Tag: Alison Krauss

Artist of the Month: Alison Krauss & Union Station

After 14 years, one of the biggest and most well-known bluegrass bands in the history of the music, Alison Krauss & Union Station, have returned with a brand new studio album, Arcadia. Released on March 28 to the delight of bluegrass and AKUS fans the world over, the collection doesn’t merely pick up where the group left off with 2011’s Paper Airplane. Instead, Arcadia soars back through the band’s deep and mighty discography landing somewhere, sonically, between So Long, So Wrong (1997) and Lonely Runs Both Ways (2004) – in other words, this iconic bluegrass band made a bluegrass album.

Alison Krauss & Union Station, by many measures, are one of the most prominent bluegrass bands to ever emerge from the genre. With the smashing success of her late ’90s to 2010s projects with Union Station and the incredible momentum behind their particular blend of bluegrass, “mash,” easy listening, country, and adult contemporary, Krauss catapulted to roots music notoriety, becoming a household name. She’d lend her voice to the blockbuster Coen Brothers film O Brother, Where Art Thou?, tour with Willie Nelson and Family, make two smash hit records with rock and roll legend Robert Plant, back up Shania Twain, duet with artists like Dolly Parton, Andrea Bocelli, Kris Kristofferson, Cyndi Lauper, Ringo Starr, and countless others. Was bluegrass, which Krauss had called her musical home since she was a pre-teen fiddle contest phenom, merely a springboard into fame and notoriety?

Of course not. This is the idiom in which Krauss has made most of her art; this is a second language – or perhaps, a first – and the fluency and virtuosity Krauss and her band have displayed are two of the most important bluegrass exports that registered and resonated with the masses who would become her fans. Krauss’s crystalline and powerful voice, sensitive and deliberate deliveries, endless grit, and one-of-a-kind skill for song curation only bolstered the electric, engaging charm of the bluegrass bones endemic in her artistry. It’s no wonder that this iteration of bluegrass ended up becoming arguably the most mainstream and most recognizable in the U.S., if not the world.

So, Krauss spread her wings and flew, carrying those bluegrass sensibilities – however overt or subtle – into everything she made. Whether the clean and country Windy City or the soulful and rockin’ pair of Raising Sand and Raise The Roof with Robert Plant, or the easy and romantic Forget About It, she had new horizons to run towards. But she always brought bluegrass with her. To arena tours, giant amphitheaters, sheds, pavilions, the biggest festivals, and beyond. By the time Paper Airplane took off, many in bluegrass regarded AKUS as bluegrass’s zenith, its peak, its maximum. Would anyone ever go further, achieve more, or play to larger audiences? This, after all, is the woman and band who up until they were bested by Beyoncé herself boasted more GRAMMY wins than any other artist in the organization’s history. Who could ever top them?

Well, it turns out Alison Krauss & Union Station weren’t just blazing a trail only they could trod down. Arcadia, fourteen years on from their most recent studio release, enters a universe – a resplendent ecosystem, a vibrant economy – that wouldn’t have existed if not for this band creating the factors that would allow it to exist. Folks like Billy Strings, Molly Tuttle, Sierra Ferrell, Tyler Childers, Zach Top, and many more have raised the roof on what’s possible for bluegrass and bluegrass-adjacent artists, what heights they can achieve, and what genre and style infusions are acceptable and marketable.

But AKUS and Arcadia, especially by returning to many of the musical markers from their ’90s and ’00s offerings, reenter the world that they created not as legacy artists or sceptered elders. They seem to be quite happy to consider themselves among these fresh giants in or around or from bluegrass as peers, contemporaries. Legends in their own rights, yes, and with a mythical gravitational pull to all of these acts and musicians they have inspired across generations, but Arcadia doesn’t feel stoic or mothballed, or almighty and shrouded by clouds high atop a sacred mountain. There’s mash that sounds direct from the halls of SPBGMA at the Music City Sheraton, there’s tender, longing romance, there’s rip roarin’ fiddle, there are transatlantic touches, there’s a dash of dystopia, and plenty of that iconoclastic melancholy for which Krauss has become known. There’s also a new voice in the mix, IIIrd Tyme Out’s frontman Russell Moore, who sings lead on four of the album’s ten tracks, filling the “big shoes” of former member Dan Tyminski.

In short, Alison Krauss & Union Station may be roots music royalty, but their status has in no way dulled their dynamism. They could rest on their laurels, but Krauss and her cohort are clearly still staring down fresh, new horizons. Could there be a new wind in their sails, as they embark alongside this new class of arena-ready, large scale bluegrassers? Has a tacit permission been given to return to their essential roots? Or maybe it’s just a matter of time. When bluegrass is in you, in the soil from which you grew, it has a tendency to ooze out all along or all at once. That trail of ‘grassy touches is what got Alison Krauss & Union Station here in the first place, and it’s what will bring them through the next fourteen years, too. Whatever sounds, songs, and stories occur between.

Alison Krauss & Union Station are our April 2025 Artist of the Month. Our 3+ hour Essentials Playlist below covers their entire discography, as well as Krauss’ own releases and other collaborations. Stay tuned for exclusive content coming later this month – like our interview with Alison about the album, powering through dysphonia, how she collects songs, and more. Plus, we have a collection of Six of the Best Alison Krauss Covers and our discography deep dive for beginners and longtime fans alike. Don’t forget about our exclusive Toy Heart podcast interview with Alison hosted by Tom Power or our recent interview with Russell Moore himself about how excited he is for this brand new gig. We’ll be diving back into the BGS Archives for all things AKUS, so follow along on social media as, for a month at least, we’ll be a proud Alison Krauss & Union Situation.

Photo Credit: Randee St. Nicholas

Jason Carter & Michael Cleveland’s New Album is a Fantastic Twin Fiddle Workshop

Following more than 30 years since first meeting and countless times sharing the stage during festivals, the two most accomplished fiddlers in International Bluegrass Music Association history have finally teamed up for their debut album together.

Released March 14 via Fiddle Man Records, the aptly titled Carter & Cleveland sees the combined 18-time IBMA Fiddle Players of the Year Jason Carter and Michael Cleveland flexing their bluegrass muscles on compositions from some of the most prolific songwriters around – like Darrell Scott, John Hartford, Tim O’Brien, and Del McCoury.

Coincidentally, it was with McCoury and his sons’ band, the Travelin’ McCourys, with whom Carter spent the last 33 years playing until the February announcement that he’d be stepping away from the groups to focus on his solo material and collaborative projects, like this one with Cleveland.

“I just thought it was time to start pursuing other things, like my own career,” explains Carter about his decision to leave the bands. “That being said, I never thought I’d be leaving the [Del McCoury] Band. I recently gave a fiddle lesson and the person I was teaching told me he was surprised I left the band and I remember telling him, ‘I’m kind of surprised too.’ [Laughs] But it’s so rewarding to be doing something new with my own band along with getting to play with Mike.

“I’m also really excited to see the McCourys play with their new mandolin player, Christian Ward,” he continues. “There’s no bigger fan of Del or the Travelin’ McCourys than me. This will be the first time since I was 18 years old that I’ll be able to sit out in the audience and watch his show. I can’t wait!”

It was also with McCoury where Cleveland, then 13, first met Carter back in the early ’90s during one of Carter’s (then 19) first gigs with him.

“[The Del McCoury Band] has always had the players that I aspire to be like,” says Cleveland. “I remember going to and recording the band’s shows from the soundboard when Jason was just starting out with them. Then I’d go home and try to play guitar over the recordings to best imitate each part. They quickly became some of my biggest influences in this music, and still are.”

