Happy first Friday of November! Let’s kick off a month of new music round-ups with our first edition of our usual weekly collection for November.

To begin, banjoist Gena Britt – who you may know from Sister Sadie – releases her brand new solo album, Streets, Rivers, Dreams & Heartaches today. We’re sharing “What Kind of Memory Will You Be” off the new project to celebrate its launch. It’s one of Britts’ favorite tracks from the album. Her Sister Sadie bandmate, fiddler Deanie Richardson, is also included in our round-up today, joining fellow fiddler Kimber Ludiker (of Della Mae) on a twin fiddle rendition of a rip-roaring original instrumental, “No-See-Um Stomp.” It’ll have you dancing and smacking the hell out of some sandflies, too.

Singer-songwriter and guitarist Sammy Brue previews his upcoming album that pays tribute to one of his creative heroes, Justin Townes Earle, by crafting songs from inhabiting and being inspired by Earle’s journals. Brue wrote “Lonely Mornings” based on snippets of unrecorded lyrics in Earle’s journals, before Earle’s own recording of “Lonely Mornings” was released on ALL IN last year. The tunes stem from the same source, and feel connected, but show the intricate ways a single origin point can grow into two distinct songs. Watch the video for Brue’s “Lonely Mornings” below.

Our Missouri bluegrass pals the HillBenders bring us a brand new music video for their most recent single, a rock and roll and disco-infused string band version of Ola Belle Reed’s classic, “I’ve Endured.” The band leans into their genre-blending tendencies and highlight a couple of new members in the new studio music video, too. Plus, Americana-folk singer-songwriter Brendan Walter launches his new album, Disappearing Days, today and we’re sharing a new music video for his song “Pipe Dream.” Contemplating the realities and trials of building a career in the music industry, “Pipe Dream” and the album together demonstrate Walter’s goals in music are anything but far-fetched.

Make sure to check out a new single from guitarist-writer-archivist Cameron Knowler, as well, who covers Elizabeth Cotten’s “Wilson Rag” in a simple, pared-down arrangement featuring acoustic guitar, pedal steel, and kick drum. Knowler tweaks Cotten’s original arrangement slightly, continuing the age old tradition of musical transfer and cross-pollination in bluegrass, old-time, and beyond.

It’s quite a nice round-up to get the month rolling, isn’t it? Check it out for yourself below, ’cause You Gotta Hear This.

