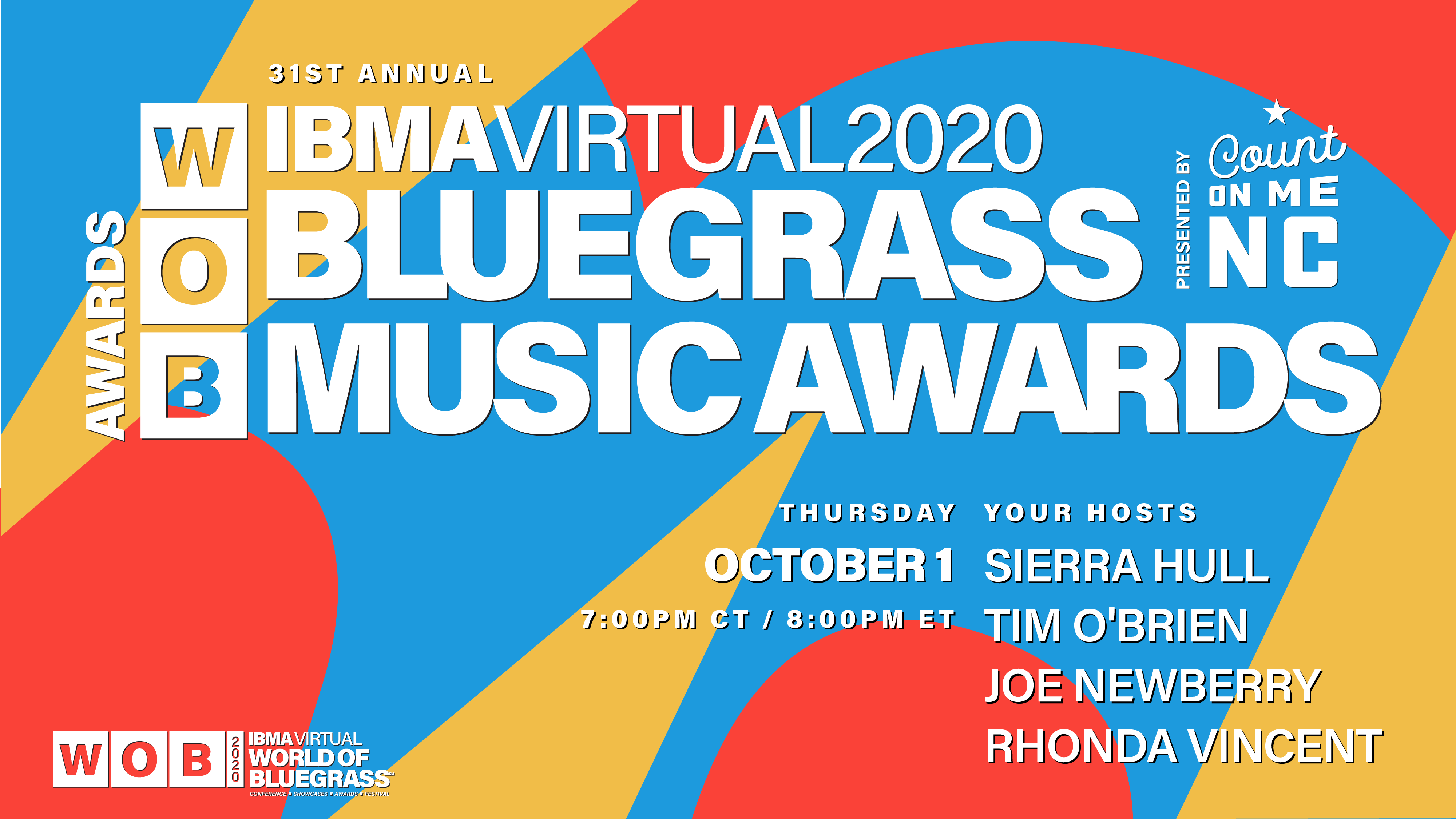

The winners of the 31st annual IBMA Bluegrass Music Awards were announced Thursday night via video awards show, hosted by Sierra Hull, Tim O’Brien, Joe Newberry, and Rhonda Vincent.

The “biggest night in bluegrass” was well-adapted to its virtual setting and boasted three Hall of Fame inductions, guitar and banjo tributes to Doc Watson and J.D. Crowe, a continent-spanning collaboration by Rob Ickes & Trey Hensley and Taj Mahal, and celebrations of the 20th anniversary of O Brother, Where Art Thou? and the 75th anniversary of the birth of bluegrass. Marking the occasion, Del, Ronnie, and Rob McCoury opened the evening from an empty Ryman Auditorium, regarded as the birthplace of bluegrass and a former home for the show.

Special performances were shot live at home, in studios, and at various small venues — as well as the Station Inn and the Ryman. Billy Strings paid tribute to Hall of Famer and Male Vocalist of the Year nominee, Larry Sparks, with a cover of “John Deere Tractor” — with double pickguards, to boot. In the Doc Watson tribute, each of the five Guitar Player of the Year nominees (Trey Hensley, Billy Strings, Bryan Sutton, Molly Tuttle, and Jake Workman) took their turn virtually swapping solos on “Black Mountain Rag,” with T Michael Coleman, Watson’s longtime friend and bandmate, holding them all together through the webcams and headphones. Many other unique collaborations, tributes, and performances were peppered throughout the award announcements. The most stunning performances, though — like Vocal Group of the Year and Entertainer of the Year winner Sister Sadie’s “900 Miles” — were from the mother-church setting of the Ryman, where in a pandemic twist, the bands each performed not facing an audience, but with the auditorium’s empty pews as a background.

