Last night, the International Bluegrass Music Association announced the winners of their 35th Annual Bluegrass Music Awards in Raleigh, North Carolina, the final awards show held in Raleigh before IBMA’s move to Chattanooga, Tennessee next year. The star-studded, three-hour awards show was hosted by bassists John Cowan and Missy Raines and featured performances by many nominees and featured special guests and collaborations.

Billy Strings, Sister Sadie, Authentic Unlimited, and Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway lead the nominations going into the evening. Authentic Unlimited walked away with the most trophies, with the group as a whole landing three awards – including a tie for Music Video of the Year with Special Consensus. Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway took home the honor for Album of the Year, while Billy Strings’ sole win of the night was for his feature on Tony Trischka’s collaborative Earl Jam track, “Brown’s Ferry Blues.”

Also honored during the event were this year’s Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductees. Entered into the Hall of Fame – the highest honor awarded by IBMA and its membership – were Jerry Douglas, Katy Daley, and Alan Munde.

Find the full list of winners and recipients of this year’s IBMA Awards below. Congratulations to all of the nominees, bands, artists, labels, and industry stakeholders represented at this year’s awards.

ENTERTAINER OF THE YEAR

Billy Strings

Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway

Del McCoury Band

Sister Sadie

The Po’ Ramblin’ Boys

VOCAL GROUP OF THE YEAR

Authentic Unlimited

Sister Sadie

Blue Highway

Del McCoury Band

Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway

INSTRUMENTAL GROUP OF THE YEAR

Billy Strings

Michael Cleveland & Flamekeeper

Travelin’ McCourys

East Nash Grass

Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway

SONG OF THE YEAR

“Fall in Tennessee” – Authentic Unlimited

Songwriters: John Meador/Bob Minner

Producer: Authentic Unlimited

Label: Billy Blue Records

“Willow” – Sister Sadie

Songwriter: Ashley McBryde

Producer: Sister Sadie

Label: Mountain Home

“Too Lonely, Way Too Long” – Rick Faris with Del McCoury

Songwriter: Rick Faris

Producer: Stephen Mougin

Label: Dark Shadow Recording

“Forever Young” – Daniel Grindstaff with Paul Brewster & Dolly Parton

Songwriters: Jim Cregan/Kevin Savigar/Bob Dylan/Rod Stewart