Ahead of the album’s release, BGS spoke with Carter & Cleveland over the phone to discuss the duo’s years-long partnership, the process of bringing this record to life, and their thoughts on the history of duo records in bluegrass music.

You have tunes from Del McCoury, Darrell Scott, John Hartford, Bill Monroe, Buck Owens and other roots music legends on this project, but no originals. What was behind that decision?

Jason Carter: Well, for me, I didn’t have any original tunes at the time we started doing this, so I just started throwing out songs I liked. Then I called some songwriters – Tim O’Brien, Terry Herd, Darrell Scott, and others – and the songs I liked most of what they sent I then played for Mike. I’ve only written one fiddle tune so far, but actually have four or five writing sessions lined up this week, so maybe if there’s a Carter & Cleveland Volume II, I could have a cut on there.

Michael Cleveland: We’ve talked about needing to sit down and write together, it just hasn’t come to fruition yet. When I’ve sat in with Del or Jason in the past we never had time to rehearse, which is similar to how these songs came together. We were able to talk about material and send things back and forth, but we didn’t have much time to sit down and rehearse before recording because we’re both so busy. I hope we get to do that someday, but at the same time songwriting isn’t the main focus for me. I know folks that’ll write a tune every day, but for me that only happens once in a while; when it does I make sure to run with it.

What are some standout songs for y’all on this project?

JC: That’s tough, because I like all the songs on the record. At any given time I could have a different favorite. There’s also some that didn’t make the record we still have in the can and might put out later that could actually be my favorite songs. That being said, I really like the part of “With a Vamp in the Middle” where [Mike] finger picks the fiddle while I’m strumming…

MC: That was your idea!

JC: I heard you play something that sparked that. [Laughs] When you’re in the room as a fiddle player and you hear Michael Cleveland play, it’s all special. He [is] leagues above everyone else.

MC: It’s hardly ever a problem that you have too many good songs, but that was definitely the case when we went in to record. As soon as we put the word out about it we had a bunch of our musical heroes sending us songs to record and they were all great! When I first heard the demo of “Give It Away” from Tim O’Brien I liked the song immediately. Tim was playing old-time banjo on it in the key of D while singing, but once I heard Jason sing it in the key of B I knew it was meant to be a hard-driving bluegrass song.

I also really enjoy “Kern County Breakdown.” The only time I’d ever heard that – which made me want to record it – was from Alison Krauss. She used to play it as a fiddle instrumental and I always wish she recorded it. I don’t know if it’ll happen, but I’m still holding out hope that she’ll put out a fiddle album one day.

She does have her first album in 10 years dropping later this month, so you never know!

Throughout the history of bluegrass music there have been many timeless duo records from the likes of Ralph Stanley & Jimmy Martin to Ricky Skaggs & Tony Rice to Bill Monroe & Doc Watson. What are your thoughts on being the next chapter in that series of collaborations?

JC: I hadn’t really thought of it like that before…

MC: If this album is mentioned in the same breath as any of those, that would be great! We also talk a lot about our favorite twin fiddle albums, which this seems to be more of, and have tossed around the idea of doing this project for 15 years. There’s albums from Kenny Baker and Bobby Hicks, Buddy Spicher and Benny Martin, Buddy and Vassar Clements, and so many more, but there hasn’t been one for a long time now. That’s what originally inspired us to do this. In the last few years people have also finally figured out what a great singer Jason is, which afforded us a lot more room to experiment than if it were a twin fiddle instrumental album.

JC: Mike just has such a good ear. I remember sending him a couple versions of demos I played and sang on and he’d immediately get back to me with suggestions like adding a fiddle lick at the beginning, like on “Outrun The Rain.” He thought it would be great for a high harmony thing two above the lead. As soon as he heard this stuff he had ideas. It was really cool to see how that all came together.

Mike just mentioned the idea for this album has been floating around for 15 years. When did y’all eventually get to work on it?

JC: We started recording a couple years ago. The first session we recorded we actually did at [guitarist] Cody Kilby’s house during COVID, then it was another year or so after that until we got working on it again. Because we didn’t have any rehearsal time, I remember sending voice memos of myself playing fiddle, guitar, and/or singing to Mike to listen to and send suggestions back. I remember being at a show with Del tucked away in the dressing room by myself trying to record versions of these songs or trying to run through an arrangement before sending it to Mike through text message.

MC: I had a great run with the label I was previously involved with, Compass Records, but they weren’t really interested in collaboration albums. With all of my projects and Jason as busy as he is, we were always just in the middle of other things until Jason put out [2022’s Lowdown Hoedown] and I completed [2023’s Lovin’ Of The Game]. It was around that time we decided to take the leap and finally start working on this.

Speaking of taking a leap, I know y’all co-produced this record too. What was your motivation behind that?

MC: We had talked about bringing somebody in. I’ve worked with Jeff White for years on my albums. In a way he helped to produce this one too, which is fitting because I always felt like we co-produced my albums together. For this record there were people we’d send stuff to listen to, even down to the final mixes, just because we respect their opinions, but the final calls were all us.

JC: Even when you’ve got someone like Bryan Sutton in the studio for tracking, he may have an idea he throws out that becomes a big help as well. That could come from anyone involved in the session, even engineer Sean Sullivan, who we leaned on heavily as well because they do this every day. These people are here for a good reason, because they’re super talented and play some of our favorite music. And when it comes to Cleve, I’m all ears. He always has good advice.

MC: When you first start recording, you don’t always know what sounds good. It’s like with playing, singing, or anything else, the more you put yourself in those situations the more you understand what you want to hear and how to achieve it. Working with Jeff in the past, we’d be together during the day when all of the sudden he’d say, “Hey Mike, I gotta take off for a few hours, produce for a while.” It freaked me out the first time he did that, but it forced me to get comfortable in the situation and forced me to trust my ear more. Jeff having that faith in me also gave me a little more confidence in myself that I was making the correct decisions and to continue trusting my instincts.

JC: With the Travelin’ McCourys, all of those records were produced by the band along with most of the stuff we did with Del, too. I did produce my solo record, Lowdown Hoedown, though. But even on that, when we were recording Sam [Bush] and Jerry Douglas were there. I remember Jerry – who produced a lot of the McCourys’ stuff early on – always had great ideas on arrangements and different things to put in when he spoke up, which was a huge help. Getting to be in the studio with him is an education you can’t get anywhere else.

Jason, you briefly spoke of a few of the album’s players there. But they’re far from the only top-notch pickers you have on this record, with the likes of Vince Gill, Charlie Worsham, and Sierra Hull, among others. How’d y’all go about deciding who to bring into the fold?

JC: We just tried to think of who would best fit with the songs as we listened to demos for each.

MC: It also came down to who was available at certain times. Guys like Bryan Sutton, Cory Walker, and Alan Bartram played on most of it. I remember days where Sam Bush was available on mandolin and others where Harry Clark filled in. Some of the first sessions we did after the pandemic were with Cody Kilby and Casey Campbell followed by David Grier and Dominick [Leslie].

And going back to something Jason said earlier, I also leaned on Bryan a lot, specifically about what songs he thought it would be good to have Sam on, which led to his inclusion on “Middle of Middle Tennessee” and a few others.

What has music, specifically the process of bringing this record to life, taught you about yourselves?

MC: This was one of the first things I’ve done without a producer being there. Most of the time we would agree on decisions, but other times you don’t know what the right thing is and somebody has to make the call, because that’s typically something a producer would do. When it’s just you there’s no question, but when you’re working with somebody you want to make sure it’s a collaboration and not one person running the ship. Recording this album has taught me to be more aware of that.

