Hurricane Helene tore through Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Virginia, and beyond in late September, 2024, leaving a wide wake of devastation and destruction from her high winds, record rainfall, and historic flooding. Central and Southern Appalachia and the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina, Southwest Virginia, and East Tennessee were hit especially hard, experiencing what some experts have called a 1,000-year weather event. Due to the particular nature of the geography and topography in the mountains, communities of all sizes – from Boone and Asheville, NC to tiny Chimney Rock and Lansing, NC to Erwin, TN and Damascus, VA – were hit especially hard by flash floods, downed trees, landslides and mudslides, impassable roads, and utility outages.

Slowly but surely over the last ten days, as cell service, power, and communication are restored in a slow trickle to the hard-hit and hard-to-access area, more stories, photos and videos, and first-hand accounts have been disseminated from survivors of Helene’s fury. Their accounts are truly harrowing. The damage nearly unparalleled in recent memory.

Central and Southern Appalachia are a region rich in musical and cultural heritage, with so many of America’s quintessential roots music forms being hugely influenced by these mountains and their neighboring locales. Asheville and Boone are two gems in the American roots music scene and so many smaller towns in the tri-state area have their own bustling arts economies, as well. Musicians, songwriters, and creators from all corners of the BGS family reside in this part of the country; watching from afar as they recover their destroyed lives and livelihoods, build community, support each other, clean up the mud and debris, and act in pure solidarity has been both encouraging and heart-wrenching.

For those of us who adore the Blue Ridge, Appalachia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia but live elsewhere, it’s been a nearly constant questioning of, “What can we do to help?” since the storm hit. Especially, what can we do to aid our fellow roots musicians in Helene’s track as they rebuild their lives? Gratefully, resources, tips, donation links, volunteer oppportunities, and more have been pouring in as the mountains and neighboring areas come back online.

Below, we gather a few events, donation links, GoFundMes, resources, and more – for folks in and outside of the region – to lend their support to our friends and neighbors whose lives have been forever altered. While we hasten to rebuild and recover, we also hold immense love, care, and grief for all of those who are still missing, unaccounted for, and presumed deceased in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene.

The road to a “new normal” across the southeast, from Florida’s Big Bend to Virginia’s Crooked Trail, will span months and years, if not decades. The only way we’ll get there is by supporting and caring for each other – and that support starts now.

Sturgill Simpson’s North Carolina Benefit Show

Mainstream country outlaw Sturgill Simpson has just announced his Why Not? tour – featuring his new project and persona, Johnny Blue Skies – will hold a special North Carolina Benefit Show on October 21 in Cary, North Carolina at the Booth Amphitheatre with all proceeds benefitting the North Carolina Disaster Relief Fund. Tickets go on sale this Friday, October 11 at this link. As explained in a press release announcing the event, Simpson was originally scheduled to perform at Asheville’s ExploreAsheville.com Arena on the same date, but due to the devastating impact of the storm, that show has been canceled. This quick-pivot rescheduled benefit show is just another indicator of how important North Carolina is to country and roots musicians.

Help Musicians Hasee Ciaccio and Abby Huggins Rebuild

View this post on Instagram

Hasee Ciaccio is a bluegrass bassist who has toured and performed with Molly Tuttle, Sister Sadie, Laurie Lewis, Alice Gerrard, AJ Lee & Blue Summit, and many, many more bands and acts in bluegrass, old-time, and string band music. She and her spouse Abby Huggins, a community builder, dancer, and artist, lost their home to Hurricane Helene-caused tree falls and mudslides.

The California Bluegrass Association has begun a fundraiser to help Hasee and Abby rebuild, as they must continue paying a mortgage on a home that became unlivable in an instant. The outpouring of generosity has been overwhelming, with 60% of their goal already being reached in the short time since the hurricane struck on September 27. Visit the CBA here in order to read more and donate to support Hasee & Abby.

