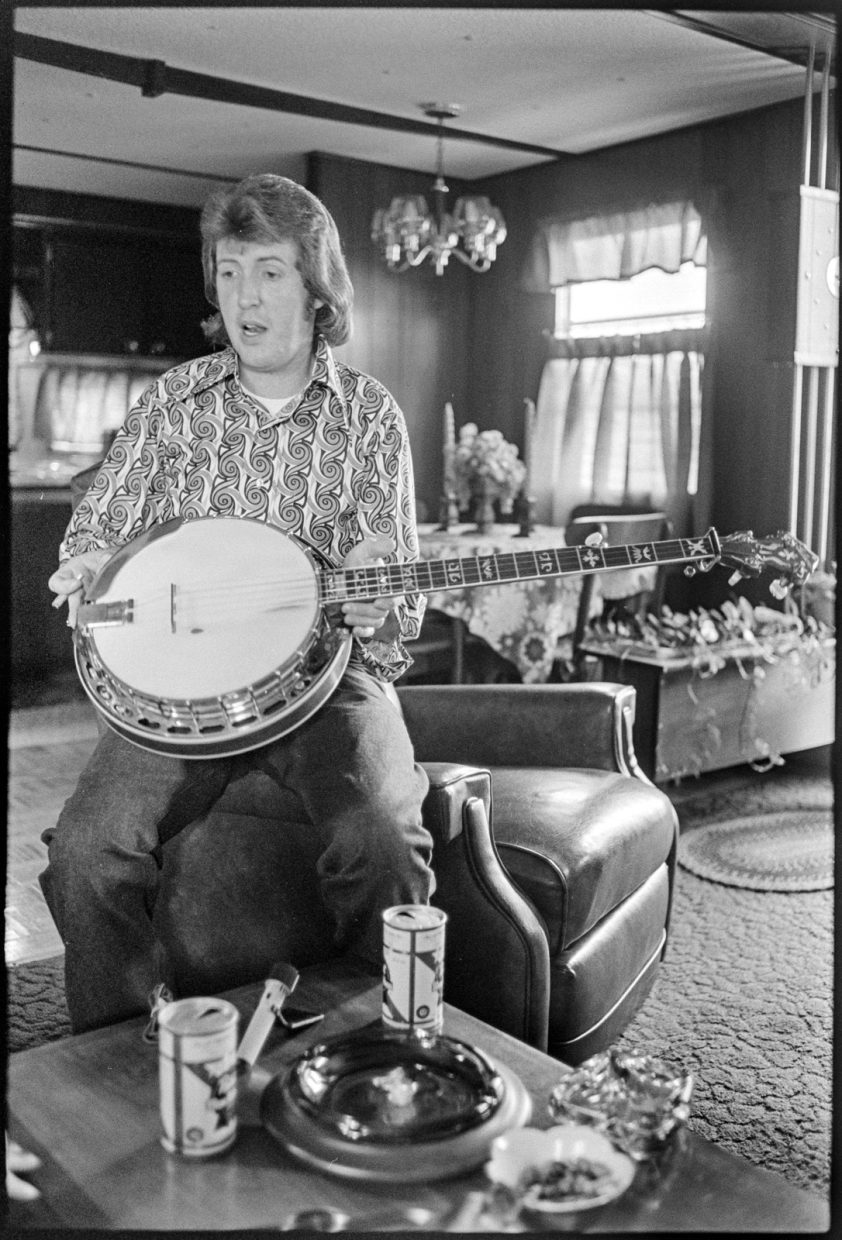

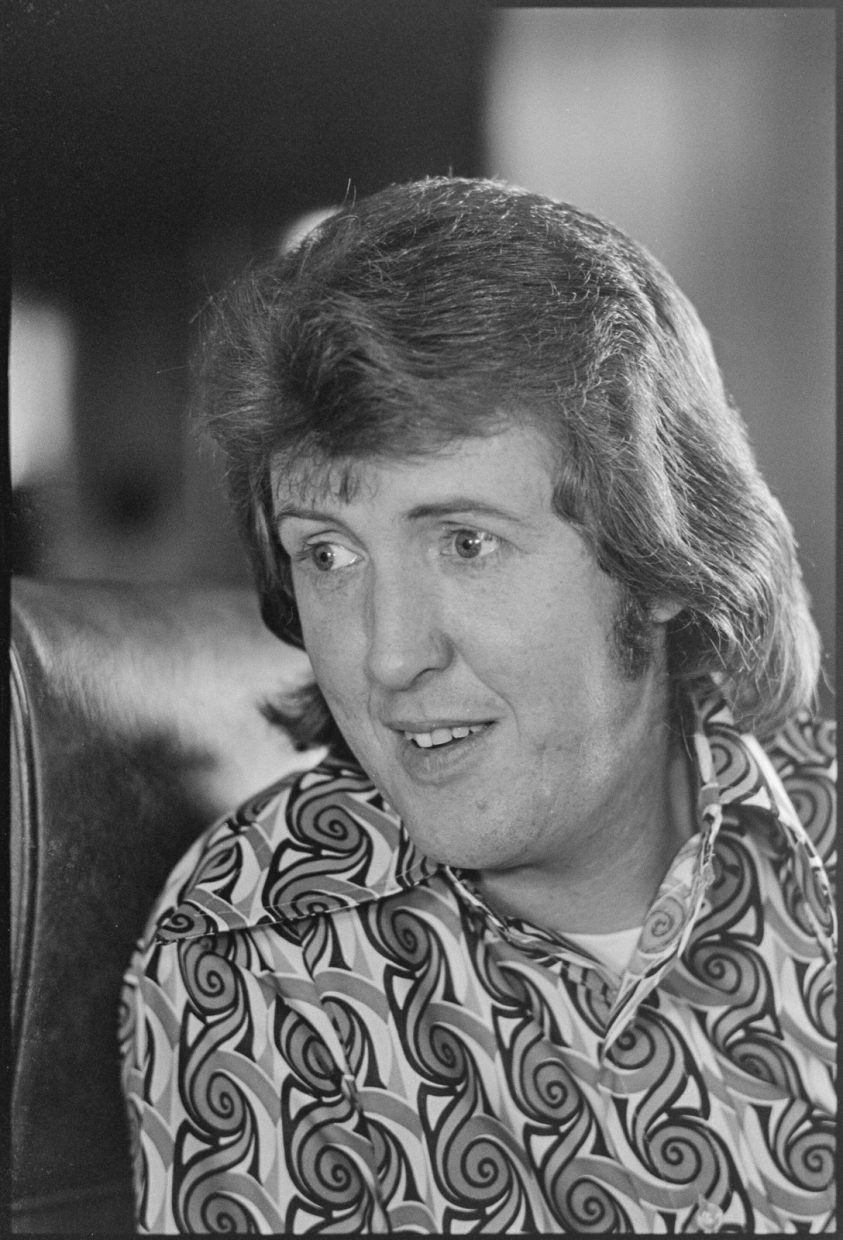

Marty Stuart once told writer Jon Weisberger that Louise Scruggs “was to the business what Lester and Earl were to the music.” While performing with Bill Monroe, the “Father of Bluegrass Music,” Earl Scruggs introduced audiences to the three-finger style that we now think of as bluegrass banjo. That driving syncopation was one, possibly the primary, feature that separated bluegrass from the other forms of what was then called “hillbilly music.”

Decades later, bluegrass banjo players, almost without exception, cite Earl Scruggs as a primary influence.

While Louise’s impact isn’t as widely known, she was an equal force in the music industry. She turned the management of bluegrass artists from a casual afterthought to a profession. And her instincts and cultural awareness started ripples that are still expanding today as bluegrass, folk, and country meet in the land of Americana.

Louise was born in 1927. Shortly before she died in 2006, she told The Tennessean, “My mother worked her fingers to the bone, and my daddy did, too, and I didn’t want to go out in a field chopping corn.”

She developed office skills to fulfill a desperate determination established during the Great Depression to escape farm life. Those abilities set her on a path that in some ways changed the trajectory of bluegrass music. At the time, the bluegrass world was totally male-dominated on both the entertainment and business sides.

“But Louise was so good at what she did,” McCall said, that she was a total success. She overcame any resistance with her “integrity, and by being both hard and fair in business.”

Earl Scruggs and Lester Flatt started an immensely successful band in 1948. But it wasn’t just Lester’s voice and Earl’s banjo that made Flatt & Scruggs household names. It was Louise.

