On the morning of March 24, 2020 I learned Eric Weissberg had passed away when a friend posted a long and detailed obit. I found several other substantial ones online — Rolling Stone, Variety, New York Times. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that Weissberg’s family had a press release ready; he’d been in decline, suffering from dementia. A few days later Jim Rooney posted a very moving memoir focused on his long-time friend Weissberg in mid- and late years; it shed more light on this influential musician.

Recently Bob Carlin finished a bio on Weissberg. When we spoke at IBMA’s business conference last fall he told me publishers weren’t interested in a book about a studio musician. Too bad, it’s a good story. In 1972 Weissberg won a Grammy for the banjo hit that propelled the growth of bluegrass festivals, “Dueling Banjos,” the theme from the movie Deliverance.

I first heard Weissberg’s banjo playing in the fall of 1957. I was an 18-year old Oberlin College freshman who’d gotten into folk music as a high school student in Berkeley, California. This was my first time “back east.” I now had classmates from New York City. One of them, Mike Lipsky, had a new Folkways album, American Banjo Scruggs Style. The final band on the second side was by a friend of his from New York, Eric.

Weissberg was 17 when he recorded for Folkways, backed by Mike Seeger and Ralph Rinzler. He picked a medley of “Jesse James” and Woody Guthrie’s “Hard Ain’t It Hard,” using Scruggs pegs on the latter. When Lipsky played it to me and my roommate Mayne Smith (fellow Californian and a fledgling banjo picker) he had to explain what Scruggs pegs were.

Lipsky knew about this music because he was one of a group of New York teenage folk music fans, mainly from elite high schools — Bronx Science, Brooklyn Tech, Music and Art — who socialized together. They’d networked not only in school, but also at leftist summer camps where folk music, spearheaded by Pete Seeger, was an essential part of the experience. They called themselves “The Squadron” and they gathered regularly in Greenwich Village on Sunday afternoons to hear two members of their crowd, Eric Weissberg and Marshall Brickman, picking at the Washington Square folk music jams. Weissberg, a student of Pete Seeger, had been playing the banjo since the age of ten.Lipsky told us Weissberg and Marshall’s fancy picking confounded Roger Sprung, an older banjoist generally thought to be the best Scruggs picker in New York. And he described their banjos — not long-neck, open-back Vegas like Pete Seeger played, but Gibsons! With resonators, too. And on the fingerboard, down toward the body of the banjo, a little block of mother-of-pearl with “Mastertone” written on it.

This weirdness was all new to me. I’d never heard of “Scruggs picking,” and it was only when I borrowed the LP and read its notes, written by Ralph Rinzler, that I learned this music was called “bluegrass.”

The following March, at spring vacation, my roommate and I went to New York. I stayed with Mike Lipsky, on this, my first visit to The City. Mayne stayed with another classmate. Among our many adventures — we were rambunctious teen tourists — we went one night to a party for The Squadron in a posh upper East Side residence.

This was a homecoming party. Attending were young women and men most of whom were like us, on spring vacation from their first year as college and university students at a variety of institutions. Lipsky and Karen, another Oberlin classmate who was part of the group, introduced us to their friends. We’d brought our instruments, leaving them in the anteroom and going up a small flight of stairs to the main floor of this elaborate place. Eric Weissberg and Marshall Brickman, both of whom were freshmen at the University of Wisconsin, did the same.

Midway through the evening we were encouraged to get our instruments out and sing. Mayne had his banjo — an old Stewart with a resonator — and I, my guitar — a 1943 Martin 000-21. We went back downstairs. This was the nearest thing to a front porch or back room we could find. We did several pieces, and then Weissberg and Brickman came down and got out their banjos. Mayne had taken one or two lessons with Billy Faier, the virtuoso banjoist who’d arrived in the Bay Area from New York the previous August. Faier had introduced him to three-finger picking. Mayne chatted about Scruggs with Eric and Marshall.

Then they played a banjo duet, a Scruggs tune, “Earl’s Breakdown,” in harmony, with each picking with the right hand on his own banjo while reaching around to fret the strings on the neck of the other’s banjo. This was the first time we’d ever seen anyone play the banjo Scruggs style, much less a fancy stage stunt like that! It was a very impressive tour-de-force. You can get a good sense of what the harmony sounded like from the version on their 1963 Elektra album, New Dimensions in Banjo and Bluegrass (reissued in 1972 as Dueling Banjos from Deliverance) although they weren’t playing the fancy solo breaks in 1958.

Afterwards Weissberg told us that the best way to learn this music was to study Scruggs’ playing on one of his instrumental records like “Earl’s Breakdown” or “Flint Hill Special.” Mastering all those licks note-for-note would take you a long way towards being able to play like Earl.Weissberg noticed that I was playing the guitar with just two picks on my fingers — thumb and index. He recommended that I add a pick on my middle finger, like he and Marshall used for the banjo. I followed that advice immediately, and the following year, when I began working seriously on banjo, I also took his advice about studying Scruggs closely.