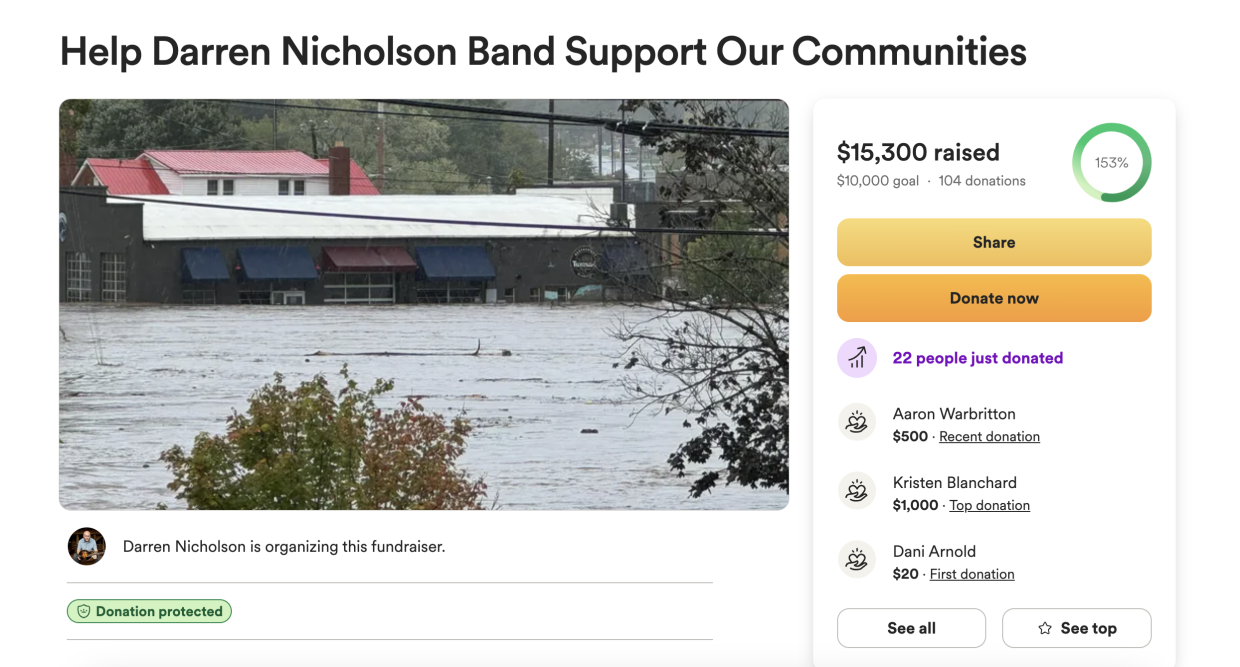

Mandolinist Darren Nicholson and Band Pitch In

Darren Nicholson is a mandolinist, songwriter, and Western North Carolina native who knows first hand how floods of this nature can uproot entire lives and communities. In 2021, his home turf, Haywood County, was devastated by flooding from a tropical depression. He led recovery efforts then, and he’s pitching in again now – with his entire band pulling their weight to bring GoFundMe donations, supplies, and resources to their own communities in Western NC and East TN.

“The entire band is out serving their communities at this time,” Nicholson shares in the GoFundMe description. “Avery is a first responder doing search and rescue; Aynsley is distributing supplies in Unicoi, TN; Kevin is distributing water and fuel; Darren is cutting trees and distributing supplies in Haywood County, NC.”

If you’re able, you can give directly via GoFundMe to support Darren Nicholson and his band bringing glimmers of hope to their impacted communities. They’ve already exceeded their fundraising “goal” – and the dollars raised back in 2021 – but there is still much work to be done, so consider donating if you can.

BGS Contributor and Music Journalist Garrett Woodward Reports From on the Ground

Frequent BGS contributor and freelance music journalist extraordinaire Garrett Woodward has been reporting – for RollingStone and others – from on the ground in the region about the impact on Asheville, North Carolina’s musicians and beyond. Despite dealing with power and internet outages himself, Woodward has been shining a light on the experiences of those dealing with the immense fall out of this storm.

We so appreciate Garrett keeping all of us in the loop with what’s happening on the ground, while spreading the word about relief efforts, resources, and donation pages. All of his stories above include many ways to give and to show up for North Carolina, so dig in and get involved.

Donate to the IBMA Trust Fund

View this post on Instagram

Hurricane Helene hit during IBMA’s World of Bluegrass business conference and IBMA Bluegrass Live! festival held in Raleigh, North Carolina. While the disruption to the event was not insignificant, the organization immediately began messaging more broadly about the impacts to the region and the destruction just down I-40, in the western parts of the state, in Tennessee, and Virginia.