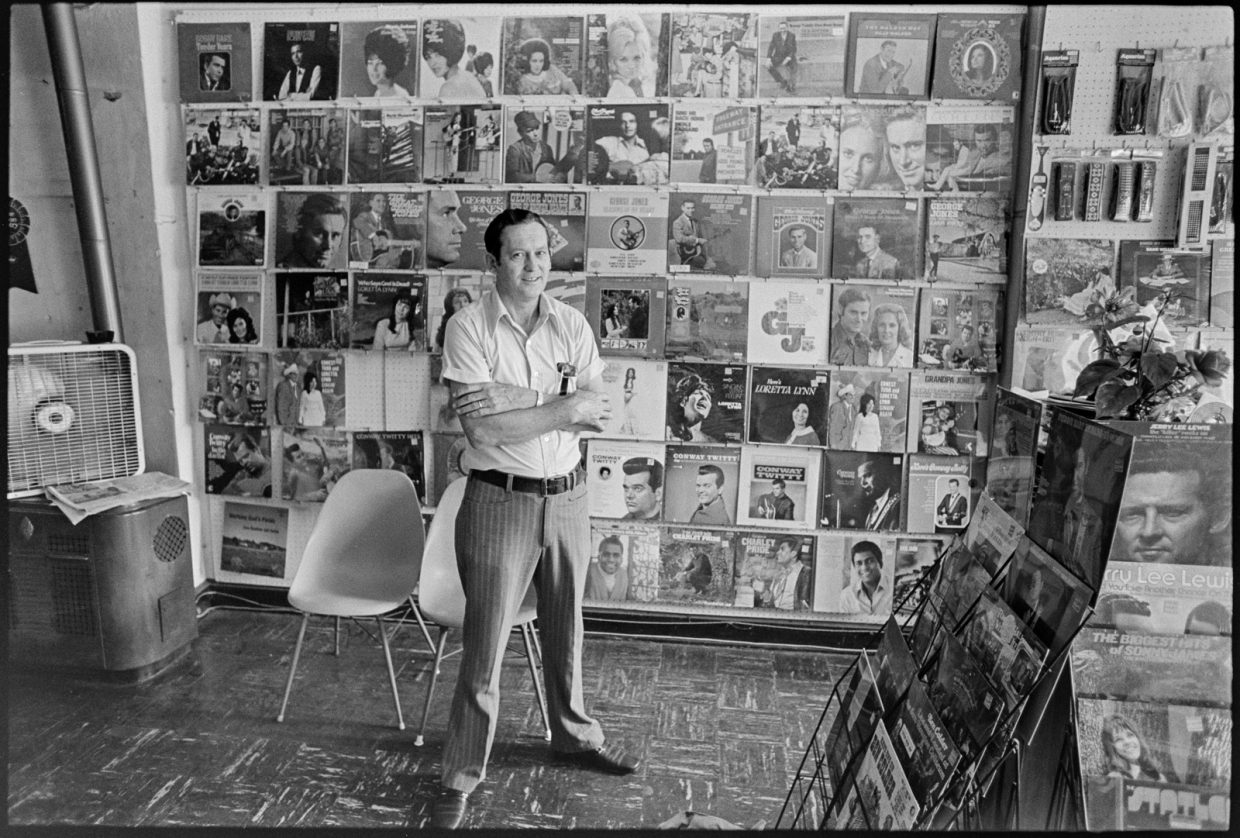

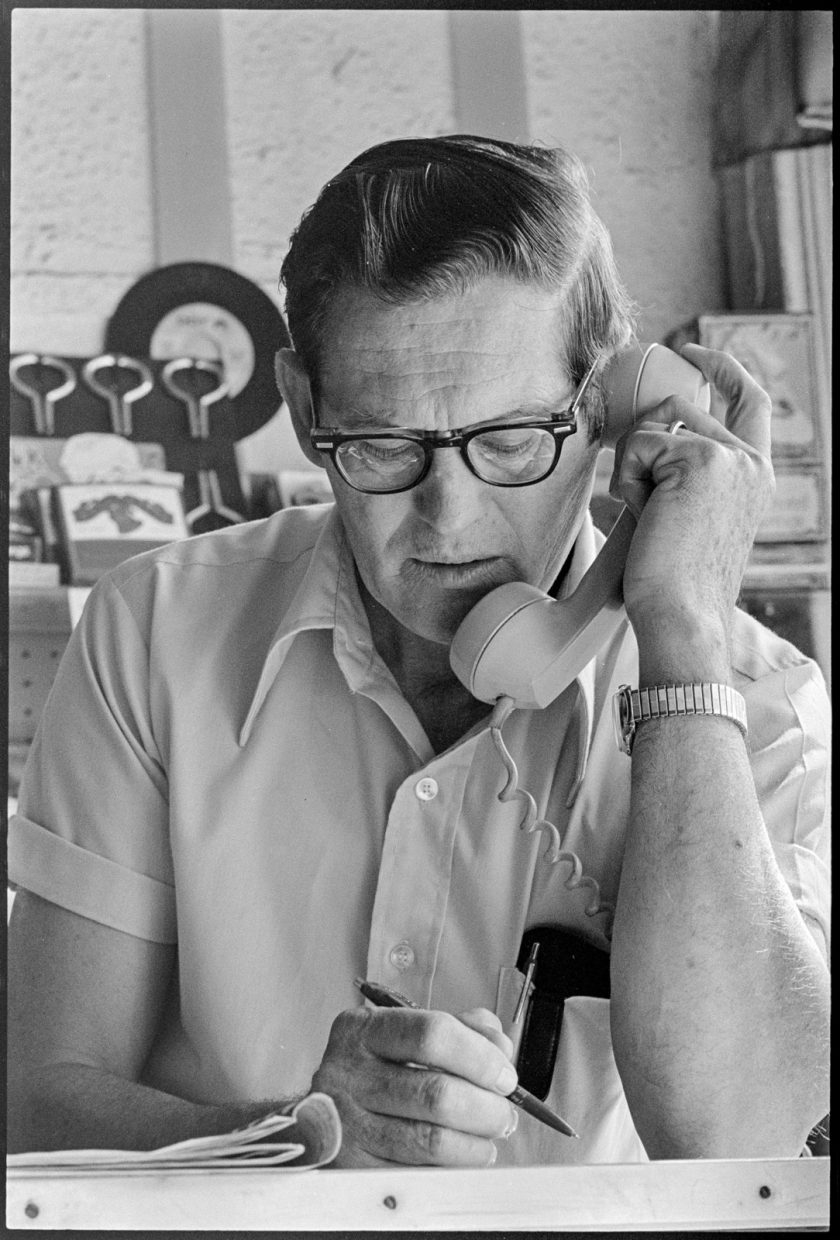

Louise had been working as a bookkeeper when she fell for Earl Scruggs, seeing him on stage as a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. After marrying Earl, Louise initially stayed home to raise their three children. In 1955, she took over management of Flatt & Scruggs, becoming the first female manager and booking agent in the music industry.

