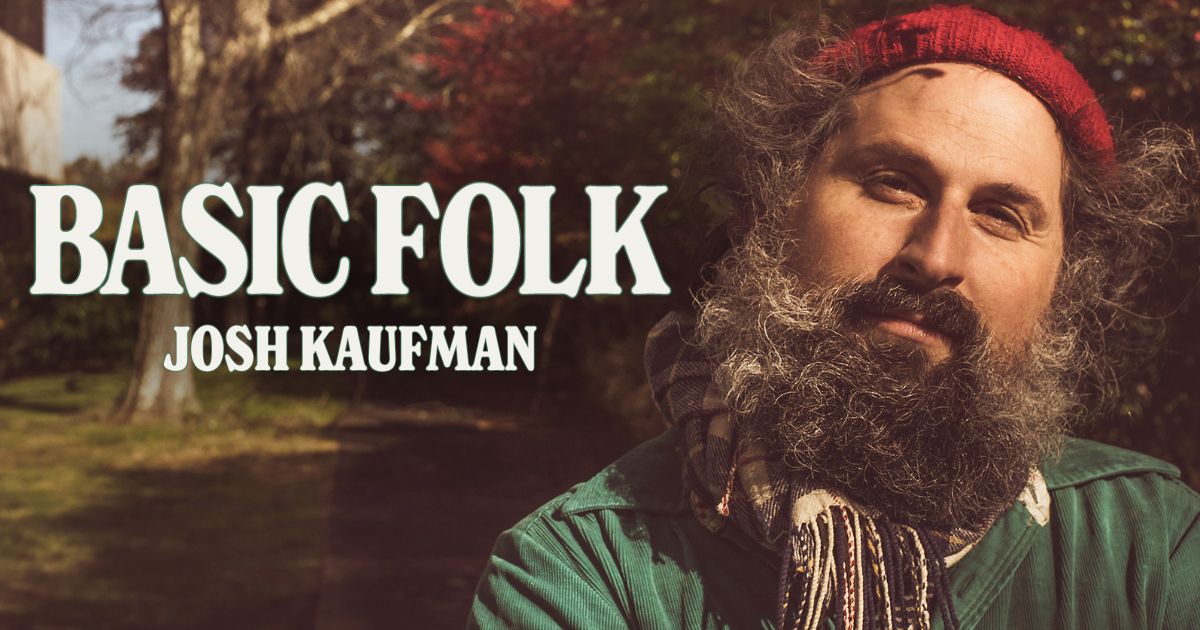

Caroline Spence knows better than anyone the importance of community in the roots music scene. Since her 2015 debut album, Somehow, the singer-songwriter has risen through the ranks with four additional solo albums including her latest, Heart Go Wild. Stylistically, Spence fits within the realm of Natalie Hemby, Aoife O’Donovan, Lori McKenna, and Mary Bragg, with a smattering of Mary Chapin Carpenter sensibility. She has garnered praise from both direct peers and industry giants alike. From signal-boosting her work online to recording her songs, many musicians and artists have used their platforms to give Spence a well-deserved spotlight.

Throughout the past decade, Spence has used these moments to nurture friendships within a thankless industry. “The acknowledgement and validation from artists that I respect have been vital in keeping the fire burning under me when parts of the industry have threatened to put it out,” Spence tells BGS.

“No ‘suit’ can convince me I’m not good enough when I have worked with my heroes and have the respect of artists I admire.”

Reciprocated applause and mutual admiration prove essential to building relationships, in addition to contextualizing an artist’s music within the scene for those fans who may not be familiar. For example, Miranda Lambert has enlisted countless lesser-known artists for her tours, including Gwen Sebastian, Ashley Monroe, and Angaleena Presley. These placements introduce her loyal audience to talent they might not have discovered elsewhere, thus giving those artists more name recognition.