Before the festival had even concluded, IBMA began fundraising through their Trust Fund, which supports bluegrass musicians and professionals facing hardships – whether financial, medical, disasters, etc. Members of the IBMA and its staff and board even already held a benefit livestream show. You can watch that performance here, and donate to the Trust Fund at any time as it supports bluegrass community members in need.

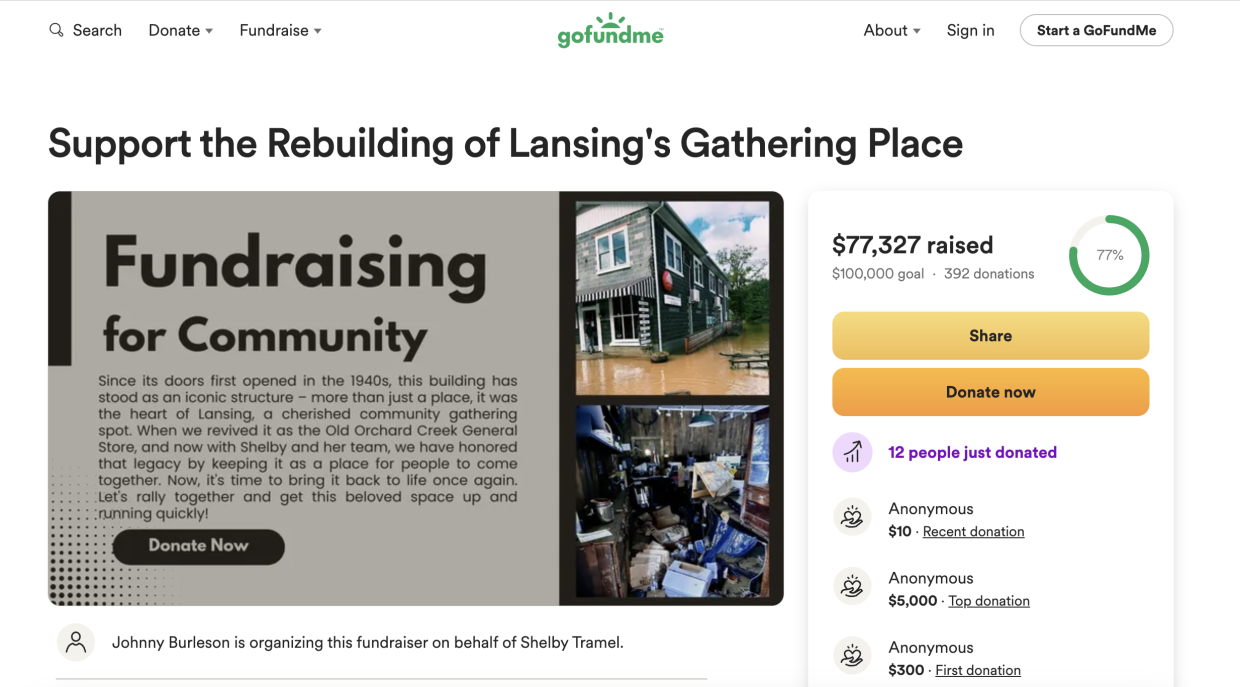

Help Ola Belle Reed’s Hometown Rebuild

Ola Belle Reed’s hometown of Lansing, North Carolina is nestled in the mountains of Ashe County alongside Big Horse Creek. As you drive into the tiny village from the south, you’ll encounter a brightly colored mural of Reed on a local store’s brick wall, a bright barn quilt accenting a gorgeous portrait of this iconic old-time and bluegrass legend. Unfortunately, Helene took its toll on Lansing’s adorable little downtown too, flooding nearly every business and destroying homes, bridges, and livelihoods.

The Old Orchard Creek General Store, a newer business that had become an important community keystone and gathering place in its few short years of business, was almost entirely destroyed. The store is known for hosting nearby and regional musicians – like Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer, Martha Spencer, Trevor McKenzie & Jackson Cunningham, and many more – on their porch and in their cute cafe, supporting dozens of area artists with a quality local gig. You can donate to support the general store’s rebuild here.

In addition, Lansing and the Ashe County area surrounding it are criss-crossed with mountain creeks and streams, many of which burst their banks and washed out bridges, driveways, and crossings that were critical for folks’ daily lives and safety. As a result, the citizens are banding together to rebuild this critical infrastructure for their neighbors. Give to help rebuild their roads, bridges, and driveways here.