Producer: Daniel Grindstaff

Label: Bonfire Music Group

“Kentucky Gold” – Dale Ann Bradley with Sam Bush

Songwriters: Wayne Carson/Ronnie Reno

Producer: Dale Ann Bradley

Label: Pinecastle

ALBUM OF THE YEAR

City of Gold – Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway

Producers: Jerry Douglas/Molly Tuttle

Label: Nonesuch

Last Chance to Win – East Nash Grass

Producer: East Nash Grass

Label: Mountain Fever

Jubilation – Appalachian Road Show

Producer: Appalachian Road Show

Label: Billy Blue Records

No Fear – Sister Sadie

Producer: Sister Sadie

Label: Mountain Home

So Much for Forever – Authentic Unlimited

Producer: Authentic Unlimited

Label: Billy Blue Records

GOSPEL RECORDING OF THE YEAR

“When I Get There” – Russell Moore & IIIrd Tyme Out

Songwriter: Michael Feagan

Producer: Russell Moore & IIIrd Tyme Out

Label: Independent

“Thank You Lord for Grace” – Authentic Unlimited

Songwriter: Jerry Cole

Producer: Authentic Unlimited

Label: Billy Blue Records

“Just Beyond” – Barry Abernathy with John Meador, Tim Raybon, Bradley Walker

Songwriters: Rick Lang/Mike Richards/Windi Robinson

Producer: Jerry Salley

Label: Billy Blue Records

“God Already Has” – Dale Ann Bradley

Songwriter: Mark “Brink” Brinkman/David Stewart

Producer: Dale Ann Bradley

Label: Pinecastle

“Memories of Home” – Authentic Unlimited

Songwriter: Jerry Cole

Producer: Authentic Unlimited

Label: Billy Blue Records

INSTRUMENTAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR

“Rhapsody in Blue(grass)” – Béla Fleck

Songwriter: George Gershwin arr. Ferde Grofé/Béla Fleck

Producer: Béla Fleck

Label: Béla Fleck Productions/Thirty Tigers

“Knee Deep in Bluegrass” – Ashby Frank

Songwriter: Terry Baucom

Producer: Ashby Frank

Label: Mountain Home

“Panhandle Country” – Missy Raines & Allegheny

Songwriter: Bill Monroe

Producer: Alison Brown

Label: Compass Records

“Lloyd’s of Lubbock” – Alan Munde

Songwriter: Alan Munde

Producer: Billy Bright

Label: Patuxent

“Behind the 8 Ball” – Andy Leftwich

Songwriter: Andy Leftwich

Producer: Andy Leftwich

Label: Mountain Home

NEW ARTIST OF THE YEAR

East Nash Grass

Bronwyn Keith-Hynes

AJ Lee & Blue Summit

Wyatt Ellis

The Kody Norris Show

COLLABORATIVE RECORDING OF THE YEAR

“Brown’s Ferry Blues” – Tony Trischka featuring Billy Strings

Songwriters: Alton Delmore/Rabon Delmore

Producer: Béla Fleck