In addition to excelling at contract negotiation and other financial aspects of talent management, Louise was a visionary. She pursued the potential of various media previously untapped by bluegrass, as well as navigating shifting cultural trends.

When Louise negotiated with CBS for use of “The Ballad of Jed Clampett” and appearances on The Beverly Hillbillies, the sound of bluegrass banjo was heard in living rooms across the nation – well beyond the coverage of the Grand Ole Opry. The theme song to Petticoat Junction kept the momentum going.

With “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” featured in the popular film Bonnie & Clyde, banjo teachers were inundated with requests to take new students.

Louise established Earl as part of the folk revival when she booked him into the first Newport Folk Festival. New York City audiences opened their ears and hearts to Flatt & Scruggs when the band appeared at Carnegie Hall. Louise also encouraged these revered bluegrass musicians to incorporate songs written by contemporaries like Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash; Earl even made some recordings with saxophonist King Curtis.

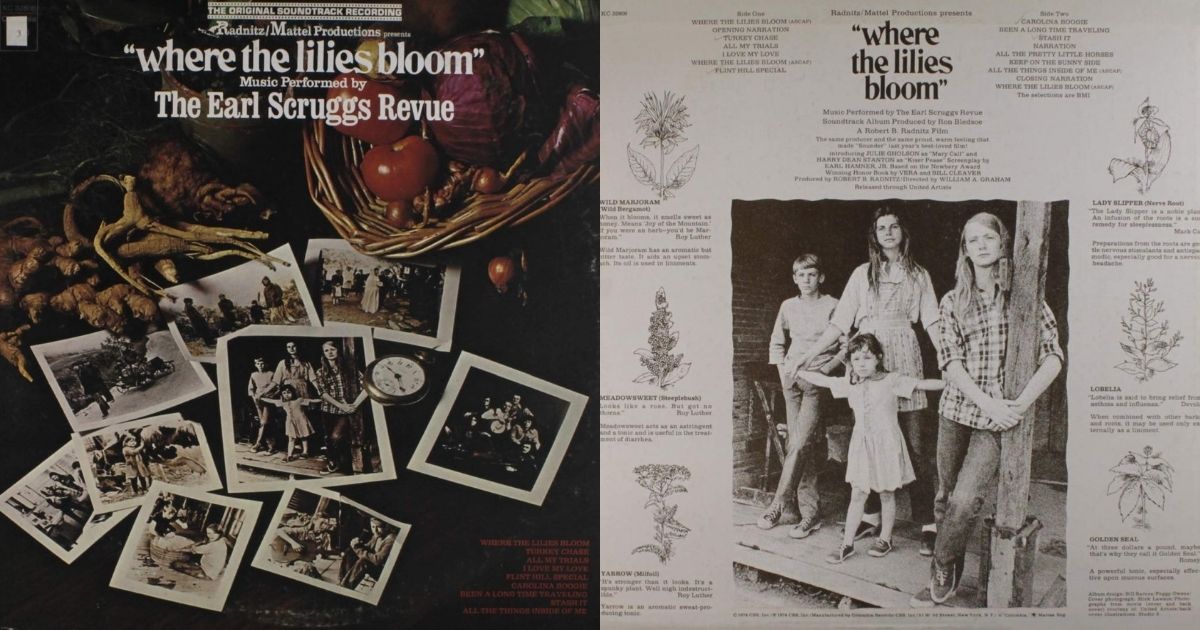

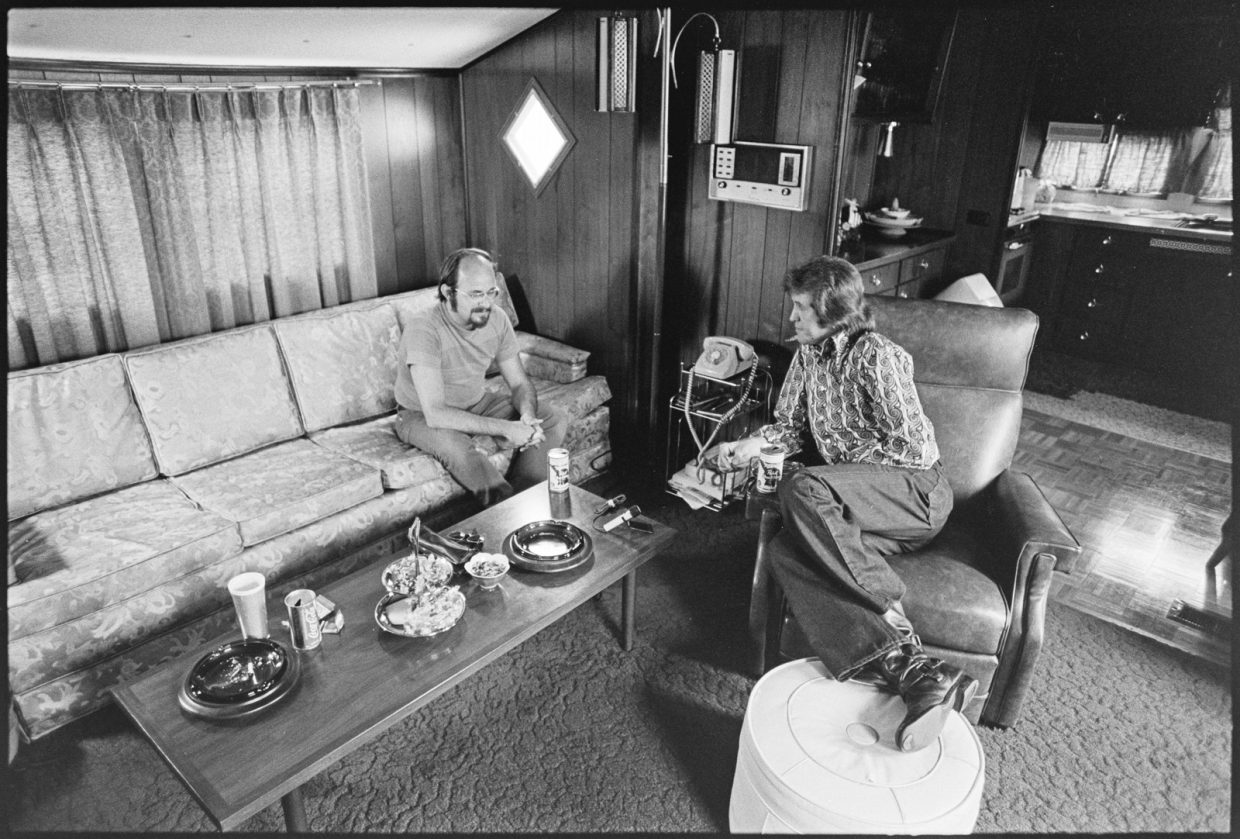

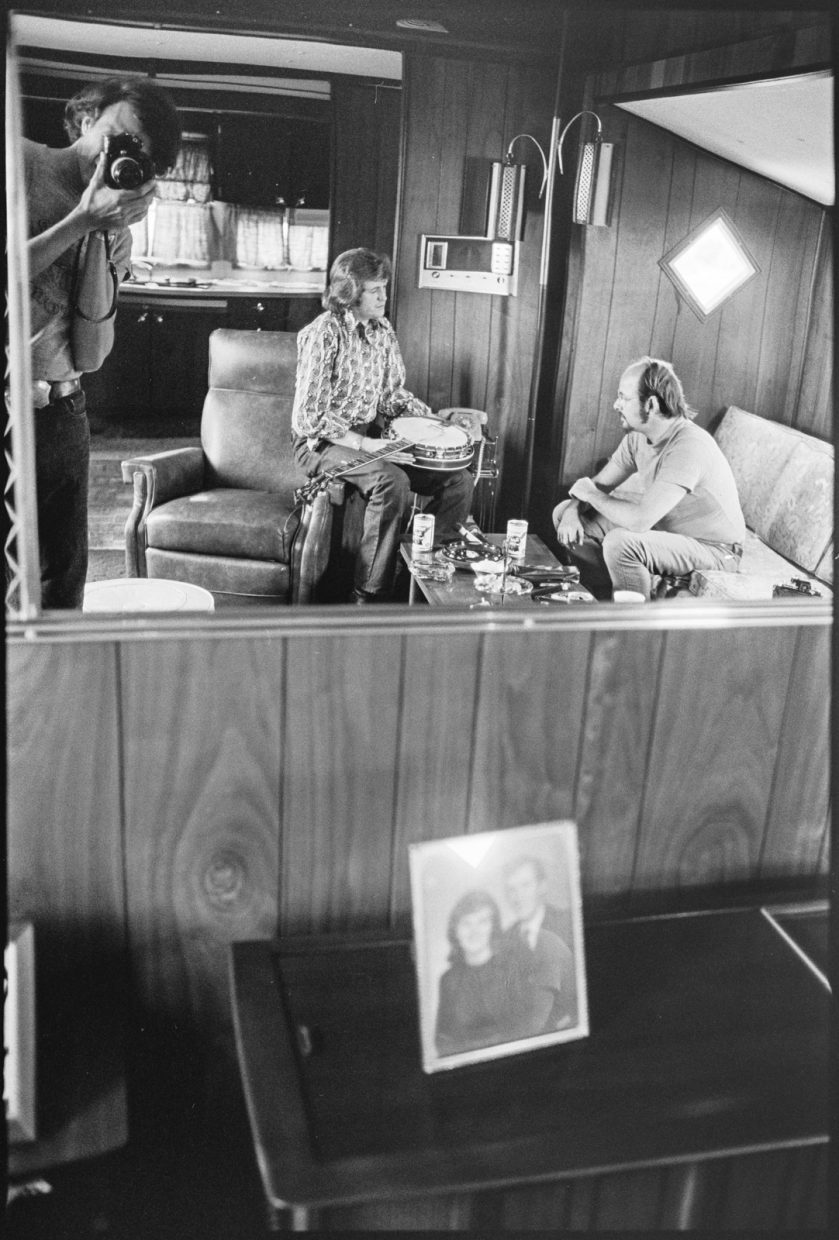

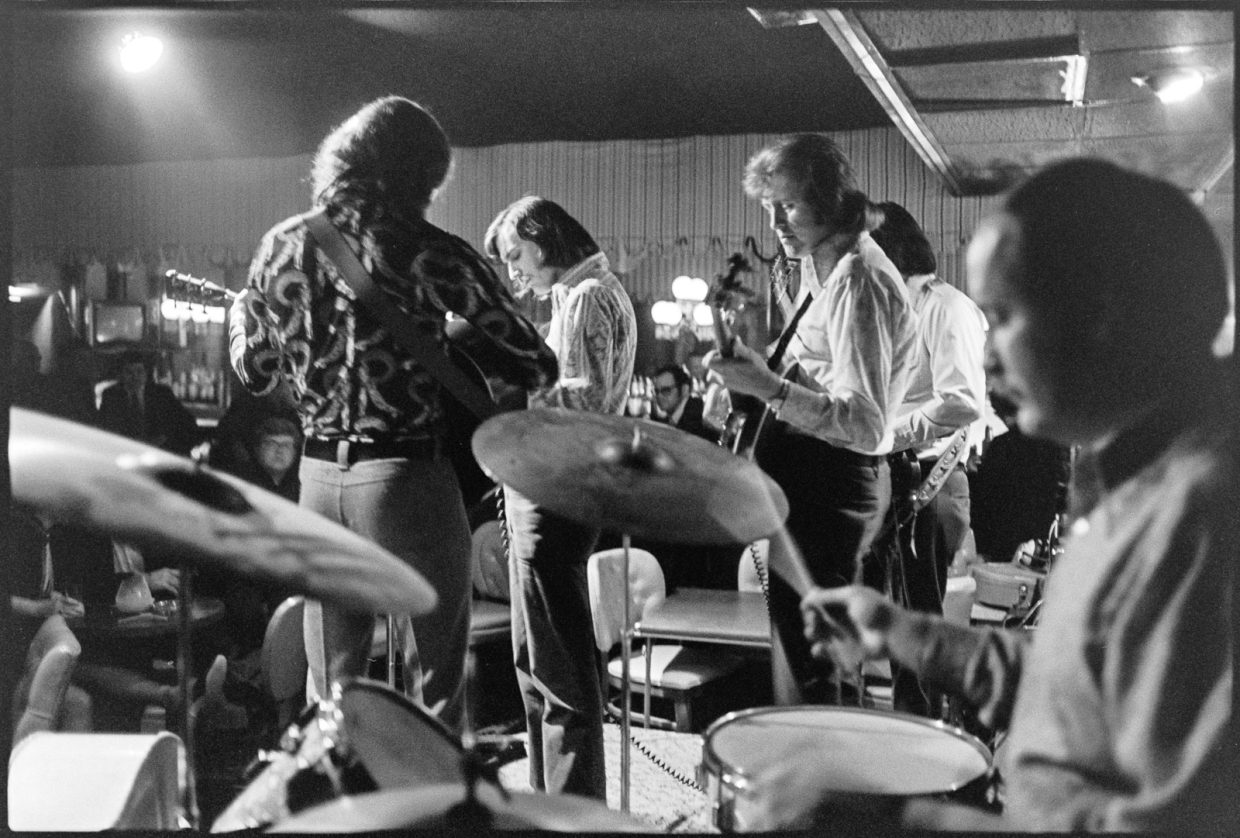

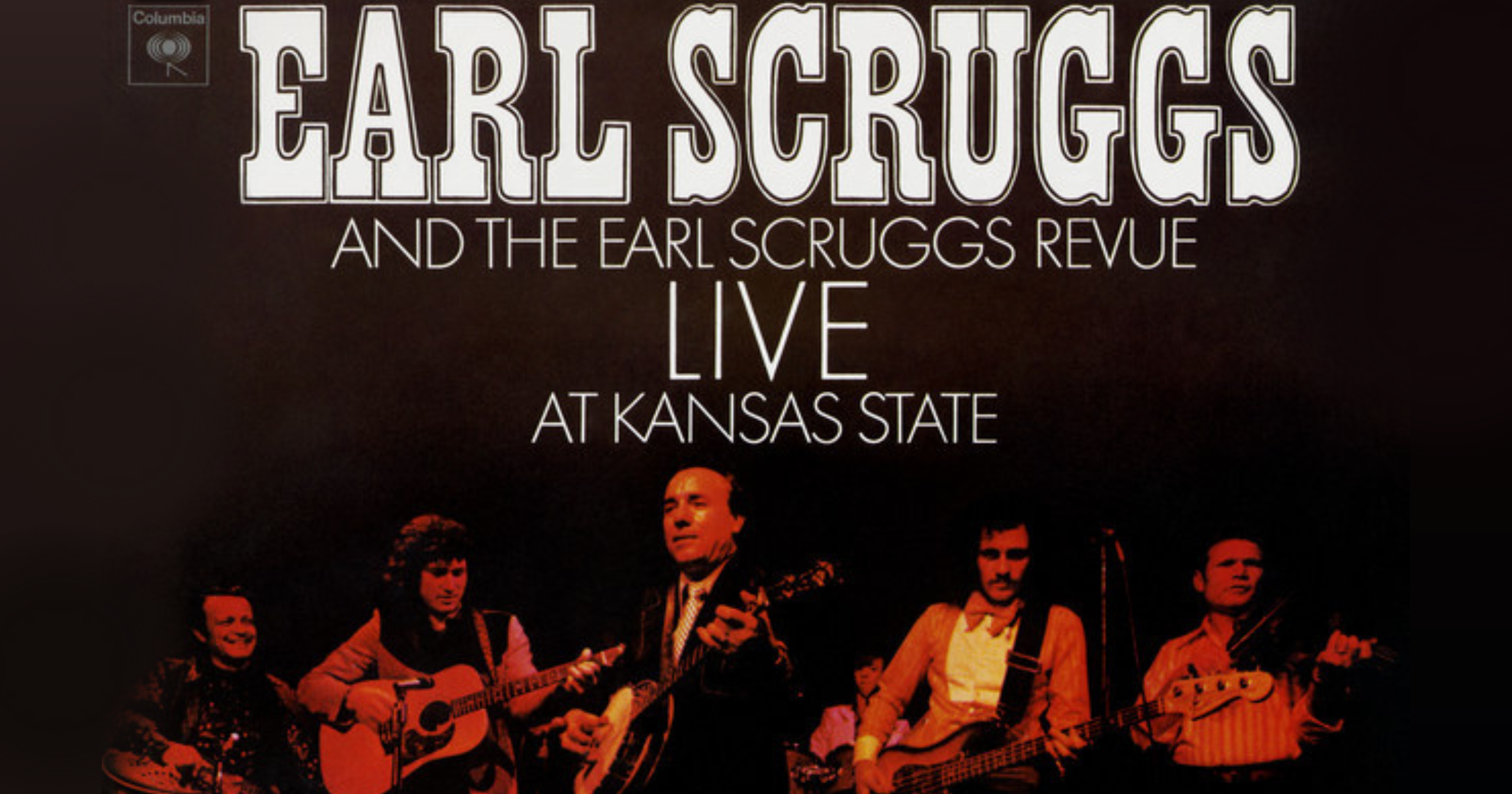