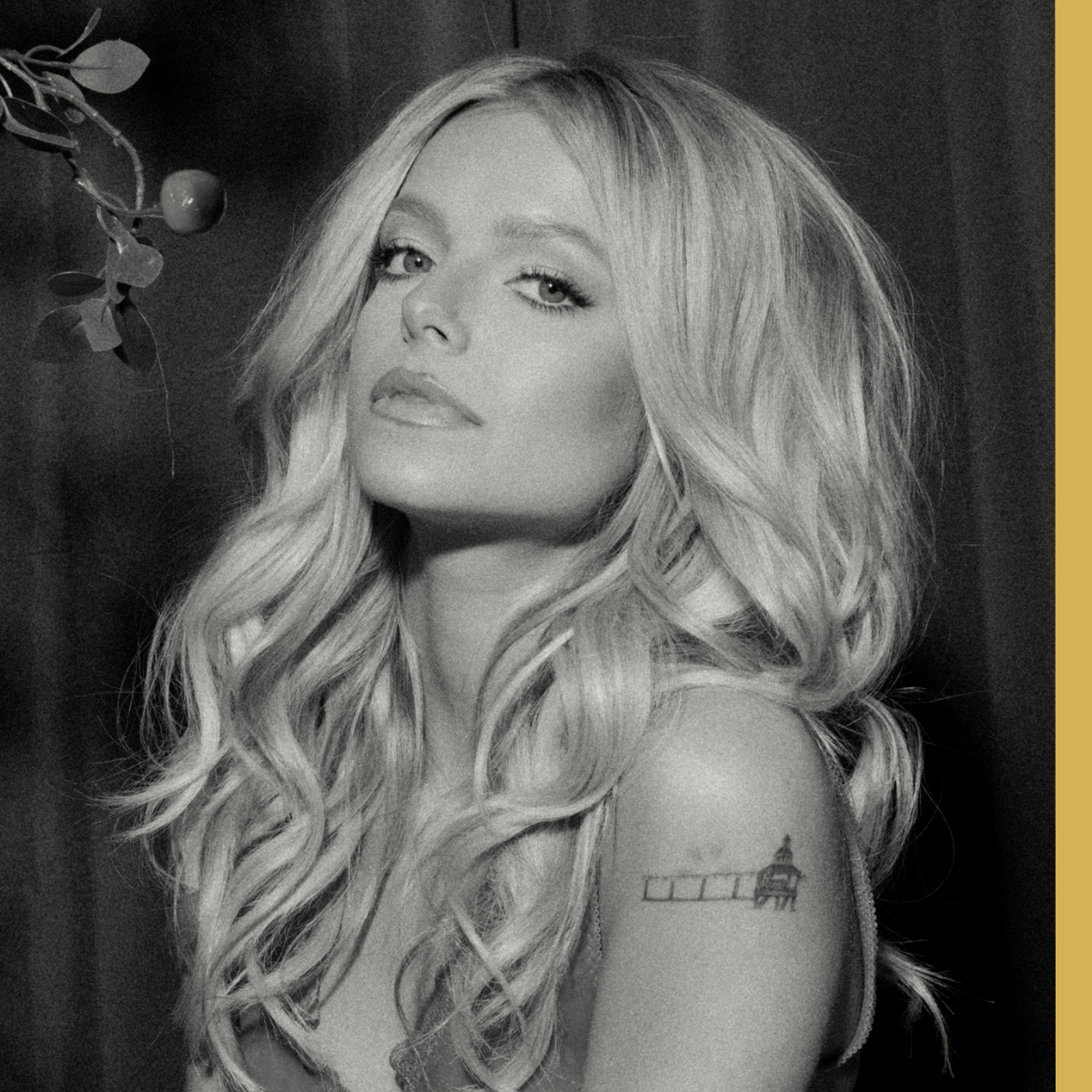

Gena Britt, “What Kind of Memory Will You Be”

Artist: Gena Britt

Hometown: Star, North Carolina

Song: “What Kind of Memory Will You Be”

Album: Streets, Rivers, Dreams & Heartaches

Release Date: November 7, 2025

Label: Mountain Home Music Company

In Their Words: “This song was penned by one of my Sister Sadie bandmates Dani Flowers and co-written by Paul Sikes. She had actually sent it to us several years before she ever joined the band. I remembered it and pulled it back out when I was starting to gather songs for this recording. I asked her if she would mind if I recorded it one weekend that we were on the road and she graciously agreed. We had so much fun working this up and recording it in the studio. It ended up being one of my favorite tunes on the album. And, that Dobro ride at the end of the song by Jeff Partin is out of this world good! I hope everyone enjoys listening as much as we did recording it!” – Gena Britt

Track Credits:

Gena Britt – Banjo, lead vocal

John Meador – Guitar, harmony vocal

Alan Bartram – Acoustic bass, harmony vocal

Jason Carter – Fiddle

Jonathan Dillon – Mandolin

Jeff Partin – Resonator guitar

Tony Creasman – Drums, percussion

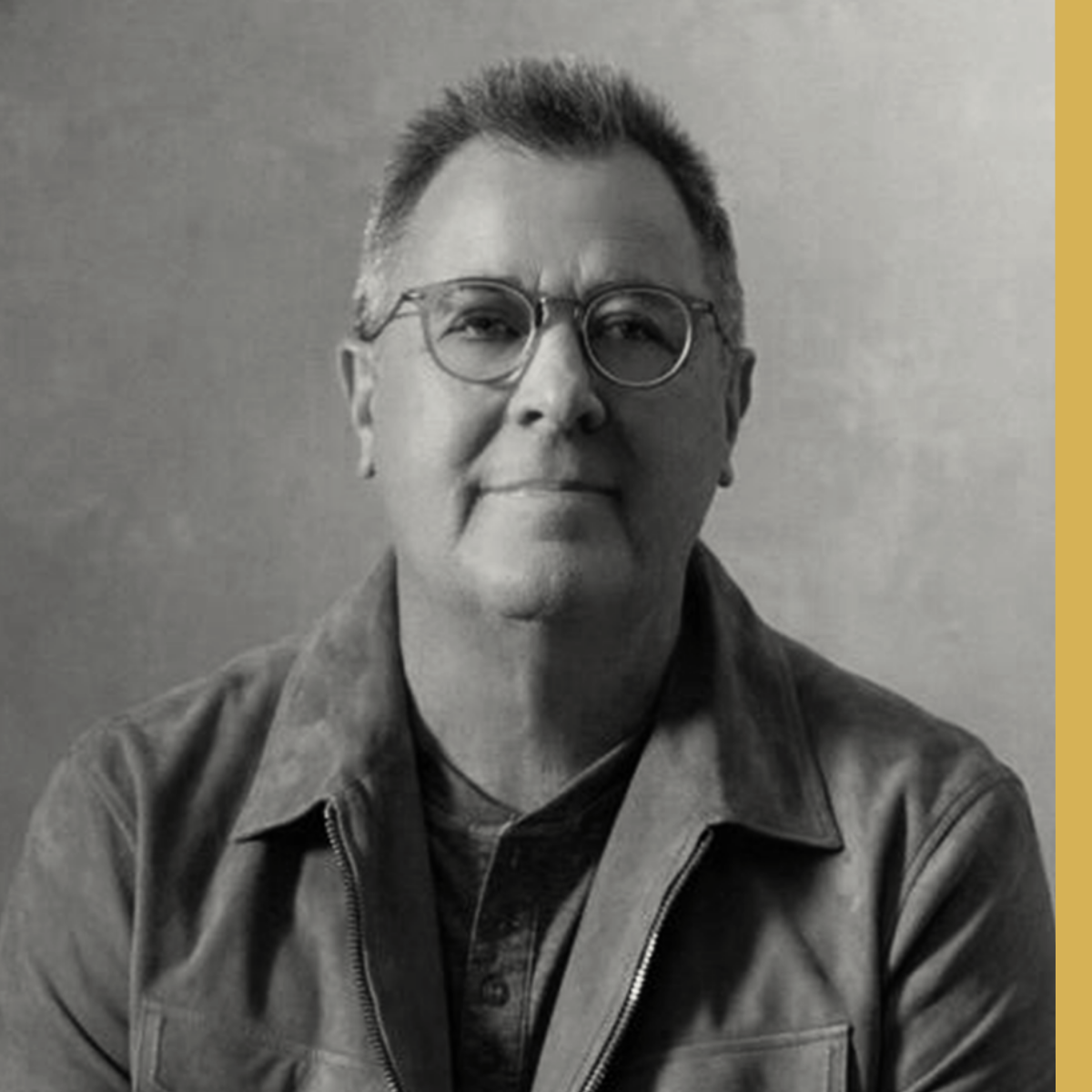

Sammy Brue, “Lonely Mornings”

Artist: Sammy Brue

Hometown: Ogden, Utah

Song: “Lonely Mornings”

Album: The Journals

Release Date: November 12, 2025 (video); January 23, 2026 (album)

Label: Bloodshot Records

In Their Words: “The song ‘Lonely Mornings’ was written in collaboration with Justin Townes Earle’s journals. After I wrote this song, New West Records released a new album of Justin’s called ALL IN which contained unreleased recordings and songs of his. I was ecstatic to find a song called ‘Lonely Mornings;’ it was like a sign. Even though our songs didn’t sound similar, they are connected through a couple lines at the end of his last verse and a similar cadence on the tag line. I found the early rendition of his lyrics and they seemed to be almost a decade old, which goes to show how long Justin really carved a song like it was made of marble. I found inspiration and a whole song in just one verse of his true version of ‘Lonely Mornings’ before I even knew it existed. To me, this song holds the mundane scenes that go with living the artist lifestyle. It also holds a sentiment that we both share, which is the love of spending a morning alone… a writer’s heaven.” – Sammy Brue

The HillBenders, “Tradical Volume 1: I’ve Endured”

Artist: The HillBenders

Hometown: Springfield, Missouri

Song: “Tradical Volume 1: I’ve Endured”

Release Date: August 19, 2025 (single); November 7, 2025 (video)

In Their Words: “We’ve always leaned into ‘bluegrass meets rock ’n’ roll,’ a tag our late manager Louis Myers, co-founder of SXSW, gave us early on. So when we started talking about a new recording project, we didn’t feel the need to change course. Like I tell people, we blame our love for traditional roots music and classic rock on our parents’ vinyl collections. There are so many great legacies to pull from in that wax.

