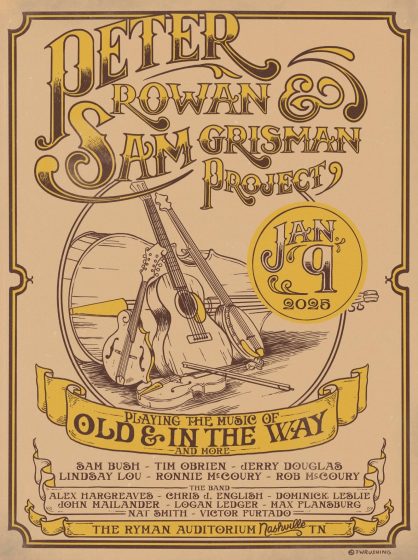

On January 9, 2025, there will be a special performance – more so a once-in-a-lifetime celebration – of the groundbreaking music of Old & In the Way at Nashville’s famed Ryman Auditorium.

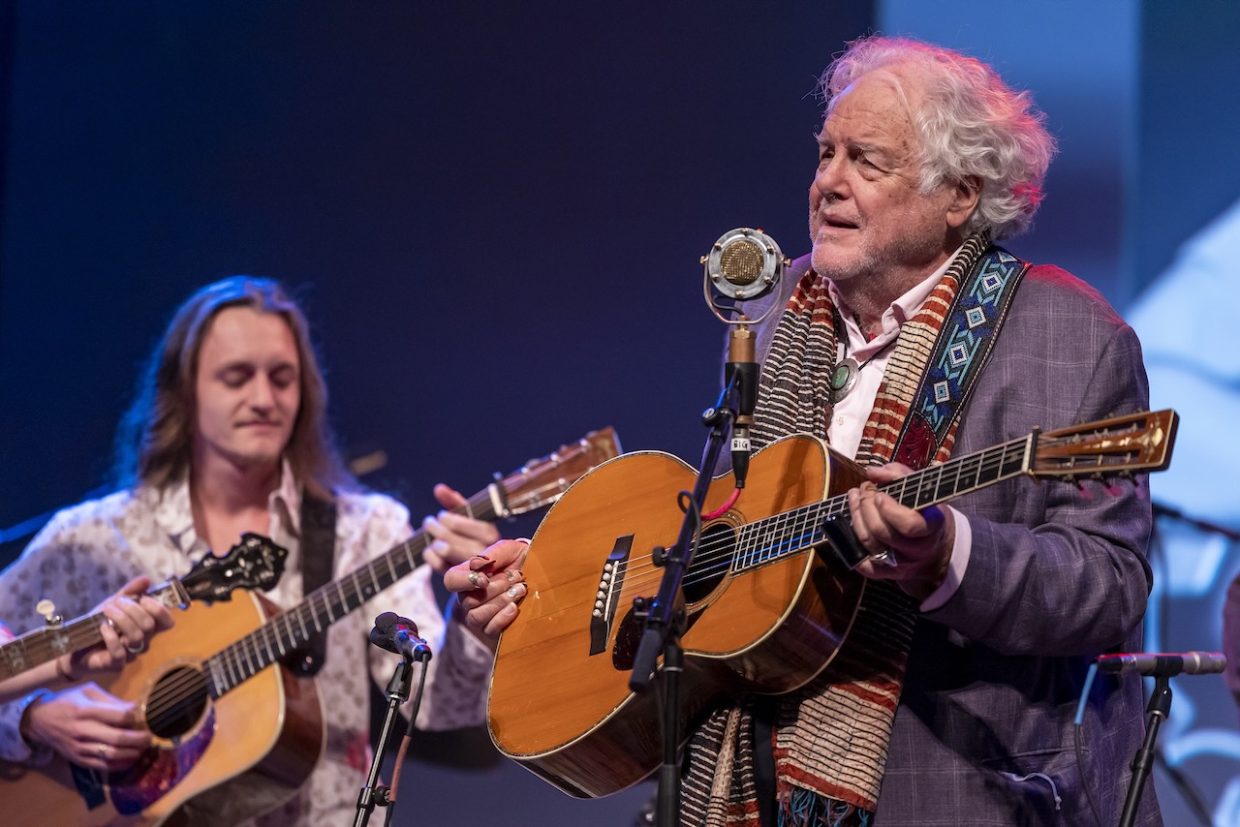

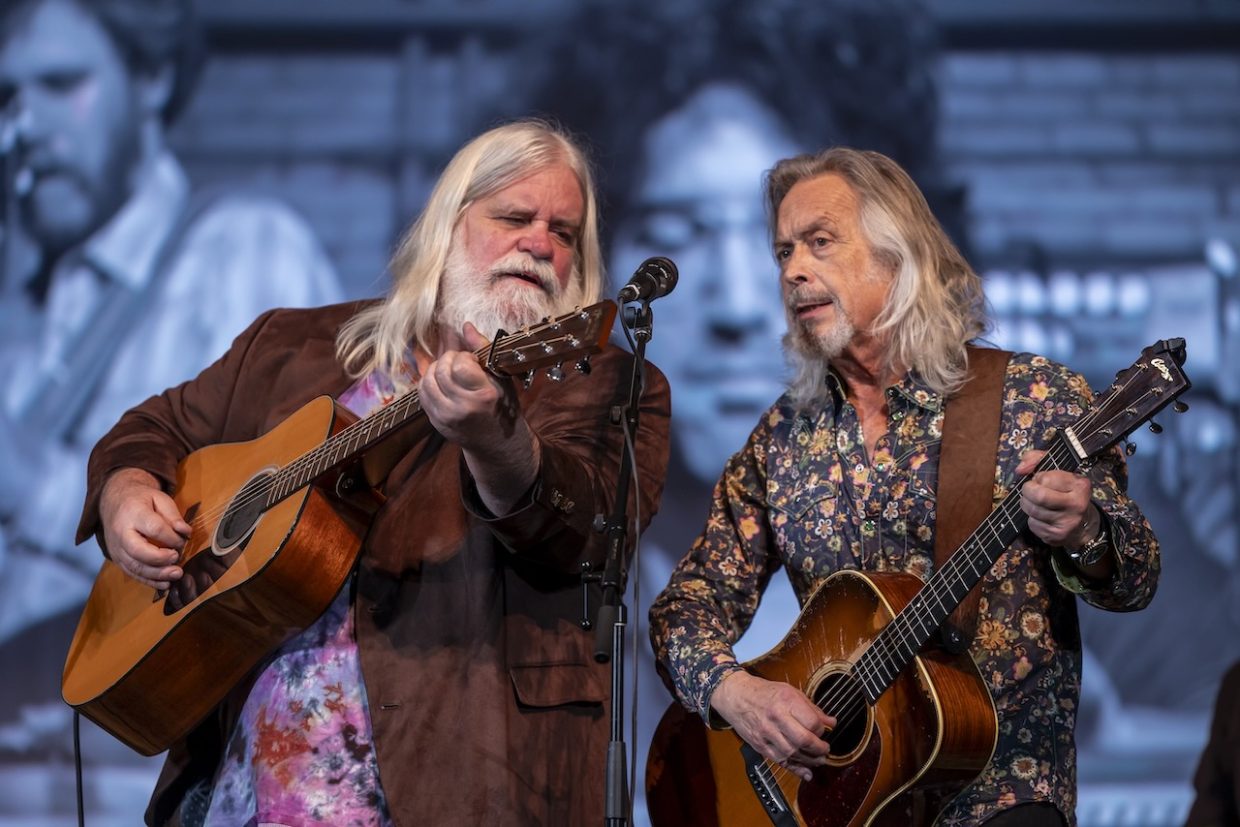

Led by the “Bluegrass Buddha” himself, Peter Rowan, the legendary singer-songwriter and founding member of the group will be backed by the Sam Grisman Project. The gathering will also feature a murderers’ row of talent: Sam Bush, Tim O’Brien, Lindsay Lou, Ronnie & Rob McCoury, and more.

“In bluegrass, you just do the beautiful grace of presenting the music, being good neighbors and all that stuff,” Rowan told BGS in an exclusive 2022 interview. “But you could hear us in the band going, ‘go, man, go.’ Go for it, that’s where we came from. That’s what Old & In the Way was – the ‘go for it’ signal to everybody.”