JC: The singing part of this too, that’s still pretty new to me. I’ve sung on other people’s records, my solo album and with the Travelin’ McCourys, but being the lead singer throughout is a new venture for me and something I really enjoyed getting to do with Michael.

What do the two of you appreciate most about one another as both musicians and people?

JC: Everything about Mike’s playing, he’s just on another planet right now, and as a person he’s the same way. I recently got married and Mike was my best man, because no matter what he does he is the best man!

MC: Hearing Jason play with Del, he’s always been the fiddler I’ve wanted to be. We’re both into the same stuff, which is why I think we work together so well. It’s why we’re able to jump on stage and play twin fiddles without rehearsing, which is usually a mess when you do that. Getting to work with him on this album has been a dream come true for me.

Photo Credit: Lead image by Sam Wiseman. Square image by Emma McCoury.

Basic Folk: Sierra Hull

(Editor’s Note: The entire BGS team would like to congratulate Basic Folk on 300 amazing episodes of the podcast! Celebrate #300, featuring GRAMMY nominee Sierra Hull as our guest, with us below.)

When mandolinist Sierra Hull was little, her dad told her she was really good “for a 10-year-old.” The older Hull knew Sierra had a fiery passion for the instrument and he knew exactly how to motivate his daughter. He went on to say that if she wanted to go to jams and porch-play for the rest of her life, she’d learned enough. He gave her realistic advice, saying if she wanted to dedicate her life to music, she would have to work really hard. Because “that 10-year-old cute thing is gonna wear off.” Sierra, who would draw pictures of herself playing at the Grand Ole Opry with Alison Krauss and doodle album covers with the Rounder Records logo, took his advice to heart and got to work.

LISTEN: APPLE • SPOTIFY • AMAZON • MP3

Since then, Hull has shared the stage with more heroes than one could count. She’s inspired a new generation of younger players, she’s released five albums, and she’s considered a master of the mandolin. Her new album, A Tip Toe High Wire, is set for release March 7. In our Basic Folk conversation Sierra reflects on how growing up in the small town of Byrdstown, Tennessee, shaped her musical identity alongside bluegrass, gospel, and family traditions. She shares memories of family gatherings filled with music featuring Aunt Betty and Uncle Junior, the profound influence of church hymns, and how these experiences continue to resonate in her playing and songwriting.

Sierra also discusses the significance of A Tip Toe High Wire, her first independent release, highlighting the freedom and growth that come with that independence. She emphasizes the importance of authenticity in her music, allowing herself to explore new sounds while remaining grounded in her bluegrass roots. Elsewhere in the episode, she opens up about her personal growth, the pressures of being labeled a child prodigy, and her journey toward embracing imperfection in her art. We also dive into what we’ll call her “Stevie Nicks Era” with the amazing cover art on the new record. Sierra enjoys playing with elaborate styles in her album artwork and red carpet looks (helloooo CMA Awards). With a candid perspective on the challenges of the music industry, she encourages listeners to find joy in the process while appreciating the beauty of vulnerability.

Photo Credit: Bethany Brook Showalter & Spencer Showalter

“Not Easy Shoes to Fill” – Russell Moore Gets the Gig of a Lifetime: Alison Krauss & Union Station

Russell Moore has been a professional musician and bandleader for 40 years and, though he wouldn’t describe himself as complacent, he does readily admit he generally knows what he can expect from that job.

“It’s almost like, ‘Okay, I know what this week is going to bring and what next week is going to bring,’” he shares over the phone. “It’s the same thing, even though you try to explore different opportunities … I never would have thought that at this point in my career that this opportunity would arise.”

Back in early December 2024, Alison Krauss & Union Station announced their first headline tour in nearly ten years and, with that announcement, that Moore himself would be joining the band. The bluegrass community responded with an outpouring of love for Moore, his talent, and his iconic, long-running bluegrass band IIIrd Tyme Out while marveling at how perfectly he and his voice would fit into one of the most prominent, best-loved, and best-selling string bands in music history.

Once fears of IIIrd Tyme Out being benched were totally allayed – the band has lasted 34 years so far and has no plans to curtail their efforts with Moore’s new gig – the ‘grass community set their sights on the next announcement from AKUS, which came in January: Arcadia, their first album since 2011’s Paper Airplane, will release March 28.

Arcadia will be the starting pistol for a breakneck six-month tour that will find Alison Krauss & Union Station (and their newest member, Moore) criss-crossing the continent to perform at some of the most notable venues and festivals in the scene. Many of which Moore will find himself checking off his bucket list for the very first time.

To mark the occasion, and as we anxiously count down the weeks to Arcadia and the Arcadia Tour, we sat down with Russell Moore to chat about his career, his plans for IIIrd Tyme Out, and how energized and excited he is by this once-in-a-lifetime chance. As he puts it, he has very big shoes to fill – but perhaps he is the only one concerned about having the chops to fill them.

You’ve been leading your own band for so long and you’ve been the person to “make the call” – hiring a sideman, or hiring someone to fill in, or finding a new band member. So how does it feel at this stage in your career to get this kind of call to join a band like Allison Krauss & Union Station? How does it feel to be on the receiving end for a change?

Russell Moore: What a blessing. It’s definitely the other side of the fence! For 34 years I’ve been running IIIrd Tyme Out and making the decisions or helping make the decisions. That’s a job in itself. You wear many different hats when you’re doing that.

The last time that I was in a situation like I’m going into with AKUS was back when I was with Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver. That was basically, “I’m the guy that plays guitar and I sing” and everything else was pretty much taken care of. Since then, up ‘til now with IIIrd Tyme Out, I’ve been heavily involved with all the decisions and making things happen, which like I said, it requires several different hats to wear day-in and day-out.

This is going back to that time, before IIIrd Tyme Out. And I’m excited about it. It really gives me the opportunity to focus totally on the music and my part in the band, rather than anything else that goes along with running a band. That’s exciting in itself. I will say, it’s going to take some getting used to, because I know that I’m going to be saying, “Oh, what can I do today to help this thing out?” That’s going to be a change of pace for me!

But I’m looking forward to it. Honestly, I’m looking forward to not having to worry about anything else other than my position in AKUS and just doing my job to the best of my ability and that’s it. That’s gonna be pretty cool. I guess you would say a little weight off of my shoulders.

You can set down the CEO hat and pick up the “being an instrumentalist and a vocalist and a technician” hat. Of course it’s got to feel exciting in some ways to get to step back into that role of being an equal part collaborator in a band instead of having to wear so many hats and having to be a lightning rod for everything.

RM: It is. It definitely is. I did experience just a little bit of this a few years ago. Jerry Douglas called and asked if I could go out for a few days with the Earls of Leicester, which I did and it was the same thing. I played mandolin and I sang my harmony parts with Shawn [Camp]. And I didn’t have to do anything else. That was all I had to do. For a few days there, I got to relieve myself of all the responsibilities of running a touring band on the road, and it was cool. I enjoyed it. I really did.

I’m not going to lie, I’m not saying that I don’t enjoy running a band, I’m not saying that whatsoever! But it was nice to step back for a few days and just be that. So I see this, for the six months between April and September, being sort of in the same picture. I wanna focus everything I can, all the time I’ve got, on playing the music, being in the position that I’m in, and doing the best I can. Just focusing on that. That’s going to be cool. I’m not going to have to worry about, “Did the bus get there on time? Is there something wrong with the bus?”

