Artist: Bryan McDowell

Hometown: Baltimore, Maryland

Latest Album: Bryan McDowell (out November 7, 2025)

Personal Nicknames (or rejected band names): Red

What other art forms – literature, film, dance, painting, etc. – inform your music?

Literature, and particularly the novel form, is where I’ve gotten more and more inspiration. I appreciate lessons in a sort of general creative craft that I’ve found by understanding, for example, painters’ processes, but I think since I’ve worked increasingly with lyrics, I’ve turned more to some classic novels for inspo. Some of the newer unreleased songs are from that source, like this laid-back song I have that draws on Crime and Punishment, the first psychological thriller I think it is. The entirety of the book is the suspense and mental anguish of knowing a person who’s committed a terrible crime and is momentarily suspended from actual accountability for it. They’re just tortured to illness by their thoughts. As it turns out, that suspension of accountability is gripping. At least, I think so. What we do in those moments or what we think we would do or think is worth a bit more exploration.

Most songs aren’t quite so directly inspired by another particular work as this, but I know I’ve often taken songs I had that seem unfocused and I’ll back up and try to imagine a central character and maybe even plot out a bit of a storyline, thinking about the main conflict. When I do that, I think I’m always trying to conjure up some feeling of a subtle and human and well-developed character in a book. A novel does this thing of pulling you in close to a character by sustained familiarity and rich development. And a good song might do something similar, it’s just that maybe it’s presented as more of a puzzle box using all kinds of literary devices, meaning-laden language, and rhythm, etc. But if it’s like a puzzle box, then you as the writer still have to be intimate with the characters so that you can unfold them with precision. You have to have everything in its right place.

What’s your favorite memory of being on stage ?

The first year I started touring back in 2012, I was playing with the Claire Lynch Band at MerleFest. I think we had a mainstage afternoon set on Saturday, maybe. Russ Jordan was there and all the usual Wilkesboro crew and there was a decent crowd out in the old Lowe’s lawn chairs. So we finished our set and I walked off and was striking the stage for the next act, which was the Tony Rice Unit. Well at some point I start hearing rumblings that Tony didn’t have a fiddler with him. He had planned on getting king Stu [Stuart Duncan] over for the set, but MerleFest had booked the Nashville Bluegrass Band on like the Creekside Stage opposite Tony’s mainstage set. As it turned out, all the names of great fiddlers being thrown around were over there watching Stu, of course.

Anyway, I was there at the mainstage. Right place, right time. He didn’t know me from Adam, but Tony’s bass player was bending his ear giving me a good recommendation, because he was also the bass player for the Claire Lynch Band. Tony got up there and did the whole line check with the band and walked backstage as if they would play the set as a four-piece, but Mark Schatz must’ve been selling me hard, because five minutes before set time he pulls me back to their little green room and Tony walks up and sticks out his hand and says in his kind of broken-up voice, “How would you like to be a member of the Unit?” He seemed really frail even then and I remember consciously kind of being careful shaking his hand. I got up and did a quick mic check and the tech put a wash of the band in the monitors. Russ announced the Unit and I walked up and played the set with my stomach in my throat and looking fresh off the turnip truck.

I really hope Tony enjoyed it, or at least that he didn’t mind me much over there. He seemed to be having a good time, anyway. It’s the only time I ever got to play with or even speak with him, but his albums were probably the single biggest influence on my musicianship. I was going to Rice Unit concerts before I was born and had played his tapes until the pitch was all messed up and then switched to CDs and played them until they were all scratched to hell – and on and on. Sometime later I found out that Sierra Hull had decided to hire me based on that set with Tony (she was listening out in the VIP section) and then as a result I think I ended up getting a lot of good work with people down the road. I’ve had a lot of good memories on stage now and been able to sit in with many of my heroes, but that one still stands out.

Which elements of nature do you spend the most time with and how do they impact your work?

I got really into section hiking during and before COVID, when I was back in Carolina and I ended up doing some of the Appalachian Trail up in Pennsylvania. At one point I could’ve walked out my front door and a mile up the road was a hundred miles of trails I could link up with that eventually led up to Mount Mitchell, the tallest peak east of the Mississippi. Such a great use of a week or weekend. Woods, mountains, and the quiet are my home. I hear the sweet decomposing forest floor smell is particularly good for mental health.

