“Well, we’ve been here before…”

When Rushmere was released in March of this year – Mumford & Sons’ first album in seven years – critics noted its homecoming feel. The songs, the sound, the oh-so-yearning lyrics; they all combined to take the listener back to the beginning.

Tracks like “Malibu” and “Caroline” do not, perhaps, hit the wild highs of “Little Lion Man.” There’s a subtler expression at play in the album, reflecting an evolution from youthful exuberance to the quiet wisdom that only comes with experience. But a decade and a half on from Sigh No More, the band have clearly doubled back from their more experimental forays – 2018’s Delta; Marcus Mumford’s solo project, (self-titled) – to celebrate what brought them together in the first place. In Rushmere they had returned to their rootsy roots, and found peace there.

This month, the band heads back out on tour to Chicago, Philadelphia, Montréal, and more. In November, they’ll return to Europe, and ultimately to the UK, where their final leg will climax at London’s 20,000-capacity O2 arena. Months on the road this year and playing to sold-out venues have proven one thing: people still can’t get enough of them.

And yet the world is a very different place to when their debut album hit the shelves in 2009. When Mumford & Sons first toured Sigh No More, Barack Obama was President of the United States. In the UK, the biggest question on people’s lips was what Kate Middleton would be wearing at her royal marriage to Prince William.

Today’s social backdrop feels meaner, more fractious, less optimistic. Widening rifts in society have made it harder for people to celebrate shared values, even cherish the same moments together. Mumford have split with one of their own band members as a direct consequence of our rapid political polarization. What is it, then, that felt so fresh back then – and that still appeals today?

Matt Menefee first encountered the Mumford sound when his progressive bluegrass band, Cadillac Sky, were at their peak. “We were heading up out of Texas to play Telluride in 2010, and we played some gigs en route,” says Menefee. “So we’d stopped at a hotel, and there was Marcus on MTV, and someone said, ‘Oh, this band’s headlining the festival.’ Our lead singer already had the record and so we listened to it all the way up there.”

For a group of musicians that favored a raucous, punk rock vibe, Mumford’s gleeful-yet-soulful energy was something new. “We were like, ‘Oh man, this is something else!’” Menefee recalls. “To hear these cohesive, in-your-face anthems… it was raging. The melodies and the lyrics were beautifully crafted as well. It was a force that blew our guys away.”

Mumford’s Telluride set became an instant classic (it’s still spoken of in awe today). “It was just a party,” remembers Jerry Douglas, whom the band had asked to join them on stage. “The guys looked so excited. I’ve been to that festival so many times and you can get jaded. But I’m watching them jump up and down and I’m going, this is what it’s supposed to feel like.” He describes that electric closing set as one of the best he’s seen in Telluride’s 51 iterations.

Douglas is one of the many Americana musicians that Mumford and bandmates Ben Lovett, and Ted Dwane sought out to learn from in their early years and have built enduring relationships with. They included Douglas in their performance at the SNL 50th anniversary show, after he had recorded lap steel for Rushmere track “Caroline” – although he laughingly points out that it didn’t make the final mix. “It changed it, it took the band away from just sounding like themselves. I kind of Jackson Browne-ed them a little bit…”

Those collaborative relationships are one of the reasons that Mumford & Sons continue to matter, not least to the musical communities they’ve done so much to elevate. After their first meeting, Menefee became a regular guest artist with the band and has been their go-to banjo player since Winston Marshall’s departure. “You watch them interact with people,” says Menefee, “and they’re so humble, so sweet, so encouraging. They really look after everybody. They’re good, good dudes.”

In August, Mumford & Sons relaunched their Railroad Revival Tour, whose 2011 iteration involved travelling the Southwest in vintage trains alongside Old Crow Medicine Show and Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros. This summer’s rolling festival picked up where that one had left off, traveling between New Orleans and Vermont. The long list of musicians joining them on board ranged from Nathaniel Rateliff and Ketch Secor to Lainey Wilson and Molly Tuttle to Trombone Shorty and Chris Thile.