I know I’m not the only one who was super excited to hear this news and also thought immediately, “I never would have connected these dots myself, but who else has a better voice for that gig?” You think of Dan Tyminski, of Adam Steffey, the guys who have been singing vocals in this band, they have that sort of warm, honeyed, Mac Wiseman-like bluegrass voice – less of the high lonesome and piercing, even though you have the range and you can get up there, too.

So many people’s reaction to the announcement was that you have a voice that’s perfect for this gig and for what we all come to expect as the AKUS sound. Did you have that realization too? Did you think, “Oh yeah, this is perfect for my voice”? Or did you feel like, “I’m going to have to work at this.”

What was your general reaction, musically, to coming into this? Not just as a guitarist, but also as a vocalist – and then, I assume you’ll be playing some mandolin too, like you said you were doing with Earls of Leicester. So how are you approaching it musically?

RM: I will be playing a little bit of mandolin, not a whole lot, but my main gig I guess you’d say would be playing guitar and vocals – harmony vocals and some lead vocals as well. I’ll be honest with you, Justin, I was concerned about some of the harmony singing. That’s the biggest thing.

It’s really intricate.

RM: It is very intricate! It’s not in the same breath that I usually sing at. I tend to sing very full throated. For lack of a better term, it’s a male voice trying to sing very high. I do it in a robust way. I do have subtleties that I use as well, but this application of trying to blend with Alison’s voice is a different place to be, for me, for sure.

I do sing harmony and I have for years, here and there, but still my vocal technique has always been full throated and far more harsh, a male vocalist trying to sing very high. This is a different application. I tried to do that on all the songs that I’m going to be singing harmony on with Alison, it would be too abrasive. I’m learning how to make it work with my voice and her voice. That is a really nice combination, [you don’t want] me standing out because of my approach to the harmony.

Of course, I do have songs that I’ll be singing lead on. Those, I’m just back to my old self doing my thing. But when it comes to the harmony stuff, most of the time I’m having to really listen and focus on how to project my voice to make her sound as best as she can and not interfere.

Are you going to be singing lead on some of your own music with AKUS?

RM: No. There might be one song, and I’m not going to give away any of the stuff that she has planned for the set list, but there might be one song that people recognize from IIIrd Tyme Out during the performance. For the most part, this is Union Station. We’re not trying to bring in Russell Moore and IIIrd Tyme Out into the project whatsoever. We’re still around, we’re going to be performing when I’m not on the road with AKUS. There might be a small ode to IIIrd Tyme Out during the show, but it will be very small.

I’m not here to promote IIIrd Tyme Out with Alison Krauss. I’m here to promote Alison Krauss & Union Station and to be a part of that group and promote what this record release is and the stage show. I am a team player and I told them all, “You’ll never find anybody that’s more of a team player than I am, because I understand what that means.”

You’ve seen it on both sides. I’m glad you mentioned IIIrd Tyme Out continuing, because I think a lot of people’s natural reaction to the news was, “What about IIIrd Tyme Out!?” Of course IIIrd Tyme Out’s been going for so long, they’re gonna keep going.

RM: IIIrd Tyme Out is here to stay. When the conversations started about my being a part of Union Station going forward, I had a lot of questions. Can I do this? Should I do this? And that was one of them: “Will my band support me in this decision, or if I say yes, will they support me?”

[I consulted] my family, my wife, and everybody around me – it wasn’t a decision that was made quickly. I had to talk to people. Once I talked to my band members and I got their total support and thumbs-up affirmation – along with my wife, family, and friends – it was just like, “Okay, I have no reason not to do this. Everybody says I should and it’s a great opportunity.” At that point, I said yes.

Hopefully I can fulfill the position, because it’s not easy shoes to fill. I can tell you that right now I’m a huge Dan Tyminski fan. I have been since he came onto the scene way back – we’re talking Lonesome River Band days. He is so unique and his position with Union Station, until recently with his own band, that was the epitome of his career in my opinion.

Then, of course, he gets the head nod for Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? And the Stanley Brothers song, “Man of Constant Sorrow,” it’s still incorporated into his shows. I love the Stanley Brothers’ [version of the] song. I really do. But when I think about that song, I think about Dan Tyminski.

I guess the point is I’m a huge fan of Dan and his work. He is such an intricate part of what Union Station has been up to now. I think that those are big shoes to fill. I just hope I can facilitate that to everybody’s liking. I know there’s going to be some people that say, “No, it’s not Dan, it’s just not the same.” But I do want to say there are [many] eras of Union Station that were awesome, as well. You go back to when other people were in the group. Adam Steffey–

I’m partial to the Alison Brown era, too.

RM: Alison Brown! Oh, gosh, yes. Tim Stafford along that same time. I can’t say there’s been a bad ensemble for AKUS. It’s just evolved. And the fact that Dan was there for so long, that kind of solidifies that is the sound that most people – especially younger people who didn’t really start listening to AKUS until let’s say 20 years ago – are hearing. What they’re hearing is Dan Tyminski on guitar, singing harmony, and singing lead. That’s what they’re used to. That’s what they realize is AKUS music, and here’s this Texas guy coming in here trying to fill those shoes. I just hope I can satisfy everybody. I’ll do the best I can.

It’s gotta feel exciting, especially after having done something like this your whole entire life, to have that sort of childlike wonder at it feeling so brand new and so fresh. Even after you have done literally exactly this for so long, there are still things that you’re excited to accomplish and new territory you’re excited to explore. That sounds really energizing and really positive.

RM: It is energizing. I’ll be honest, Justin, I’ve been playing music full time for a good 40 years. That’s awesome. And at this point, after 34 years of IIIrd Tyme Out – I’m not going to say I’ve become complacent, but it’s almost like, “Okay, I know what this week is going to bring and what next week is going to bring.” It’s the same thing, even though you try to explore different opportunities and things that come within that.

But this, I never would have thought that at this point in my career that this opportunity would arise and I’d get to do something like this. Because, like I said, I’m not so much complacent, but I know what’s ahead. When the phone call was made and we talked, I had no idea that I had another option, another fork in the road. This is absolutely surreal, in a lot of ways, for me to get this opportunity and without giving up IIIrd Tyme Out. All the support from everybody that I know, like I said, there was no reason to say no.

Another part of this that I’m really excited about [is being] able to experience some of these places, these venues, these shows that I’ve never been to before. Just being able to experience it – like playing Red Rocks Amphitheatre – and just so many places that I’ve always wanted to go to and perform at. I’m going to get to do that!

Checking them off the bucket list.

RM: There you go. It wouldn’t be possible, I don’t believe, with IIIrd Tyme Out. I was always exploring new opportunities and things like that, but I don’t think it would have been possible to perform at some of these places without being a part of AKUS.

To me, “Looks Like the End of the Road,” the first single from the upcoming album, feels like classic AKUS. The So Long, So Wrong era is what it reminded me of first. You still have those tinges of adult contemporary, you have the pads and the synth-y sound bed underneath it, and it almost feels transatlantic a bit here and there. Overall, it sounds like classic, iconic Allison Krauss & Union Station. What are your thoughts or feelings on the single or what can you tell us about that first track?

RM: I think that the song is a great representation of what is coming out with the full album release, Arcadia. It is a great nod to Alison Krauss & Union Station music over the last several years and the last several recordings.