Woody Platt’s Album Release Becomes Rescue Carolina

View this post on Instagram

Many folks are synonymous with the Western North Carolina music scene, but perhaps no single person epitomizes what it means to be a musical community member in Western NC like Woody Platt does. With a new album, Far Away with You, dropping this Friday, October 11, Platt has re-tooled his album release show to be a benefit for Rescue Carolina, raising money for local relief efforts in Brevard, NC and nearby. A bastion venue in the area, 185 King Street, will host the show – and they’ve been pitching in quite a bit with recovery themselves, too. Everyone is pitching in!

Not in the region? You can purchase a livestream ticket and still show up for Woody Platt and for Rescue North Carolina. Give directly to their GoFundMe here.

Star-Studded Concert for Carolina

Announced yesterday, October 7, with tickets going on sale Thursday, October 10, Charlotte, NC’s Bank of America Stadium will be taken over on October 26 by Luke Combs, Eric Church, Billy Strings, James Taylor, Keith Urban, Sheryl Crow, and more for a star-studded benefit show. Proceeds will support relief efforts in the Carolinas. The event will be hosted by ESPN’s Marty Smith and Barstool Sports’ Caleb Pressley and will feature additional artists still to be announced. It’s sure to be a sell out – and for good reason!

Get more information and purchase tickets here.

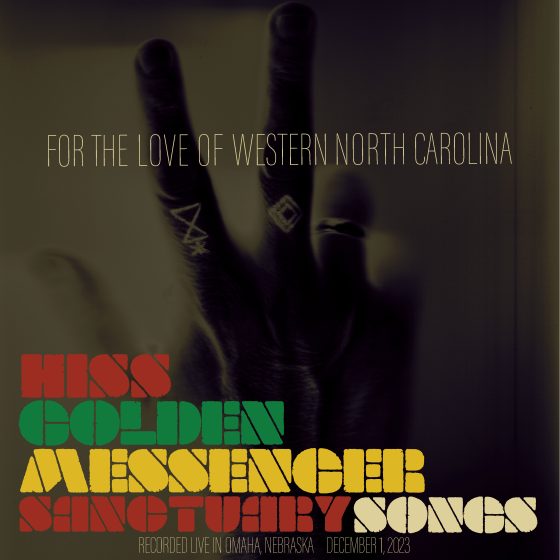

Hiss Golden Messenger Dedicates Sanctuary Songs: Live in Omaha, NE to Western North Carolina

North Carolina-based indie, folk, and Americana artist Hiss Golden Messenger (AKA M.C. Taylor) has announced his upcoming live album, Sanctuary Songs: Live in Omaha, NE, will benefit BeLoved Asheville, a local organization raising funds for relief efforts. The 18-song project is available for purchase now exclusively via Bandcamp.

“Western North Carolina is really, really hurting, y’all,” Taylor noted on Instagram. “We don’t even know the half yet, and I’m glad to be able to help.”

