When it comes to the rich, vibrant musical landscape that is American music, few bands have the sonic range, technical capabilities and curious prowess as that of Leftover Salmon — bluegrass to blues, country to Cajun, rock to roots, jazz to jam.

And it’s that jam element at the melodic core of Salmon. They jam under the cascading snowflakes atop a Colorado ski slope or with beads of sweat rolling down their faces in the backwoods of Florida. They jam early in the morning or way late into the night. They jam for massive crowds or simply for themselves. What matters most is the music and where it can take you, onstage and on the road.

Though Salmon is in the midst of its 35th anniversary celebration, the actual timeline goes back four decades, where, in 1985, a young guitarist named Vince Herman took off from West Virginia in search of the “mythical bluegrass scene” in Colorado.

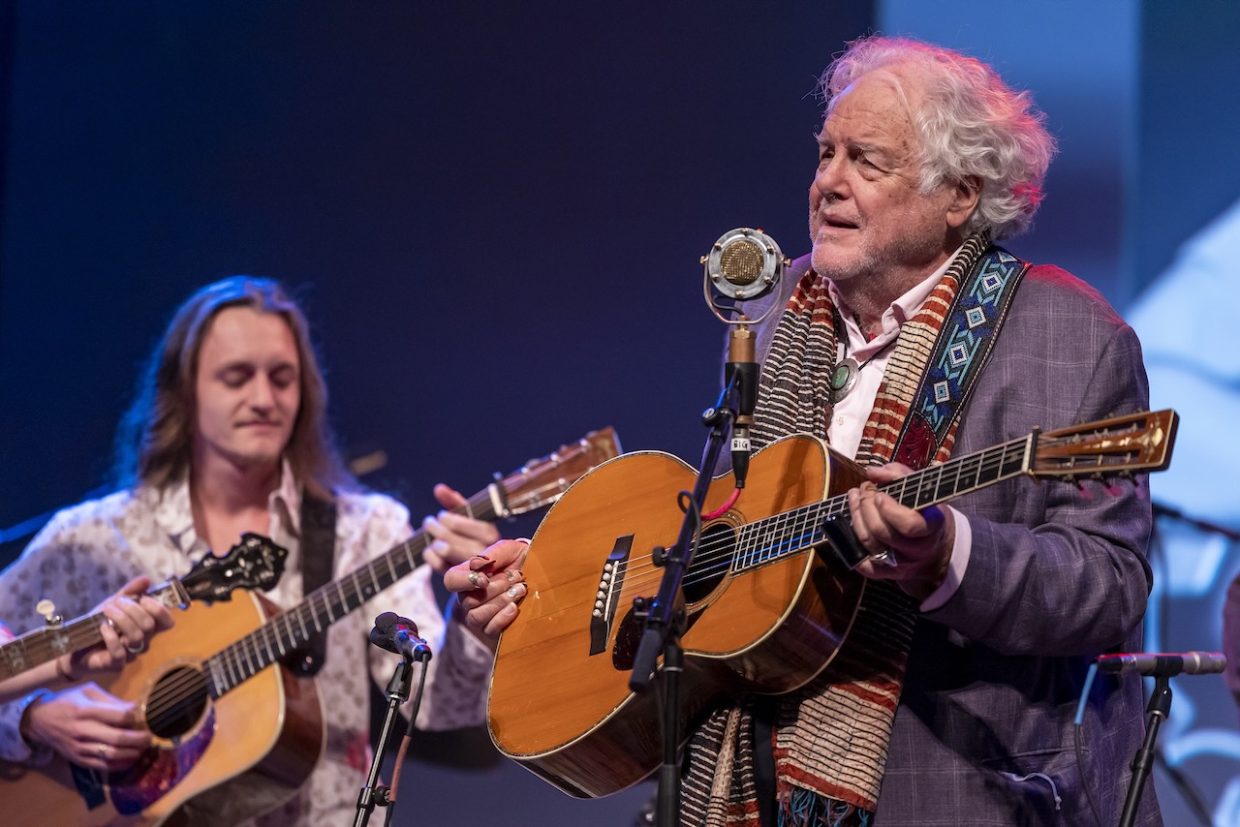

His quest eventually led him to a bar in Boulder one night, the same evening a talented multi-instrumentalist, Drew Emmitt, was performing onstage in the Left Hand String Band. The sign on the door said “Live Bluegrass Music Tonight,” so Herman strolled in.