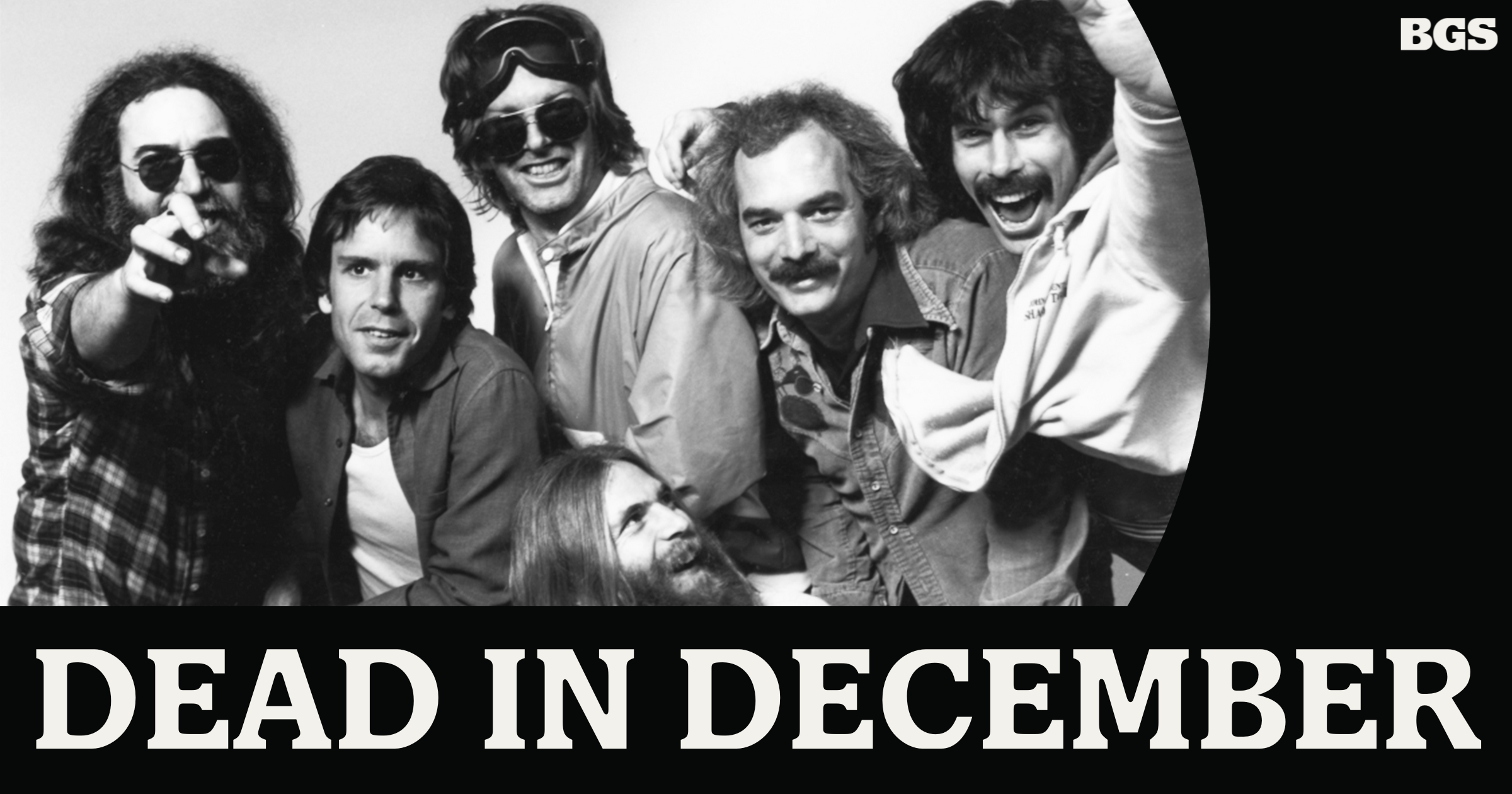

To preface, Old & In the Way started as impromptu pickin’-n-grinnin’ sessions in the early 1970s between Rowan, his longtime friend, mandolin guru David Grisman, and Jerry Garcia, iconic guitarist for the Grateful Dead, who reached for his trusty banjo during the gatherings at Garcia’s home in Stinson Beach, California.

“We started picking every night after supper [at Jerry’s],” Rowan remembers. “We went through old song books and learned a bunch of material.”

At the time, Garcia was searching for new avenues of creative exploration, seeing as the Dead were in the midst of taking a much-needed hiatus after years of relentless touring and recording. He was also, perhaps subconsciously, trying to tap back into his roots before the Dead, this landscape of the late 1950s/early 1960s where Garcia was heavily involved in the San Francisco Bay Area folk scene.

“And you realized that Jerry was an intergalactic traveler, just dropping in on the Earth scene for a little while, but he was totally at home,” Rowan says of Garcia’s restless penchant and lifelong thirst for acoustic music.