I think that the song itself is just well written and perfect for Alison to sing. There’s a small part of harmony vocals – and what I love about the way she constructs her arrangements is that it’s not overdone with harmonies. This is Alison Krauss & Union Station, it’s not just Union Station. So the focus is on Alison and her vocals. In my opinion, that’s the way it should be. This song doesn’t come out from the get go with a five-string banjo just blasting off. It’s a great construction of the arrangement and the vocals.I think it was perfect.

The only thing that people have said is that the title itself made them think that this was the end of Allison Krauss & Union Station! Which is so far detached from the truth. It was just the first single that was released. It’s a beautifully constructed song.

I will say, this song is just a piece of the puzzle to the rest of the recording. It just paints a beautiful picture and a wonderful listening experience. When people get to hear the full album, they’ll understand what I’m talking about. It’s just awesome. It’s just, it’s a piece of the puzzle.

You’re going to be blown away. Absolutely blown away, as I was. I had my headphones on. I can’t tell you how many nights before I’d go to sleep, I’d have my headphones on [listening]. I listened to it two, three times a night, just because it was so enjoyable. It was just that good. I know that everybody else is gonna feel the same way when they hear the whole project.

Photo Credit: Matt Morrison

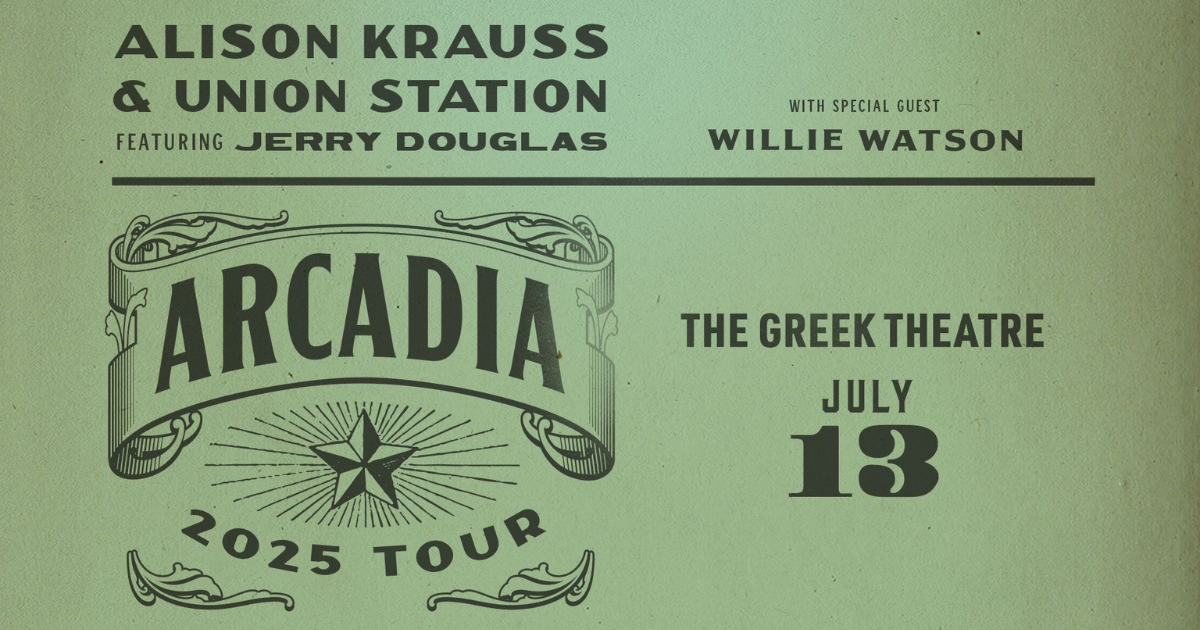

Alison Krauss & Union Station Announce ‘Arcadia,’ Their First Album in 14 Years

A few short weeks ago, Alison Krauss & Union Station made roots music waves announcing their first headlining tour since 2015, featuring dozens of dates stretching from April ’til September of this year. Now, the 14-time GRAMMY-winning bluegrass band is announcing their first album in 14 years, Arcadia, set for release on March 28 on Down The Road Records. This marks the return of Krauss & Union Station to collaborating with Rounder Records founders Ken Irwin, Marian Leighton Levy, Bill Nowlin, and John Virant, who recently began Down The Road Records. Decades ago, Irwin first signed the fiddle phenom when she was still a teenager.

With the album’s announcement, the band have released Arcadia‘s first single, “Looks Like the End of the Road,” a song written by Jeremy Lister that hearkens back to the emotive slow burns of classic AKUS albums like 1997’s So Long, So Wrong. (Listen above.) Gritty Dobro, by none other than Jerry Douglas of course, and pining mandolin tremolos are underpinned by sweeping pads and transatlantic textures. It all at once sounds like idiomatic Union Station while clearly signaling their transition from a former era to a newly minted one. “Looks Like the End of the Road” is an apropos beginning for this world-renowned group starting down a new highway.

“Usually, I find something that’s a first song, and then things fall into place,” says Krauss via press release. “That song was ‘Looks Like the End of the Road.’ Jeremy Lister wrote it, and it just felt so alive – and as always, I could hear the guys already playing it.”

“The guys,” at this juncture, include longtime band members Douglas, Ron Block, Barry Bales, and a new addition, Russell Moore, a 6-time winner of the IBMA Male Vocalist of the Year Award and a veteran frontman of bluegrass mainstays IIIrd Tyme Out.

“To say I’m excited about recording and touring with Alison Krauss & Union Station would be a huge understatement,” Moore gushed in the band’s December 2024 tour announcement. “After 40 years of playing music full-time and leading my own group for 34 years, this opportunity is among the few things at the top of the list that my music career has offered me. My hopes and desires are to fill this spot in AKUS with the same professionalism, precision, and thoughtfulness as other members who have held this position before me, and I’m looking forward to the ‘ride!'”

Tickets for the gargantuan Arcadia tour – which will feature special guest Willie Watson – are already on sale. Anticipation for the first studio album in 14 years from one of the most prominent and impactful bluegrass groups in history is remarkably high. Yet again, with Arcadia, Alison Krauss & Union Station are poised to bring their singular blend of bluegrass, Americana, adult contemporary, and stellar song interpretations to millions of fans and listeners around the world.

Want more? Listen to our exclusive Toy Heart interview with Alison Krauss here.

Photo Credit: Randee St. Nicholas

BGS 5+5: Olivia Wolf

(Welcome to another 5+5! Hit play, scroll, and get to know artists, creators, and roots musicians of all sorts with five questions and five songs.)

Artist: Olivia Wolf

Hometown: Leipers Fork, Tennessee

Latest Album: Silver Rounds

Which artist has influenced you the most – and how?

Gillian Welch. She has shown me that lyrics can be both beautiful and dark, honest and true. Her instrumentation is brilliantly simple and to see her play live is to transcend to a different plane.

What’s your favorite memory from being on stage?

We played “The Wild” in Seattle, and I asked if anybody had gone fishing that day. A fella had been out that morning and caught three coho salmon. When the song started he closed his eyes and I knew he was back on the ocean in the breeze and the water. I love to see other people getting to escape through my music.

What other art forms – literature, film, dance, painting, etc. – inform your music?

Photography, antiquing and home décor design, cooking, and hosting friends.

What is a genre, album, artist, musician, or song that you adore that would surprise people?

I love Daft Punk. Especially their song “Something About Us.” They influenced a lot of the cosmic aspect of my album and I greatly admire their lyrics and musicality.

If you didn’t work in music, what would you do instead?

There is nothing I could do instead, I am married to the music.