As IBMA Executive Director Paul Schiminger put it in his speech from the Ryman stage, in a virtual conference year and a pandemic, returning to the birthplace of the genre was “an unexpected gift through it all.” 75 years of bluegrass were poignantly brought together beneath the rafters of the hallowed, though empty, Ryman Auditorium.

Here are the winners of the 2020 IBMA Bluegrass Music Awards, in the order they were announced:

New Artist of the Year

Mile Twelve

Instrumental Group of the Year

Michael Cleveland & Flamekeeper

Gospel Recording of the Year

“Gonna Rise and Shine”

Artist: Alan Bibey & Grasstowne

Label: Mountain Fever Records

Producer: Mark Hodges

Banjo Player of the Year

Scott Vestal

Resophonic Guitar Player of the Year

Justin Moses

Fiddle Player of the Year

Deanie Richardson

Bass Player of the Year

Missy Raines

Mandolin Player of the Year

Alan Bibey

Guitar Player of the Year

Jake Workman

Collaborative Recording of the Year

“The Barber’s Fiddle”

Artists: Becky Buller with Shawn Camp, Jason Carter, Laurie Lewis, Kati Penn, Sam Bush, Michael Cleveland, Johnny Warren, Stuart Duncan, Deanie Richardson, Bronwyn Keith-Hynes, Jason Barie, Fred Carpenter, Tyler Andal, Nate Lee, Dan Boner, Brian Christianson, and Laura Orshaw

Label: Dark Shadow Recording

Producer: Stephen Mougin

Instrumental Recording of the Year

“Tall Fiddler”

Artist: Michael Cleveland with Tommy Emmanuel

Label: Compass Records

Producers: Jeff White, Michael Cleveland, and Sean Sullivan

Vocal Group of the Year

Sister Sadie

Song of the Year

“Chicago Barn Dance”

Artist: Special Consensus with Michael Cleveland & Becky Buller

Writers: Becky Buller, Missy Raines, Alison Brown

Label: Compass Records

Producer: Alison Brown

Album of the Year

Live in Prague, Czech Republic

Artist: Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver

Label: Billy Blue Records

Producers: Doyle Lawson and Rosta Capek

Female Vocalist of the Year

Brooke Aldridge

Male Vocalist of the Year

Danny Paisley

Entertainer of the Year

Sister Sadie

Also honored during the broadcast were three inductees into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame: owner of the Station Inn, J.T. Gray, The Johnson Mountain Boys, and New Grass Revival.

The Industry Awards were held on Wednesday, September 30. Hosted this year wittily and absurdly in video format by Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn, the Industry Awards recognize outstanding professional work within the many arms and branches of the bluegrass industry at large.

The Industry Awards recipients:

Broadcaster of the Year

Michael Kear

Event of the Year

Augusta Heritage Center Bluegrass Week, Elkins, WV

Graphic Designer of the Year

Michael Armistead

Liner Notes of the Year

Katy Daley, Live at the Cellar Door – The Seldom Scene

Writer of the Year

Derek Halsey

Sound Engineer of the Year

Stephen Mougin

Songwriter of the Year

Milan Miller

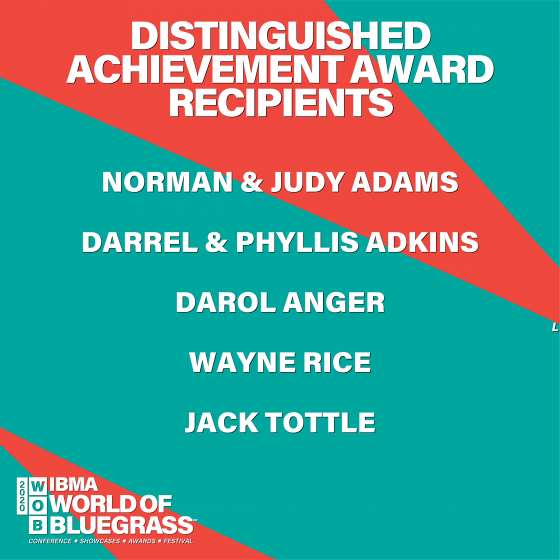

The recipients of the Distinguished Achievement Awards, honoring lifelong contributions by forerunners and ambassadors for bluegrass music, were honored with presentations on Wednesday as well:

Norman & Judy Adams, Adams Bluegrass Festivals

Darrel & Phyllis Adkins, Musicians Against Childhood Cancer

Darol Anger, fiddler/educator

Wayne Rice, San Diego’s KSON “Bluegrass Special” host

and Jack Tottle, band leader and educator at East Tennessee State University.

The Momentum Awards, handed out via video ceremony on Tuesday, September 29, focus on artists and industry professionals who are in the early stages of their bluegrass careers and the mentors who have helped them reach their young success.

The Momentum Awards recipients:

Industry Involvement

Kris Truelsen

Mentor

Annie Savage

Instrumentalist (2 recipients in this category)

Thomas Cassell

Tabitha Agnew

Vocalist

Melody Williamson

Band

The Slocan Ramblers