When Old & In the Way formed in 1973, the trio recruited bassist John Kahn, as well as a revolving cast of fiddlers (Richard Greene, John Hartford, Vassar Clements). Sporadic gigs were booked around the Bay Area, with the vibe of the whole affair casual in nature – the ethos one of camaraderie and collaboration, but without expectations or boundaries.

“I remember singing the ending of ‘Land of the Navajo’ at the first rehearsal and I looked over at Jerry,” Rowan recalls. “He kept nodding his head like, ‘go.’ It was like Jack Kerouac at Allen Ginsberg’s poetry reading at City Lights Bookstore – ‘go, man, go.’ Encouragement, encouragement.”

By 1974, Old & In the Way simply vanished into the cosmic ether, but not before capturing a handful of live performances that have become melodic sacred texts of a crucial crossroads for acoustic music. To note, Old & In the Way’s 1975 self-titled debut album went on to become the bestselling bluegrass album of all-time – until it was dethroned by the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack released in 2000.

As it stands today, Rowan, now 82 years old, is the only remaining member of Old & In the Way still actively performing. Garcia, Clements, Kahn, and Hartford have all sadly passed on, with the elder Grisman and Greene retired from touring. Grisman’s son, standup bassist Sam Grisman, is now carrying his father’s bright torch.

And although the tenure of the Old & In the Way was short-lived, the ripple effects of the band’s ongoing influence and enduring legacy remains as vibrant and vital as it was those many years ago, when a handful of shaggy music freaks kicked off a jam that will perpetuate for eternity.

In preparation for the upcoming Old & In the Way showcase at the Ryman on January 9, BGS recently spoke with Sam Grisman, who talked at-length not only about his continued work with Peter Rowan and the intricacies of Jerry Garcia, but also why a band Grisman’s father started over a half-century ago still captivates the hearts and minds of music lovers the world over.

You were five years old when Jerry Garcia passed away. You were really young, but do you remember anything that you hold onto?

Sam Grisman: Yeah, I have a very vivid memory of what our house felt like, smelled like, and just what the energy was like when Jerry was around. And I remember that sort of ease, just the way that he made people feel. It seemed like my parents were at ease when he was around.

And he probably felt at ease being around them. It was probably a safe haven at that house.

Definitely. And, you know, my parents smoked weed in the house. But, my mom was pretty strict about cigarettes. [She] wouldn’t let anybody smoke cigarettes in the house. But, when Jerry was around, he smoked cigarettes in the house. So, part of this smell in my blurry five-year-old memory is the smell of cigarettes. And Jerry would sometimes wear a leather jacket, maybe the smell of leather.

I remember the sound of his laugh. I remember all that music, and some of it I remember so vividly that I just know that part of that memory is reinforced by being there as a little toddler when they were working up [music]. Because they would often work on tunes upstairs in the living room and then take them down to the studio, put them on the mics and pull them.

You just wanted to be around it all and soak it all in.

I was a really curious kid.

With the Ryman show coming up, there’s been a lot of celebration of Old & In the Way as of late, especially with you touring with Peter Rowan and the current Jerry Garcia exhibit at the Bluegrass Hall of Fame & Museum. You’ve been around those songs your whole life. But, when you think about the context of Old & In the Way, and what you’re doing at the Ryman, what really sticks out with why that was such a special time in not only bluegrass, but in the lives of those people?

I mean, what a lightning-in-the-bottle chapter of all those people’s lives, you know? I think 1973, ’73/’74, was a particularly fertile time for Jerry. He was playing a full schedule with the Dead. He had Jerry Garcia Band stuff. He was playing in Old & In the Way. He was playing pedal steel with the New Riders of the Purple Sage. It seemed like he really had an itch to go back to where his roots were, especially when you look at [the Grateful Dead album] Workingman’s Dead [that was released a] couple years prior.

For all of us, who are looking back on it 50 years in the future, it seems like this momentous, heady time that was just meant to be. But, for those guys in the moment, it was just total serendipity. And the quintessence of just going with the flow – Stinson Beach, California, vibes. They just kind of stumbled into this reality.

“Y’all wanna play?” “Sure, why not.”

Yeah, where it would just be really fun to have this bluegrass band that they didn’t take super seriously, which I think really comes across in the recordings, you know? Because there’s all this joy in that music that might not necessarily have been there if those guys were taking it super seriously or if they needed it to pay their bills. It was a very interesting circumstance.