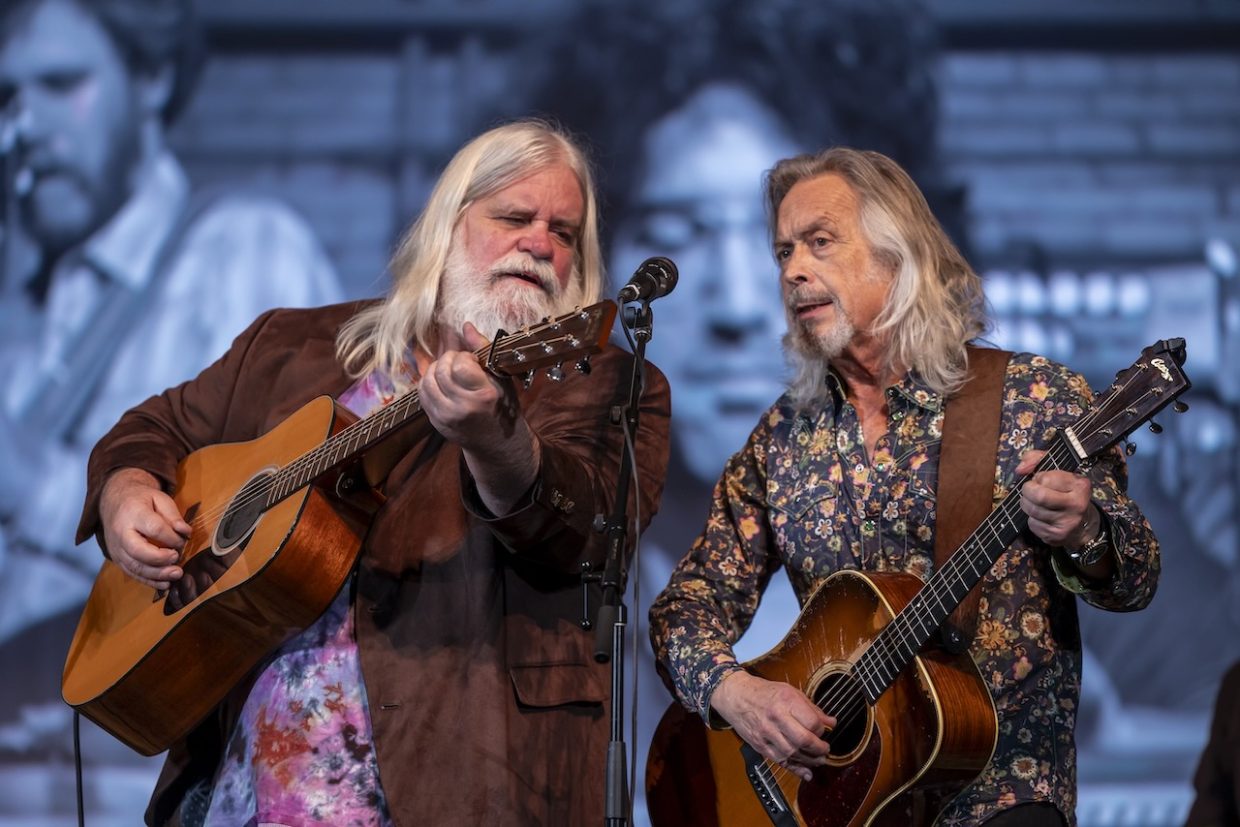

From there, the duo became inseparable, ultimately joining forces in 1989 to play a New Year’s Eve gig in Crested Butte under the name Leftover Salmon (a combination of Emmitt’s band moniker and Herman’s short-lived Colorado group The Salmon Heads).