Flatt didn’t appreciate the expanded repertoire and he split from Earl in 1969. Louise quickly helped form the Earl Scruggs Revue with their sons, a “beyond-bluegrass” ensemble enthusiastically received on college campuses and at festivals. They performed with acts like Steppenwolf and The Byrds and they appeared at a major anti-Vietnam War demonstration in Washington, D.C., in 1969.

The Country Music Association’s CEO Sarah Trahern said of Louise, “She was blessed with charm, intelligence, a puritan work ethic, and a wonderful sense of humor.”

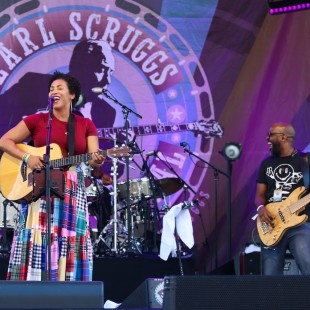

The same can be said about Alison Brown, the 2025 honoree. To say Alison Brown is admired as a banjo player hardly touches the music community’s regard for her talents.

Once she heard Earl play at age 10, Brown never let up on the banjo, winning contests at a young age and working across her entire career to expand the banjo’s role in acoustic music.

She was the first woman to receive an Instrumentalist of the Year award from the International Bluegrass Music Association on any instrument. She has won GRAMMYs and has been nominated for others and she is in the Banjo Hall of Fame.

Kristen Scott Benson, six-time IBMA Banjo Player of the Year – the second woman to receive the honor – recalls hearing Brown’s Simple Pleasures CD. “It was the first time I had ever heard any banjo playing outside the bluegrass realm. I was completely fascinated and my ears were opened to a whole new world of writing and playing.”

