(Editor’s Note: This interview first appeared in full on Basic Folk. Listen on BGS or wherever you get podcasts. The following has been lightly edited for flow and clarity.)

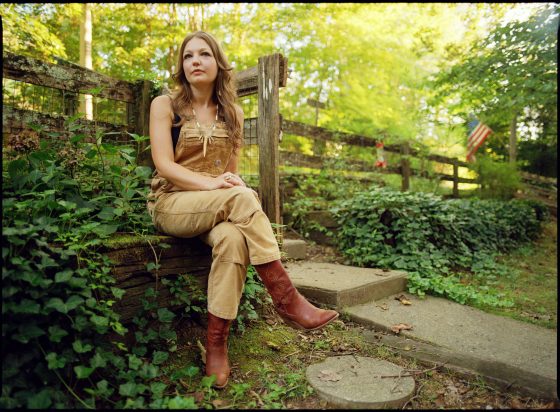

Jobi Riccio has only begun to scratch the surface of what they have to offer on their debut album, Whiplash. The songwriting is centered around self discovery and mourning past lives, laid alongside super-smart country and pop melodies. Our hero grew up an outdoor kid amongst the woods of Red Rocks Parks Amphitheatre in Colorado.

A strong bluegrass community encircled her playing from a very young age in a way that encouraged her to pursue music as a career. She spent time in Boston attending Berklee College of Music, nestled in the folk community centered around the historic venue Club Passim. March 2020 hit. Jobi had to leave her newfound community and found herself back in her childhood bedroom.

While wrestling with all the complications of finding herself and her place in the world, they were letting go of their childhood and the sense of grounding that came with it. Eventually, they made their way to Asheville, North Carolina to work on Whiplash.

In the studio, she took her time making the album and discovered that indeed, she had a strong sense of vision for the music. The trust of her collaborators allowed her to trust in herself and create an album that is turning heads and making Jobi Riccio one of the most exciting young songwriters of 2023.

BGS: Thank you so much for being on Basic Folk.

Jobi Riccio: Thank you for having me.

Alright, let’s start. I wanted to talk about identity and give you the opportunity to talk about your identity, like how do you identify pronouns, orientation, any of that stuff that we want to address.

JR: Yeah, I use she/they pronouns. I identify as queer and identity has been something that feels like it’s been important and very complicated for me. It feels like something that I have spoken about and made a part of my career, and now I’m kind of feeling, a little bit, like it’s become too much of a focus in my career, actually.

It’s funny, because I was listening to your other podcast that [you do], I can’t remember–

It’s [Basic Folk Debate Club], an occasional crossover series with Why We Write.

Yes! I was like, you’ll know the person to plug – and I’m so sorry to Why We Write.

It’s based on actually something that Lizzie No was saying. I just really resonated with something that she said, which was it’s about who is asking those questions of me. It can feel like a fine line. It’s kind of “cool” right now to be a queer artist or a Black artist or an artist of color in the folk space.

When you’re with your community, that feels one way, or with people who are truly great. And then when you’re with people who it just seems like they need to check that box. It’s so obvious and it’s so painful and it feels like a betrayal of yourself. And [Lizzie] put it a lot more eloquently than all that, but if we’re really going down the discussion of identity, it’s important to me that I am open with my identity, but I also feel like there have been times where it’s been so hyper-focused on. In a way that it’s like, “Did you even listen to any of my songs or did you know what I mean?”

I really enjoyed that answer. Doing these interviews, sometimes I feel like I’m gonna ask and I think that the interview is gonna go one way or a question is gonna go one way and it goes the complete opposite way. I just get to enjoy the ride.

You are from Morrison, Colorado, which is outside of Denver – the same place as Red Rocks Parks and Amphitheatre. You were an outdoor kid. How do you think your early experience in nature has impacted the person you became?

I think that it’s something that I really value and need and it’s a processing tool for me, being out in nature. It’s almost equivalent to songwriting and writing in my journal. It’s honestly super hard here in Nashville, because I don’t feel like I can get that, in the way that I used to be able to walk to a hiking trail five minutes from my house. I was absolutely supremely spoiled with outdoor access as a kid. [I didn’t] know any better. Like, there’s going to come a time where you’re going to live somewhere the nearest mountains are two and a half hours away. That is rough. It’s something I have to really intentionally build into my life now.

I think that nature heavily informs me as a person. Musically, I feel like it shows up in my lyrics [and] images from home, talking about coyotes and cactus and etc. I feel like it’s so intrinsic to who I am as a person.

So nature ruined you.

For real. The nature ruined me. Colorado ruined me.

There has always been this strong draw to music for you – country radio, your parents and sister’s collection of music, and also making music on your own. Can you set the scene for what music looked like in your house? And when did you get a grasp on your own taste in music?

My parents definitely – we had like a home stereo and a big collection of CDs and I spent a lot of time just sort of putzing around my house as a little kid, opening cabinets, and looking at things and opening the encyclopedia and reading. I don’t know if anyone else feels like a really intrinsic part of childhood was just looking at things.

The CD collection in like, a big wicker basket was definitely a huge one for me. They felt like little gifts. I could open up the CD and then there was this extra thing I could pull out and there were liner notes and lyrics and I could read along. That was really big for me, because I was always really interested in lyrics.