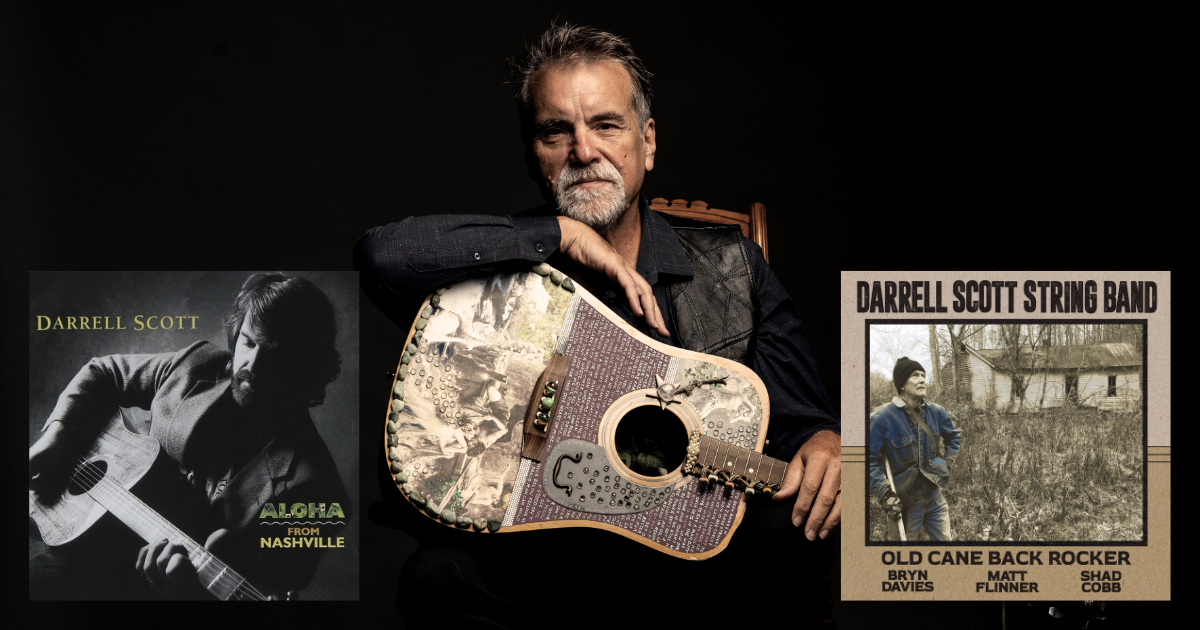

With Salmon’s latest album, Let’s Party About It, the outfit once again rises to the occasion, providing soothing, feel-good tunes that radiate gratitude, graciousness, connectivity and compassion in a modern era of uncertainty, confusion and fear.

Backstage before a show in Asheville, North Carolina, Herman and Emmitt talked at length about the road to the here and now. In simplest terms, Leftover Salmon is currently riding a big wave of popularity and cultural importance — a high-water mark of its legend, lore and legacy.

What spurred you to go to Colorado in 1985?

Vince Herman: It was fall [in Morganton, West Virginia]. It was getting cold in this place I was living, which was in an attic of a house that we were remodeling. It didn’t have any heat. I went to college there [at the West Virginia University] and had six credits to go. I kind of ran out of motivation and it was getting cold. We just figured it was time to do something else.

Why Colorado?

Well, it was the bluegrass scene there. I was playing a lot of old-time and some bluegrass in West Virginia. And I knew there was a progressive bluegrass scene based around the Telluride Bluegrass Festival. The band Hot Rize was in Boulder, which was a major influence on me. So, I figured Boulder would have a good progressive bluegrass scene. And it sure did, proven by pulling up and seeing a “Live Bluegrass Music Tonight” sign [at a bar].

Did you drive across the country by yourself?

No, I came across with a guy named Lou Pritchard. There’s all kinds of Pritchards in the music business. He’s a teacher [now] in southern West Virginia. So, I threw the dice and sold a guitar to make the trip. We lived the first week in a storage shed. We rented it. It was a storage shed, but hell, it had power, you know? [Laughs] The plan was, “Let’s go to Colorado and see what happens.” Lou was thinking about starting a brewery because small breweries were just made legal. I ended up getting a job cooking in a restaurant and just playing tunes on the Boulder Mall. [Back in West Virginia], I was playing for free beer and somebody’s wallet, played a little bit in a Grateful Dead band called Nexus. But nothing professional in any way.

Were there aspirations to start a band and really give it a go?

Yeah, definitely. It was, “Go to Colorado and find like-minded players.” I didn’t know for sure whether I’d have a music career, but other things were totally unsatisfying. I’ve had a lot of jobs, man. I’ve been a cook, bartender, fisherman, roofer, painter, landscaper. I’ve done all the jobs you can imagine. But this is by far the best.

So, your first night in Boulder, the stars align. You walk in on a bluegrass jam and run into Drew, who’s been with you since that moment.

VH: Yeah, it’s been 40 years. I said hello [to Drew] that night and, I guess, it was probably six or nine months later I was in the Left Hand String Band. I did about a year there, and then they got a better guitar player. So, I started The Salmon Heads after I got kicked out of Left Hand. [Laughs]

You told me one time that if you tried out for Salmon now, you wouldn’t get in.