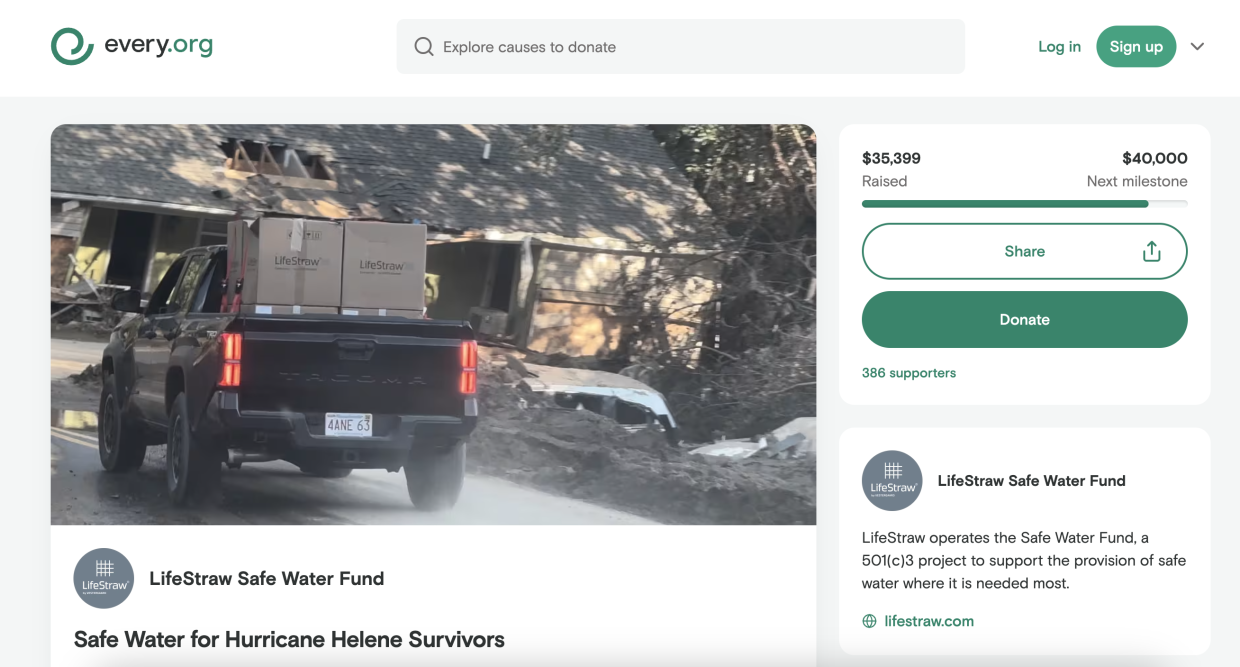

Safe Water for Hurricane Helene Survivors Via LifeStraw

LifeStraw is a brand all about safe, clean water for all. Their products are popular with hikers, campers, outdoors people, and folks with limited access to clean water around the world. After Helene, the company activated their Safe Water Fund and their disaster response teams to bring their filtration products to those who’ve lost access to clean water. Donating directly to the fund helps bring their large purifier systems like the LifeStraw Community and LifeStraw 8L to the region as well as their LifeStraw Home pitchers and dispensers for use in homes and personal bottle and straw filters for individual use. Get more info and donate here.

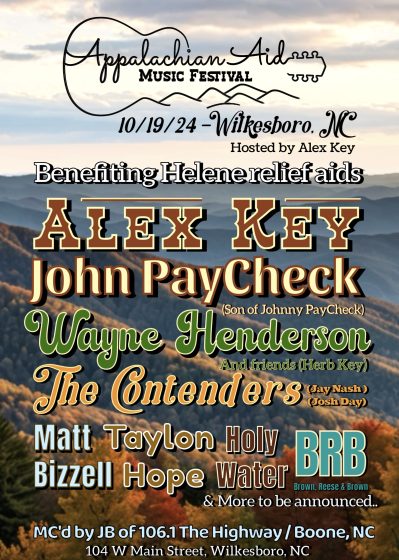

Appalachian Aid Music Festival

On October 19 in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, the Appalachian Aid Music Festival will feature performances by host Alex Key, John PayCheck (son of Johnny PayCheck), local great Wayne Henderson, and many more. The event will benefit Musicians Mission of Mercy, a non-profit embedded in rural Western North Carolina, specifically in Ashe County. Tickets are available now via Eventbrite, but first responders – nurses, doctors, firefighters, linemen, EMS, etc. – should know they’ll be admitted for free with their work IDs.

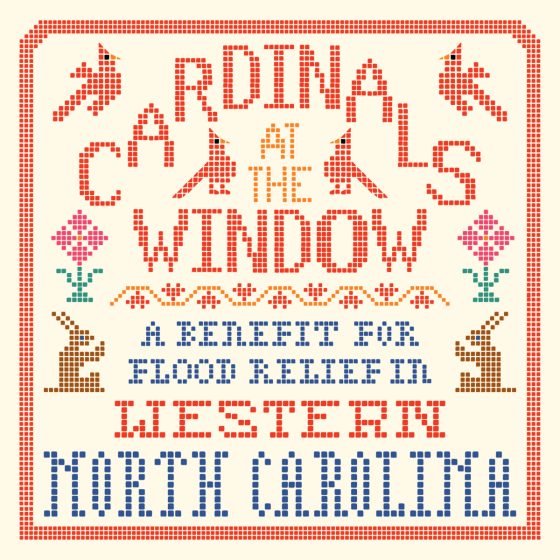

Cardinals At The Window Compilation Album

Released on October 9, Cardinals At the Window is a gargantuan compilation album of 136 tracks – yes, you read that right, 136 – submitted from various artists from across the roots music landscape. The project will benefit three non-profits based in Western North Carolina administering hurricane relief, Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, Rural Organizing and Resilience, and BeLoved Asheville. Compiled by Libby Rodenbough, David Walker, and Grayson Haver Currin, the album is available exclusively via Bandcamp and features tracks from amazing artists like Gillian Welch & David Rawlings, Hiss Golden Messenger, Watchhouse, Calexico, the Decemberists, Iron & Wine, MJ Lenderman, Mipso, Jason Isbell, Tyler Childer, Waxahatchee, Yasmin Williams, and many, many more.