These days Brown frequently writes and performs with fellow banjo player Steve Martin and receives rave reviews for numerous other collaborations.

When Brown graduated Harvard with a history degree, she faced the question of what to do next. Realizing that neither the humanities nor banjo playing were money makers, she adopted the attitude of, “A girl’s gotta eat, right?”

She was accepted into UCLA business school and spent three years in investment banking. Then Alison Krauss beckoned her back to professional banjo in the early days of Union Station.

This eventually led her to performing with Michelle Shocked and to meeting her husband-to-be, Garry West. Cut to an Alison and Garry discussion in a Stockholm café about the elements of a good life. They still have the napkin on which they jotted words like performing, recording, having a label, a studio, publishing – and family. That was how the idea for an independent record label was born.

Small World Music began with the goal of distributing music by little-known artists they heard while on tour. Initially, they worked with a tiny Australian company, promoting six products in their catalogue.

“There was a video called ‘Coral Sea Dreaming’ that was visual music – beautiful scenes of coral reefs, set to a new age soundtrack,” Brown described. She and West thought it would be perfect for the Nature Store chain, but the buyer ignored their overtures.

So, Brown said, “We started calling Nature Stores and saying that we’d heard about this amazing video called ‘Coral Sea Dreaming’ – did they have it in stock?” And a few days later, the buyer called them.

“That was one of the first big things that helped our cash flow, leading to the launch of Compass.”

While she had been happy to leave the dry work of entry-level investment banking, she appreciates the knowledge she acquired there and in business school. “Like how to put together a business plan and the financial projections to support it. It also gave me paper credibility,” with investors.

Compass Records has evolved to become one of the most respected independent labels in the industry, specializing in niche markets like Celtic, folk, bluegrass, Americana, jazz and many varieties of roots music.

The business environment Brown entered when she started Compass Records in 1995 was a far cry from the all-male world that Louise Scruggs operated in.

“I’m a firm believer that we all stand on the shoulders of the people who have come before us. And that’s incredibly true for me as a woman in business. I’ve never had to deal with those kinds of challenges [being undervalued or ignored] as a female.”

Brown and West planned their lives so they could start a business, support their love of music, and raise two children – building in the resources they needed for balance and family time. Technology and changing gender roles made all that possible in a way that wasn’t available in the 1950s. But while she didn’t encounter the same challenges as Louise Scruggs, she finds herself facing more profound obstacles.

“The digital transformation has changed the music business, maybe more than any other industry,” she said. “How do you exist in an ecosystem where you’re creating music and having to give it away for free?”

Brown was recently elected president of the Nashville Chapter of the Recording Academy. She has assumed a leadership role in promoting the rights of artists and labels and she is a determined advocate for equality of broadcast royalties – more important than ever when “streaming pays a third of a penny per stream.”

“That’s a rate conceived by the Copyright Board before people knew that a stream wasn’t a small river,” she said. “I feel like this is a critical time for creators, and I fear that, with so many people in Washington in the pocket of big tech, creators’ interests could very easily become marginalized in this race for AI.

“It’s a precarious moment, but at the same time, I feel like some of the best roots music and bluegrass music that’s ever been made is being made now, and I think it will stand the test of time.

“I think that cultivating your community is the key to succeeding – knowing who your fans and supporters are and making sure they know who you are. And now we have the tools to connect directly with our audience, which we didn’t have when we started 30 years ago,” Brown said.

She also reminds fans that, “If you want to support the artists, buy physical product. That’s still where the artists can make some money.”

Marian Leighton Levy, who started Rounder Records in the 1970s along with two partners, knows the challenges of an independent label. And she is well aware of how much more competitive the industry has become in the face of consolidation; artists’ ability to produce their own product; and the devastating effect of streaming on creators’ incomes.

Levy said of Brown, “She’s one of the few people who’s been a top-level musician, someone who knows her way around the studio as an engineer and a producer, has started and been running a record company with Garry and somehow or other had as balanced a life as one can have while doing all of those things. And she’s been doing remarkably well for a very long time – it is just incredible what she’s accomplished.”

At the Hall, McCall lauds Brown not only for her success with Compass, but with all the ways she contributes to the industry – from participating in IBMA to the Recording Academy to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum itself.

Brown feels deeply honored to be recognized at the Louise Scruggs Memorial Forum, “having been called Girl Scruggs for so much of my childhood.”

“Louise was such a wonderful, influential force in roots music, being acknowledged as following in her footsteps is incredibly meaningful.”

She sees the forum as a great contribution to the business of music by acknowledging how far the industry has come.

“One of the things that I think is so exciting about the moment that we’re living in is that women are peppered throughout the ecosystem in a way that wasn’t the case 50 years ago. We have women promoters, artists, DJs, running record labels. Now we have this golden opportunity to create the reality that we want to live in, and we can do that by supporting each other.”

Photo courtesy of the Country Music Hall of Fame & Museum.