Oh, for sure. Definitely. My philosophy has always been to be the worst player in any band I’m in. So, it has served me well over the years. [Laughs]

So, New Year’s Eve 1989, you form Leftover Salmon.

We went through every combination of those two band names — Left Hand String Band and The Salmon Heads — and stuck with Leftover Salmon for the first night, never knowing it would be any more than one night of a gig [in Crested Butte]. The older the tune, the more the bluegrass stomp kind of thing would go on, people would slam dance. We were like, “Something’s good about this.” And we had a bunch of gigs the next morning. All the bar owners talked to each other. There was no plan [to form a group], but we got all those calls the next morning to book the band.

[Drew Emmitt enters the backstage area and sits down.]

What about for you, Drew? You and Vince have been together for 40 years. What was it about Vince that you felt this was a guy you wanted to play with?

Drew Emmitt: Well, I came from more of a bluegrass-serious kind of world. And I always loved the lightness that Vince always brought to the music, all the fun. Playing music with him was always fun, and singing with him. He’s got a very powerful voice. We both sing kind of loud, so we sing well together. The lightness and the fun factor — that’s what, in so many ways, has driven this band. It’s just always been fun. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been onstage just laughing hysterically because there’s so much madness going on.

I’ve been following you guys for almost 20 years and, no matter what kind of day your day is, you’ll always have fun at a Salmon show. And it seems, lately, that there’s a reinvigoration in the band, a few more logs being thrown on the fire.

VH: Absolutely. Jay Starling on keys, dobro and lap steel adds a great element to it, you know? And [drummer] Alwyn [Robinson] and [bassist] Greg [Garrison] together in the rhythm section. It just brings such energy to it. And Drew, [banjoist] Andy [Thorn] and I just get to ride on that stuff.

What is it about Drew that works for you?

VH: He’s relentless, man. (Turns to Emmitt). You hit that mandolin and just get that tremolo going — nobody like it. It sure gets a crowd riled up.

You have a new album out. What does it mean that people still believe in what the band is and what the band does?

VH: Hot Rize was a real major influence. I saw Tim [O’Brien] and was like, “Okay, so we’ll be in this little musical niche.” It’s never going to be the Rolling Stones or Pink Floyd level kind of stuff. But, it could be this niche that I could age in and stay in, and be able to do it for a long time. That’s kind of what the folk/bluegrass world looked like to me. I just feel very lucky to have kind of imagined that so many years ago, and to have actually lived it. It’s pretty unusual and I’m incredibly grateful.

What’s been the biggest takeaway from this journey thus far?

DE: The fact that people are still coming to see us. And it’s still working, and actually working better than it ever had. The fact that we can keep playing this and that it’s still relevant. And there’s this scene that has built up around this music. There’s a lot of different bands out there that are building the momentum, [with] probably the main driver of that would be our buddy, Billy Strings.

And you guys blazed a lot of that path Billy’s walking on.

DE: And we followed in a blazed path. We came up behind the people that blazed it for us. And then we contributed our part of it, which was maybe adding a little more rowdiness, a little more rock and roll. But, keeping with that progressive thing that we learned from Hot Rize, New Grass Revival, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Old & In the Way — bands that were pushing the limits of bluegrass. I love traditional bluegrass, but it’s so fun to take traditional bluegrass and do crazy stuff with it.

Traditional bluegrass gives you the tools to do whatever you want.

DE: Exactly. Because it’s an art form, and you’ve got to learn it if you want to play bluegrass, which I’m still working very hard at, trying to learn to how to do it. What this band has brought to the scene is a levity, a fun factor. Over the years, so many of these amazing musicians have sat in with us, and they always have such a good time because it’s just wide open. Like, for instance, when Sam Bush sits in with us, he has such a good time ‘cause we just let him go.

Is that by evolution or by design, that ethos?

VH: I guess it has a lot to do with the Grateful Dead. You know, really saying, “It’s okay to have fun with music.” Go out looking for stuff in the middle of a jam. It gave us permission to do that, and [the Dead] brought so many people to bluegrass.