Purchase the project and support the cause here.

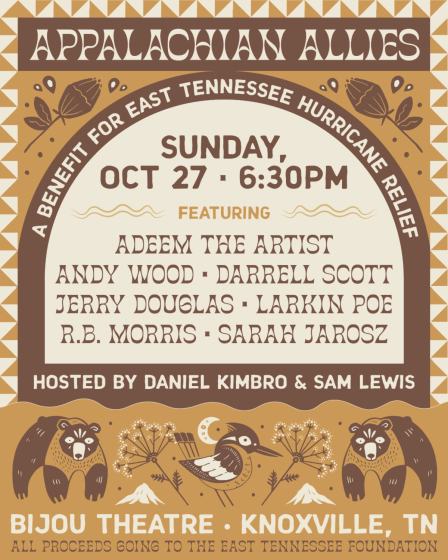

Appalachian Allies

On October 27 at the Bijou Theatre in Knoxville, Tennessee an impeccable lineup of roots musicians will gather to raise funds for the East Tennessee Foundation, a non-profit committed to supporting flood victims and flood relief programs in the mountains of East Tennessee. Hosted by bassist Daniel Kimbro and singer-songwriter Sam Lewis, the event will feature performances by Adeem the Artist, Darrell Scott, Jerry Douglas, Larkin Poe, Sarah Jarosz, and more. Tickets are on sale now. Make plans to support Tennesseans by showing up and showing out for Appalachian Allies on October 27.

“Hell in High Water” – Mike Thomas

Singer-songwriter Mike Thomas grew up in East Tennessee. After Helene tore through his home state, the Carolinas, and Virginia, he began writing “Hell in High Water” in early October.

“For generations, my family has called East Tennessee home, and although I have lived in Nashville for 20 years, I will always be an East Tennessean. Watching the aftermath of Helene unfold affected me deeply…” Thomas said via press release. “I couldn’t get those heartbreaking stories and images out of my mind.”

So, he wrote “Hell in High Water,” recorded it in record time, and released the track with all proceeds going to Mountain Ways, a non-profit committed to providing ongoing hurricane relief and assistance in the region. “I started writing ‘Hell in High Water’ on October 4th and finished it on October 6th,” Thomas continues. “I played it for some close friends and family who urged me to record and release it as soon as possible. I sent it to my producer, Tres Sasser, and my bandmates. Everyone dropped what they had planned to record the track on October 17th. There was a sense of urgency and purpose to get the song done and to get it done right.”

The song is now available to stream via Spotify, Apple, and more. Listen to the track below. All proceeds will go to hurricane relief. Listeners and fans can also donate to Mountain Ways directly here.

Our Co-Founder, Ed Helms, Agrees

View this post on Instagram

Even our co-founder himself, Ed Helms, took to social media to point out how special and important this region of the country is to all of us – BGS and beyond. Like many of us, Ed has had a lifelong relationship with the mountains of Western North Carolina and he understands personally how difficult this recovery process will be. You can find all of the links he mentions in this clip and more below.

Whatever you have to give and contribute to rebuilding after this storm, nothing is too small or insignificant. It will take all of us to rebuild Central and Southern Appalachia and the entire Southeast post-Helene.

Give to the Appalachian Funder’s Network here.

Give to World Central Kitchen here.

Support Operation Airdrop, Concord, NC

For more donations to local, vetted organizations, Blue Ridge Public Radio has compiled this list.

(Editor’s Note: Have a fundraiser, link, benefit concert, or similar hurricane recovery resource you’d like us to share here? Email us at [email protected].)

Photo Credit: Courtesy of NASA Image and Video Library. Sept. 25, 2024 – Hurricane Helene is pictured from the International Space Station as it orbited 257 [miles] above the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Mississippi.