My dad’s a huge Bruce Springsteen fan. We love the Boss and sometimes we can’t understand the Boss. And like, his lyrics are wonderful, too. I really feel like that was pretty formative to me, looking through my parents’ CDs and my sister’s CDs as well. My oldest sister had like a clear, hot pink, very early 2000s lockbox thing that she kept her CDs in. I very vividly remember going into her room and stealing CDs – The Killers, Coldplay, A Rush of Blood to the Head was a big one for me, Sheryl Crow, Tuesday Night Music Club, Yellow Ocean Avenue. Then like Emmylou Harris, Bruce Springsteen, Linda Ronstadt, the Eagles, James Taylor.

There is a strong bluegrass community where you’re from. You found it at an early age, playing mandolin when you were like eight or nine years old. Since then you’ve sought out musical community, so what did you learn from that first musical community?

The bluegrass community was a big part of feeling supported for me in music. I was always a kid who sang and was like, the girl with a good voice in like my elementary school class or whatever, but I didn’t see myself as a musician until I really started playing mandolin. I had a teacher and he was super supportive and was like, “You’re really great at instruments, too.”

I feel like the bluegrass community in my hometown took me seriously even though I was a little kid running around at RockyGrass – and by “a little kid” I mean 16. I didn’t go to my first bluegrass festival until I was a teenager. I would go and sit and jam with adults and be taken seriously. I really looked up to [those who were] offering their support to me, that was immeasurable to [growing] my own self confidence at that age.

I mean, I was so insecure at like 15, 16. The first year I ever went to RockyGrass, which sort of became my home festival, I didn’t even go out and play with anyone. I just sat in my camper with my mom, because I was so scared and so nervous and having trouble with confidence. The next year, I was out like playing every night ’til like 2 or 3 a.m.

That’s a huge shift!

Yeah. I feel like community and music– I mean, no musician is an island. We’re nothing without the musicians who came before us and those who’ve supported us. Sometimes I look back on that time and wonder if I hadn’t gotten that nod in that jam from that older kid who was really good, who I thought was awesome; or from that artist who I worshipped, who told me I had a beautiful voice; or I had shared one of my songs with them, and they were encouraging of me writing. I wonder if I would have taken it this far?

Then I got to be in a really beautiful community space working at Club Passim in college, too. That also further helped bolster my confidence, especially playing solo. Because – as you know, as also somebody who worked there in a much different capacity – it’s very much like a solo listening room, singer-songwriter space.

I play solo [a lot] now on tour, because I can’t afford to bring out a band. I feel like I really garnered some valuable skills watching other people like Mark Erelli and Lori McKenna play solo at Passim and also having to do that myself, learning how to speak about the songs I had written and not be painfully awkward, but doing that in the loving embrace of that room.

You’ve talked about Sheryl Crow and The Chicks as having a huge impact on you. You picked up the mandolin after you first heard Nickel Creek – can you talk more about the influence Chris Thile and Sara and Sean Watkins had on you?

So, I first heard Nickel Creek on the radio on KBCO, which is like the AAA station.

Hell yeah, that’s a huge station. That’s where AAA was born!

Where AAA was born, famously, yes! That was my local radio station that I listened to as a kid. And they would play “Smoothie Song” by Nickel Creek. This was around the same time that I heard the Home album by The Chicks. I was listening to Top 40 country music and also hearing mandolin here and there. It’s so strange, because I don’t play the mandolin anymore. It’s just something I’m not interested in now – it makes me almost kind of sad to think of how this was such a big part of my life.

Then I really pivoted – and it’s like, I’ll never say never, but yeah, I started playing mandolin when I was 15, I wanted to play mandolin when I was about eight or nine years old, because that was when we got Why Should the Fire Die on CD as a family. When I started opening up the CD and reading the booklet and listening – that album is so cool, because there’s a little bit of almost a pop-punk thing to some of the songs, like “Somebody More Like You.” That was so of-the-time and I loved it. I couldn’t get enough of that.

Being introduced to this new palette of instruments that I really hadn’t heard played in this way. I was familiar with bluegrass to some extent, but it like bluegrass for me and my like angsty little 12-year-old self. And, you know, everybody’s angsty selves at any age. That struck such a chord in me…

The first song I heard by them was that Pavement cover.

And Pavement’s super emo! “Spit On a Stranger,” right?

Yeah, that’s it.

I loved that album, too. They were all older than me, but I didn’t really know that either because, like, they’re pretty young on the CD case. They’re probably [around] my older sister’s age, who is now 28. They’re not that close in age to me, but I did feel a kindred-ness that I feel like a lot of roots artists talk about, hearing them and the Chicks and being like, “Oh, this is cool! This is of the moment.” They’re incorporating sounds that we like from other genres, which is really what I think I’m trying to get with the whole pop-punk thing, though I know that can be kind of a “dirty” word, like pop country. I don’t think it should be, I don’t think any genre word should be.

And I definitely had like a three month period where I was like, “I’m in love with Chris Thile. I’m going to marry him.” That was a little, you know, short lived, but it was strong. His high, angelic voice really spoke to my prepubescent soul.

That’s so sweet.

You’re like, “I don’t know what to say about that!”

Thank you for sharing. No, it turns out it was Sara Watkins the whole time!

Right, yeah! Hiding in plain sight!

Your bluegrass wife.

(Editor’s Note: Listen to the unabridged Basic Folk episode featuring Jobi Riccio here.)

Photo Credit: Monica Murray