And for them to call their hero Vassar Clements into the mix, on a sort of whim because Peter found his number on a card in his wallet. It was sort of like a fantasy camp for these guys. Like a bunch of hippies sitting around on the beach, smoking a joint, thinking: “Wouldn’t it be great if we had the world’s greatest fiddle player just show up?” “I bet you we could book a gig.” “Hey Jerry, you got these legions of people following you around, you could probably get us a gig, right?”

And that’s kind of how it happened. Those gigs were so magical, because they happened mostly for all of these Deadheads in Marin [County, California], for like 16 months or something.

So, if you really had your finger on the pulse of it and you were going to the Keystone [music club in Berkeley, California], to see [the Jerry Garcia Band] and you loved what the Dead were doing, you knew that they were going to take this time off, but you just saw Jerry the week before and he never took his guitar off. He just finished the [Jerry Garcia Band] set and walked backstage with his guitar on and was smoking a cigarette, and then you saw him 30 minutes later talking to somebody off the side of stage, still had his guitar on — you’re thinking, “Gee, this guy’s not going to stop playing music this year, so I better keep my eyes peeled for what’s next.” And they played all these little gigs mostly around the Bay Area — they kind of captured some lightning in a bottle.

With playing these Old & In the Way melodies not only throughout your life, but also extensively nowadays with Peter Rowan, what’s been your biggest takeaway on what makes those songs and the ethos/history behind them so special to you? What about in terms of musicality, technique, and approach?

It’s hard to articulate how special it is to be exploring these beloved songs that mean so much to so many folks, myself included, with Peter and a cast of some of my best friends and favorite musicians. It’s a catalog that’s got a lot of depth.

Old & In the Way would play anything from songs by bluegrass heroes like Bill Monroe, The Stanley Brothers, Reno & Smiley, and Jim & Jesse to Vassar [Clements], Jerry [Garcia], and my pop’s instrumentals, to the tunes that Peter was writing at the time, which are some of my absolute favorite songs ever written.

Songs like “Midnight Moonlight,” “High Lonesome Sound,” and “Panama Red.” Playing these tunes with Uncle Peter makes me feel connected to the times he spent with David and Jerry in Stinson Beach in the early ’70s.

I grew up in Mill Valley and loved going to Stinson Beach with my friends, so I have a pretty vivid image in my mind’s eye. They played tunes, hung out, relaxed, took in the sea breeze, smoked a bunch of great weed, and developed a highly individuated “West Coast” approach to playing and singing this bluegrass music that they all loved and respected so much.

And then, they called one of my bass heroes, John Kahn, and their fiddle hero, the inimitable Vassar Clements and gave the world about one glorious year – I think around 50 shows – of a rare and lovable breed of bluegrass.

So much of everyone’s personality comes through in the music, and you can hear their camaraderie in the recordings. I guess my biggest take away from getting to play this music with Peter is how important it is to bring your own approach to these timeless songs that we love, while still honoring what it is that makes us love them in the first place.

You’ve known Peter Rowan since you were born. But, what has this latest endeavor together meant to you, to play the Old & In the Way catalog to not only lifelong fans, but also a whole new generation of acoustic music fans and bluegrass freaks?

It means the world to me to get to spend some time out on the road sharing space and time in service of this music with Uncle Peter. Getting to meet all of these folks who care so much about this music and feeling their appreciation and gratitude for Pete has been truly special.

There are so many people from so many different ages and different walks of life for whom this music has been the soundtrack to many fond memories, and I’m honored to be one of them. It’s also been a joy to see fresh faces in the audience and some folks taking in this music with a new perspective.

In your honest opinion, what is the legacy of Old & In the Way when you place it through the prism of the history of bluegrass and the road to the here and now, especially this current juncture where the torchbearers are selling out arenas and creating this high-water mark for acoustic, traditional and bluegrass music?

For many folks who know and love the music of Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead, Old & In the Way has been their first exposure to bluegrass. So many people over the years have told me how listening to Old & In the Way led them to further explore bluegrass music and its roots and branches. And others have told me how it inspired them to become pickers and start bands of their own.

I think Old & In the Way has been pivotal in bringing a wider audience with a more adventurous musical palette into the bluegrass universe. The legacy of Old & In the Way is one of exploration and preservation, and they certainly paved the way for many of us to walk a similar path — honoring the music that we love, while exploring its boundaries and finding our own voices and approaches.

It’s wonderful to see my friend Billy Strings out there playing for so many folks on such a big scale simply being himself, playing his own songs with a great group of friends, and also honoring the material that made him the musician that he is — maybe that’s a part of the legacy of Old & In the Way.

Photo Credit: Elliot Siff

Poster Credit: Taylor Rushing