DE: And I hope we can keep doing it for a while. I hope that I can keep looking across the stage and seeing Vince for a long time. I’m glad to still be onstage with this guy. [Turns to Herman]

VH: I just keep being reminded of the importance of community, and helping us all get by with this [music]. Thank God we have music in the midst of all this chaos [of modern society], something that brings people together under a positive banner, and reinforces the humanity in all of us — there ain’t nothing better than music to do that.

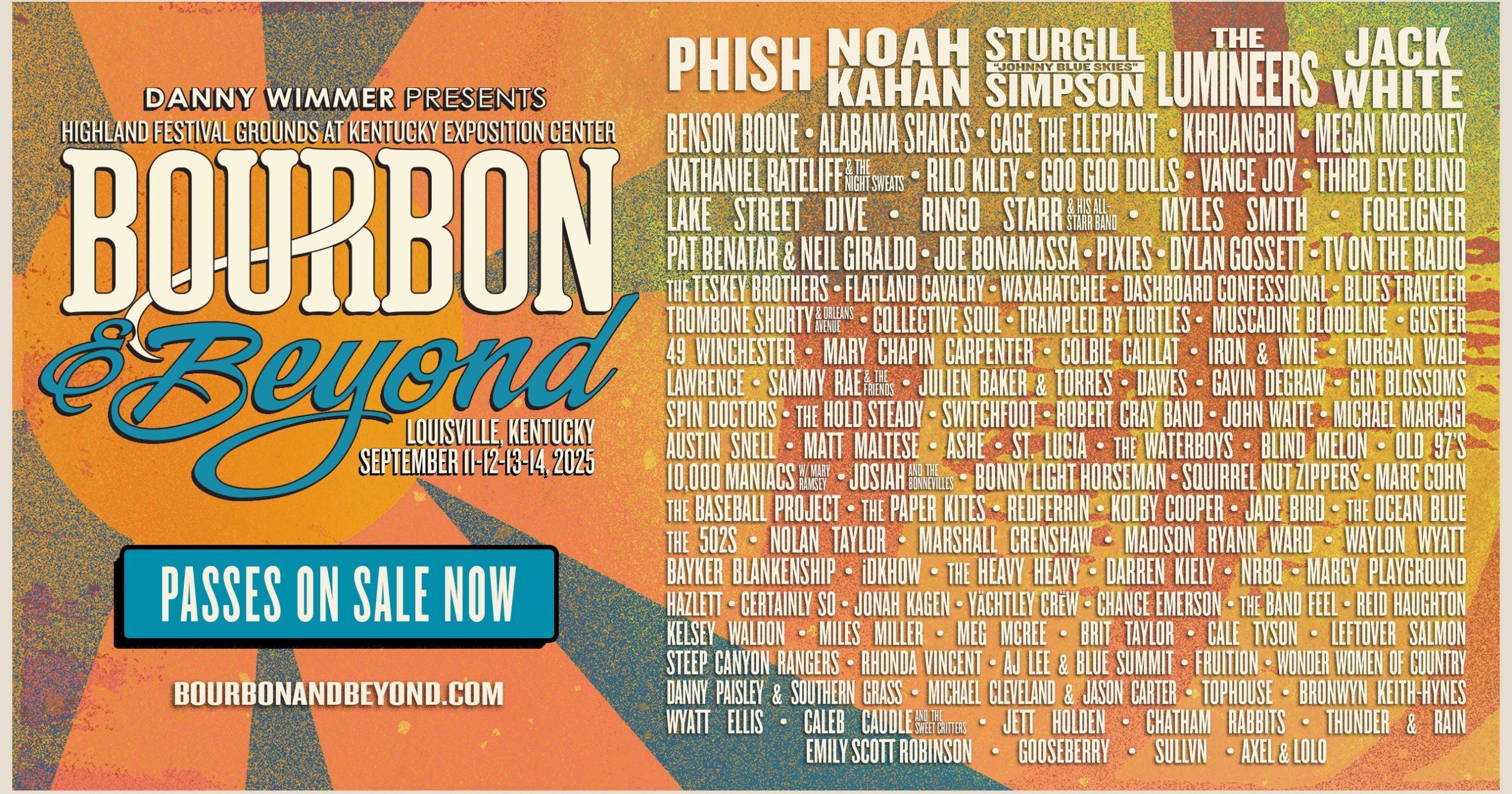

Editor’s Note: Don’t miss Leftover Salmon and so many other great artists on the BGS stage at Bourbon & Beyond 2025. More info at bourbonandbeyond.com.

Lead Image: Tobin Voggesser