Label: Down the Road

“Fall in Tennessee” – Authentic Unlimited with Jerry Douglas

Songwriters: John Meador/Bob Minner

Producer: Authentic Unlimited

Label: Billy Blue Records

“Forever Young” – Daniel Grindstaff with Paul Brewster, Dolly Parton

Songwriters: Jim Cregan/Kevin Savigar/Bob Dylan/Rod Stewart

Producer: Daniel Grindstaff

Label: Bonfire Music Group

“Bluegrass Radio” – Alison Brown and Steve Martin

Songwriters: Steve Martin/Alison Brown

Producers: Alison Brown/Garry West

Label: Compass Records

“Too Old to Die Young” – Bobby Osborne and CJ Lewandowski

Songwriters: Scott Dooley/John Hadley/Kevin Welch

Producer: CJ Lewandowski

Label: Turnberry Records

MALE VOCALIST OF THE YEAR

Dan Tyminski

Greg Blake

Del McCoury

Danny Paisley

Russell Moore

FEMALE VOCALIST OF THE YEAR

Molly Tuttle

Jaelee Roberts

Dale Ann Bradley

AJ Lee

Rhonda Vincent

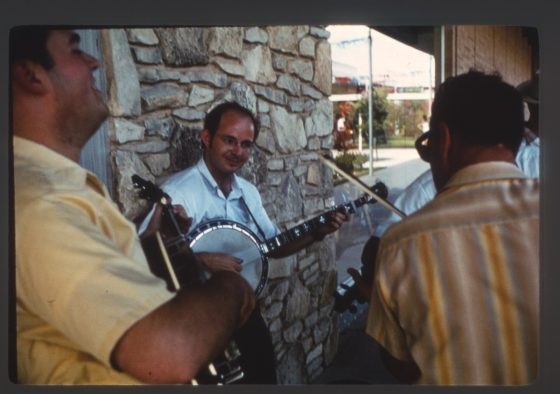

BANJO PLAYER OF THE YEAR

Kristin Scott Benson

Gena Britt

Alison Brown

Béla Fleck

Rob McCoury

BASS PLAYER OF THE YEAR

Missy Raines

Mike Bub

Vickie Vaughn

Todd Phillips

Mark Schatz

FIDDLE PLAYER OF THE YEAR

Jason Carter

Bronwyn Keith-Hynes

Michael Cleveland

Stuart Duncan

Deanie Richardson

RESOPHONIC GUITAR PLAYER OF THE YEAR

Justin Moses

Rob Ickes

Jerry Douglas

Andy Hall

Gaven Largent

GUITAR PLAYER OF THE YEAR

Billy Strings

Molly Tuttle

Trey Hensley

Bryan Sutton

Cody Kilby

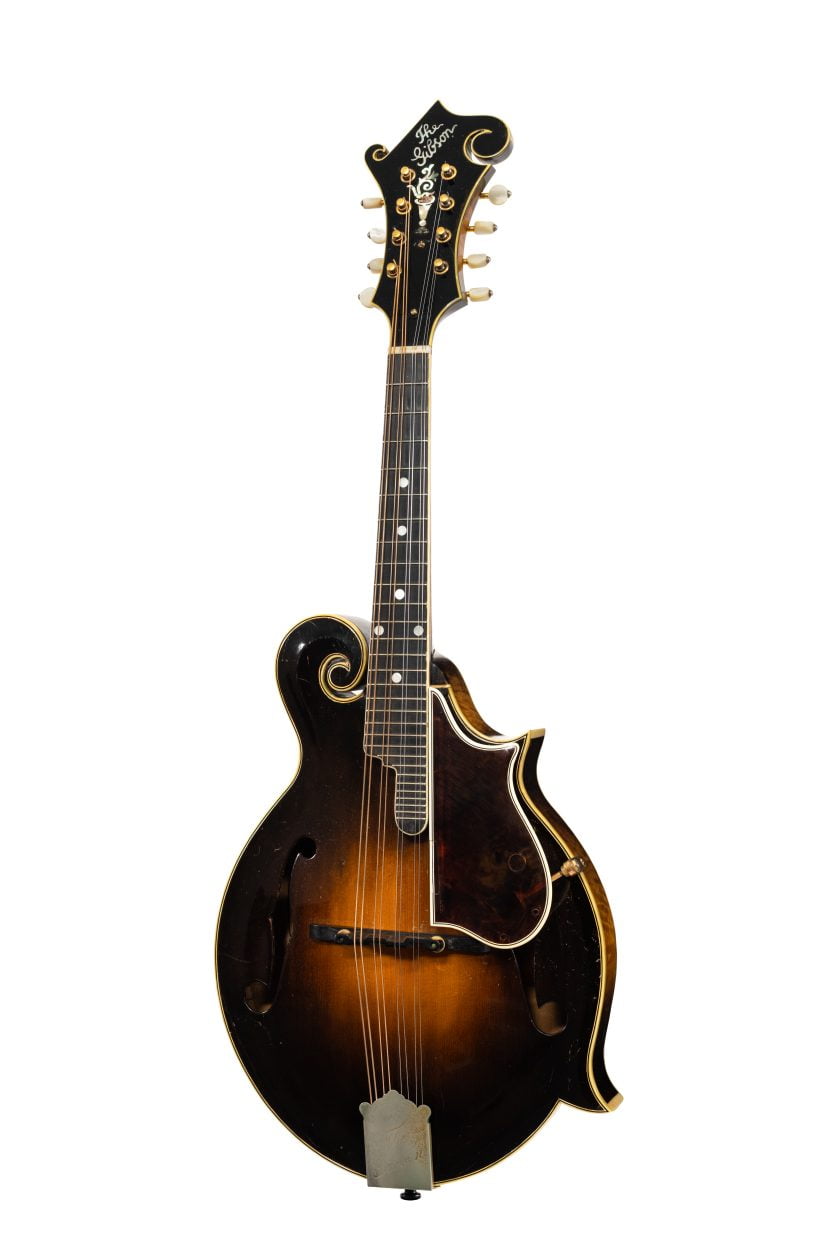

MANDOLIN PLAYER OF THE YEAR

Sierra Hull

Sam Bush

Ronnie McCoury

Jesse Brock

Alan Bibey

MUSIC VIDEO OF THE YEAR

“Willow” – Sister Sadie

Label: Mountain Home

“Fall in Tennessee” – Authentic Unlimited

Label: Billy Blue Records (TIE)

“The City of New Orleans” – Rhonda Vincent & The Rage

Label: Upper Management Music

“I Call Her Sunshine” – The Kody Norris Show

Label: Rebel Records

“Alberta Bound” – Special Consensus with Ray Legere, John Reischman, Patrick Sauber, Trisha Gagnon, Pharis & Jason Romero, and Claire Lynch

Label: Compass Records (TIE)

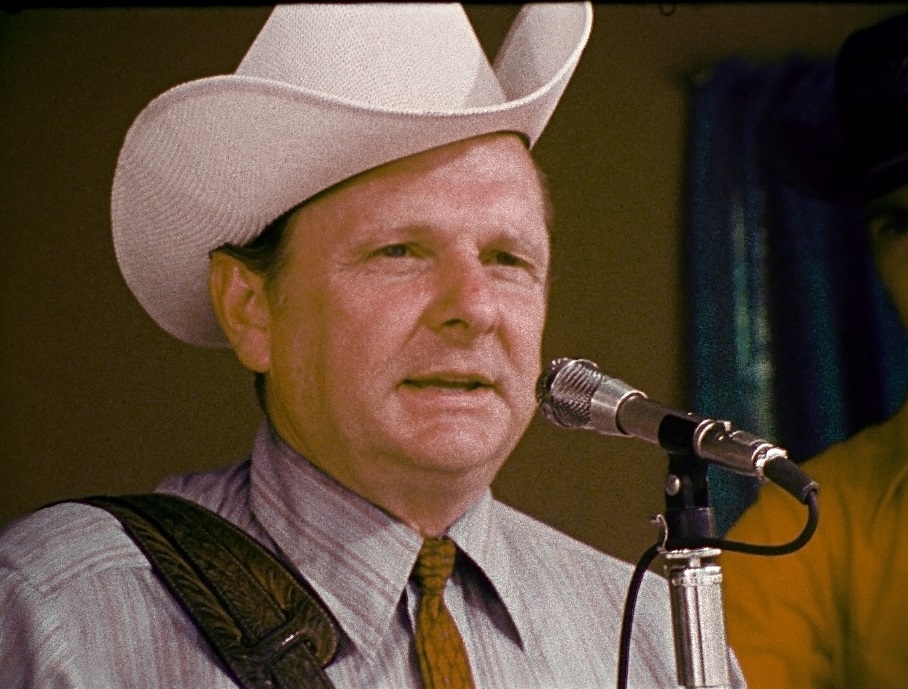

BLUEGRASS MUSIC HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES

Alan Munde

Jerry Douglas

Katy Daley

DISTINGUISHED ACHIEVEMENT AWARD RECIPIENTS

Cindy Baucom

Laurie Lewis

Richard Hurst

ArtistWorks

Bloomin’ Bluegrass Festival

Photo Credit: Authentic Unlimited with special guest Jerry Douglas perform at the IBMA Awards show. Shot by Dan Schram.