“Instead of putting out a standard album or EP, we decided to start a new series called Tradical, where we let those two loves live together. The first release is ‘Tradical Volume 1: I’ve Endured.’ For the traditional side we went to Appalachian songwriter Ola Belle Reed’s classic ‘I’ve Endured’ and gave it a rock almost disco groove.

“This track also lets you hear our newest bandmates and singer-songwriters, Andrew Morris (banjo/mandolin) and Jody Bilyeu (keys/mandolin). Jody takes the lead vocal on this first Tradical release. This song is our nod to the rocky road that is show business and to the people who keep going against the odds simply because they love music and performing.” – Jimmy Rea

Track Credits:

Jim Rea – Guitar, harmony vocal

Gary Rea – Bass, harmony vocal

Jody Bilyeu – Mandolin, lead vocal

Andrew Morris – Banjo

John Anderson – Drums

Cameron Knowler, “Wilson Rag”

Artist: Cameron Knowler

Hometown: Yuma, Arizona

Song: “Wilson Rag”

Album: East of the Gilas (Lagniappe Session)

Release Date: November 14, 2025 (EP)

Label: Castle Dome Records

In Their Words: “As far as anyone knows, Elizabeth Cotton composed ‘Wilson Rag’ and recorded it a few times on various projects. Though her performances often include a third part which changes slightly from take to take, I decided to focus on the first two parts, adding a bit of reharmonization to make the tune sing with my buddy Will Ellis’ pedal steel playing. Ellis also engineered this track at his home studio in East Nashville, where varied bird songs quietly spilled through a large window. I’m the one playing the ratty Lyon & Healy kick drum from the nineteen teens or twenties, which was performed live with an early-1900s Antonio Grauso acoustic guitar, tuned quite low. I’m also using one of Guy Clark’s old thumbpicks. This tune sure feels great under the fingers and is one that I’ve played for quite some time.” – Cameron Knowler

Track Credits:

Cameron Knowler – Acoustic guitar, kick drum

Will Ellis – Pedal steel, engineer

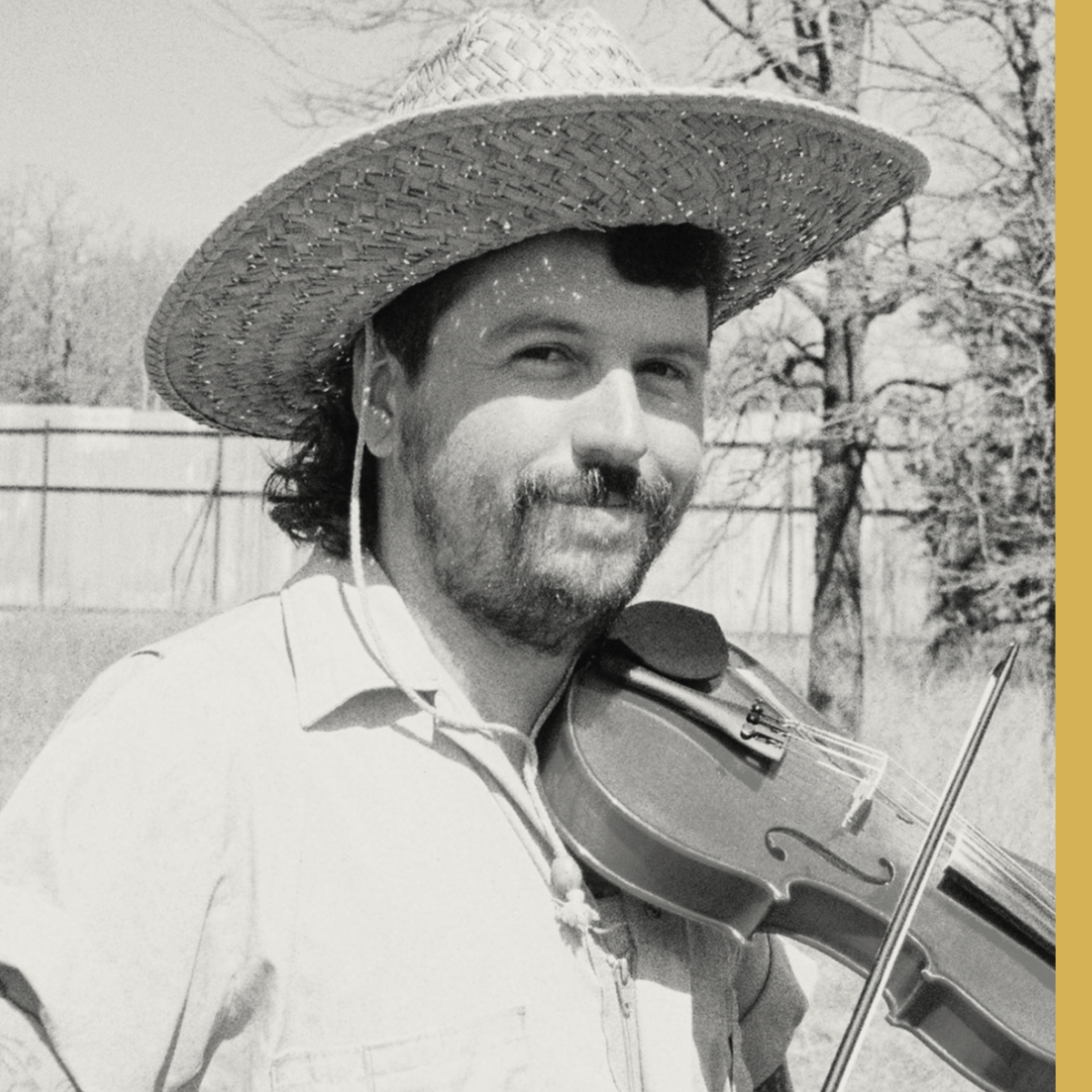

Deanie Richardson & Kimber Ludiker, “No-See-Um Stomp”

Artist: Deanie Richardson & Kimber Ludiker

Song: “No-See-Um Stomp”

Release Date: November 7, 2025

Label: Mountain Home Music Company

In Their Words: “I wrote ‘No-See-Um Stomp’ after meeting a flock of no-see-ums for the first time on the East Coast. As a PNW girl, I was mortified by their existence and the one billion bites I suffered. This tune came out of me very quickly. The first part is the swarm and the second part… human agony. I recorded it once with my band Della Mae and, although there’s an amazing ‘twin guitar’ moment with Avril Smith and Molly Tuttle, I always heard this tune as a twin fiddle tune. As you know, you never encounter just one of these bugs, so I’m very excited to have a twin fiddle version of this with Deanie Richardson. We took a mild ‘controlled chaos’ approach to this, which fits the tune perfectly. Instead of linear twin fiddle parts, we depart here and there, swarming around each other just like the little critters this tune was written for.” – Kimber Ludiker

Track Credits:

Deanie Richardson – Fiddle

Kimber Ludiker – Fiddle

Cody Kilby – Acoustic guitar

Hasee Ciaccio – Upright bass

Tristan Scroggins – Mandolin

Kristin Scott Benson – Banjo

Brendan Walter, “Pipe Dream”

Artist: Brendan Walter

Hometown: Dallas, Texas

Album: Disappearing Days

Song: “Pipe Dream”

Release Date: November 7, 2025

Label: RECORDS/Sony Music Nashville

In Their Words: “I started writing this song while I was still in college, when I was figuring out if I wanted to pursue my majors or follow my lifelong dream of being a musician. At first, music felt like a pipe dream due to the fact that I knew nothing about the industry or how to get started. During college and for about a year after graduating, I bartended full-time to survive while nurturing this dream to make music my full-time gig. Those long nights definitely lit a fire under me to fully pursue music. I had no idea how I was going to accomplish my dreams in this wildly new world, but I knew I wanted it more than anything else and I wasn’t going to stop until I could make it a reality.

“Now, having a couple years in the industry under my belt, I still feel like I’m the new kid on the block, but I know a lot of other artists have felt that way so I thought it was fitting to show a glimpse of my struggles and aspirations along the way. I also worked in a strum pattern inspired by Mumford & Sons, because their music got me into playing guitar and writing songs. I had the opportunity to play with session musicians for the first time when making my debut album and, on this song specifically, I got to play with the very talented Kurt Ozan. Hope everyone enjoys this one!” – Brendan Walter

Photo Credit: Gena Britt by Tom Turk; Sammy Brue by Joshua Black Wilkins.