Photo Credit: Alysse Gafkjen

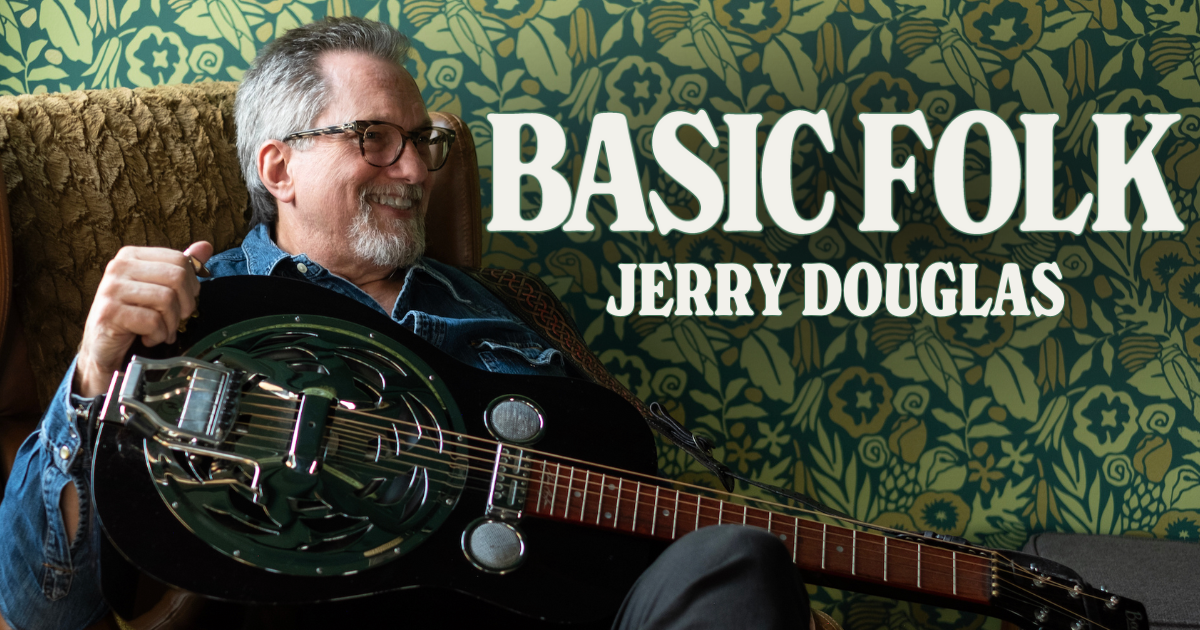

Basic Folk: Jerry Douglas

Jerry Douglas is widely regarded as the best Dobro player in the world. Alison Krauss, Emmylou Harris, and James Taylor are counted among his many collaborators and his four-decade career has earned him 16 GRAMMY Awards and numerous other accolades. In our Basic Folk conversation, he shares stories about his upbringing in Warren, Ohio, where his father’s steel mill job and love for music instilled in him a strong work ethic and a passion for playing. He also talks about getting scouted as a teenager by The Country Gentlemen, one of the greatest bluegrass bands ever, who eventually took young Jerry on tour.

LISTEN: APPLE • SPOTIFY • AMAZON • MP3

In addition, we discuss Douglas’ latest album, The Set, which showcases his mastery of the resophonic guitar and features a unique blend of bluegrass, country, and Americana sounds. He also opens up about his experiences working with Molly Tuttle, John Hiatt, and other notable musicians, highlighting the importance of collaboration and creative freedom. Our chat offers a glimpse into Jerry Douglas’ life, influences, and artistic approach through his humility, humor, and dedication to his craft.

Photo Credit: Scott Simontacchi

Jerry Douglas’ New Album, ‘The Set,’ Tracks His Musical Evolution

Undefinable by a single era, genre, or instrument, Jerry Douglas’ otherworldly picking prowess on Dobro and lap steel guitar knows no bounds. Whether it’s running through Flatt & Scruggs songs with the Earls of Leicester, kicking up covers like The Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” or conjuring up jazz-like improv jams, the sixteen-time GRAMMY winning musician has a way of drawing the listener in with his tasteful tunes.

That trend continues on The Set, his first studio album since 2017 – although he did stay busy producing records for Molly Tuttle, Steep Canyon Rangers, John Hiatt, Cris Jacobs, and others during the time in between. Released on September 20, the record captures the sound of Douglas’ live set with his current band – Daniel Kimbro (bass), Christian Sedelmyer (violin), and multi-instrumentalist Mike Seal – with a mix of new and original compositions, reworkings of older songs from his catalog, a couple of intriguing covers, and even a concerto.

BGS caught up with Douglas ahead of his tour dates in support of the new record – and his induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame this week – to discuss the motivation behind The Set, the similarities between Molly Tuttle and Alison Krauss, and much more.

This is your first album in over seven years. What was your motivation for returning to the studio after such a large gap?

Jerry Douglas: I’ve been doing records for everyone else those past seven years. [Laughs] We’d go out and play a show and people would come up afterward and ask where they could find this song or that song. It got me thinking, since the songs I play live are scattered across many different records — some of which are out of print — that it’d be a good idea to get them all into one place, one album. It’s not a compilation record by any means, it’s just how I love to hear these songs now.

Speaking of how you love to hear these songs now, you’ve recorded many of them in the past. This includes “From Ankara To Izmir,” which you first recorded on lap steel before opting for the Dobro this time. What led to that shift?

When you first write a song you don’t know it, because you haven’t lived with it yet. You need to play it about 100 times and really flesh it out to see what all’s in there. When I originally recorded “From Ankara To Izmir” in 1987 for the MCA Master Series we had a much bigger, bolder band around it. However, the more I got to playing it out live the better the Dobro felt on it. It allows me to be more dynamic with the song, which I also cut with drums in 1993 before switching things up and leaving them out this time.

We actually haven’t used drums since the record I made with John Hiatt in 2021. He didn’t want them, so we used the rest of my band… it felt great having all that space the drums usually filled back, so we just continued as a four-piece after that. It’s gone on to inform a lot of the music on this record, not just with that one song.

I love the evolution that songs can take over time, whether it’s something as simple as changing out one instrument like you’ve done a couple times here or going from a full band to something that’s solo acoustic. Different arrangements breathe completely different life into a song, and your record is a great example of that.

Even Miles Davis recorded a lot of his songs two or three times with different bands. He wanted to hear them with the band he was with at that moment, which all included different people, personalities, characteristics, and playing styles. Music is meant to evolve over time as influences and circumstances change. Songs are traveling through their life collecting little pieces to add to themselves just like the rest of us do.

That room to experiment is only expanded with your band, who you’ve been with now for eight years. How did the chemistry you have with them help to drive the sonic exploration behind The Set?

Like you said, we’ve been together for a long time now. We’ve been everywhere together and have become good at picking up nonverbal cues from one another. A lot of times I’ll just give Daniel a look and he knows what to do. That trust allows us the freedom to experiment and keep things fresh for ourselves, which in turn keeps it fresh for the audience as well, whom we don’t ever want to leave behind.

That same attention to detail can be felt in the album artwork as well, which I understand comes from a connection you made across the pond while there for the Transatlantic Sessions?

Yes. William Matthews is a famous western watercolor artist who was in Scotland with me when we started rehearsing for the Transatlantic Sessions right after COVID. We typically tour the country at the end of January and into February for 10 days playing the entire show and William was following us around painting. One day I walked into his hotel room and his paintings were all the way around the wall. One of them was of Doune Castle – seen in both Monty Python & The Holy Grail and Game Of Thrones – that, unbeknownst to us at the time, ended up becoming The Set’s cover art.