Putting our instruments away, we went upstairs and joined the party. I conversed for a while with Eric. I told him I’d heard Billy Faier in Berkeley last summer, had been very impressed with his music, and was looking forward to his forthcoming Riverside album, The Art of the Five-String Banjo. Eric agreed, Faier is a great banjo player, and said he had collaborated with Billy and another banjo player, Dick Weissman, on an album due out this coming summer called Banjos, Banjos and More Banjos!

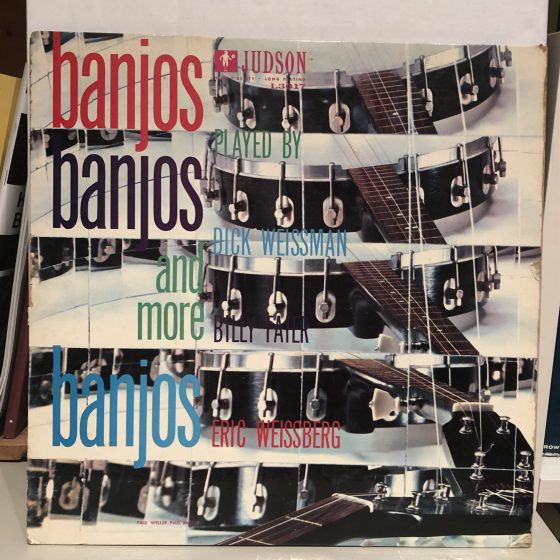

That summer of 1958, Banjos, Banjos and More Banjos! arrived at Art Music on Telegraph in Berkeley where I hung out listening to new folk records. The album was on Judson, a bargain line label owned by Riverside’s Bill Grauer.

Grauer’s Riverside productions catered to the hip college kids of the fifties — a generation that grew up on hi-fi LPs. Riverside reissued historic prewar jazz and blues; released contemporary jazz and folk; and recorded sports car events. This major independent label ended abruptly in 1964 when Grauer, just 42, died. Their catalog is now with Concord Records, which has reissued some jazz recordings on CDs.

Riverside albums were well-produced, with glossy full-color cover art. Back covers — liners — had a standard format: bold head at the top with album title and artist names. Below it, three dense columns giving the playlist along with information about the music and musicians. Lots to read while listening!

Faier’s The Art of the Five-String Banjo liner held a full column endorsement by Pete Seeger, slightly longer notes by producer Goldstein, and Faier’s bio. In contrast the liner of Banjos, Banjos and More Banjos had its playlist followed by three columns of folklorist John Greenway’s flowery history of the instrument, and brief bios for the three banjoists. I bought the album (later reissued on Grauer’s Washington label with new cover and title: Five-String Jamboree: A Treasury of Banjo Music) because Eric Weissberg was playing Scruggs-style banjo on it.

At the bottom of the center column on the liners for both albums was the standard data of the time:

A HIGH FIDELITY Recording (Audio Compensation; RIAA Curve). Produced by Kenneth S. Goldstein. Cover by Paul Weller (photography) and Paul Bacon (design). Engineer: Mel Kaiser (Cue Recordings). New York: May, 1957.

Now I look back at the album, listen to it for the first time in years. When I last heard of Faier, about ten years ago, he was busking in Albuquerque. He died in Alpine, Texas in 2016. We’d seen each other and talked at the Tennessee Banjo Institute in November 1990, recalling the summer of 1958 when I guested on his KPFA show and worked as his backup guitarist at an SF coffee house. Dick Weissman, now 85, had distinguished careers: first as a performer, then as teacher and author. He published his memoir, The Music Never Stops: A Journey Into the Music of the Unknown, The Forgotten, The Rich & Famous, the same year Faier died.

These guys must have been in the Cue Recordings studio more than once in May, 1957. Their recordings were made with a single-track tape recorder; no overdubs. Faier made his solo album at Cue with Frank Hamilton playing guitar, and there’s one track on Banjos with that pairing — probably an outtake from The Art. Most of the other guitar on this album is by Dick Rosmini, then considered the hot, young, go-to guitar accompanist.

Weissberg is heard playing Scruggs-style banjo on five tracks, and singing tenor harmony in duets on three of those. One was an old spiritual, “You Can Dig My Grave,” with Faier. With Weissman, Eric harmonized on the old folksong “Chilly Winds.” My favorite was another spiritual, “Glory Glory.” This vocal duet with Rosmini featured great backup guitar and seven banjo breaks by Eric, each a new variation. I played that track a lot for my friends that summer!

He also did a reprise of his 1956 Folkways track, focusing on “Hard Ain’t It Hard” complete with Scruggs pegs, and a cool version of “900 Miles” in G minor tuning. Weissberg’s music spoke to me as a young folk fan just getting into bluegrass. He’d mastered the instrument in this new style, and learned the vocal style that went with it. Here he was applying it to music that I knew — Woody Guthrie songs, a tune the Weavers had sung on their famous Carnegie Hall concert album, and familiar Black spirituals. The door to bluegrass was newly opened. Eric Weissberg stood just inside, beckoning in. Come on, it’s not that hard, it’ll be fun.

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, and Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee.

Photo of Neil V. Rosenberg: Terri Thomson Rosenberg

Photo of Banjos, Banjos, and More Banjos: Neil V. Rosenberg