Even more importantly, Spence finds these shout-outs and promotional spots to be her “life force” in keeping her inspired to push through trying times. “My primary goal has always been to be good at my craft and to get better at it,” she says. “To me, the most important judges of that are those who are masters of theirs, and it’s been deeply meaningful every time someone I admire has paid attention to, let alone praised, what it is that I do.”

In her career, Spence has tumbled into the orbits of countless artists who have shown unwavering support for her work. A big Hayes Carll fan, she covered his song “It’s a Shame,” from his 2002 album, Flowers & Liquor, early in her career and later toured with him in 2021 – a moment Spence describes as coming “full circle.” She’s also toured with John Moreland and Madi Diaz. In addition, she wrote “Heavy” with Carl Anderson for Andrew Combs’ album Worried Man and another song she wrote, “We Don’t Know We’re Living,” was recorded by Lucie Silvas, Brandi Carlile, and Joy Oladokun. “[Brandi] called it ‘a once in a century song,’” notes Spence.

Despite not having a “game-changing platform,” as she puts it, she pays it forward by sharing “the work of my peers and what I am loving listening to. I think word-of-mouth from trusted personal sources is still the best way to get someone to pay attention to music.”

She takes a moment to shout out others, beginning with Ken Yates & Brian Dunne before mentioning several other artists she’s been listening to, including Angela Autumn (“Her song ‘Electric Lizard’ is intoxicating and reminds me of some of the tracks that made me fall in love with music in high school,” she says), Brennan Wedl & Mariel Buckley, and Danny Malone, “an incredible songwriter out of Austin that I recently saw at a house show in Nashville and was absolutely floored by.”

In our conversation, Spence names an additional six artists, from Miranda Lambert to Tyler Childers, who have uplifted her music over the years.

The National

“The fact that I have a duet with Matt Berninger is still completely insane to me. When I was in college in Ohio, falling in love with The National, I could have never even dreamed that I would cross paths with Matt, let alone have him sing words I wrote. I love that band, and his voice is legendary. It still feels unreal.”

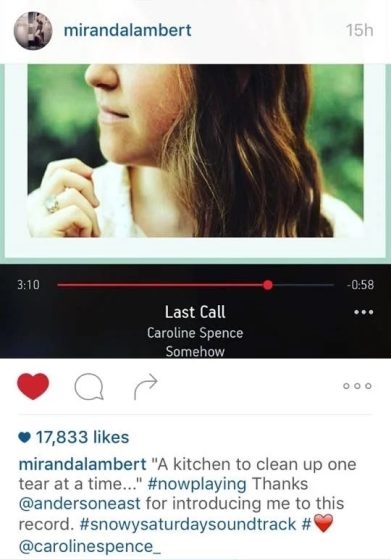

Miranda Lambert

“[She] posted about my first record back in 2016, and that totally blew my mind. I had just been in the studio making my second record [Spades and Roses] and was questioning a lot, and that really felt like a sign to keep doing what I was doing. Part of my dream when I moved to Nashville was to write songs for her, so that was an incredibly validating moment.”

Lori McKenna

“Lori added my music to her monthly favorites playlists that she makes. She featured on a song we wrote together called ‘The Next Good Time.’ One of my biggest heroes and one of the people who inspired me to start pursuing this work.”

For our Artist of the Month feature, Spence joined McKenna for an intimate and engaging conversation. Read here.

Clare Bowen

“Clare recorded my song ‘All The Beds I’ve Made’ on her self-titled album.”

Tyler Childers

“I’ve known him since 2014 and he opened for me in early 2016 – a month after Miranda posted about my record, and she actually came to the show. I toured opening for him in 2017 and 2019. At some point, he posted about my album on his IG.”

Mary Chapin Carpenter

“We connected on social media and she eventually invited me to open some shows for her. A treasured memory was performing in the round with her at the Edmonton Folk Festival and her asking me to play ‘I Know You Know Me’ and her singing it with me.”

View this post on Instagram

Continue exploring our Artist of the Month coverage of Caroline Spence here.

Photo Credit: Caroline Walker Evans

Inset images and screenshot courtesy of Caroline Spence.