Earlier we touched on all the producing work you’ve been up to lately. One of those has been Molly Tuttle, who you’ve worked with on her past two GRAMMY-winning albums. Given your close ties to another trailblazing woman of bluegrass, Alison Krauss, do you notice any similarities between the two and the approach they have to their craft?

They’re both amazing singers. I learned a long time ago that when Alison tells me she can do better, she does, and Molly’s the same. Both have a way of exceeding my expectations on a take when I thought they couldn’t do better than the one just before it, but every time the new one turns out head and shoulders above the one that I had been satisfied with. It’s taught me to always trust the artist no matter who it is I’m working with.

In that same sense, I think about Earls of Leicester as Flatt & Scruggs – what if they’d said “wait a minute” and gone back in [to the studio] to change one little thing? When you’re recording, everything happens so fast that you can come back to it and go in a completely different direction. That’s what I love so much about my new record, even some of the mistakes that I made on it aren’t really mistakes, they’re just different directions.

What has music taught you about yourself?

I’m an introvert who can speak in front of thousands of people and have a good time at a party, but when I’m alone I’m really alone, but in a positive way. It’s like having two lives, but I’m not acting in either one of them. What a privilege it is to be true to yourself and have a full life at the same time. I get to go out and play music, then come home and fix the faucet.

Lead Image: Madison Thorn; Alternate Image: Scott Simontacchi.

First & Latest: 34 Years Later, Alison Brown Still Finds ‘Simple Pleasures’ on Banjo

In 1990, when banjo player Alison Brown released her debut album, Simple Pleasures, she had no idea where her career could or would lead. GRAMMY nominations, IBMA Awards, touring and performing with Alison Krauss, Michelle Shocked, the Indigo Girls, Steve Martin, and many more, founding a record label that would become a keystone in roots music – none of these impressive accomplishments were on her horizons, literal or hypothetical. Brown just wanted to play the banjo.

She had recently left her job in investment banking and wanted to give her musical career a legitimate go of it. Tasking herself with intentionally writing an album’s worth of original tunes, over the years from 1988 to the project’s release on Vanguard Records in ‘90, Brown pushed herself sonically, aesthetically, and compositionally. The result was demonstrably spectacular and effortlessly cutting-edge.

Simple Pleasures, which was produced by David “Dawg” Grisman and included Alison Krauss, Mike Marshall, Joe Craven, and more among its cast of collaborators, would help launch Brown’s now decades-long career as a bluegrass and roots music multi-hyphenate and business leader. Simple Pleasures broke the ground, fertilized it deeply, and helped cultivate one of the most innovative and forward-looking careers ever accomplished by a five-string picker.

Now, some 34 years after its original release, that debut album has been reissued – on vinyl and digital, with a handful of digital-exclusive bonus tracks recovered from a cassette tape of demos. The project is a delightful time capsule and a perfect representation of the vast and varied musical ground Brown has covered over the intervening years. She may not have known it then – she readily admits, as a picker in her twenties, she was just taking this “banjo thing” day by day – but Simple Pleasures would lay the groundwork for all of her many successes in the music industry and in bluegrass.

For a special edition of First & Latest, we spoke to Alison Brown by phone about her first release and her latest – which just so happen to be the same album, the original and the new reissue. It’s essential listening for bluegrass, banjo, and roots music fans.

Simple Pleasures was originally released in 1990, 34 years ago. I wanted to start by asking you about your frame of mind now versus then, about what’s changed in the interim. What’s changed regarding how you view yourself as a creator and as a banjo player? Looking back, in retrospect, do you recognize the person you were then? What do you remember about your frame of mind when you first put the album out?

Alison Brown: It was this time in my life during which I was writing this music and then trying to get a record deal; I had just left my investment banking job and had taken this bizarre leap of faith, which I didn’t necessarily get a lot of support for. My parents weren’t saying, “Hey, I think you should quit your investment banking job to play banjo.” [Laughs] It really was a leap of faith.

I just couldn’t stop thinking about the banjo. So, I gave myself the challenge of seeing if I could write an album’s worth of music that would hold up and just try to make a record. And then, in the course of working on that, I wrote these tunes and joined Alison Krauss & Union Station. By the time we recorded the tunes, I’d been in her band for a year. I was really at the beginning of what has become my career path since then, but when I was doing it, I didn’t really know how it would be received or if it would get any props or even if it would be any good. All the validation that came on the heels of releasing this, and then everything since then, has made me a much more confident musician than I was when I wrote the music and recorded the record.

Before this album, were you already writing tunes? Was that something that you always did? Or was this an intentional practice shift for you? Was making an album of your own tunes something you had always been working towards or was it part of that purposeful transition from investment banking to banjo?

That is a really good question. I had never written much music up until that point, but I’d always wanted to. Stuart Duncan and I did a record called Pre-sequel. That was like a teen record, but we had a couple original tunes, stuff like “Possum Gravy on Grandma’s Beard” and “The Great Lasagna Rebellion.” It was like teen stuff.

Anyways, I really had wanted to challenge myself to see if I could write some “real music” – that isn’t really quite the right word, but some more substantial tunes and some tunes that really took the instrument maybe to a new place, which took my voice to a new place. That was a lot of this exercise and those 12 tunes. I didn’t know if I could write them or even if they would be any good, but that was like the beginning of this kind of process of self discovery.

When you look at the credits list – Mike Marshall and David Grisman and Alison Krauss and more – you can see some of the fingerprints of you and your community, but it was a kind of a longer process of you writing and getting to the point of recording, right?

I’m trying to remember… yeah, probably from the time I started writing the tunes was maybe middle of 1988 and then we recorded them beginning in 1990. So yeah, there was definitely some time in there–

Was there some extrapolating in your head of, “What are these songs going to sound like? Who is going to play them?” What do you remember about deciding on how you were going to make the tunes and who was going to make them with you? Because I have a feeling that was just as important a part of the process as having the material to record.

Once the door opened for me to work with David Grisman, to produce the record and play on it, then I was pretty much like, “What do you think, David?” But I knew I wanted to have Alison on the record and I knew I wanted to have Mike, ‘cause I love his music no matter what he’s playing. I’m the head of the “Mike Marshall Plays Guitar Fan Club.” [Laughs] I love his guitar playing. And Mike was in the Bay Area, so that made perfect sense.

But then, in terms of bringing in the flute or percussion, I hadn’t really thought about those things. When I listen to this record now, it’s surprising really how much of a footprint the record created for what we’re doing now. ‘Cause we’ve got a rhythm section and flute in the band. In some ways, it feels like after all this time we’ve come full circle, at least back to the seed that record planted, sonically, for the music.

That’s so interesting, to be able to look back and trace that throughline, when at that point it may have felt like a one-off to have those instruments and those styles represented in the music. And now it’s present through lots of your work.

Yeah, it is really interesting. There’s obviously things that weren’t included [on Simple Pleasures]. We’ve had piano in the band pretty much since the beginning and we didn’t have piano on that record, obviously. But I don’t know, somehow that doesn’t seem as much of a template thing, the idea of percussion elements and certainly the flute. David really brought that – and the idea of incorporating cello. I’m not sure I was really thinking about those things. My thinking was probably more in the bluegrass-rooted box.

One of the things that’s definitely changed from the original Simple Pleasures to the reissue over those 30-some years is these bonus tracks that you’ve added – such a time capsule. I wanted to ask you about their… I want to say provenance, but I don’t mean to be that formal. Like, how did you hold onto the demos over time, did you always have them in your back pocket?