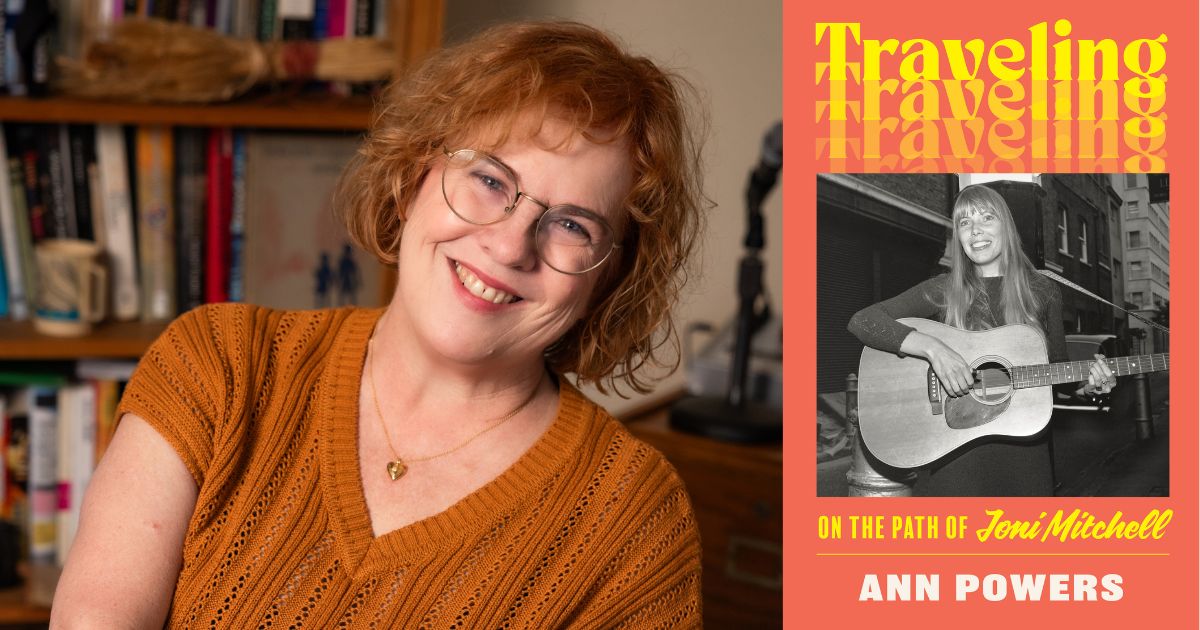

Lucius’s Jess Wolfe was one of the musicians sharing the stage with Mumford, after forging a bond with Marcus at celebrated, now infamous jams arranged by Brandi Carlile in Joni Mitchell’s living room. “Sitting listening to our hero sing – that’s such a humbling experience, it’s going to bring people close quite quickly,” laughs Wolfe. She describes Mumford & Sons as “natural collaborators – they feel like brothers from the minute that you step foot in the room with them.” It’s that comforting familiarity that expresses itself in their music and forms a major part of their appeal.

Having first heard their sound while working on the Brooklyn open mic circuit, Wolfe was struck by how it reflected the songs that her peers were writing, “except that these were songs that everyone could suddenly, with ease and without thinking, just sing along to. It was like a conversation you were having with an old friend.”

Their pulsing, anthemic melodies, underlaid with a signature stomp, quickly became an in-demand and much replicated sound in the industry. Banjo and mandolin players found themselves getting far more calls for session work. For musicians like Menefee who had spent years justifying their choice of instrument and trying to persuade a sceptical mainstream of its charms, the change was remarkable. “When Mumford hit, it was like, banjo’s cool!”

“I’d go do demo sessions for songwriters on Music Row and for years the publishers would ask you for ‘like, a Mumford thing,’” Menefee continues. “And I should say that’s not all they do – their Delta record is one of my favorites, with its beautiful marriage of electro pop and effects. But I witnessed the success of the other bands that followed in Mumford’s wake. They had a huge influence.”

Douglas believes it’s no exaggeration to say they changed the sound of the musical landscape. “And people either liked it or they didn’t. But it’s a heartbeat, you know? That’s the thing about it. It gets people excited and it makes them feel good. That endorphin rush happens and everybody goes to their happy place. And we need that right now. We need to go to our happy place.”

There, perhaps, lies the key to their successful return after seven years away from the limelight. Every night they play, Menefee sees crowds “losing themselves” in the singalongs. “There’s an anger and a vulnerability that really pierces the heart,” he says. “And it’s so freaking singable.”

The band themselves have admitted to be “stoked” to be headlining festivals in the UK again and there’s little sense of ego at their appearances. Instead, they host shows that have the feel of a party at which they themselves are enthusiastic guests. “It’s just so much fun,” says Menefee. “There’s a real joy in it, a rest from all the chaos.”

Perhaps, right now, we all need a bit more Mumford in our lives.

Photo Credit: Marcus Haney