It doesn’t take long walking like that before everything I should be doing just falls into place. Musically, in life, with people. It all works itself out. I have an important line of a song come to me or a new crooked fiddle tune just falls out. There’s an old-timey tune I haven’t named yet that came to me like that. I think we all have much better versions of ourselves – our more authentic selves – that come back rising up once we get out from under the weight of these daily intrusions.

The sociologist Habermas called it a “colonization of the life world,” crept up slowly over the last 100 years with all the markets reaching their tendrils into our daily lives, encroaching on the time that we have to just be human and experience the world without dealing with being persuaded by something or someone. Going to the woods for me is just a remembering of yourself as a person and who you are in the world, which is the thing I think that modernity would like us most to forget.

What is a genre, album, artist, musician, or song that you adore that would surprise people?

I’m a big fan of Wayne Shorter’s Witch Hunt. I used to listen to that album incessantly back in the day. He’s one of my favorite musicians, generally, but there was some strange and good voodoo happening with the crew on that recording. Everyone was at their most tasteful. That music was greater than the sum of its parts, and the sum of its parts is no small sum if you look at the album personnel. Great writing, great playing.

If you didn’t work in music, what would you do instead?

If I didn’t work in music, I’d own a boutique cheese curds shop that’s word of mouth only and hard to find. I’d call it the Squeakeasy. Just need backers.

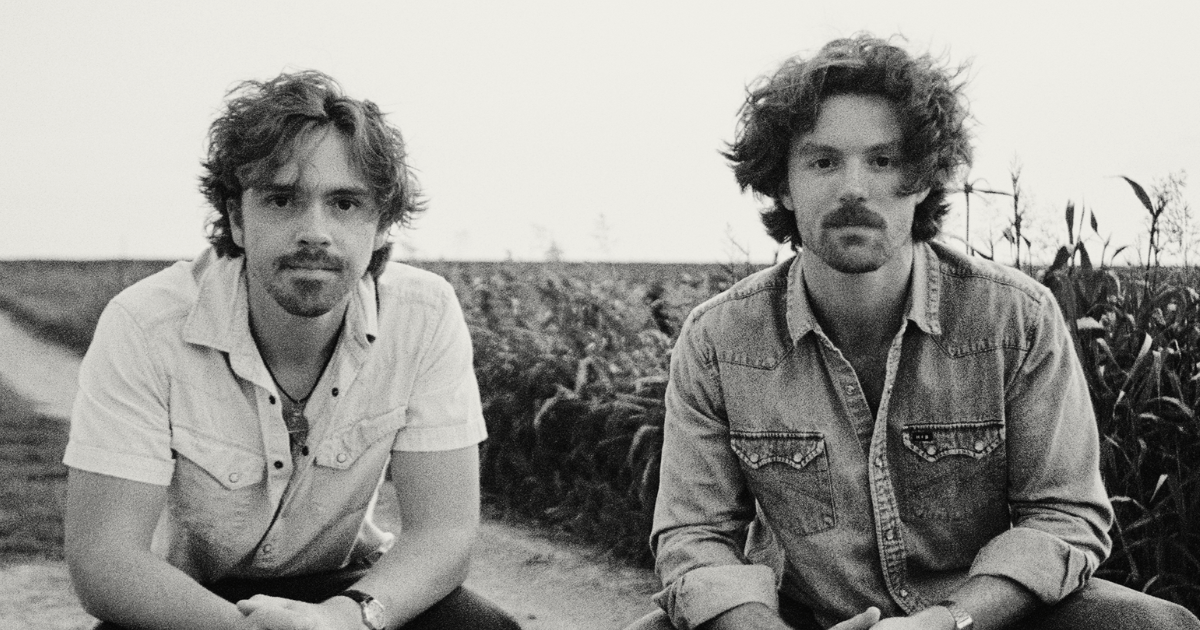

Photo Credit: Margarita Photography