You know, as we were working on re-master I kept thinking I knew I had a cassette of the demos. I just dug around and I found it! That’s where the actual takes came from, but that between-take talking, to me, is my favorite part of the whole thing. Just hearing Mike and David and Richard Greene, who produced those demos, talking to each other – I just think that’s the coolest thing. That came off the 2-inch tapes that we had. But the 2-inch tapes, we didn’t have the final mixes of the demos. So, it just worked out that we dumped the cassette tapes into this computer and tried to sweeten it a little bit and that’s what we used.

Looking back, this was a big transition point for you with a GRAMMY nomination, winning IBMA Banjo Player of the Year as the first woman to win an instrumental award. Of course this would end up a seminal album and was a really important kickstart for your incredible career. But at that point, back in 1990, were you worried about it? What was your frame of mind as far as expectations for what this album could do and where it could go?

I’m sure that I had no expectations. [Laughs] It was just something that I really wanted to do myself. I wanted to see, could I write a bunch of music and would it stick together? And, can I get some great people to play on it? I was just happy that all those things came together and I got it on a label.

It was just so cool to be on Vanguard Records. The Welk Music Group had bought that catalog and they had just started signing artists. I was one of the first artists they signed to the Vanguard imprint. All that was enough, but then to get a GRAMMY nomination was completely a surprise. I didn’t expect that at all, or the IBMA recognition. That validation was huge, obviously, and it would be for anybody, but for me it was just so huge. I actually took my parents with me to Radio City Music hall for the GRAMMYs and that went a long way toward them accepting my career 180. [Laughs]

It seems like this was definitely proof of concept for, “I can do this banjo thing. I can make banjo records. I can do this as a career.”

And in retrospect, I completely agree. In the moment, none of those things [were certain]. That’s what they say, “Hindsight’s 20/20.” And that’s so true; when you’re in the moment, you just don’t know how it’s going to turn out. Then it turned out great! I feel so lucky every day that I get to play music or create music or help somebody else create music, all that is just such a gift. Because it was not a foregone conclusion, I could easily have gone back to investment banking or something else with my tail between my legs. I’m just so grateful that isn’t the case.

At this point in your career, people think of you as a multi-hyphenate, as somebody who runs a label, is so active in the industry, and picks a really mean banjo. But this project predated Compass Records by several years. Were you already planning that sort of multi-prong, multi-hyphenate approach then? Or do you think it would be a surprise to 1990 Simple Pleasures Alison that you are the multi-hyphenate you are now?

Yeah no, I did not know it was [in my future], I think I was really just taking it a step at a time. At that particular point in time, my goal was just to write tunes and play in Alison [Krauss’] band. Then, when I left her band, I was really at this juncture again. My parents kept saying, “We really think you’d enjoy going to law school!” I was on the edge of applying to Vanderbilt Law School when I got a call from Michelle Shocked looking for a band leader for her world tour in 1992.

So no, I definitely didn’t have the multi-hyphenate, as you put it, plot hatched at all yet. That’s really something that came during that time that I spent with Michelle and then Garry West, who was playing bass in the band [with her as well]. We connected on a personal level, on a business level, and we started talking about “the good life.” Like, how do you make a life out of music? That’s when we started envisioning the different spokes of the wheel, and one of them was a record label and one of them was playing banjo and touring. That 1990s Alison was really just taking in a day at a time.

There’s this quality that musicians talk about a lot, almost to trope-ish levels, of not liking listening to themselves, not liking going back and hearing their own musical ideas or their own creativity from the past. It can be cringey! When you hear your young adult voice on the banjo now, what’s your reaction? Do you bristle at it? Do you feel inspired by it or do you have a moment where you’re like, “I can’t believe that I played that or I did that”? You’ve been inhabiting these tunes to remix and re-master them, not just rubber stamping a reissue. What does that feel like, to be going back and forth between who you are now and who you were then?

I really thought it was going to be like a lot of cringey stuff, like listening to those tracks and thinking, “Oh god, why did I play that?” Instead, I had a completely different feeling, because I felt like I could hear and really remember both the joy of figuring out that I could do this thing and the uncertainty of, “I don’t know if it’s any good or if it’s going to connect with anybody at all.” I can hear both of those things, but at the end of the day, what I felt most was just wishing I could reach back in time and give myself a pat on the back [and say,] “It’s going to work out okay and you’re on the right path.”

Because I think that’s the thing, we’re all looking for our true path. Sometimes it’s really hard to see, and for me, it was definitely hard to see. I really thought that I would be like a respectable business person and instead – well, I hope I’m a respectable business person, but it’s certainly not what I expected to be! [Laughs] I really thought, banker, lawyer, doctor, that kind of thing.

Your portfolio as a banjo player, label head, and producer is so diverse. And I wondered if you feel that’s directly correlated to being a woman who plays the banjo, or if you think there’s something else that’s driven that or informed that? Because I firmly believe marginalized folks in roots music – really anyone who’s not a straight white man – we often have to have very diverse career paths just to make a living, to make ends meet.

One thing I do notice is that big opportunities that opened up for me early on, they were all created for me by other women. That’s really not lost on me – whether it was Alison Krauss or Michelle Shocked. It wasn’t a male band leaders inviting me in. I think that’s really significant and that’s one of the things that I think is interesting about the times we’re in now, the fact that there’s much more diversity – even though it’s not as much as we would like to see. But there are women peppered throughout the ecosystem of the bluegrass community. We’re really in a position to empower and bring up the next generation, where we weren’t so much before. That makes it a really exciting time. I know that’s something that I love to look for opportunities to do.

If I’m producing a record, I want to bring those other voices into the room and let’s raise the next generation. ‘Cause when you come out of investment banking, you can see how adept the guys are at bringing on the next generation of guys, but women in corporate situations just historically haven’t [had the same access]. There are many reasons, it’s not their shortcoming. I think it’s just the circumstances, but now it doesn’t have to be that way. I find that particularly exciting.

34 years later, these folks who played on Simple Pleasures are still part of your community and are collaborators of yours. Back then, were you thinking, “All right, these are my ride or dies! We’re going to go the distance together.” Or was it like, “I can’t believe I get to be in a room with these folks and I hope we can do it again”? How does it feel now to look back and have decades-long relationships with these folks that you made the album with and to have that community be such a present part of the music that you continue to make and the records that you put out?

It’s amazing to look back and to think about the fact that I’ve known Mike Marshall since, gosh, I think I was a teenager the first time I met Mike? To have 50-year-long relationships with some of these people, it’s an amazing thing and it’s such a gift. I think one of the best things about our community is that people can have careers that extend over decades and you can have friendships with people that extend over half a century or more. I’ve known Stuart Duncan since he was 10, so I’ve known him for half a century. It’s crazy and wonderful too. And it’s such an amazing aspect of our community.

I don’t know if it’s the same in other kinds of music, but I think the intergenerational aspect of bluegrass music and roots music just creates for some amazing lifelong friendships. I think it’s not uncommon for people to start when they’re 10 years old – or, Stuart started playing this music when he was six or seven. When I met him when he was 10, he was already a hotshot fiddle player. The fact that you can get into this music as such a youngster, keep playing it, and there’s room for you even when every hair on your head is gray, it’s just a great thing. I think in popular music the window is more narrow.

But in this music, people want to see you play your music whether you’re six or whatever age. How old was Bobby Osborne? He was 92! The record that I did with Bobby, Original, we was 86/87-years-old when we recorded that record. You wouldn’t see an 87-year-old pop artist probably making a record.